I’m not black, I’m Michael Jordan What is the measure of Jordan's impact on black culture?

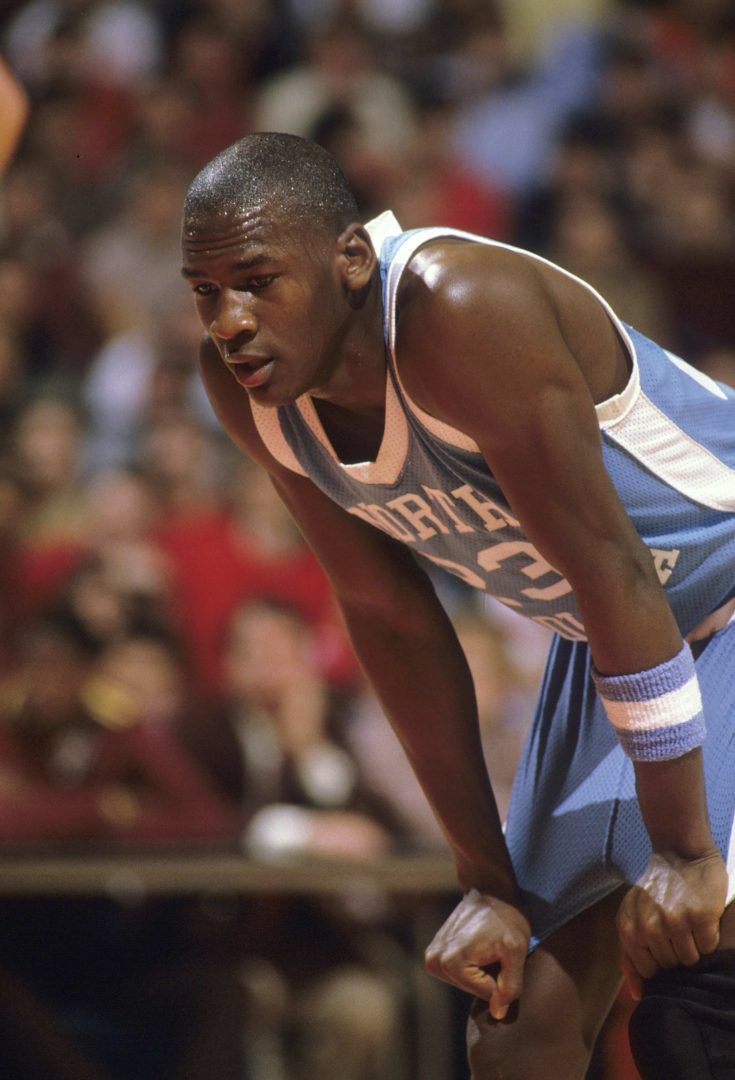

In a passage in his biography Michael Jordan, The life Roland Lazenby talking about Jordan's childhood, reports one of his own words: "I considered myself a racist at the time. I was against all kinds of white people." Michael Jordan had found himself in the position where every black citizen in the south of the United States found himself at least once in his life, and had felt on his own skin what racism of the 1970s meant. Jordan was also born in Wilmington, North Carolina, at a time when the new Ku Klux Klan was home to the state, which was reforming at the time. It seems there have been more than 1,000 clan members in North Carolina, more than in all the other Southern states put together.

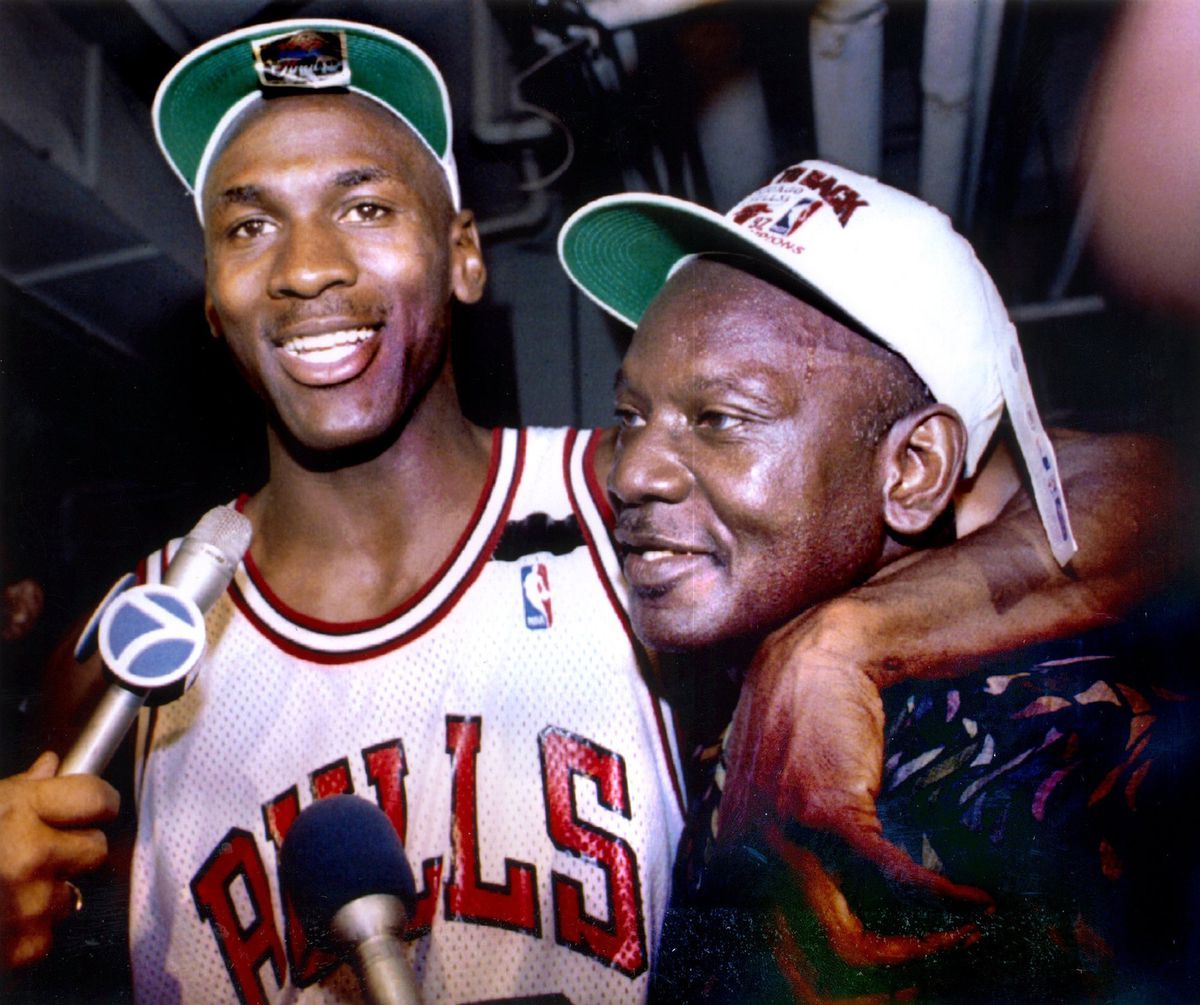

Lazenby's biography, essential for those who really want to know Michael Jordan, is an important document because it testifies to some of the rare moments when we hear about Michael Jordan publicly in relation to the concept of race. There aren't many public moments when the political intersection between Michael Jordan and black culture has been very clear: the unhappy and famous "Republicans buys sneakers, too," attributed to Jordan when he called for support from Harvey Gantt (black Democratic politician) in the North Carolina Senate campaign against Jesse Helms (Republican); The public statement made in 2016, when in a letter published in The Undefeated, Jordan wrote: «As a proud American, a father who lost his own dad in a senseless act of violence, and a black man, I have been deeply troubled by the deaths of African-Americans at the hands of law enforcement and angered by the cowardly and hateful targeting and killing of police officers». For many, even those statements were not enough, Michael Jordan's social interest was never enough.

