Balletcore is no longer a gender issue Is the trend getting ready to jump onto the menswear catwalks?

"He was a punk / She did ballet," sang Avril Lavigne back in 2002, tackling with a worldwide hit a decidedly hot topic for the popular scene at the turn of the century: the rupture between the old and the new, a glaring metaphor illustrating the war between the cool subcultures of the day and ballet dancers. About five years later, a girl with a magnetic gaze and imposing hairstyle roamed the streets of London in her rumpled ballet shoes, pinup tattoos, marked makeup, and skinny jeans. Amy Winehouse, a new soul icon with a cursed soul, was making a name for herself with her poignant music and over-the-top outfits, dictating the canons of a subversive style that mixed fluorescent tops with cuffs and ballet flats. Indie sleaze was a quirky, hyper-sexualizing aesthetic, a trend that idolized skinny bodies and hedonistic living on the edge of excess, but at the same time managed to shake up the crippled fashion system of the 2000s, reawakening interest in certain garments that had fallen into oblivion. This was the origin of balletcore.

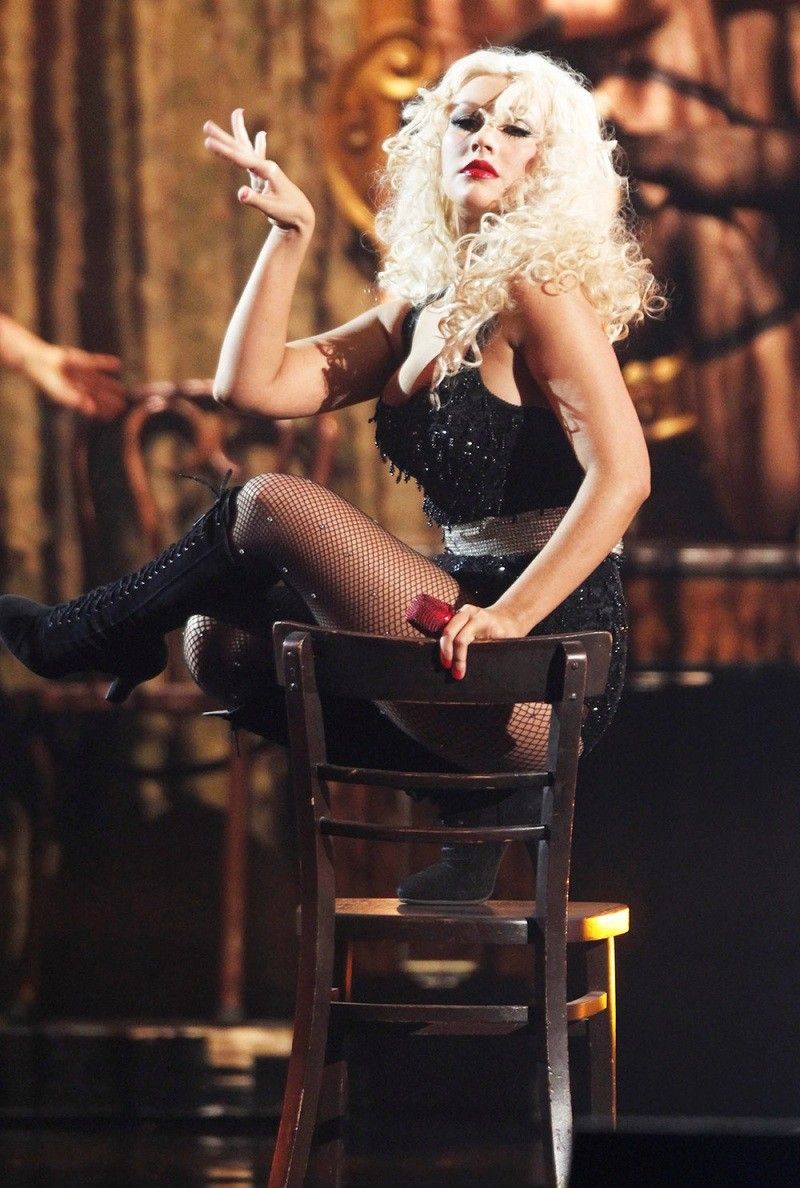

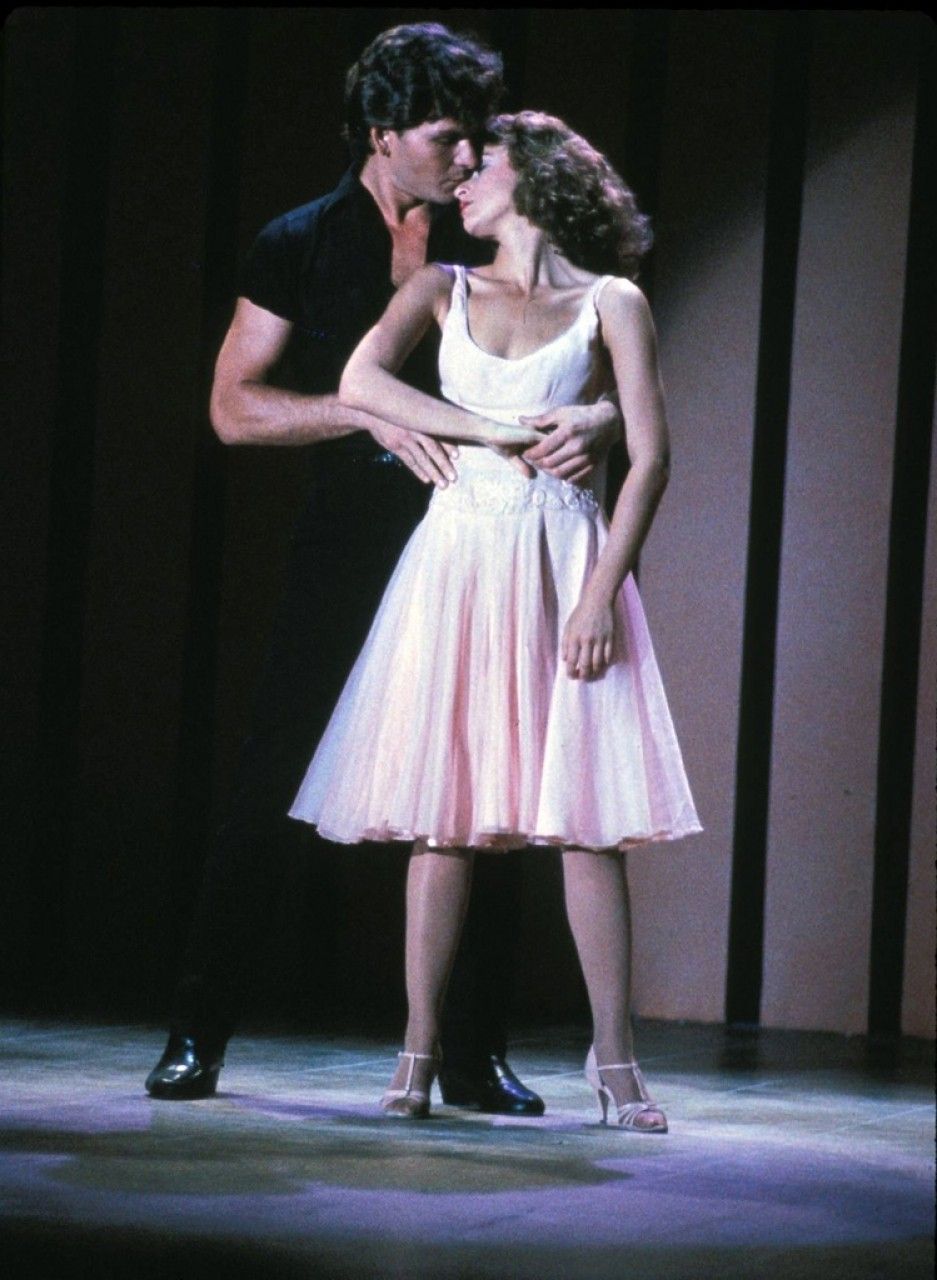

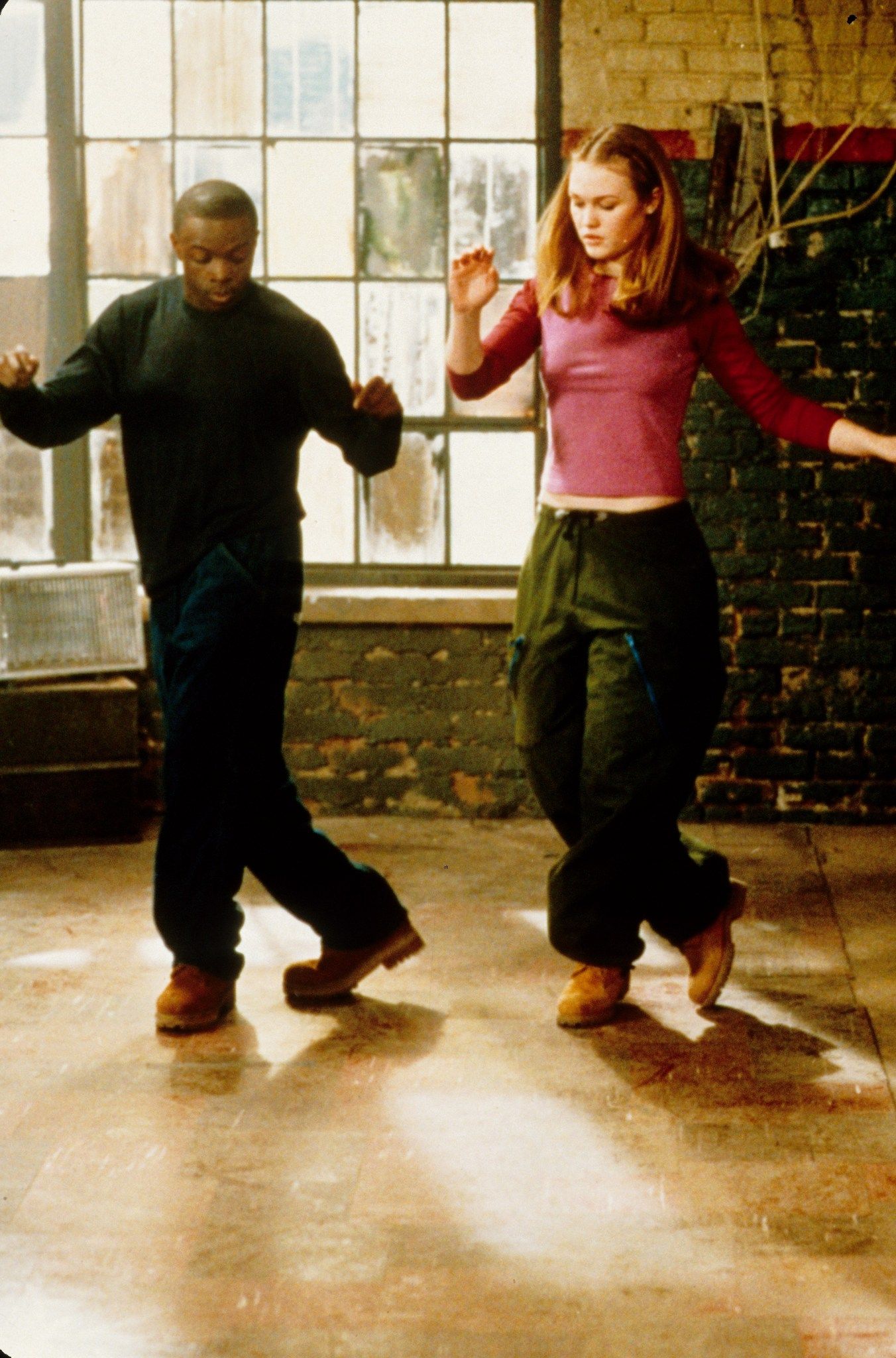

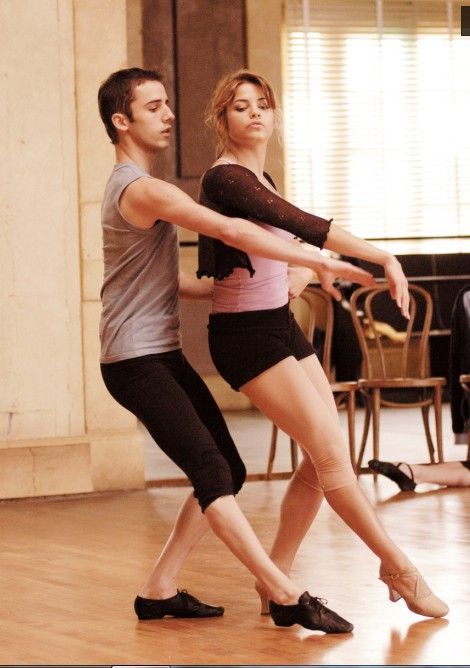

These included all those garments with a distinct femininity that belonged to the sports universe: leggings, leg warmers, cardigans and ballet flats began to take on new meanings through unusual pairings full of contrasts. Dressing as a ballerina and posing as a bad girl had become the latest transgressive trend of the moment, which reached the height of its magnificence in the performances of Natalie Portman in The Black Swan, Jenna Dewan in Step Up, and Christina Aguilera in Burlesque. But if the ballet girls of 2010 exuded femininity and provocation through their skimpy outfits, today balletcore has scattered new trends in its wake with more naïve overtones - such as princesscore and cottagecore - partly abandoning the obsession with lean, athletic bodies. But most importantly, after more than a century, ballet fashion is acquiring more fluid undertones and returning to appeal to male audiences as well.

