Why don't brands open more archive stores? To be successful selling secondhand, you have to abide by the rules of the audience

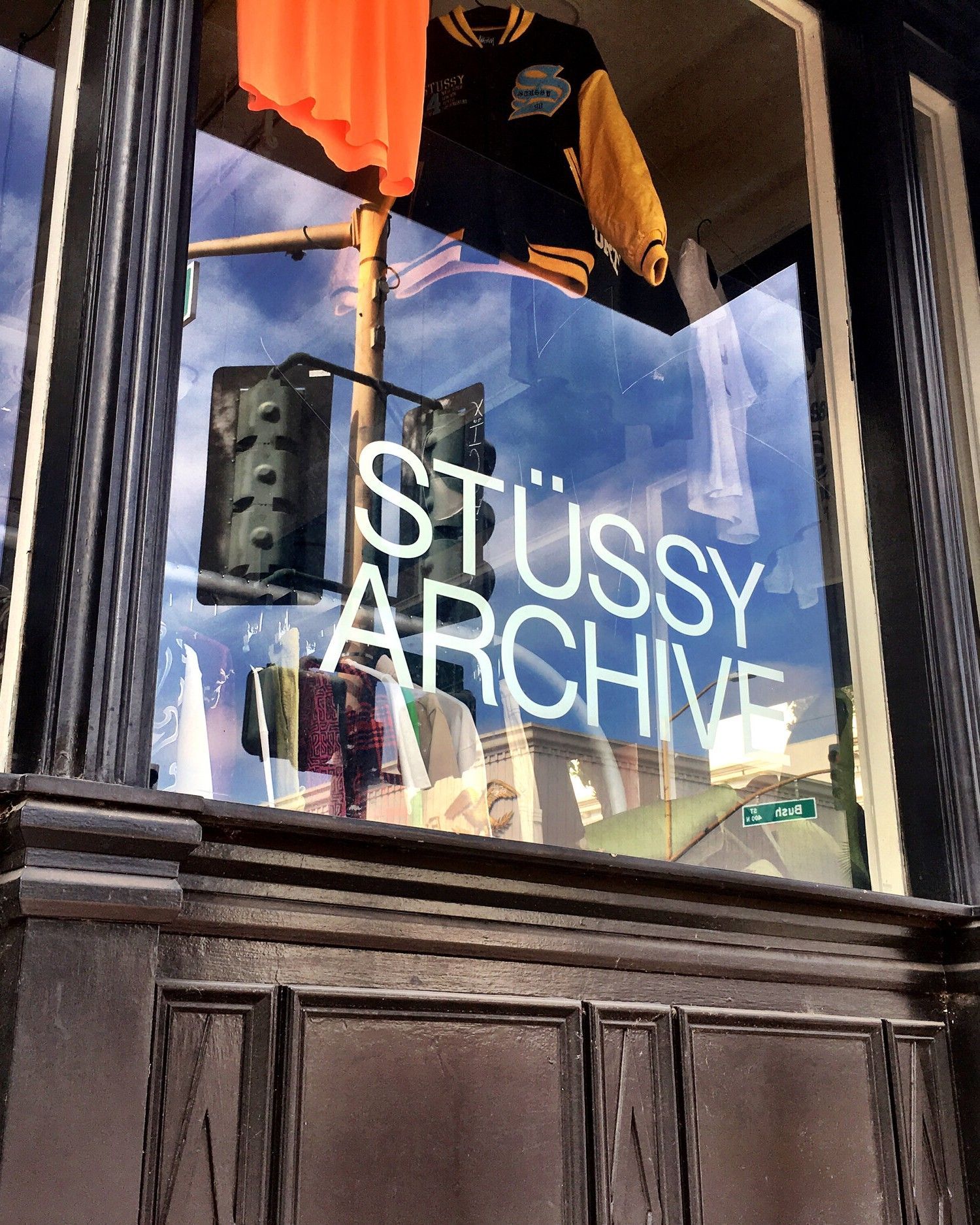

Today, in Brooklyn, on the street corner with Carroll Park, the new Stussy archive store will open. The store will remain open for the entire month of June, selling historical items of the brand, past collaborations, as well as artwork and furnishings, and it will be, in short and with all due respect, a sort of very rich clearance sale promising to find crazy deals, cult pieces, and even hidden gems in what we presume to be the brand's bottomless warehouses. The experiment is not new for Stussy: the first archive store was indeed opened in New York in the form of a pop-up for only three days in 2018, and the success was such that the brand opened a permanent one in California, in Santa Ana, just the following month. Stussy's decision to turn its archive (and we suppose, with a hint of cynicism, also its unsold stock) into a standalone retail experience, which perhaps also provides the thrill of the unknown to the customer who enters it as if it were a vintage store, is farsighted. Many brands and even several online multi-brand retailers have started to explore their possibilities with their own archive clothes - such initiatives, however, have had moderate success, mainly because when a brand sells its own garment, it does so at prices that are commonly not acceptable in the secondhand world. The truth is that we have reached a point in fashion where the secondhand clothing market is no longer just a simple Sunday hobby but a gigantic commercial galaxy that institutional fashion does not like at all.