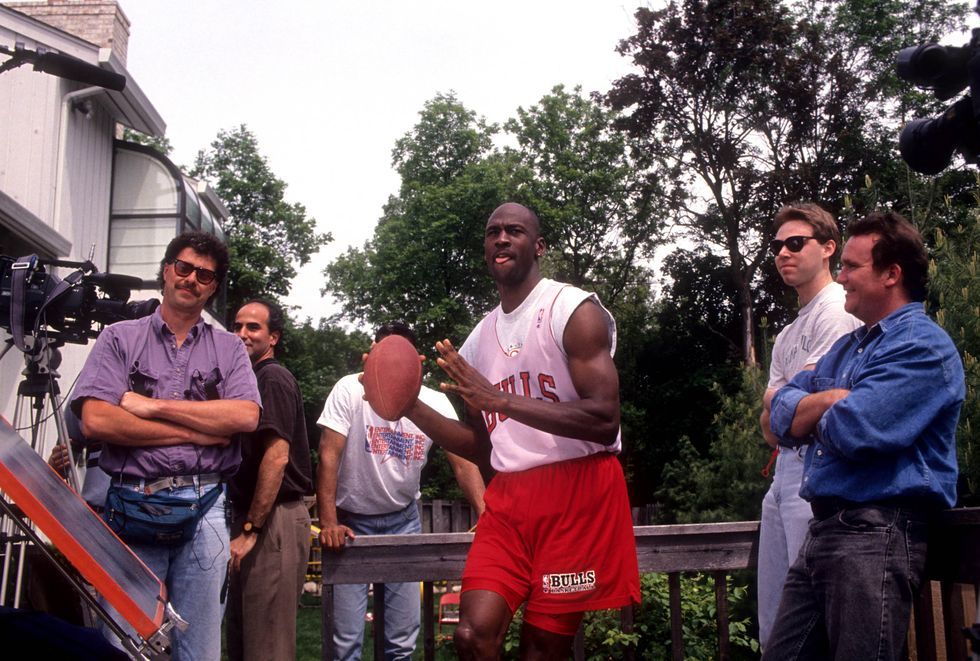

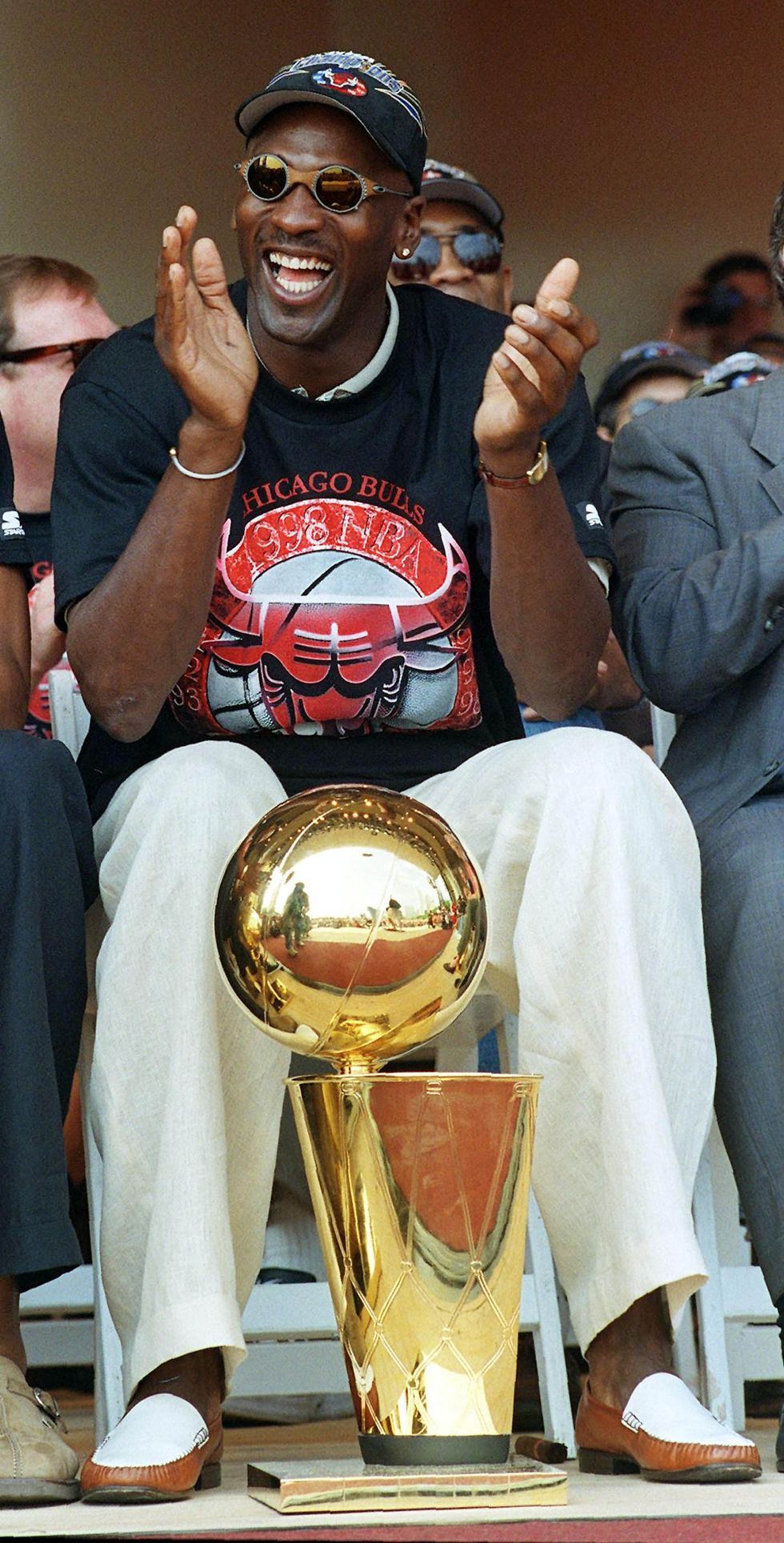

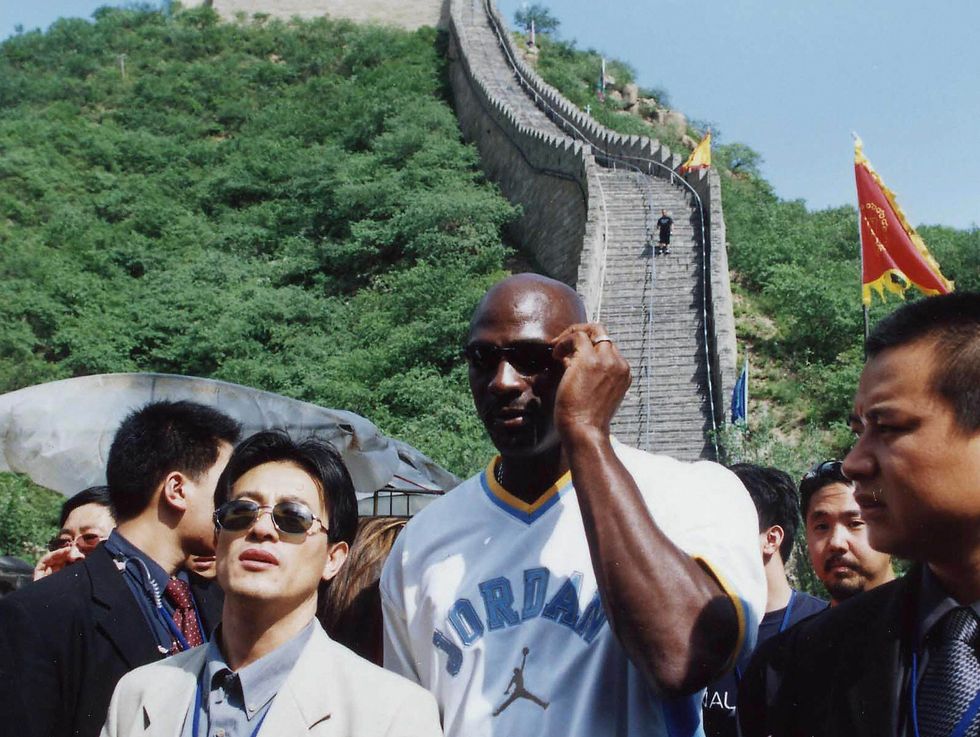

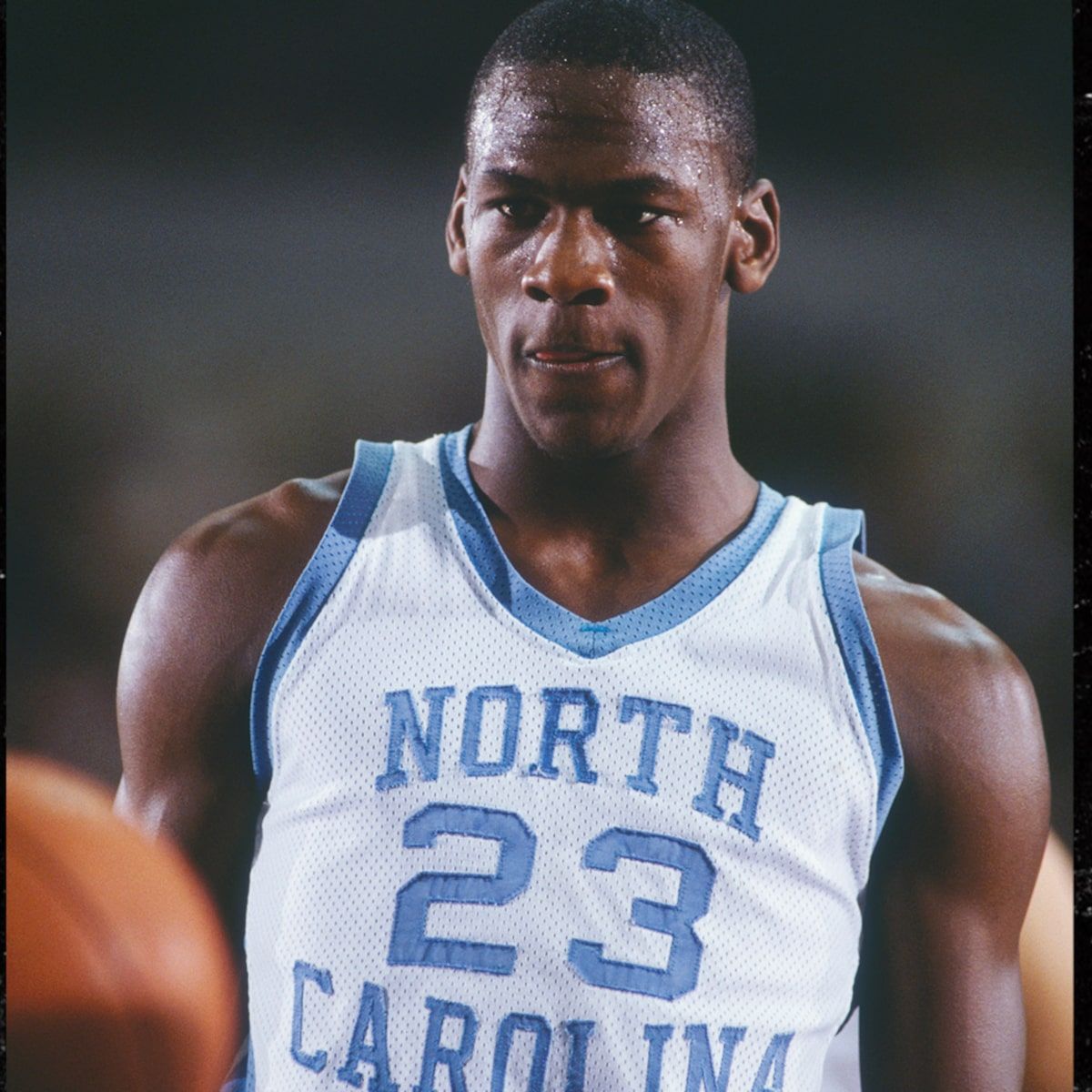

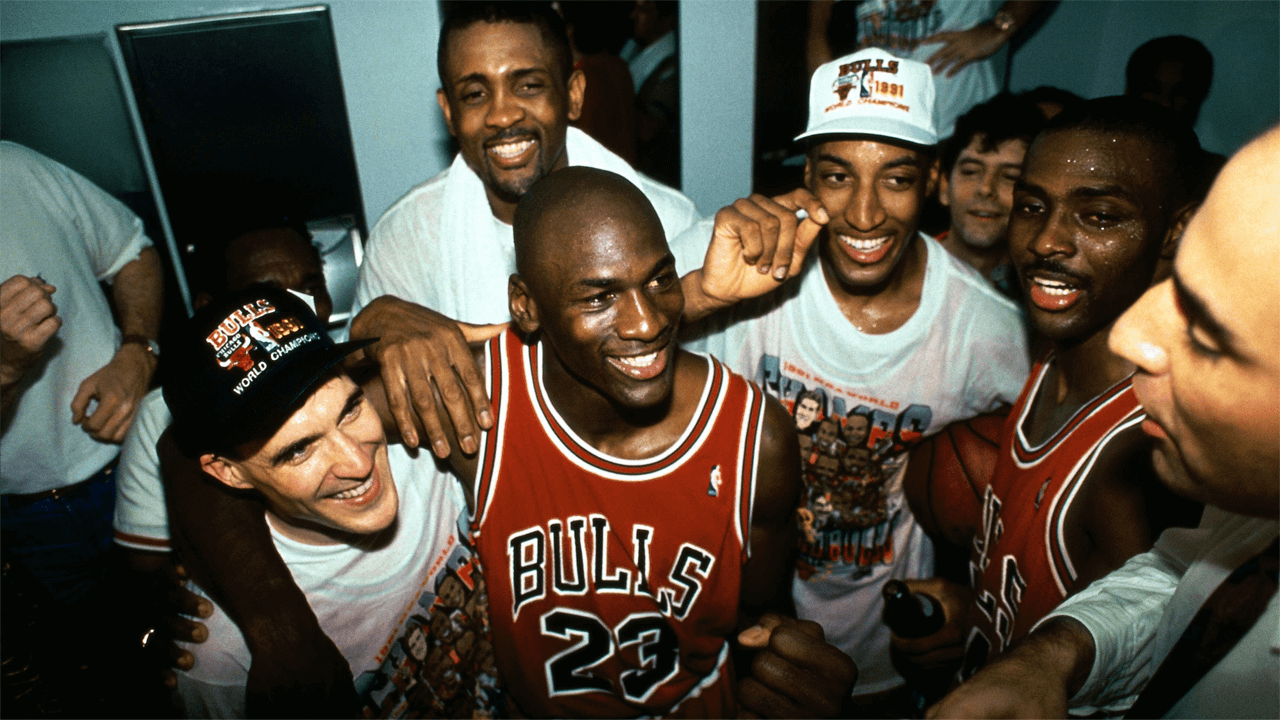

Among the many things that The Last Dance - the ESPN documentary that chronicles the season of the last ring of the Chicago Bulls - manages to tell, some in an extremely partisan way, others in a more balanced way, has the great merit of remembering today how Michael Jordan was in fact the most famous person in the world. It's a difficult concept to digest in 2020, in the age of impromptu glory and widespread celebrity, but Michael Jordan was literally the most popular man in the world. And he was black. Myles Brown, in a piece on GQ, wrote: «It's important to seriously consider, for a moment, the space Michael Jordan occupied. The most famous man in the world was black. He represented an entire race and his country too. Every dunk was for the red, white, and blue. Any misstep would ensure no one else who looked like him was ever afforded the opportunity to fuck such a good thing up again.».

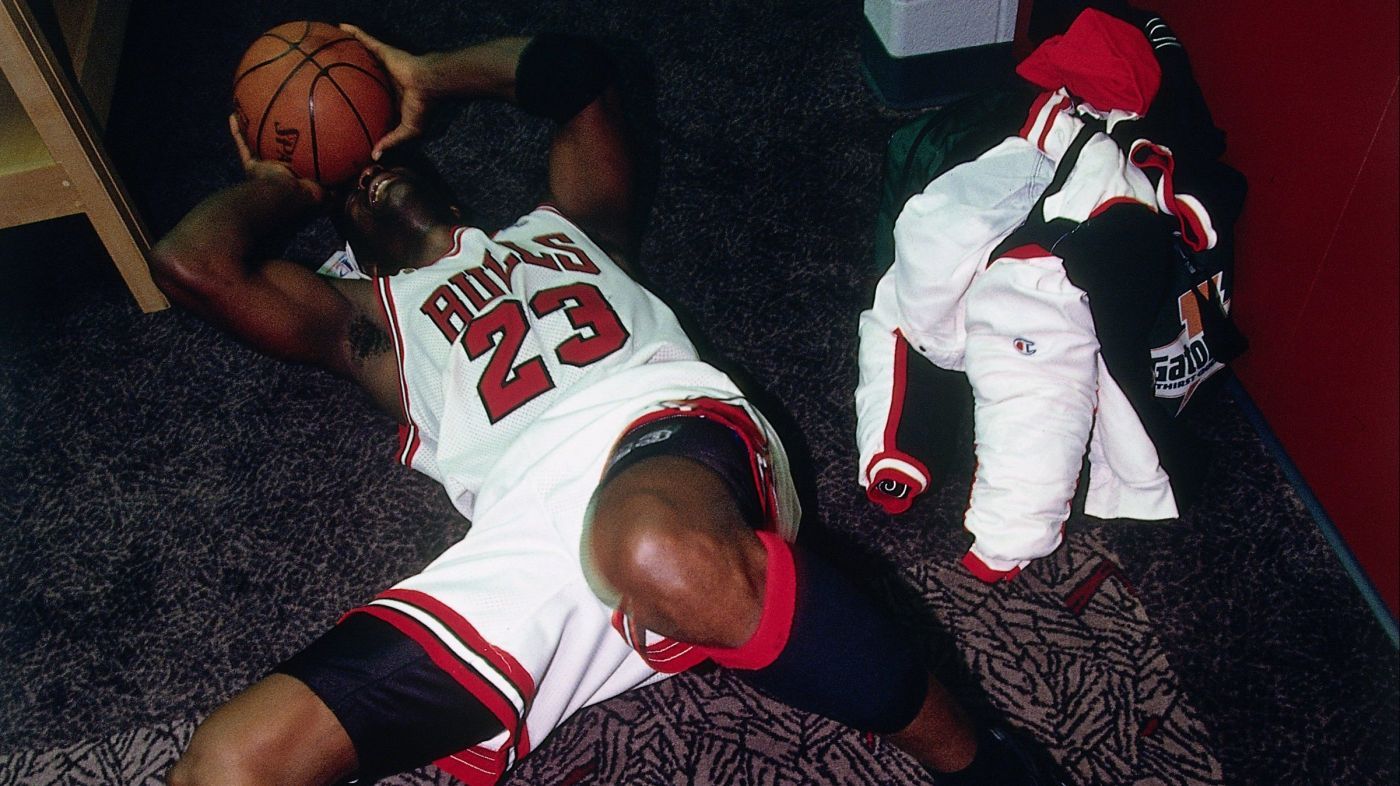

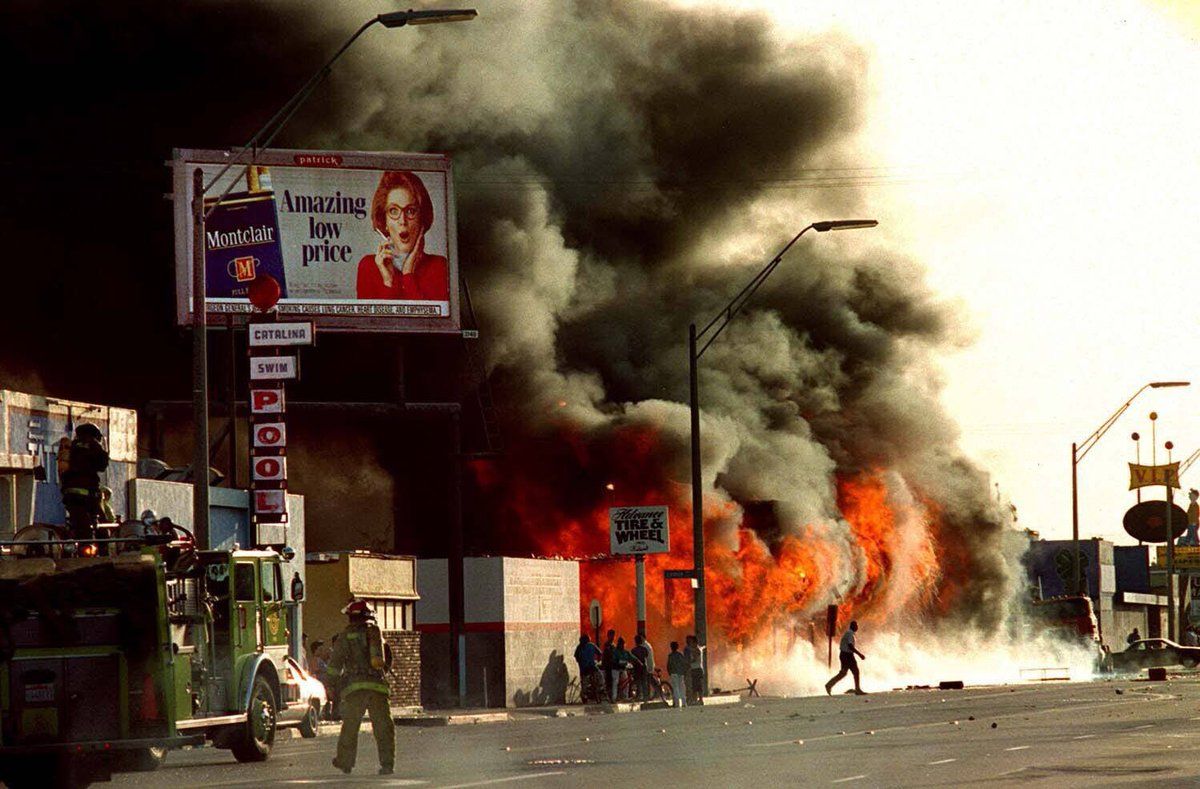

That space, however, that position of incredible domination, came at a price, a price that perhaps did not seem even so high to pay: Michael has practically removed from his public behavior all kinds of racial connotations, coming to be in the eyes of the world the example of the perfect American athlete. In some ways, Michael Jordan was the first example of an individual in a post-racial society, at a time when, however, the rest of the United States was living a different reality. When Los Angeles was knocked out in 1992 by the riots that followed the acquittal of the four LAPD officers for the beating of Rodney King, Michael Jordan was already an NBA champion, preparing to lead the Dream Team to the Olympics. Craig Hodges, the Bulls guard on the first ring, once said he asked Jordan to boycott Game 1 of the Finals against the Lakers, getting a no in response from MJ: "He didn't speak primarily because he didn't know what to say - not because he was a bad person," Hodges said. A theory also confirmed by Jordan himself, during an interview with Craig Melvin in 2019: «When I was playing, my vision – my tunnel vision – was my craft. I was a professional basketball player and tried to do that the best I could. Now I have more time to understand things around me, understand causes, understand issues and commit my voice, my financial support to».