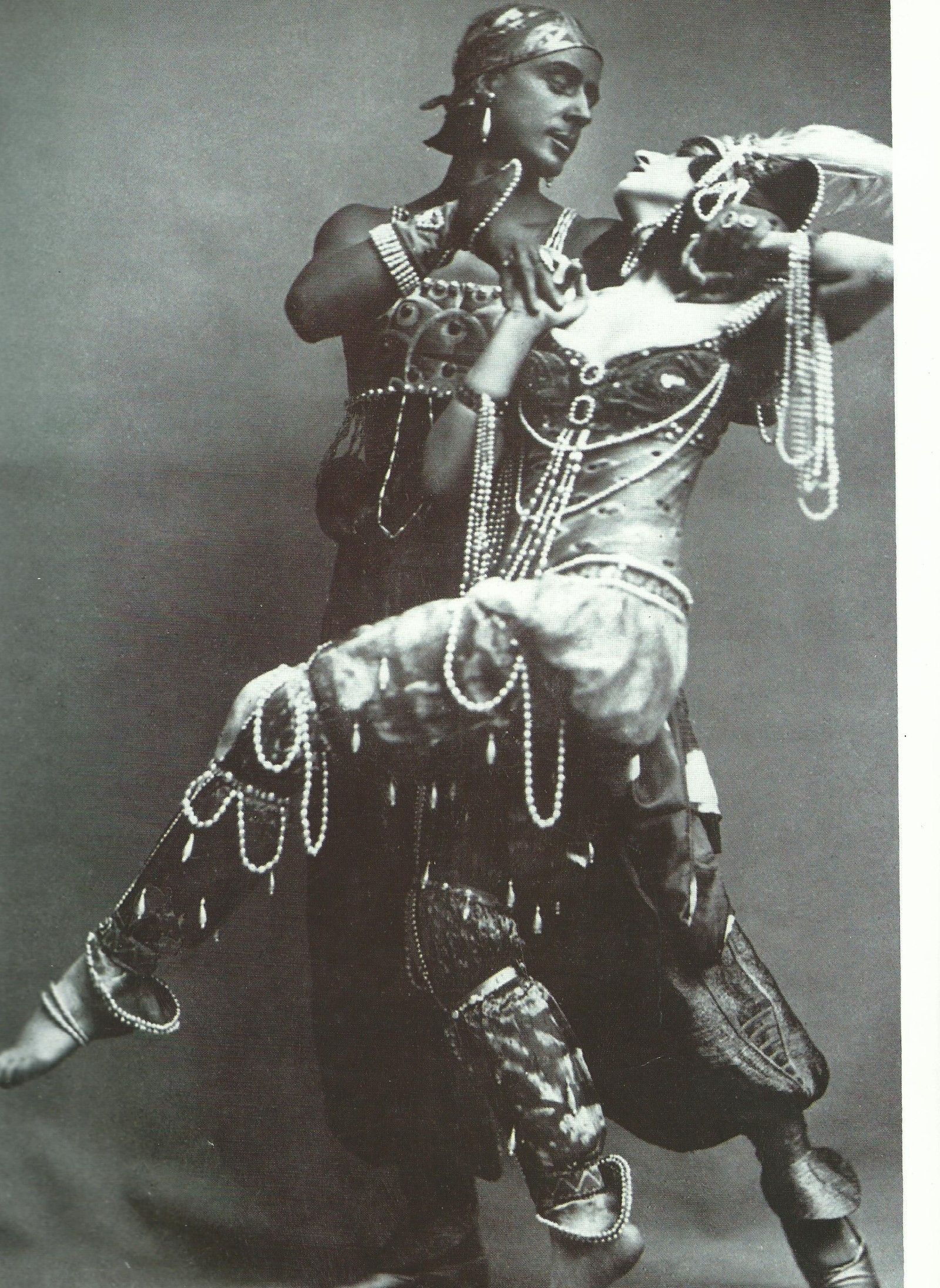

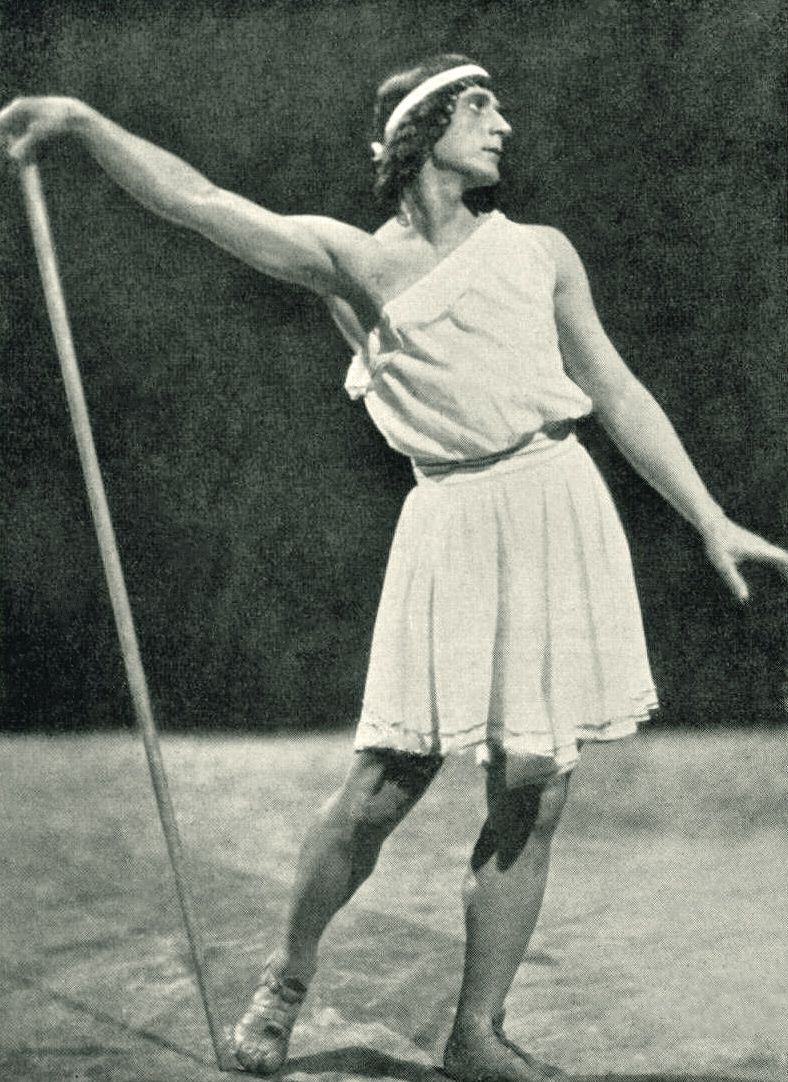

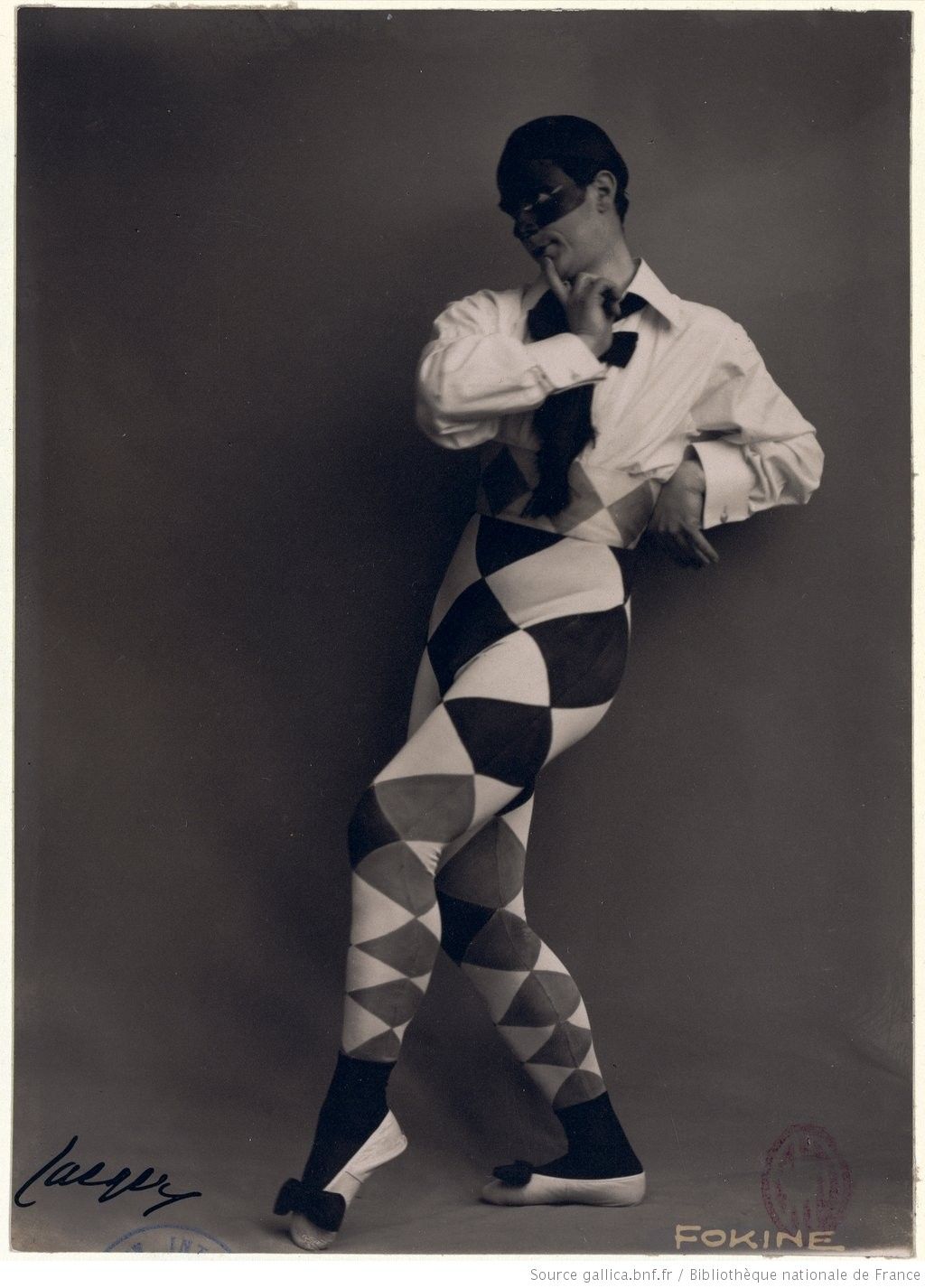

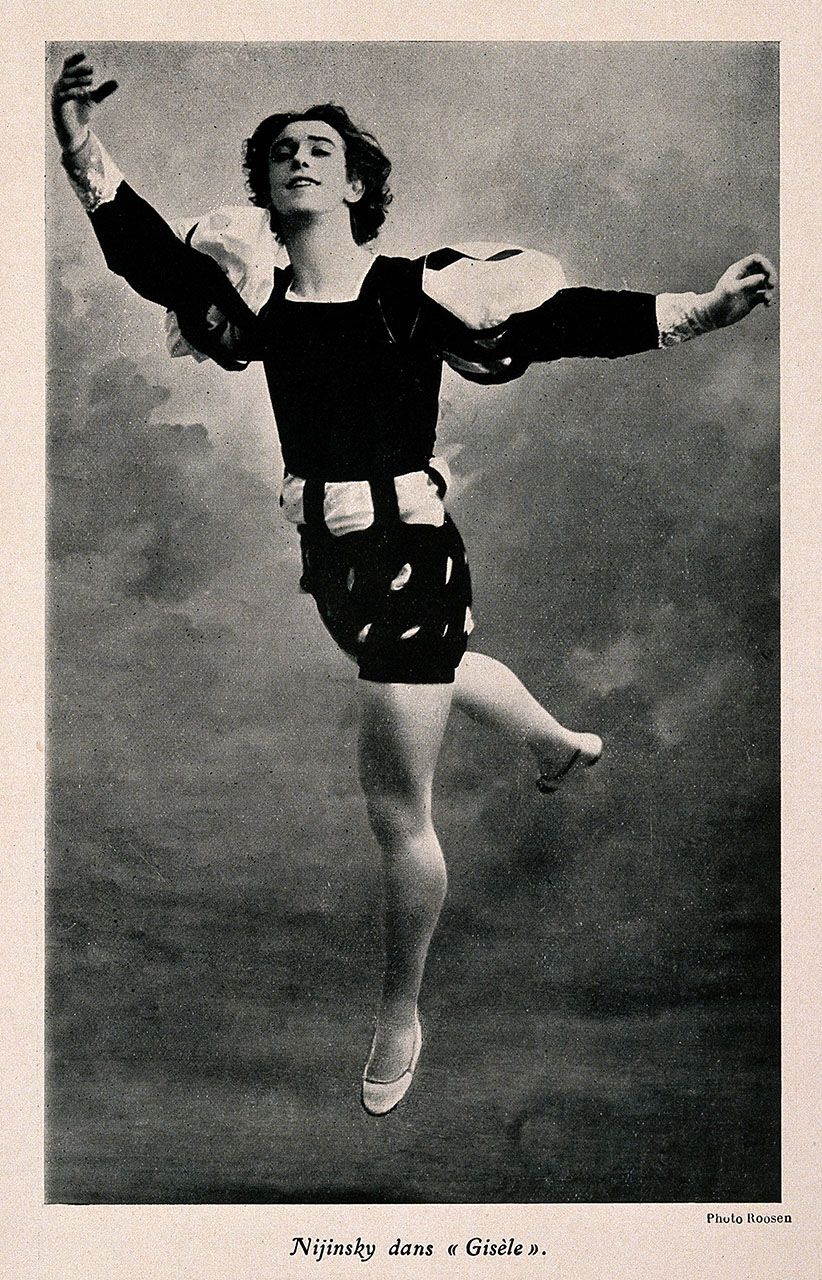

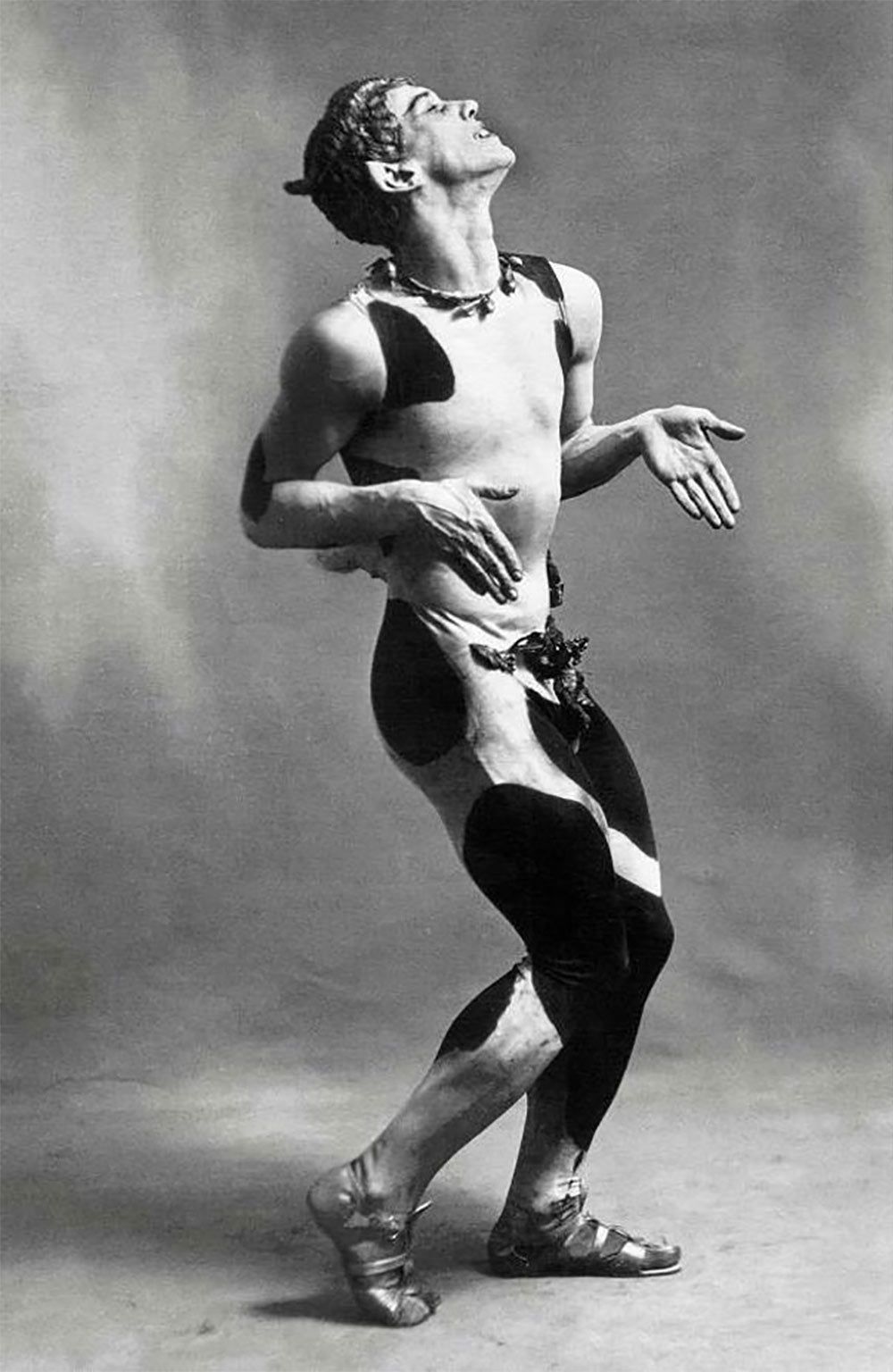

The link between genderfluid fashion and ballet was traced in the early 1900s with Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes, and all those opulent and pharaonic stage dresses created by Paul Poiret, Mariano Fortuny, Pablo Picasso, and Henri Matisse. In the best theaters of Paris, Russian dancers twirled around wrapped in oriental and precious fabrics, bewitching French audiences greedy for aesthetic novelties, who by then, for about a century, had witnessed the metamorphosis of dance into a rigid, classical and purely feminine discipline. But at that moment, the vitality and exotic appeal of the Ballets Russes was peaking with the performances of two charismatic and virtuosic men - Michel Fokine, the first modern dance choreographer in history, and Vaclav Nižinsky, a leading dancer who was often the subject of homosexual scandals. From show to show, the costume designers of the Ballets Russes molded dresses with flowing, soft lines that quickly made inroads even into the women's fashion of the time, which was saturated with all those corsets and padding that imprisoned women in constricting gowns and rigid S-shaped silhouettes. And while Vaclav Nižinsky pirouetted in a tutu covered in bright trimmings and colorful sequins, the Belle Époque gradually abandoned the canons that fashion had imposed in the previous century and opened up to new experiments that favored freedom.

