Who are the rural influencers? In China some farmers have become millionaires seeing their products directly on TikTok

The incredible and in some ways inexplicable success of the videos renamed "Indians who build swimming pools", (but also houses, villas, and even dog kennels), appreciated and re-shared both on YouTube and on TikTok, had to make us understand the potential of videos that are anything but extraordinary, frames of daily, normal, ordinary works. If in the videos of the pools the viewer - especially those with an obsessive compulsive disorder - remains enchanted by the precision, order and skill of the workers, a much more bucolic, naturalistic but no less commercial content, is enjoying great success in China, in a perfect synthesis between entertainment and business, in a new way of understanding teleshopping that Giorgio Mastrota will not be able to help but import also in Italy (or at least we hope).

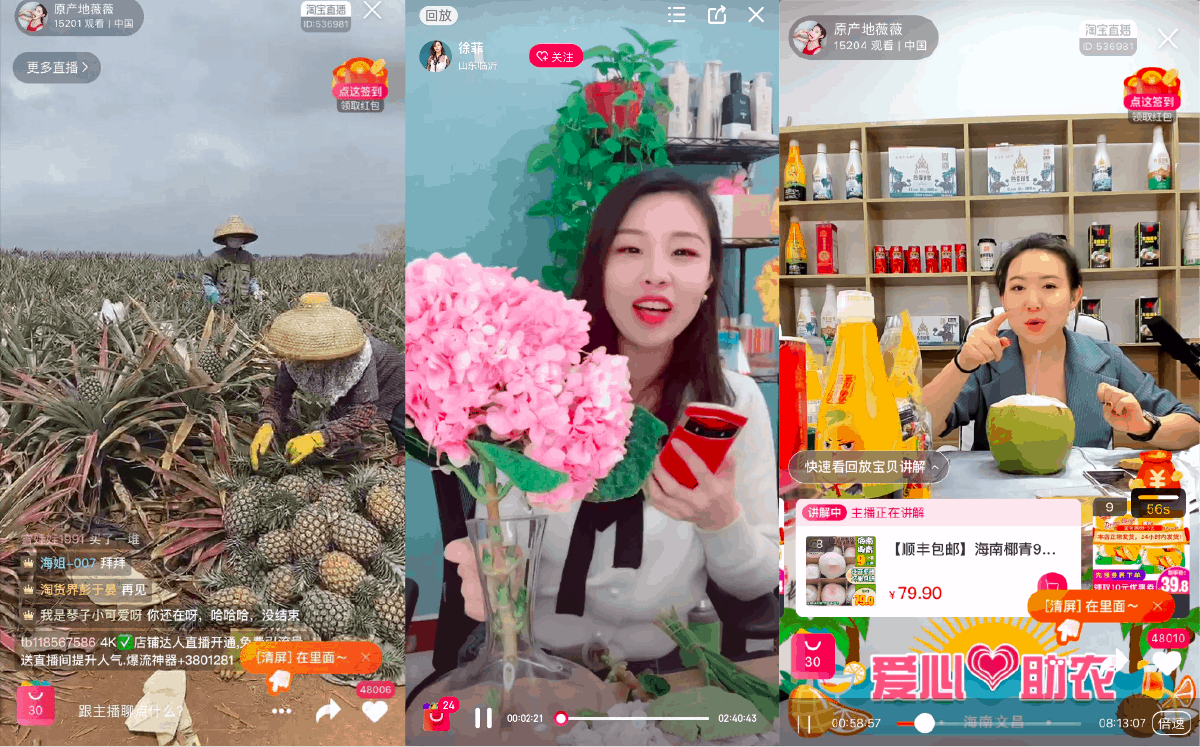

On several Chinese social media, such as Douyin, the Chinese version of TikTok, also owned by ByteDance, videos of farmers, farmers and growers who have reinvented themselves as influencers, or rather, out-of-the-box sellers, are multiplying, transforming their daily work - collecting and then selling fruit and vegetables - into a show, a simple idea, to sell a lot. This is the case of Jin Guowei, a farmer from Yunnan province, better known as Brother Pomegranate: 7.3 million followers and 300 million yuan ($46 million dollars) of sales in 2020 alone. The time when he managed to sell pomegranates worth 6 million dollars in just twenty minutes remains legendary. Another farmer, Guo Chengcheng, can count 2.5 million followers on Douyin, who can directly buy what she promotes in her live shows, through a special link. In a sort of live teleshopping from the countryside, what the farmers show is immediately purchasable, not unlike a see now buy now fashion show. Chengcheng, for example, manages to accept up to 50 thousand orders per livestream, for a gain of about 9 million yuan per month, relying on the means and services of large e-commerce to deliver the purchased goods.

Both Guowei and Chengcheng are part of a larger movement, those so-called rural influencers who after years spent in the cities have decided to return to the countryside, a decision linked both to the pandemic emergency and to the decisions of the Chinese regime. A combination of factors - the desire to leave big cities preferring a return to nature in small towns and communities, the desire to cook more and better during the lockdown - have meant that last year was a crucial moment for the growth and success of reinvented farmers/creators, thanks to which millions of Chinese citizens have the opportunity to buy fruits and vegetables in live streaming , directly from the peasants, as at the market under the house. The success of these rural influencers also owes much to the visual and aesthetic component of their contents, uncontaminated landscapes, silences unimaginable in the city, which exert an important charm on the inhabitants of large cities.

At the same time, the return to the countryside is linked to a precise plan of the Chinese government, which wants to return to the principle of san nong, a program that wants to give new impetus, also through state support, to agriculture, rural areas and farmers. In an updated version of this goal, the streaming e-commerce of farmers would be an innovative and effective way to revive the sector, also giving it a new image, fresher and more contemporary. At the intersection of these instances is Li Ziqi, the most famous video blogger in China with over 15 million subscribers to her YouTube channel (a platform that has been banned in China since 2008 but for which in this case an exception has been made), which with sophisticated and well-edited videos tells the life in the mountains of Sichuan, showing another face of the country and telling its core values: patience, traditions, family, relationship with nature. All issues that have led many to hypothesize that Li Ziqi was in some way a product of the Chinese government, which through his figure and his videos would be the spokesman for the government and its political program.

Beyond the interference of the government, this new form of creator economy represents a very interesting attempt to adapt professions and jobs of the past, but still indispensable, to the tools of the present, able to amplify their scope and importance. In the months of the pandemic there had been much discussion about the possibility of trying to import into Italy the format of live teleshopping on social media of garments and fashion accessories, a content that works a lot in China and to which we are not yet accustomed, and which in fact in Europe there haven't been noteworthy attempts. Changing product, communication and in general aesthetics, more real and less glossy, could be a good way to experiment with this format also for us, starting from the campaigns to get to Milan.