Michael Jordan was too busy becoming the best basketball player in the world, and in doing so regardless of his race, he required the freedom to do so. A white freedom.

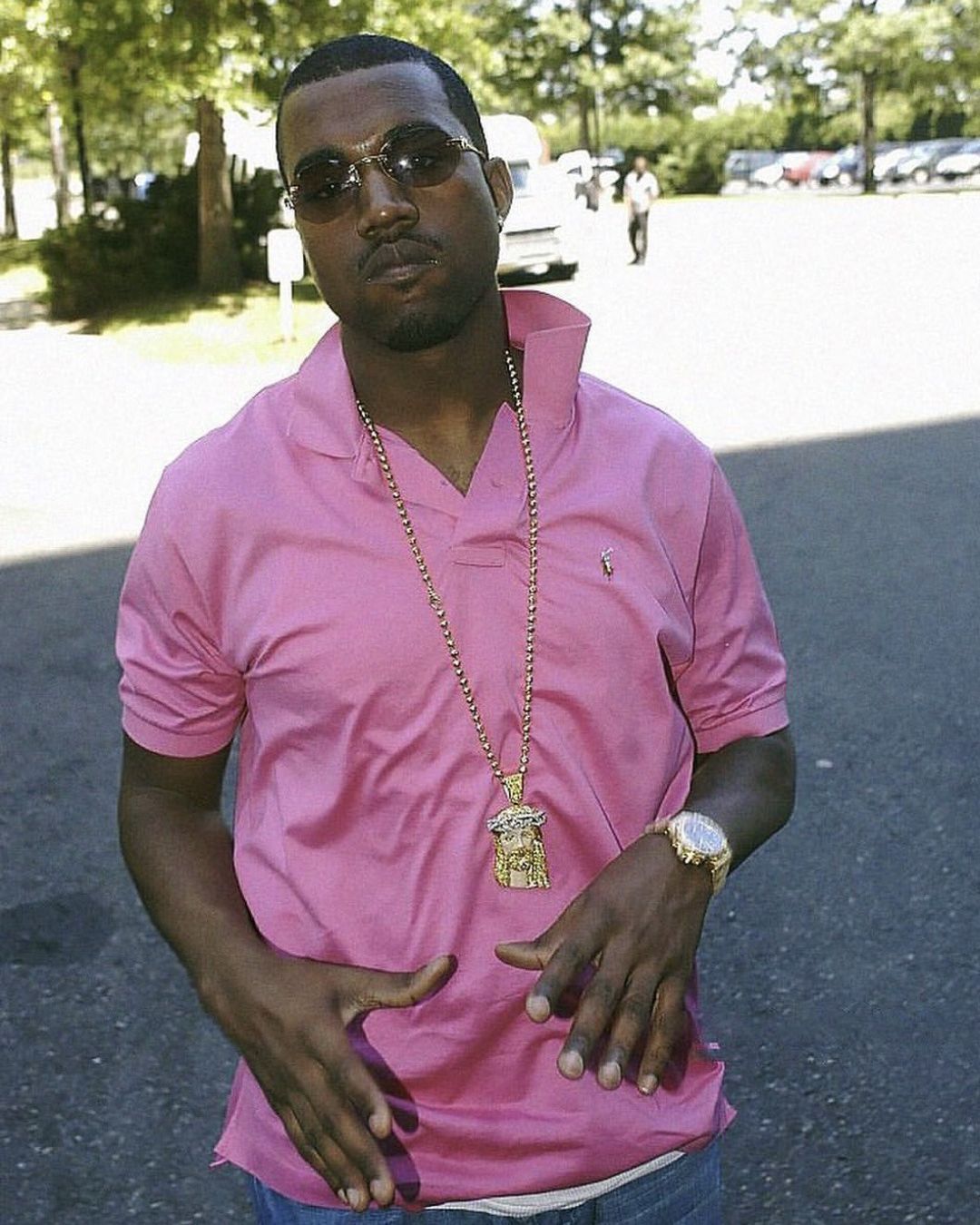

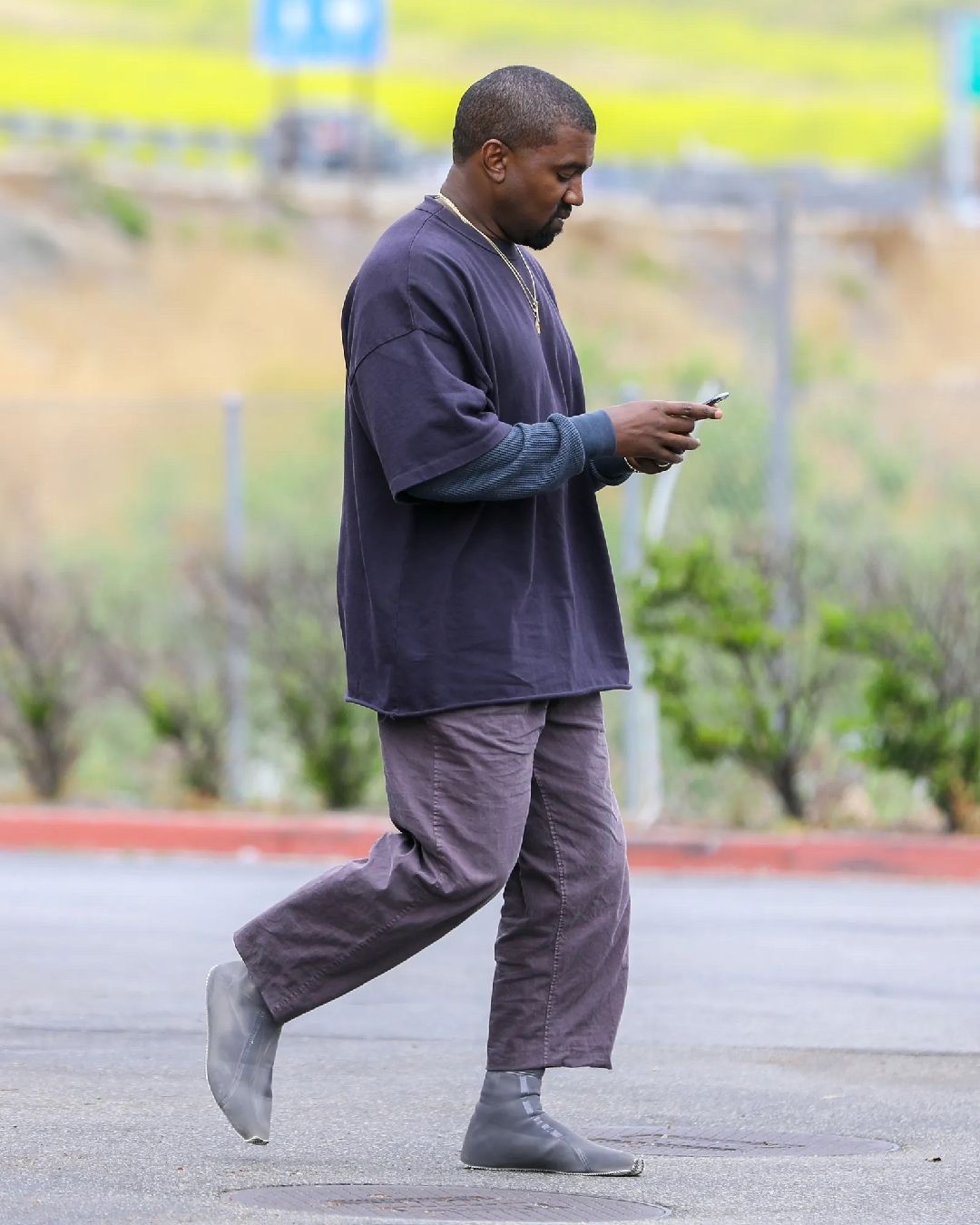

In his essay "I'm not black, I'm Kanye" - from which this piece takes all the inspiration - writer Ta-Nehisi Coates describes Kanye West's position in the months following his rapprochement with Donald Trump, embarrassing statements about slavery as a choice and the use of the MAGA hat, moments that have been met with fierce criticism of Kanye's actions and persona:

«West calls his struggle the right to be a “free thinker,” and he is, indeed, championing a kind of freedom—a white freedom, freedom without consequence, freedom without criticism, freedom to be proud and ignorant; freedom to profit off a people in one moment and abandon them in the next;[...] a conqueror’s freedom [...], the freedom of suburbs drawn with red lines, the white freedom of Calabasas.».

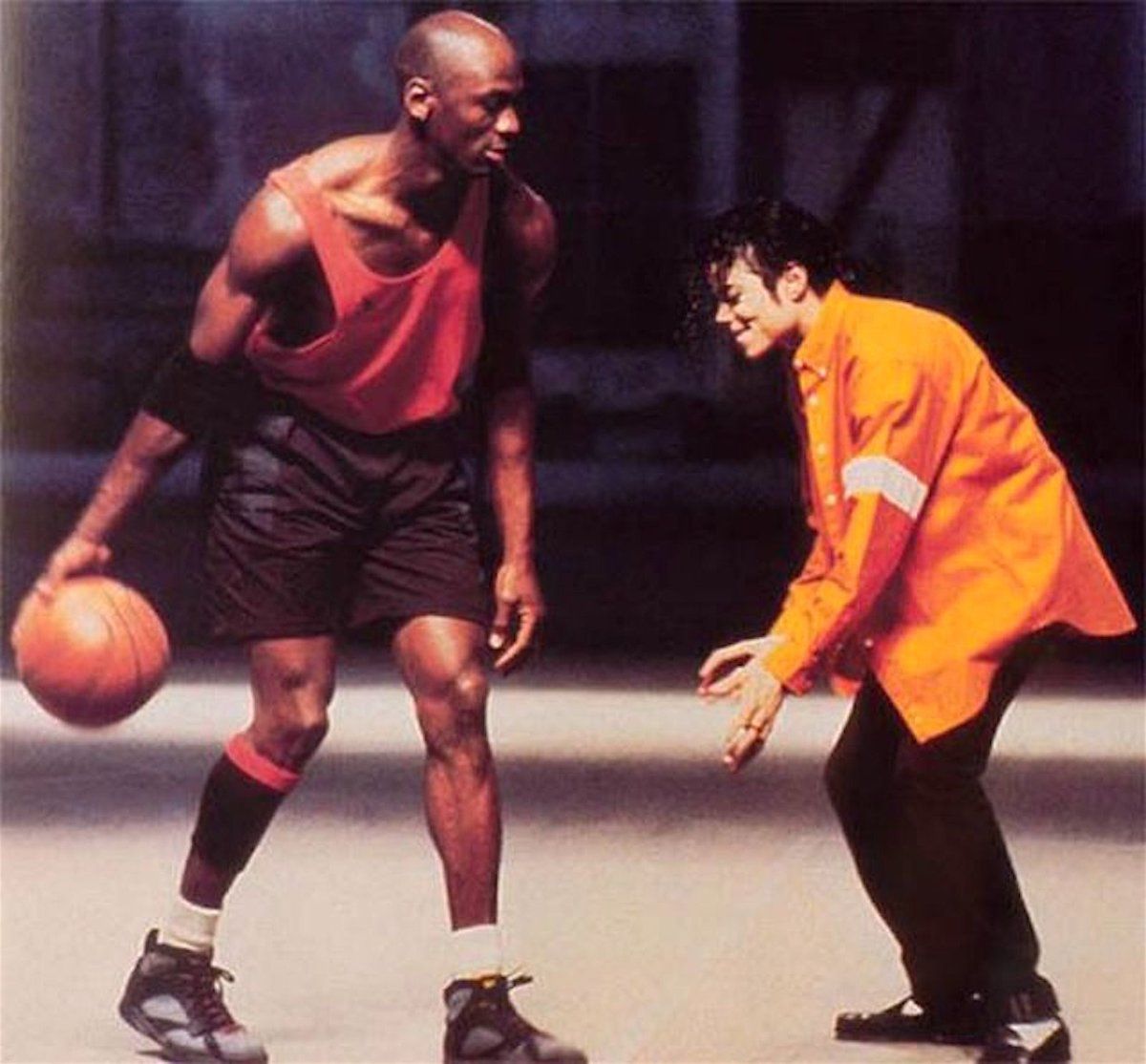

In describing the concept of white freedom, Coates repeatedly quotes Michael Jackson, another American child prodigy, who is the best possible example of pursuing - perhaps even physical - "white freedom." The points of contact between the two don't just stop at the initials, MJ, as it might actually be amazing that the two most popular people in the world had the same initials. Marcus Mabry writes in The New York Times:«Mr. Jackson was to music what Michael Jordan was to sport and Barack Obama for politics: a towering figure with cross appeal, though, when he was still alive, some black fans of Mr. Jackson wondered if he was proud of them when they were proud of him.».