Let’s list a few recent cases, without aiming for completeness: the most striking is certainly that of Rickie De Sole, daughter of the powerful Domenico De Sole, who leaves the position of vice fashion director at Nordstrom to join the board of Vestiaire Collective; this week, not only did an article by Grazia UK proudly headline How One Fashion Editor Bought A Designer Wardrobe On Vinted, Saving Thousands, but on Twitter, a user pointed out that a haute couture piece by Dior from a few years ago is for sale at a price higher than many cars; while the resell for Y2K pieces from Abercrombie & Fitch and Forever21, department store brands, has started to reach hundreds of euros in the United Kingdom.

Someone’s casually selling a Dior Haute Couture SS20 by Maria Grazia Chiuri dress and cape on Vestiaire Collective… i cannot lmao pic.twitter.com/3NuJDIh7HB

— Jude Macasinag (@judeisjude) May 21, 2024

A recent article by Vogue Business, referring to the case of a pair of Forever21 shorts resold for 200 euros on Depop, even talks about the phenomenon of flipping – the trick, very common among the “chronically on Vinted,” of buying a certain used item for a few euros and then reselling it for much higher amounts on platforms like Vinted, Vestiaire Collective, or Depop. In short, in 2024, buying secondhand is no longer a secondary option but the first choice. When, in a clear state of denial, high officials of the industry say that the economic problems of the entire industry do not derive from the now insane prices reached by the goods, preferring to justify the problems with macroeconomic reasons, they are voluntarily ignoring the fact that an entire generation of potential customers buys what they want on Vinted, Vestiaire Collective, and similar platforms, not to save the planet (even if ecology certainly feels better at the time of purchase) but because it simply costs less, there is no need to face the chronic size and product absences of luxury boutiques, and you do not feel embarrassed to look at the price tag under the gaze of a smiling salesperson who follows you like a police helicopter in GTA. Not only is it convenient and affordable, but spending time scrolling through these apps is something similar to gaming, almost like playing a slot machine.