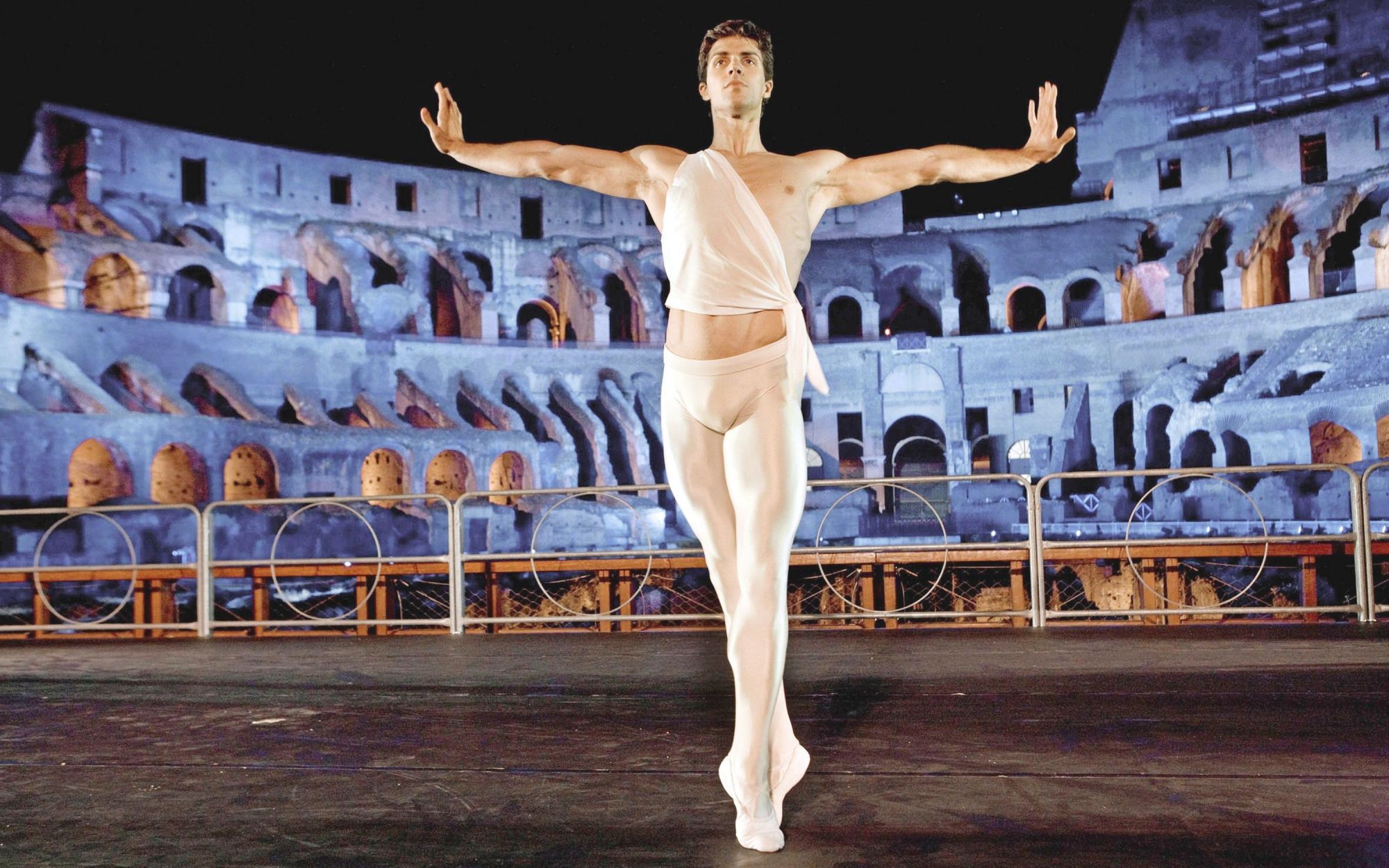

Although the world of ballet, since the Renaissance, has orbited around a male protagonist ("danseur noble"), from the time of the French Revolution to the present day, male dancers have been the victims of growing prejudices that have forced them to perform masculine movements and develop more consistent muscle tone. In addition to this, these gender stereotypes have swept away from male stage costumes of key dance garments, first and foremost, ballerinas. With the exception of such prominent figures as Rudolf Nureyev and, more recently, Sergei Polunin, the figure of the male dancer has become increasingly marginal, and as a result, even high fashion, over the past eighty years, has focused exclusively on the hyper-femininity of ball gowns.

From Dior's famous 1947 cover, which enshrined the ballerina as a female footwear, to Yves Saint Laurent's "Russian Collection" of '76, which brought Russian ballerinas' gowns to the runway, to Viktor & Rolf's SS17 Couture tulle meters and Miu Miu's latest masterpieces in SS22, the dominance of balletcore is still in the hands of women. But in recent years the urgency for freer and more inclusive representation has opened a window for a male balletcore. Primarily Palomo Spain, which brought an inclusive men's collection dedicated to flamenco and Ballets Russes to the New York Fashion Week runway in 2019. In chronological order, however, the record goes to Dries Van Noten, which introduced men's ballet shoes on the runway for its SS15 collection. A few years later it was Gucci's turn and then Jil Sander's , who on their SS16 and SS20 men's runways paired ballet flats with elegant, tailored suits; the trend was not long in coming also to Maison Margiela and Comme Des Garçons, who last fall contributed to the trend with two models of ballet flats, in Tabi and square-toe versions, respectively. But it is only in the last few months that men's balletcore is converging into a concrete reality, mainly thanks to the influence of Harry Styles, who wears a Gucci suit on the cover of Vogue America, and then sported Molly Goddard ballet flats on the cover of his Harry's House album a few months later.

To date, it is still unclear whether balletcore is destined to remain a niche trend, confined to footwear and aimed at the more daring audience, or whether as the years go by, even more traditionalist men will convert to tulle and leg warmers. But glimpses of ballet style appear timidly even on the most recent men's runways, with Fendi's heartwarmers from SS22 or Versace's fluorescent leotards for SS23. So, all we have to do is wait.