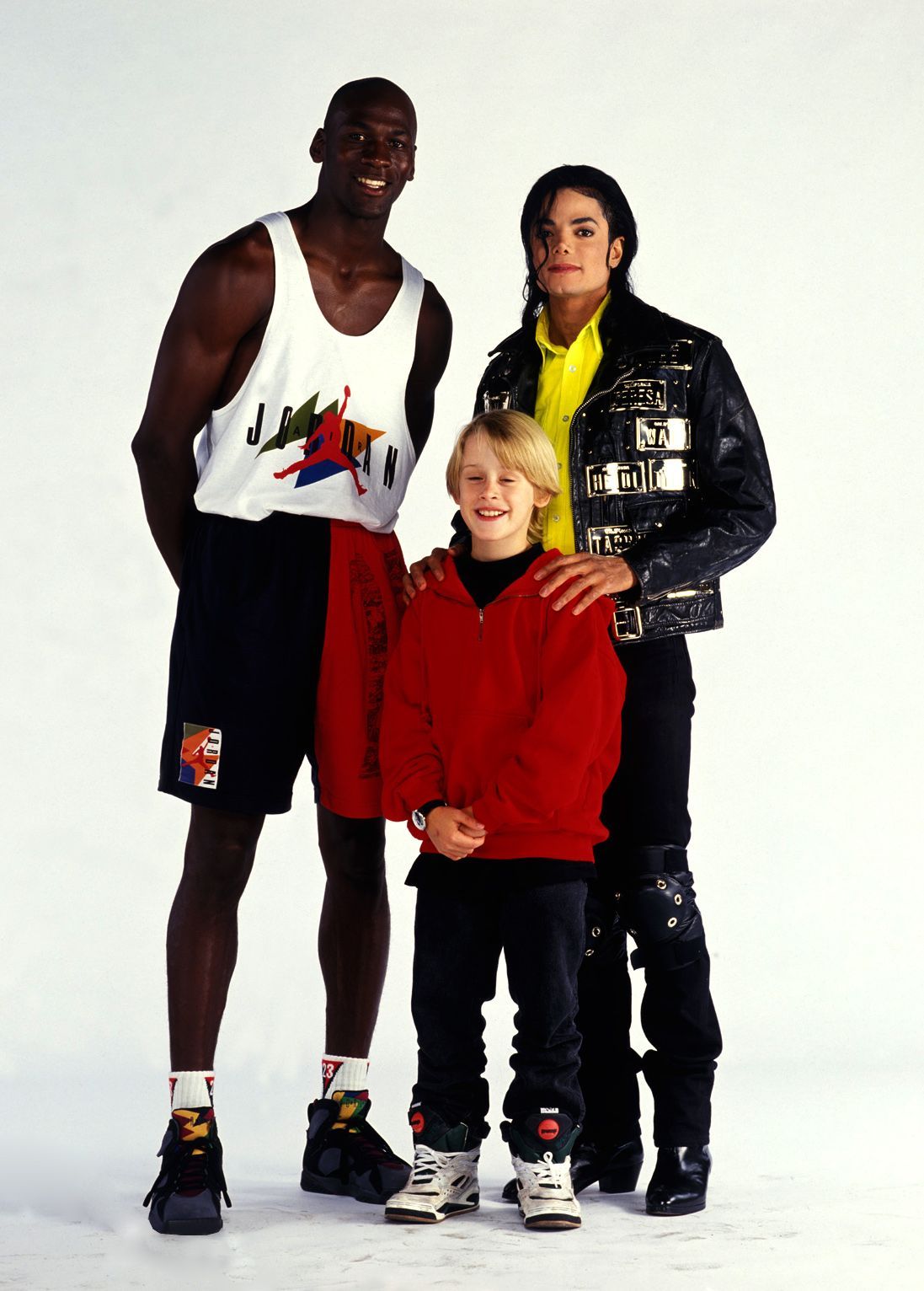

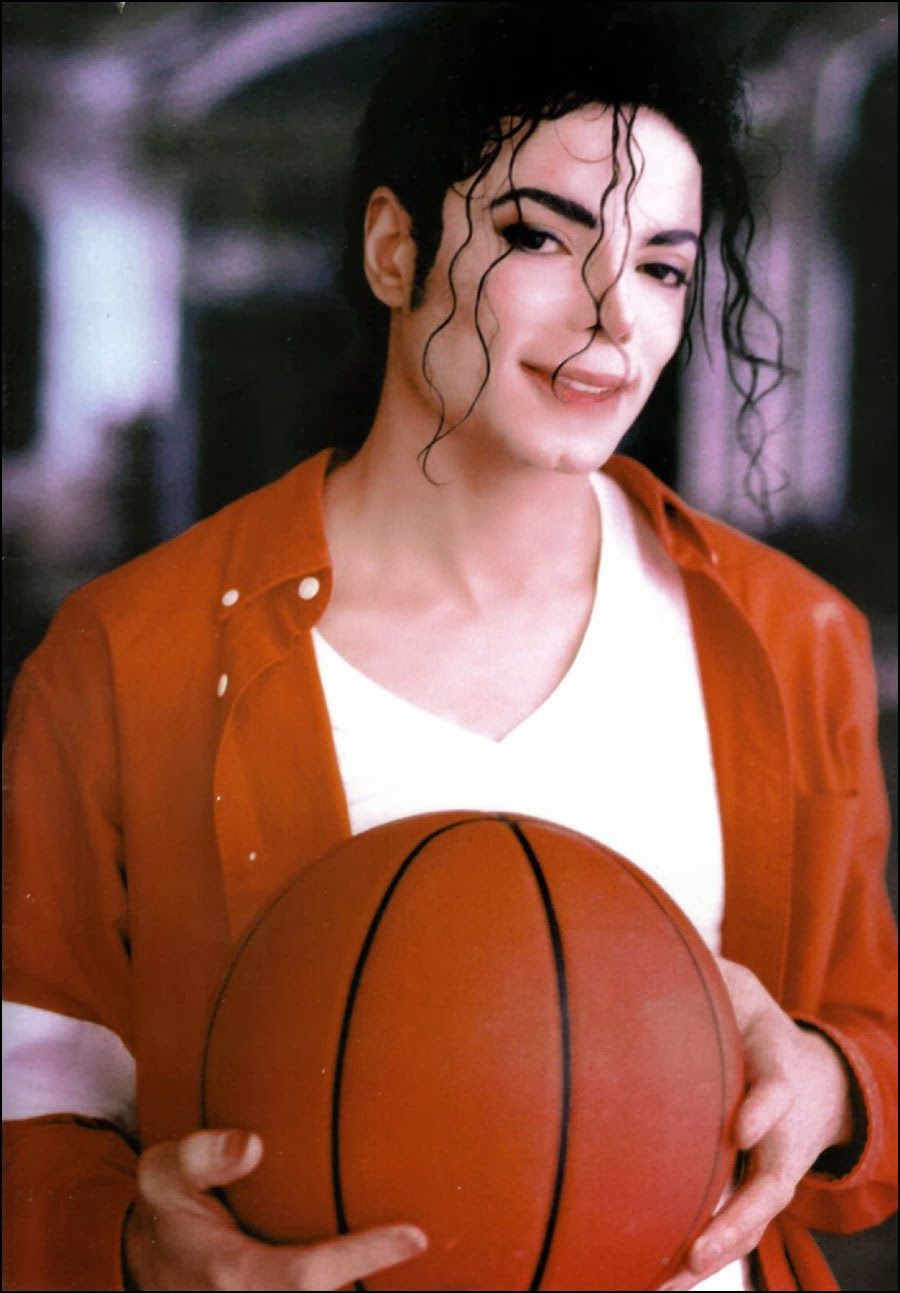

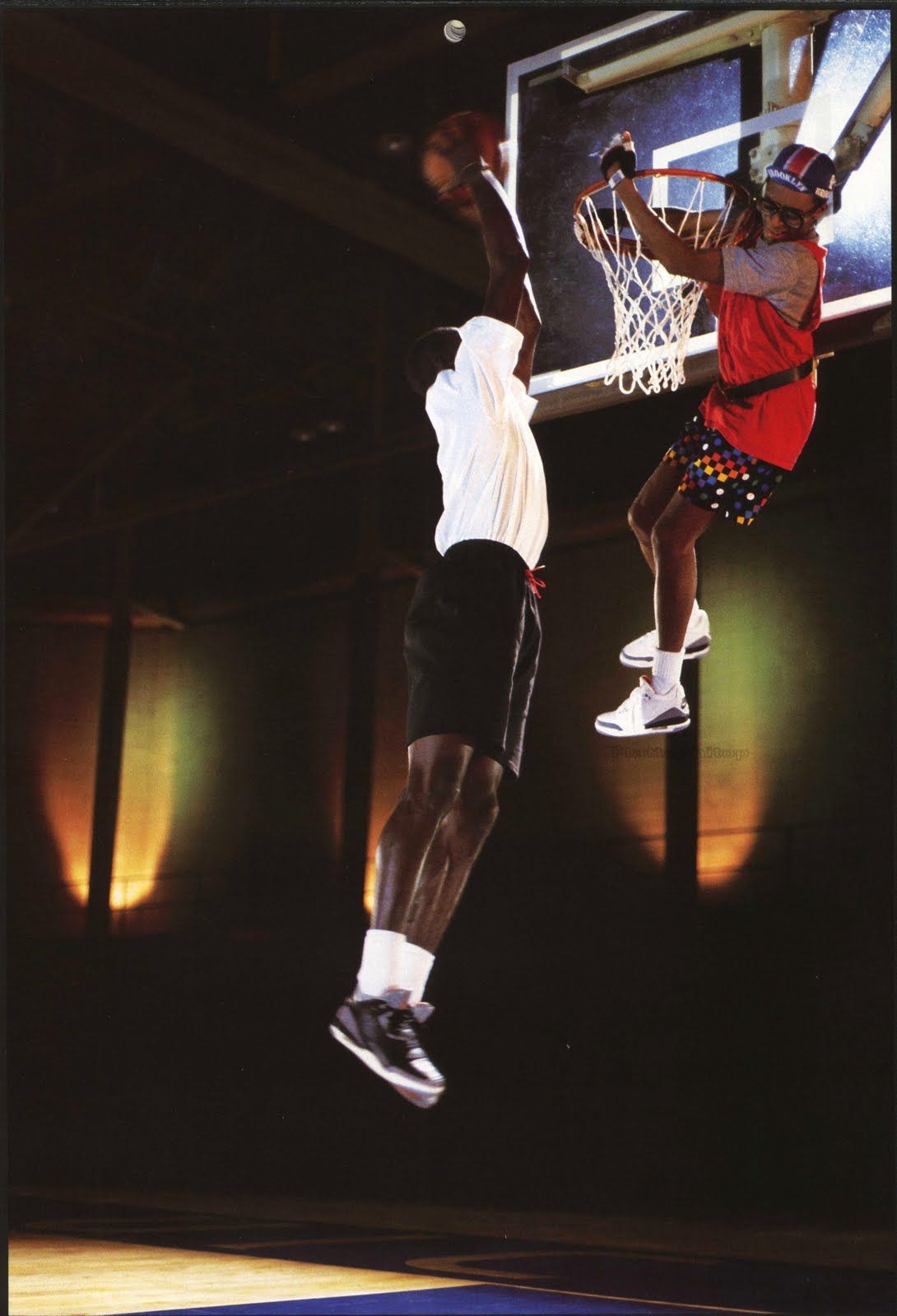

The two also found themselves together, in Jam's music video: the two biggest stars of American entertainment - and therefore world entertainement - in front of each other in a video all in all banal, but iconic in its meaning, which showed the world how black excellence had become American excellence.