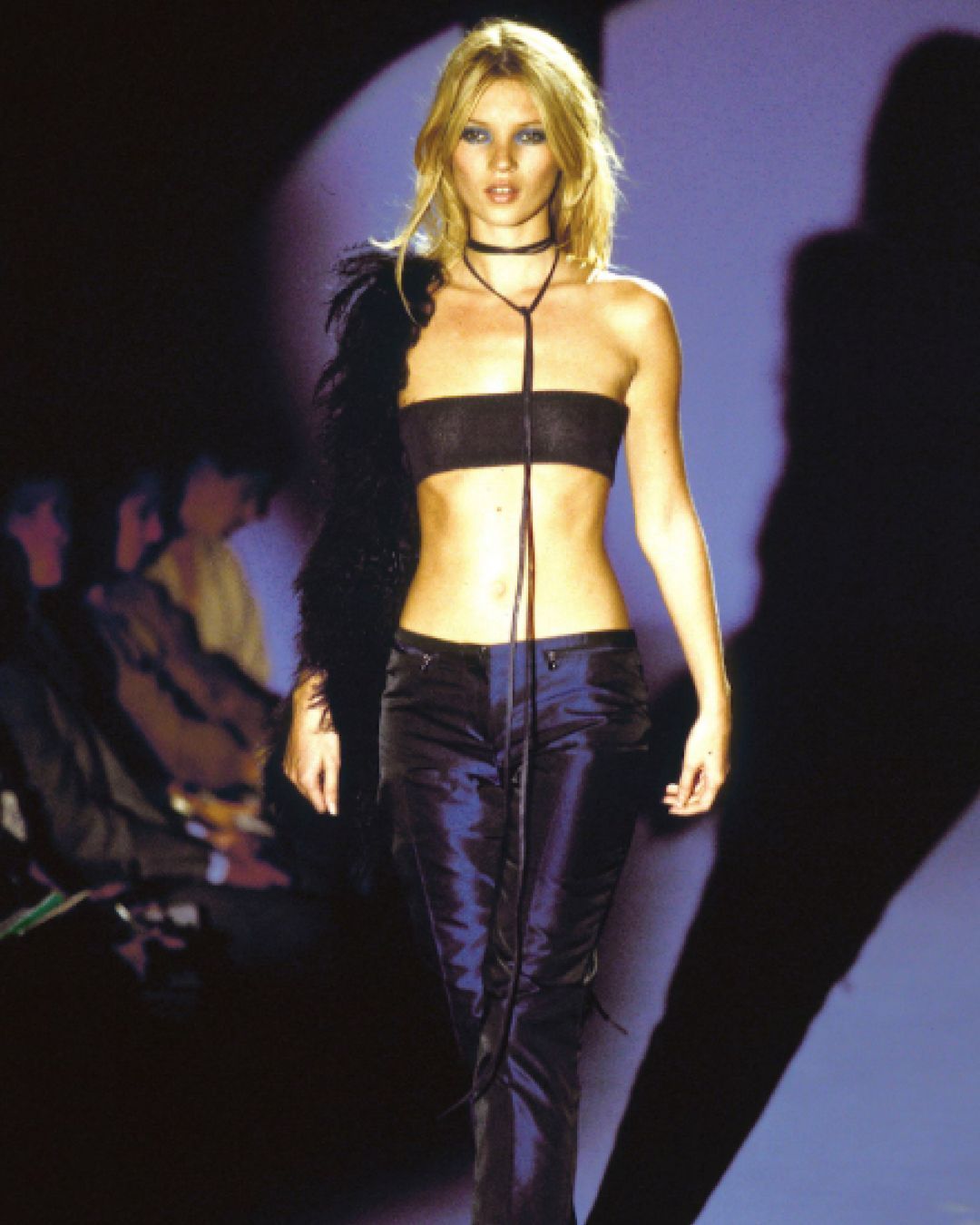

But let’s go back to Stussy and its archive for a moment. Over the years, Stussy has produced just about everything and is today considered the Chanel of streetwear, especially since its prices (although rising lately) are premium but still accessible to a very large part of the clientele. Stussy vintage is highly appreciated, moreover, especially if coming from the era when the brand still produced in the United States, and therefore, having such an archive available, why don’t other brands launch similar operations? The answer is simple: if you want to succeed in secondhand, you have to play by the audience’s rules. That is, low prices, flexibility, and little institutionalism: a bit like brands already do at their private sales. The secondhand market was born for the convenience of the end customer, and if several initiatives to sell "elevated" vintage by fashion brands have ended unsatisfactorily, it is precisely because they applied boutique or near-boutique prices. Surely, the introduction of secondhand has disrupted many of the plans and practices of luxury, exposing its way of operating as outdated, to which new generations do not really respond. Anyway, judging by what can be seen happening at all levels of society, by now, the future of fashion seems indeed to be secondhand, and jumping on the secondhand train, in a way that makes everyone happy, will become something essential for all brands - including luxury ones.