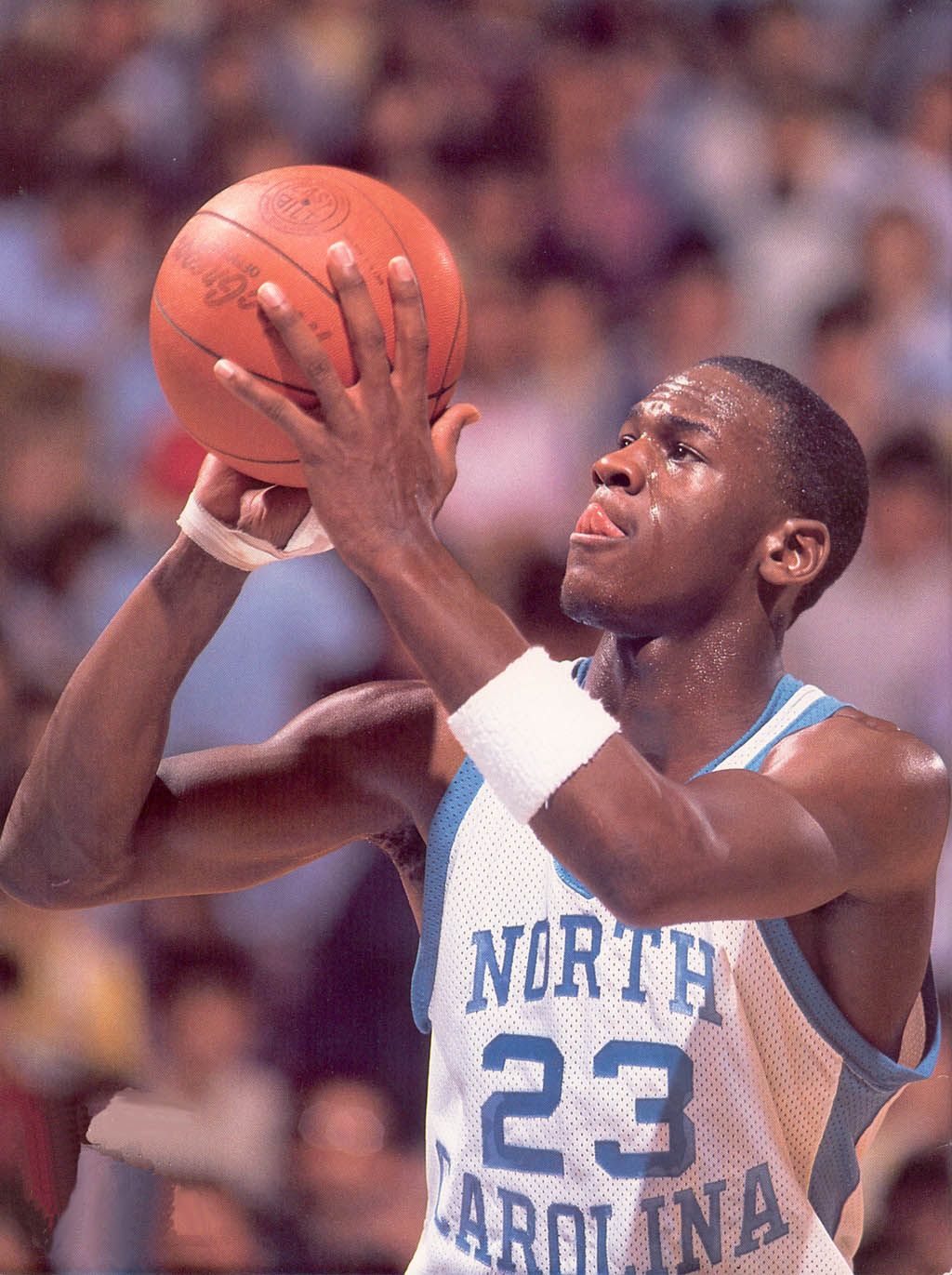

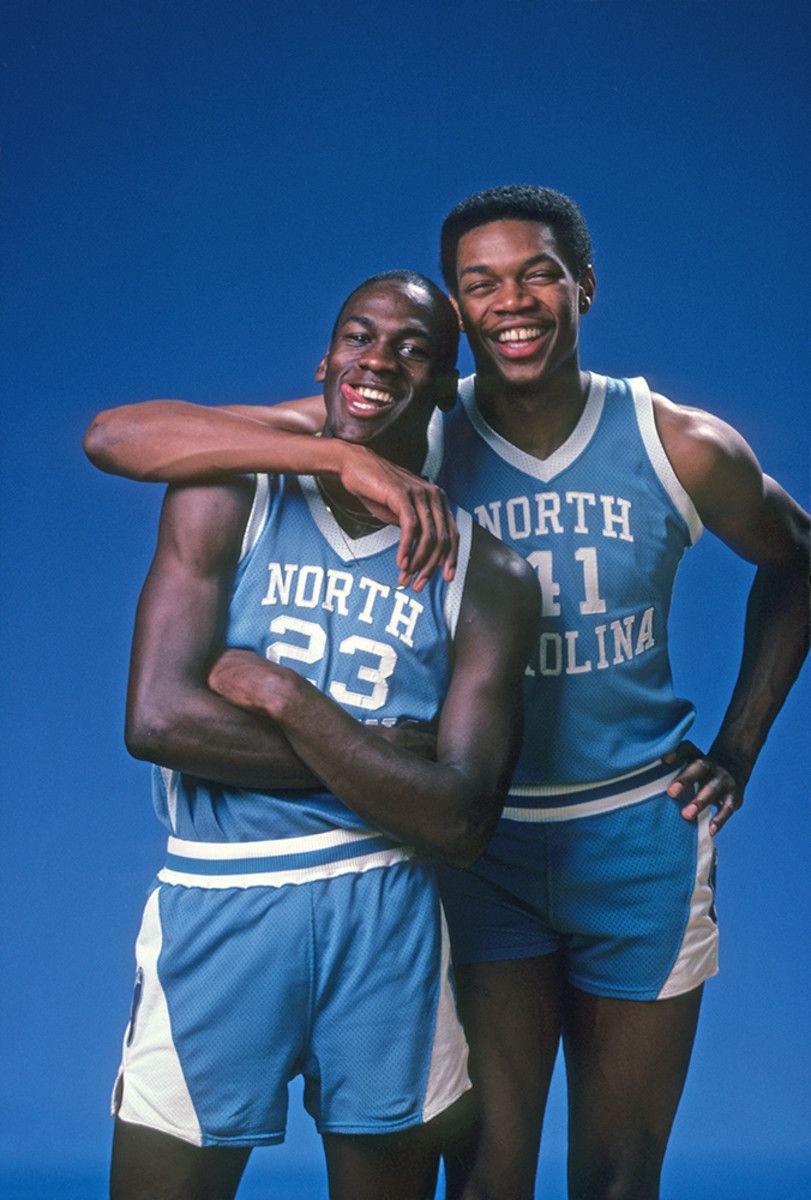

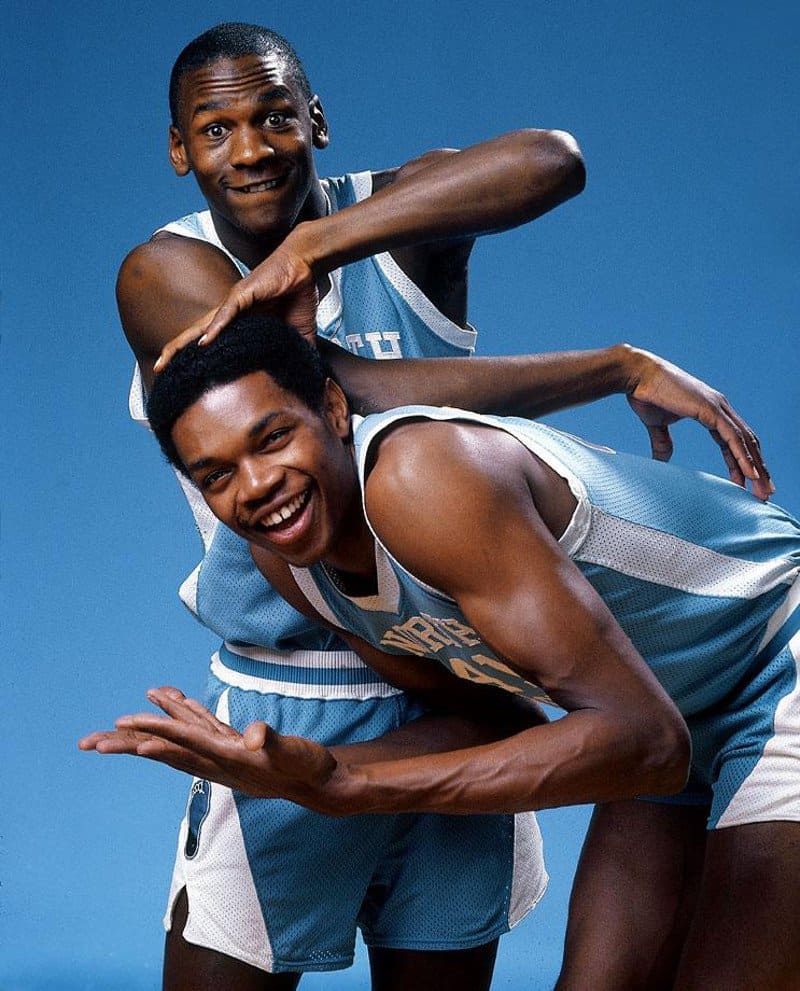

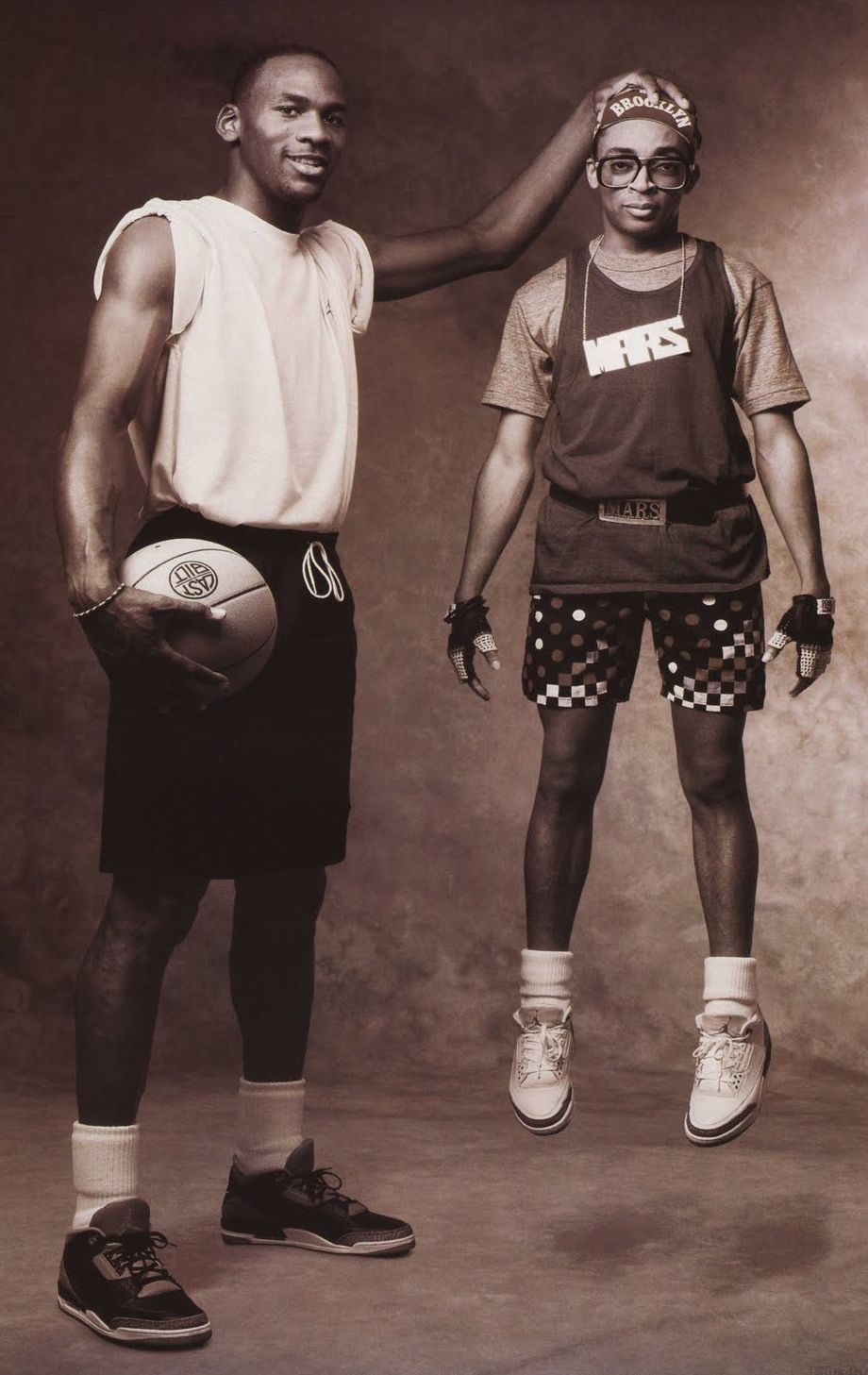

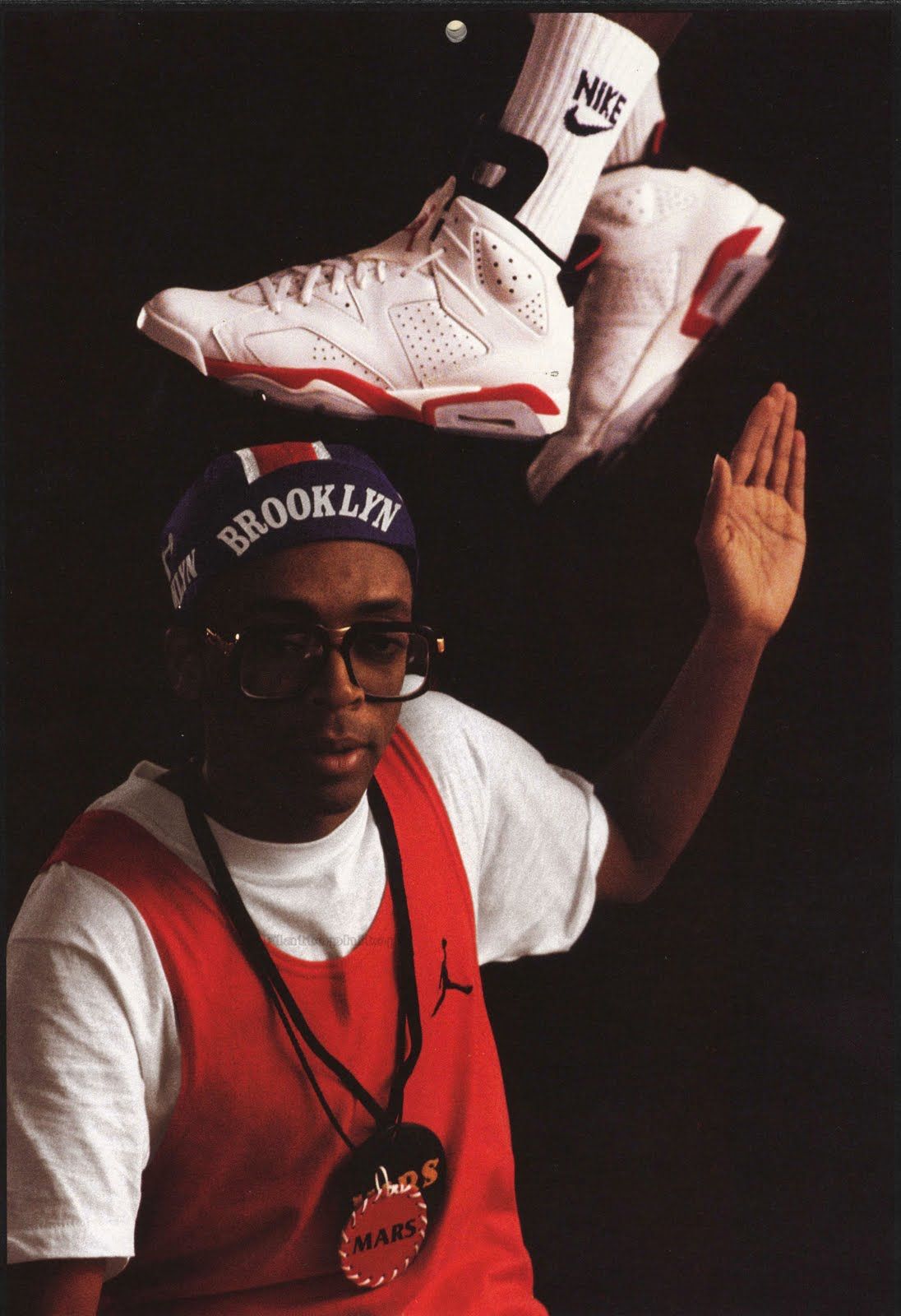

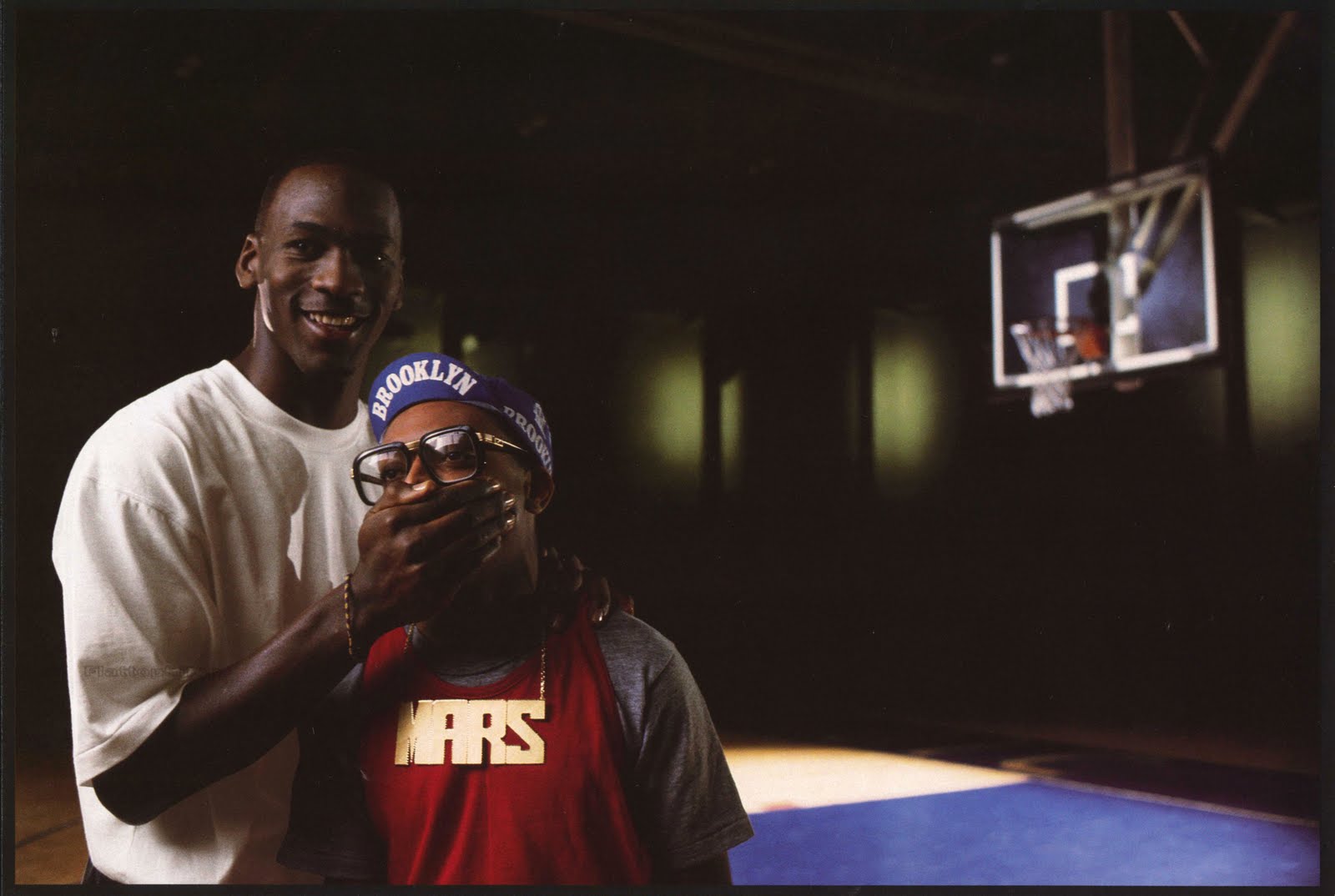

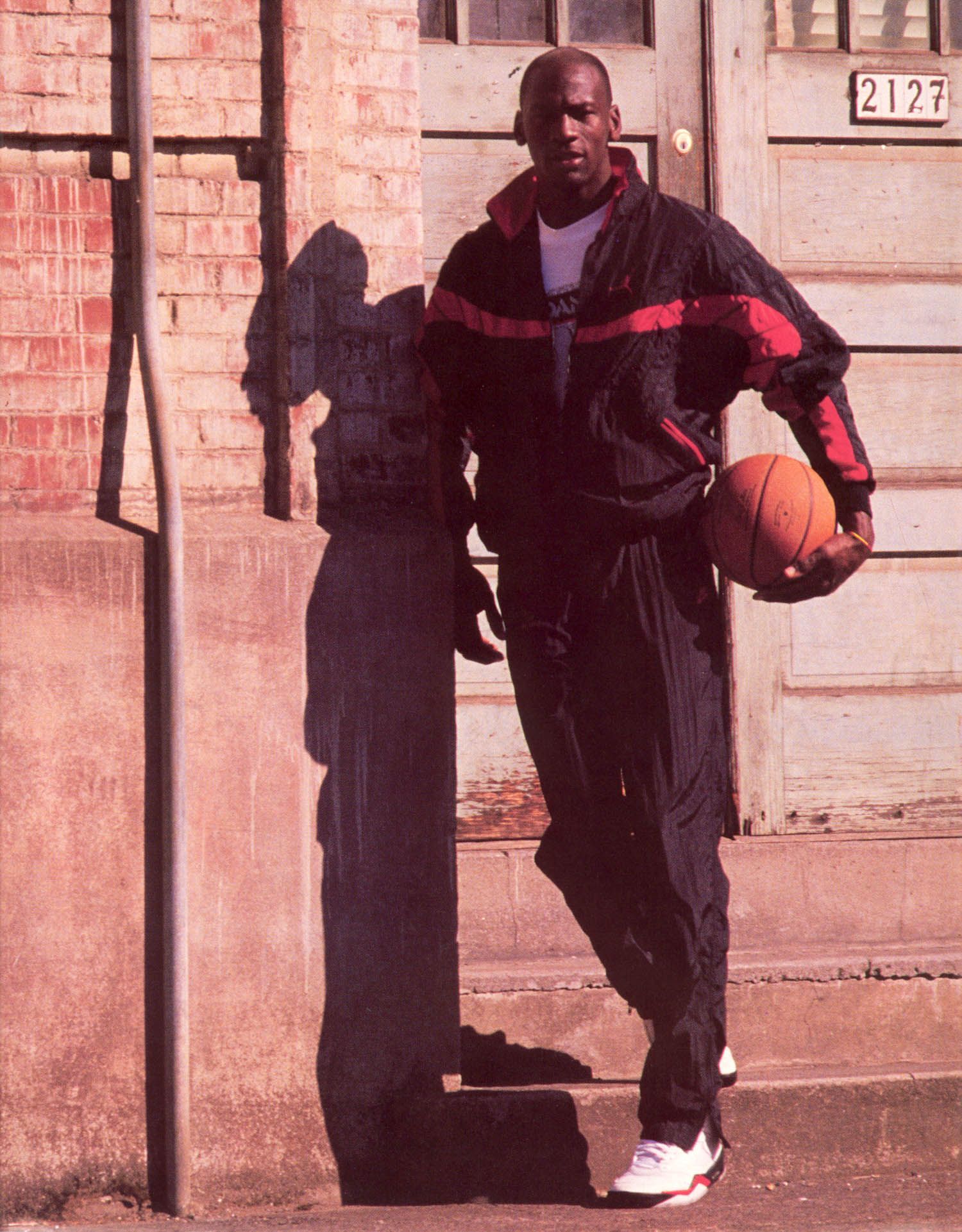

At that moment Jordan and Jackson were completely free to be who they wanted. If Michael Jackson had entered the music industry when he was ready for his commercial explosion, the same thing is true when you think of Michael Jordan and the NBA. MTV and the NBA were expecting nothing but two stars of that rank to make the 80s and 90s the best in recent entertainment history. Billie Jean was the first video of an African-American artist ever broadcast on MTV, in which Jackson's figure entered and consolidated into the homes of Americans as a generational idol. In his book, The Crossover: A Brief History of Basketball and Race, from James Naismith to LeBron James, Doug Merlino describes how Nike and Jordan's team, led by his agent David Falk, tried to catalyze Jordan's outburst by referring him to the kind of black-entertainment that was comfortable for the white middle class, an entertainment represented by non-breaking figures, like Bill Cosby or Oprah Winfrey: "The resulting commercial was Spike Lee playing Mars Blackmon - a character he had previously played in his 1986 film "The Darling" - a Jordan maniac who turns around the star and yells "It's gotta be the shoes"!

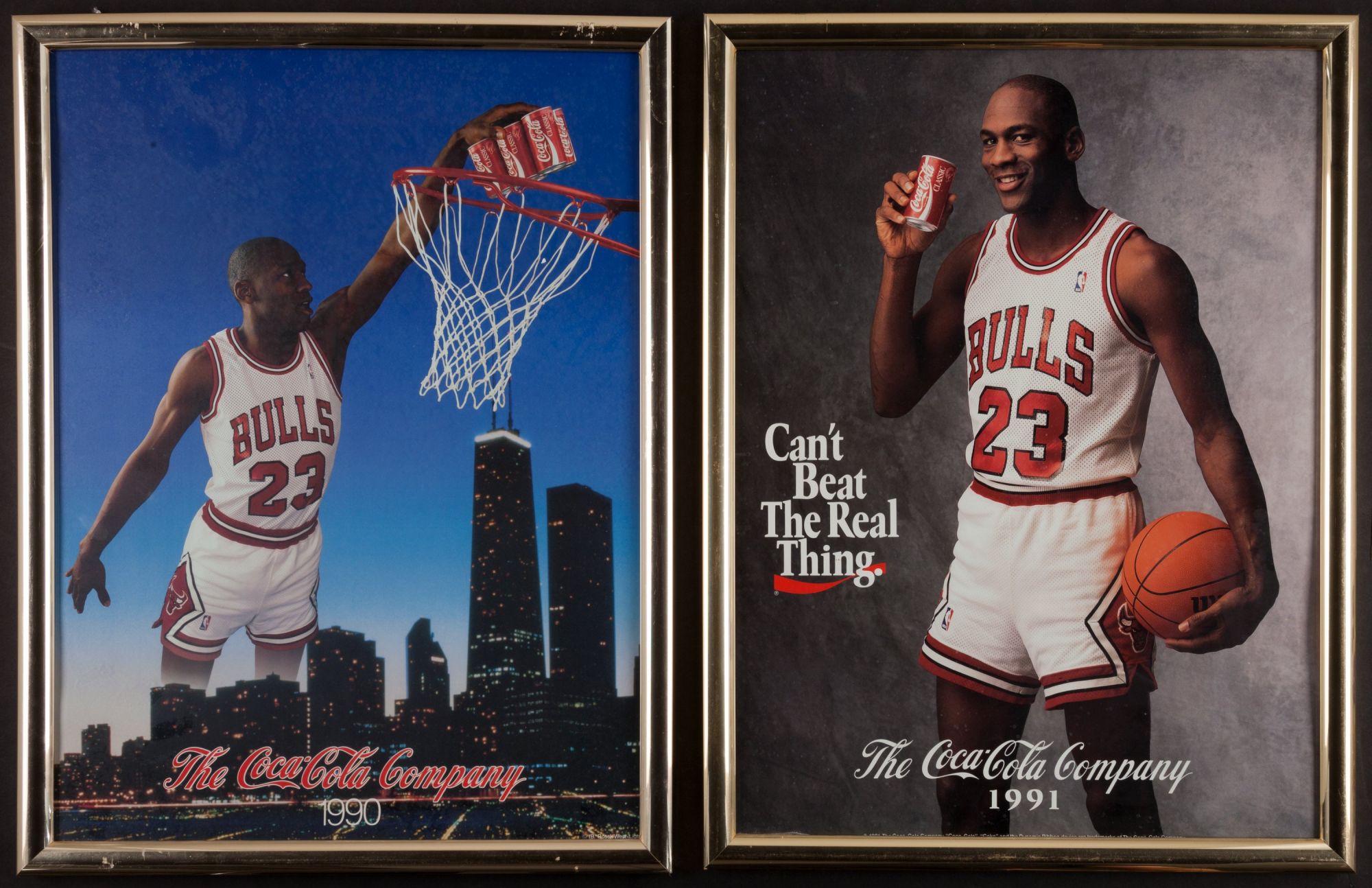

A real personification of Michael Jordan is put in place, which from that moment on becomes the face of the major companies in the country, from Coca-Cola to McDonald's, through Chevrolet and Wheaties, to the epic of Space Jam, arrive, of course, to Gatorade. The commercial of Gatorade was the one that threw Jordan's figure into the stratosphere. "I wanna be like Mike" became the mantra repeated to an entire generation of young Americans. He was taking an African-American and making him the aspirational model of an entire generation of white American kids: only 10 years earlier such a thing would have been unthinkable for American industry.

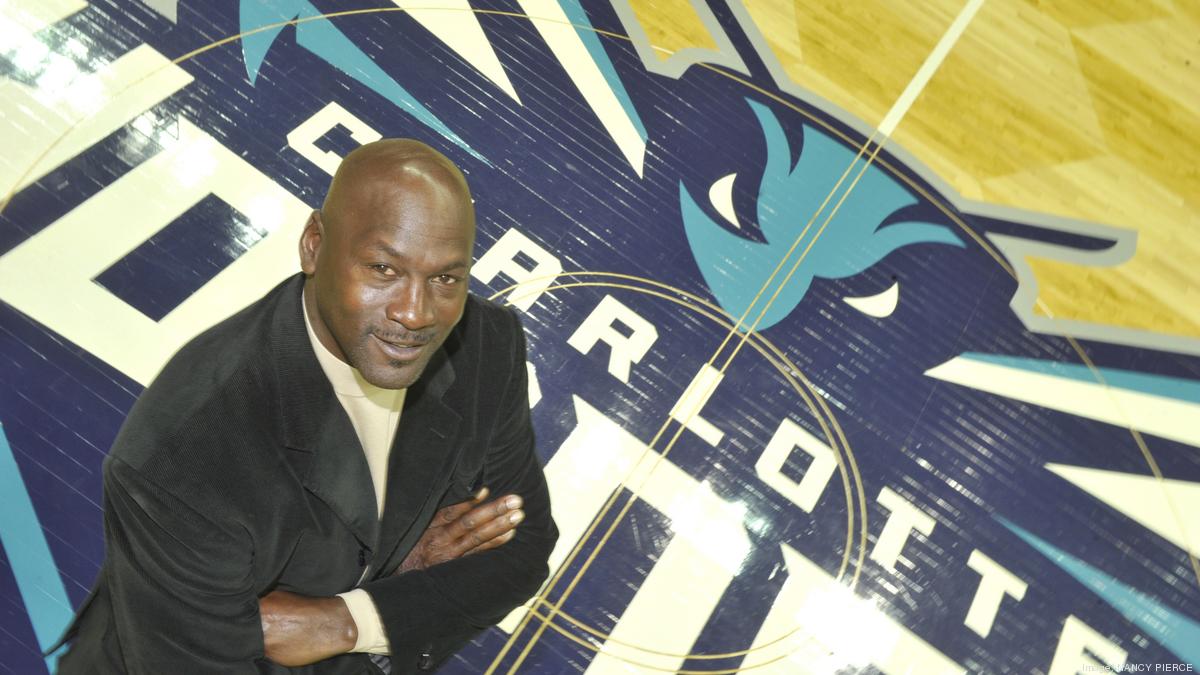

In 2014, Donald Sterling, the wealthy owner of the Los Angeles Clippers, was intercepted while telling his girlfriend not to "bring blacks to his team's games." At the time, Sterling was the longest-serving owner of an NBA franchise - along with Jerry Bass of the Lakers - but the backlash against him was not long in coming, until Sterling was banned for life by the NBA, and forced to sell the team. The first to speak was Magic Johnson, immediately supported by Michael Jordan: "There is no room in the NBA - or anywhere else - for the kind of racism and hatred expressed by Mr. Sterling...". At the time, Michael Jordan was the owner of the Charlotte Bobcats, who are now called the Charlotte Hornets, and was the sole owner of a non-white NBA franchise along with the Sacramento Kings' Vivek Ranadive. Jordan had acquired the franchise in 2010 from Robert Johnson, who in turn was the first African-American owner of an NBA franchise. Since then, the Hornets have been one of the NBA franchises with the highest percentage of African-American executives.

"Michael Jordan's importance as a player is counterbalanced by his being a unique owner. It's pivotal for young minorities to see that there are other options besides becoming a professional player, and that there are so many opportunities to work in the world of sport as presidents, general managers, COO and yes, even as an owner. In the age of the Donald Sterling nightmare, the NBA and our society need Michael Jordan now more than ever and they need people of color to become owners in the near future," Dr. Richard Lapchick, director of the Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sport, once said in an interview with ESPN.

Michael Jordan's role as a black entrepreneur has often been underestimated and overshadowed by his actual participation in social issues. Roland Lazenby once said: "I would say that MJ's story is a story of black power, not the black power of protest and politics, but the black power of the economy." In an environment - that of American professional sport - made up of a huge majority of white owners and black players, in which even Adam Silver (the NBA commissioner) has proposed abolishing the term "owner" because of a slave heritage, Jordan's figure takes on an all too often underestimated weight.

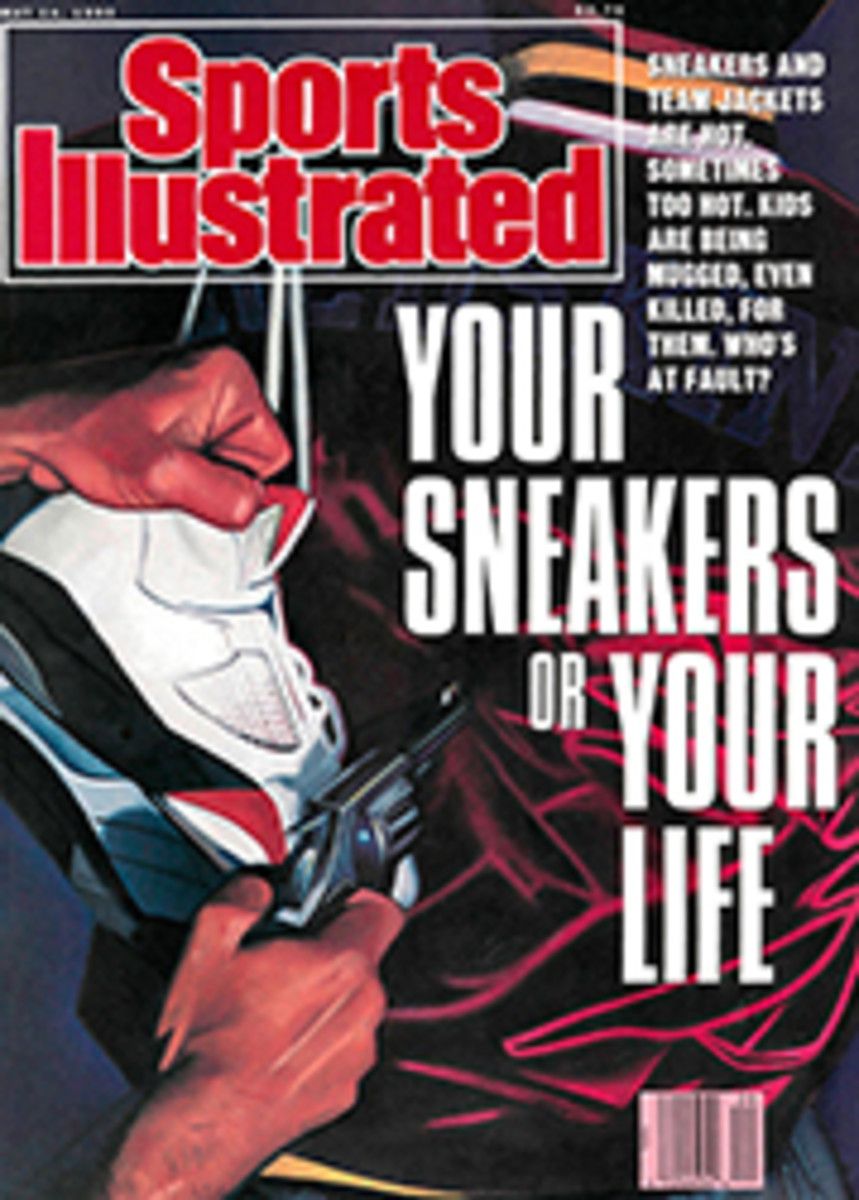

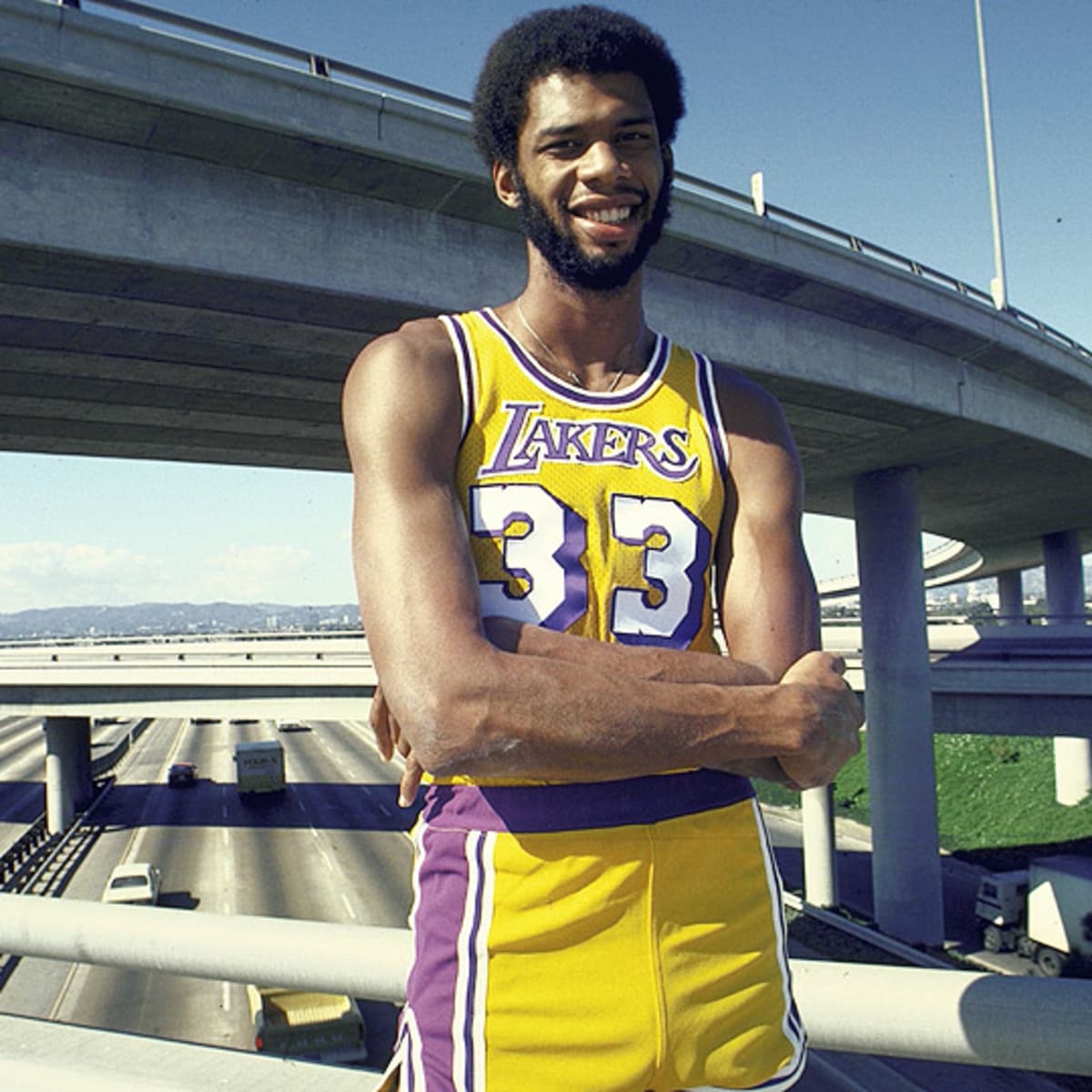

Jordan, who finds himself a franchise owner and in a prominent position within the brand that bears his name, is a very different person from the player Jordan. No other company within the Nike group has had as many high-level African-American executives as Jordan brand, "Michael's willingness to hire, support, and promote minority leaders through his businesses has been remarkable," Larry Miller, president of Jordan Brand, once said. It is difficult to judge the words of Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, a true legend in the civil rights struggle, who, speaking of Jordan, said how he preferred "commerce over conscience". If it is true - as it is true - that the agreement with Nike has earned Jordan over a billion since 1984, and that more than once Michael Jordan has been accused of having "starved the block", with the various acts of violence and death associated with Air Jordan, on the other it is necessary to contextualize the years when Michael Jordan became "His Airness".

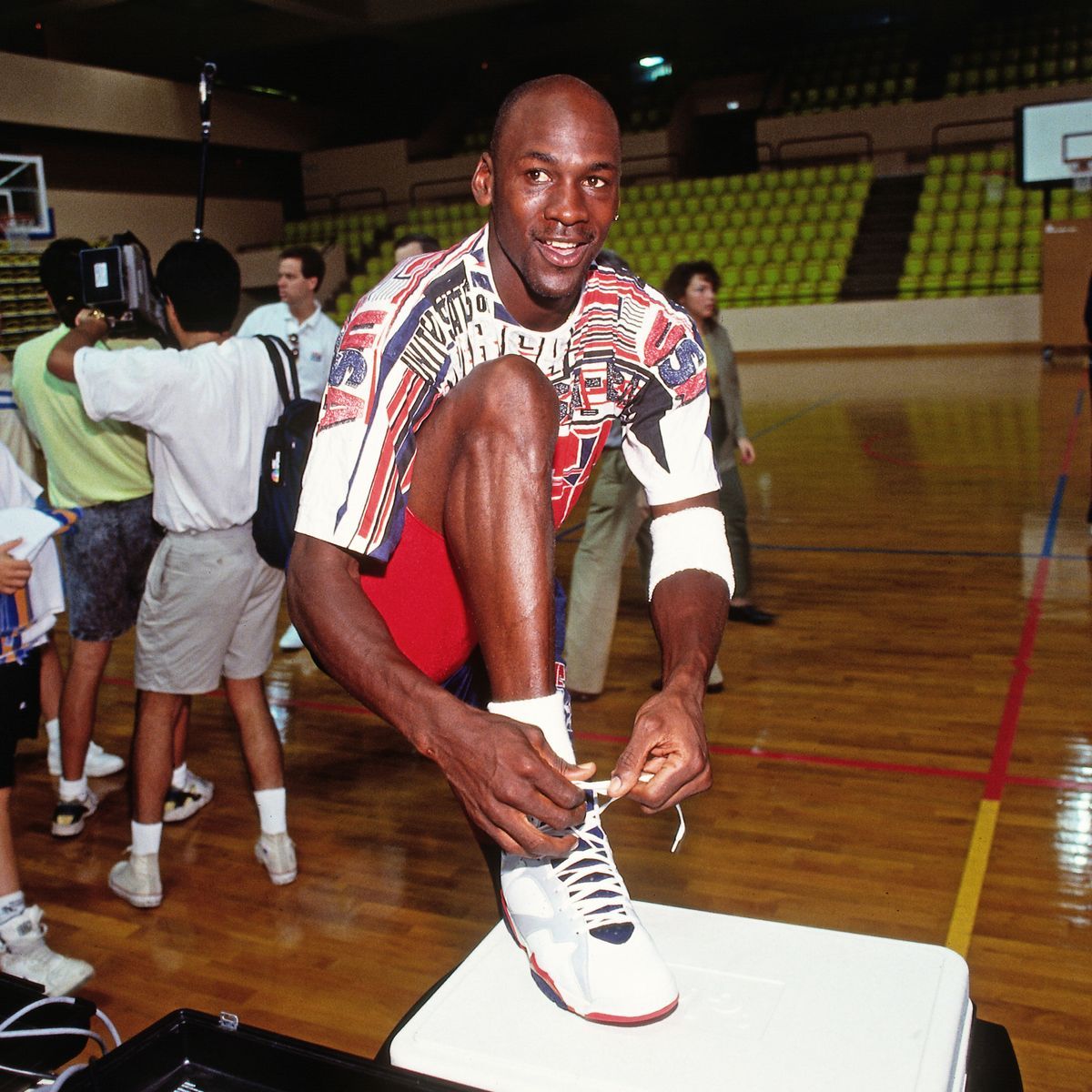

It wasn't the 60s and 70s of the Green Book, nor the '10s of Black Lives Matter, it was the 90s, and Michael Jackson was the cultural and, if not, U.S. politician who exported their idea of entertainment. As Adam Silver recalled in The Last Dance about the Dream Team: "Barcelona '92 was perhaps the first real pop culture moment in the history of sport, we were, in fact, exporting Americana."

In his essay, Coates write: « I wonder what he might be, if he could find himself back into connection, back to that place where he sought not a disconnected freedom of “I,” but a black freedom that called him back—back to the bone and drum, back to Chicago, back to Home». When Coates talks about "the disconnected freedom of "I," he implicitly refers to what is called the "Generation Me" - that of the American baby boomers described in Tom Wolfe's essay The Decade of the Self - to which Michael Jordan is a full member. In Young, Black, Rich, and Famous: The Rise of the NBA, The Hip Hop Invasion, and the Transformation of American Culture, Todd Boyd describes Jordan as "the godfather of selfish behaviour", an attitude that also comes out of Sam Smith's controversial book Jordan Rule. One of the characteristics of Generation Me is the contrast to Generation We, that of the civil rights struggles of the 1960s, Kareem Abdul Jabbar and the Black Panthers, protagonists of a chronologically close era but light years away from the pop globalization of the 90s. The years when African Americans began to become global stars.

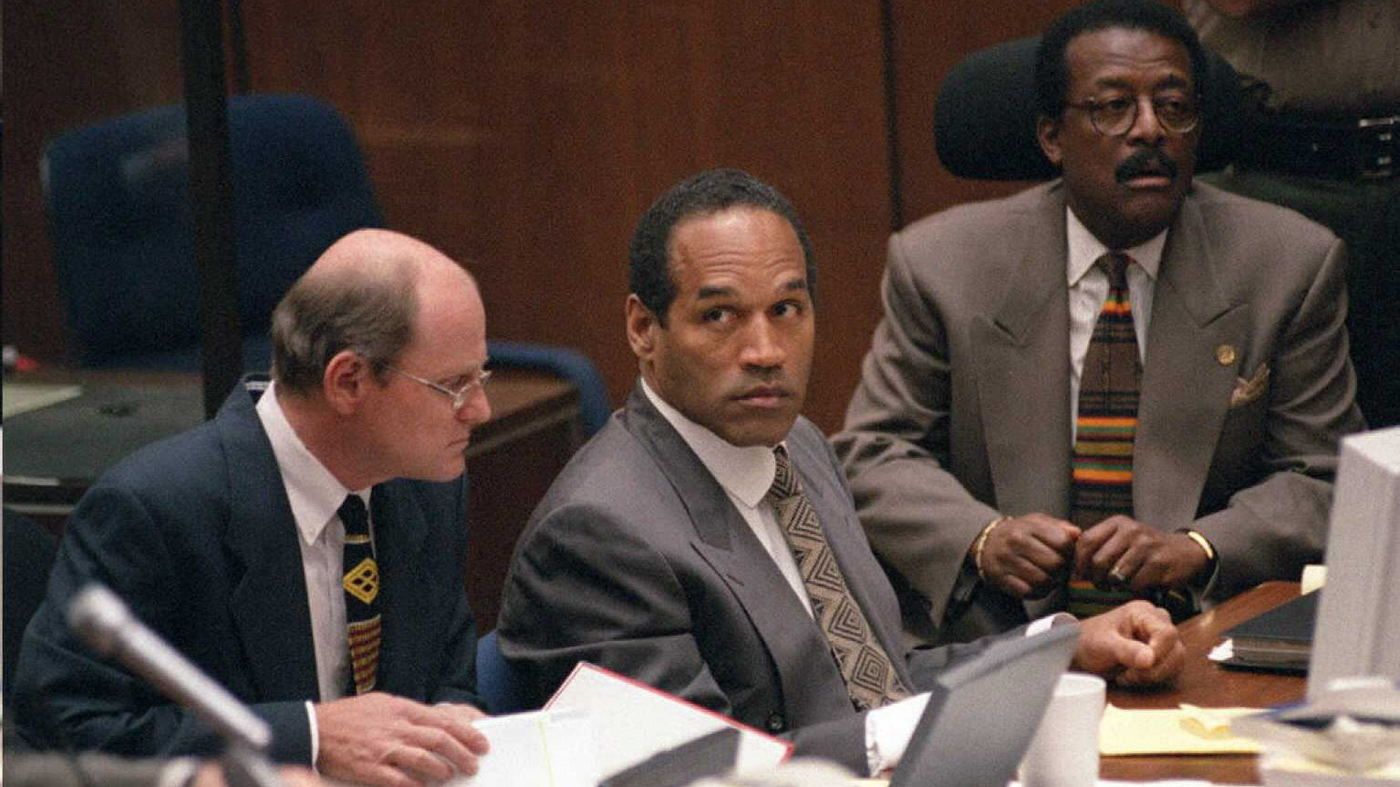

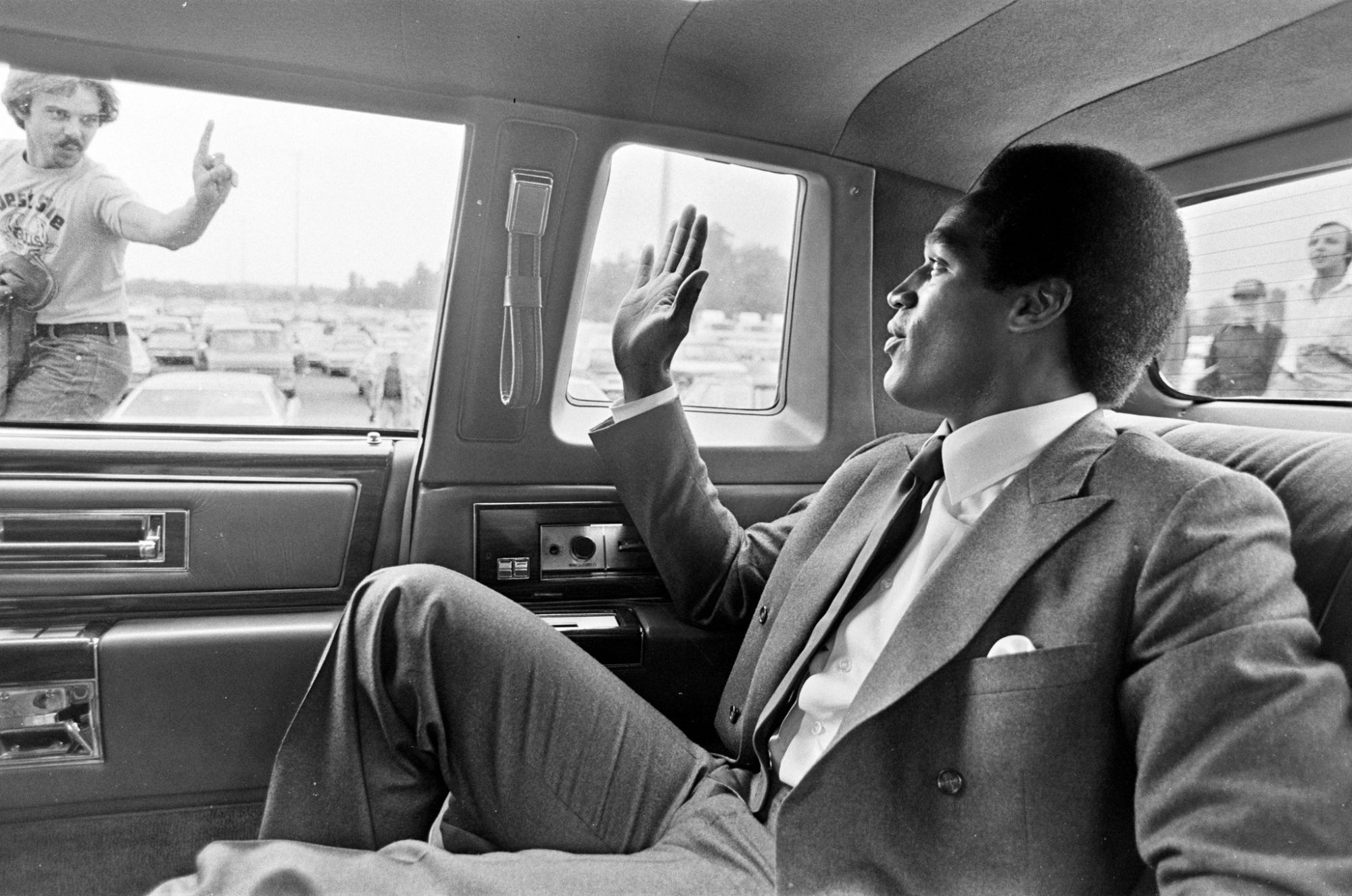

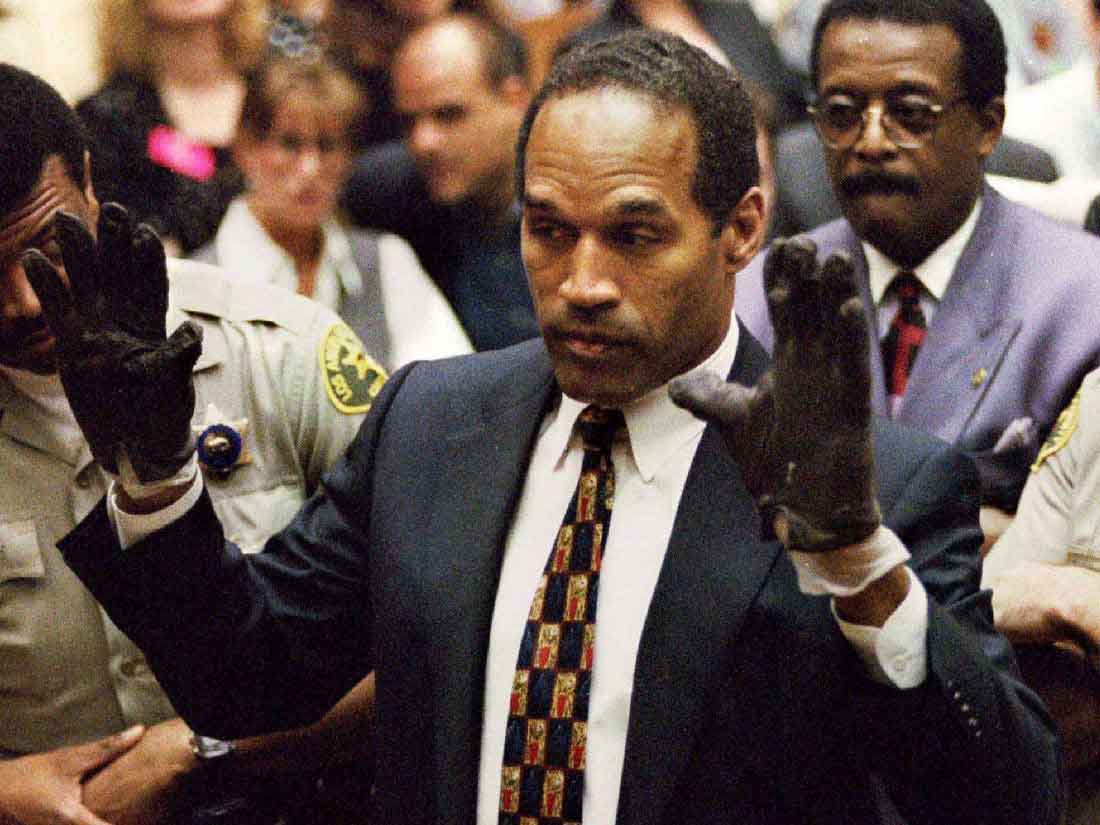

On June 13, 1994, Nicole Brown and Ronald Lyle Goldman were found dead at Brown's Los Angeles mansion. Brown was the ex-wife of one of the most famous players in the recent history of American football, who later became a real protagonist of the country's popular culture: O.J. Simpson. O.J. was charged with the murder, resulting in the most mediatically covered trial in the country's history - resulting in a thousand films and documentaries and in the famous scenes of the glove and the expression "I'm not black, I'm O.J.", then also mentioned by Jay-Z in The Story of O.J. Simpson probably never uttered that phrase accurately, just as the famous "Republicans Buy Sneakers, too" attributed to Jordan was extrapolated from the speech. In fact, however, the two expressions have entered American pop culture as explicit explanations of the complicated relationship with the race of two figures three the most important of the US sports scene. "The guy from Carolina is the new me. Take him," O.J. Simpson once allegedly told the executives of Spot-Bild, the sneaker brand he was a spokesman for and who came close to signing Jordan. If Spot-Bild does not resonate in the collective memory today it is because the brand of Hyde Athletic Industries has then evolved into Saucony, a brand perceived mainly as "white", as Kenya Barris also recalls in an episode of "#blackAF".

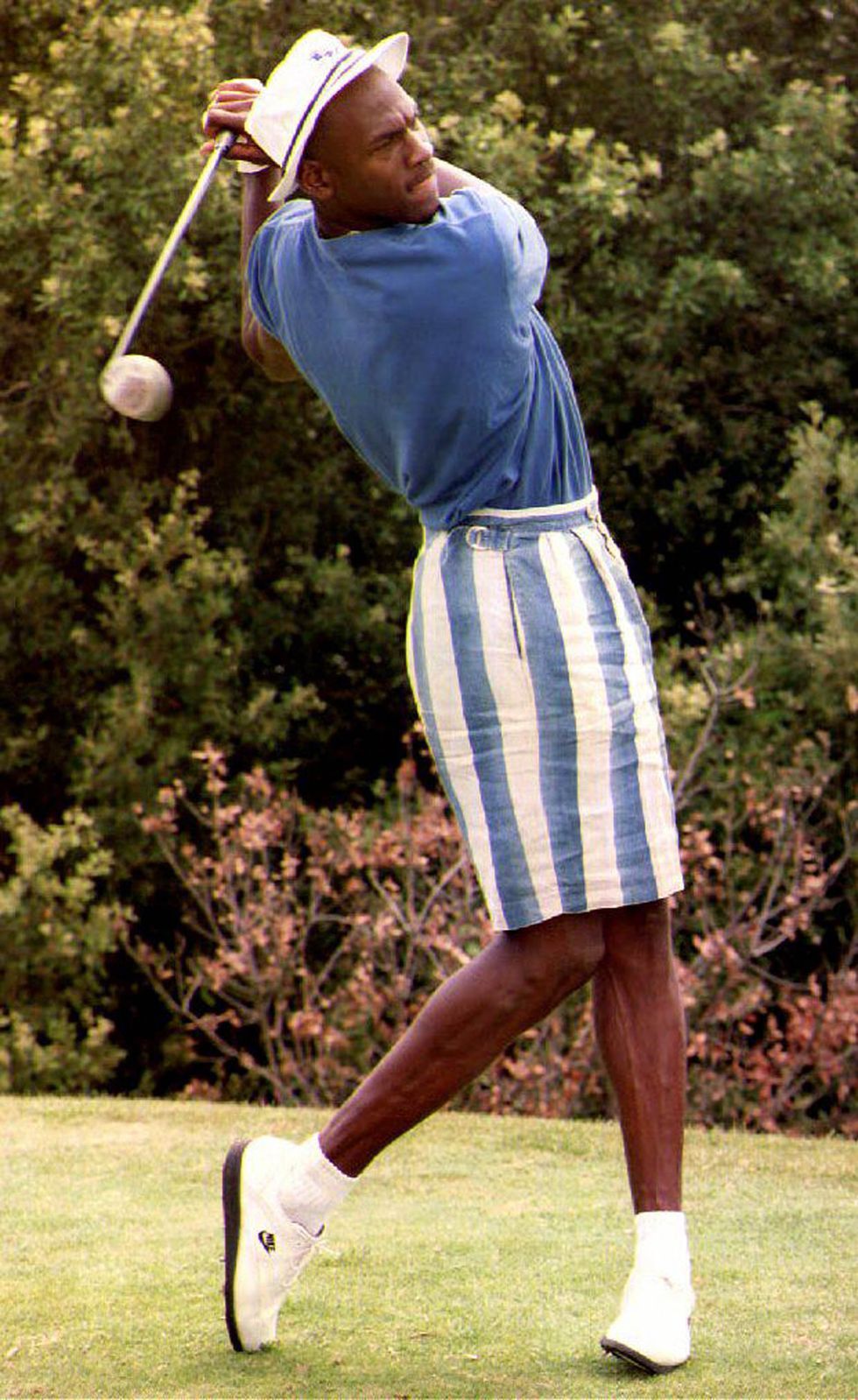

Pulitzer Prize winner Wesley Morris, in a commentary piece on The Last Dance, wrote how Jordan "made "cause-free" celebrity - and black "cause-free" celebrity - possible, indeed preferable than having to account for all things." Jordan was for years the cultural outpost of a type of sports and lifestyle that rejected the political and social commitment to the consecration of pop culture. Jordan, however, has done all this from his position of privilege in a society, the American one, which has never really come to terms with the institutional racism it is imbued with, and that the backlash of the election of Donald Trump, the Colin Kaepernick affair, has only exacerbated. Michael Jordan was the kind of celebrity who could skip the NBA champions' annual visit to the White House to play golf with a man then arrested for money laundering. And to do so without that decision ever being understood in any way as a policy. And if today, in the media age of Lebron James, his propaganda commitment to the civil rights of African Americans, that kind of figure seems almost unrealistic is because we have always shaped our expectations of the communicative power of athletes, and black athletes in particular, on what Jordan himself had been able to do. And that is to change the world, just not in the way that everyone asked him.