Fashion made in the lab Can the future of luxury be cultivated in vitro?

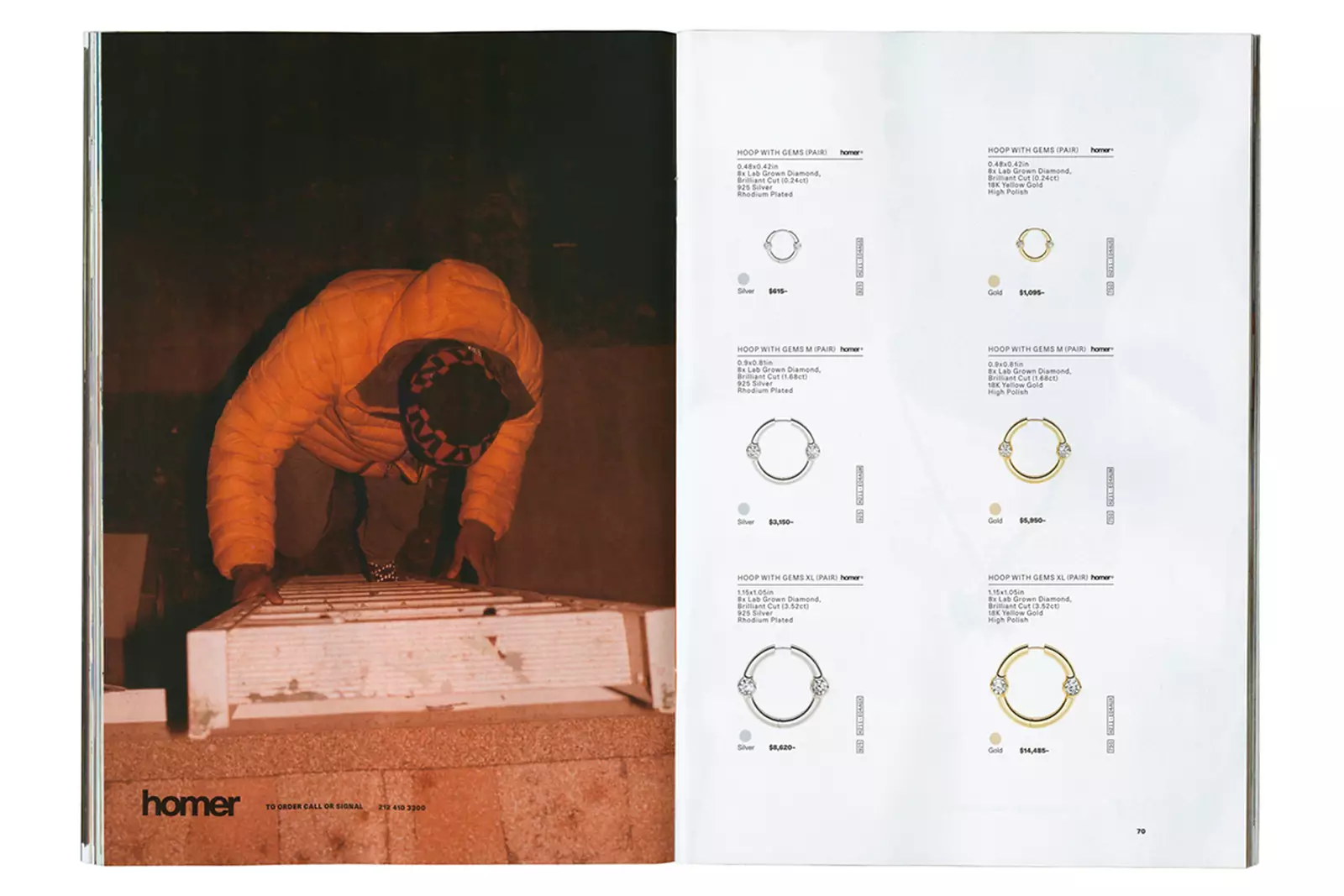

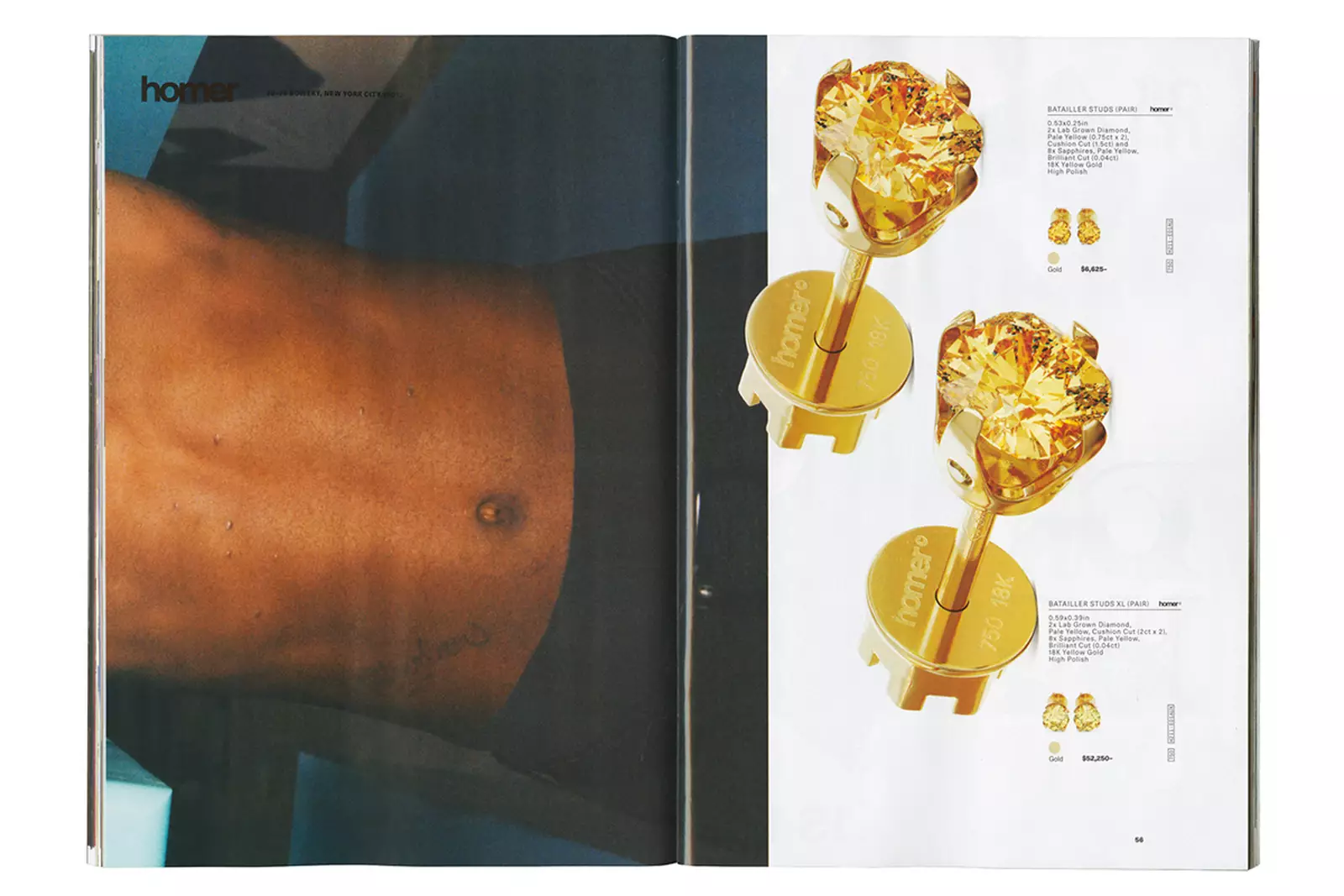

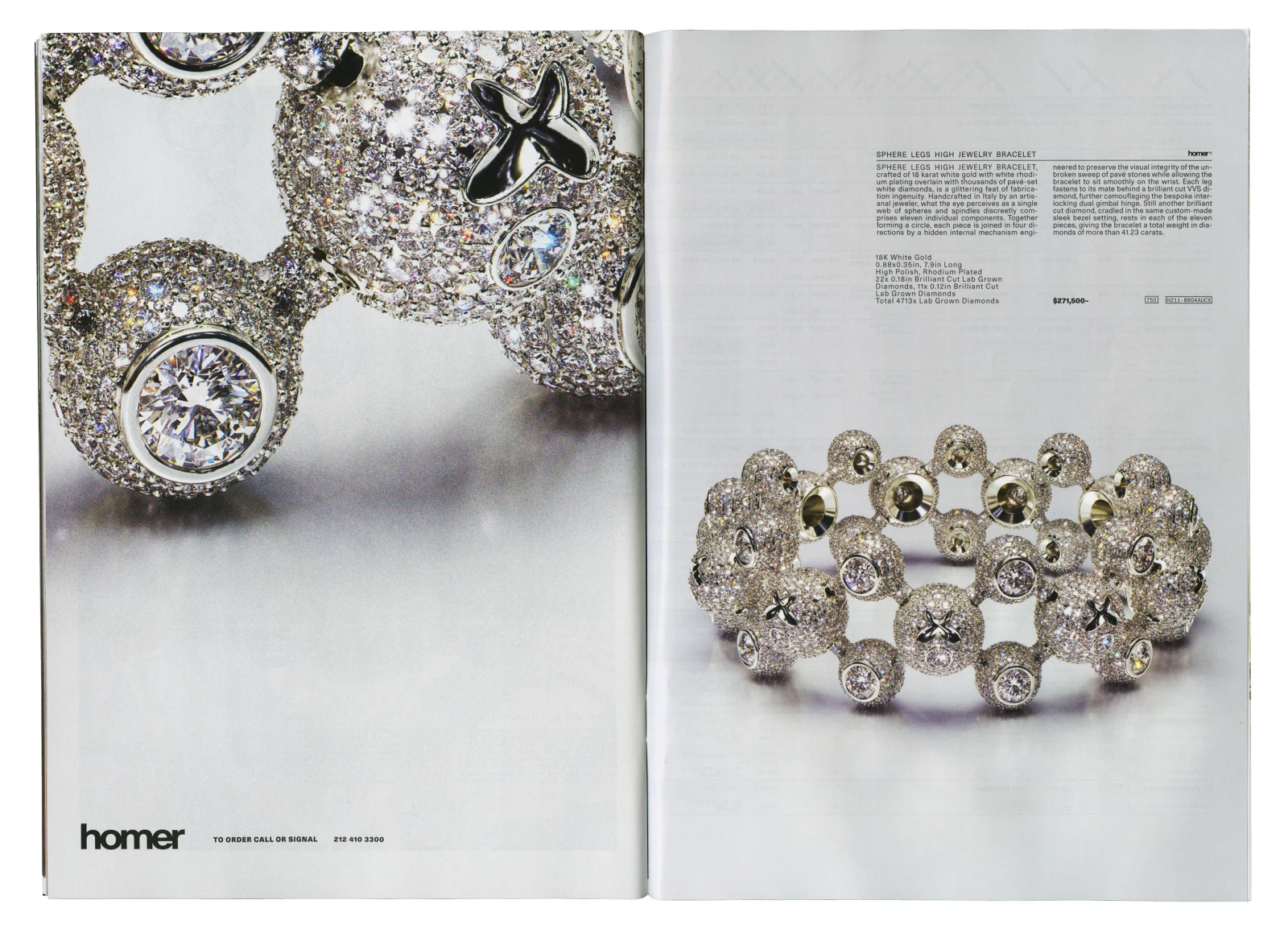

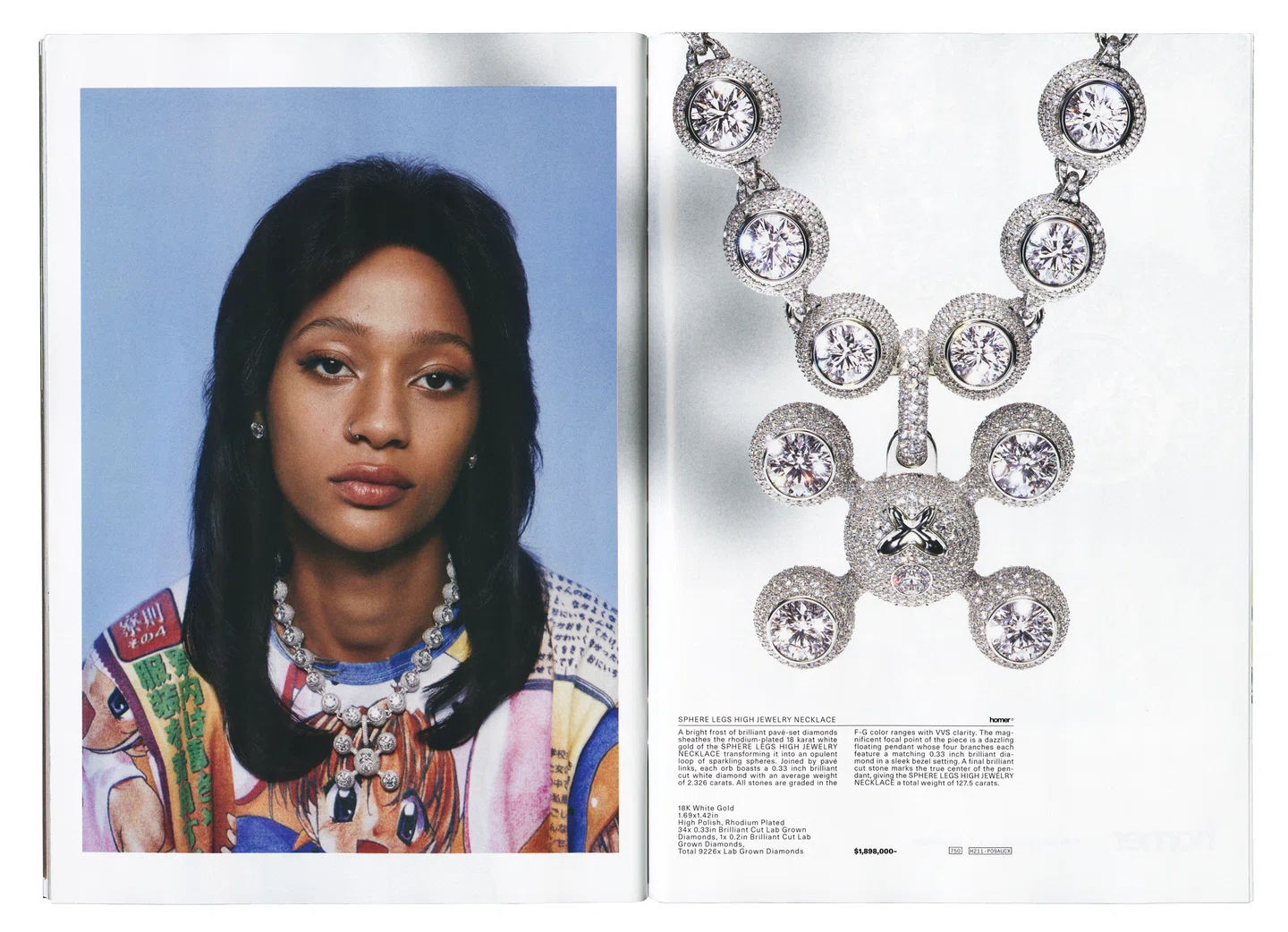

Yesterday, LVMH acquired a minority stake in Israeli lab-grown diamond company Lusix. « the implications of this investment, both for Lusix and for the lab-grown diamond segment, are profound — and so exciting», told to WWD founder and chairman of the company, Benny Landa. In May, however, news broke that both Leonardo DiCaprio and the Kering Group had invested in VitroLabs, a California-based company that produces leather in the laboratory from animal cells that are multiplied in an isolated nutrient-rich environment and, therefore, without killing real animals. Also Kering, along with adidas and Stella McCartney, have invested in Mylo™ Unleather, a leather created from mycelium while already last year Gucci unveiled the first sneakers produced from Demetra, an ultra-circular bio-based material that is expected to replace classic leather. In March last year, on the other hand, Hermès announced an investment in the start-up Mycoworks, which also produces leather from mushrooms, while last August it was Frank Ocean, in launching his Homer brand, who provided the press and the public with detailed documents on how lab-created diamonds were as legit as natural ones. To quote Agatha Christie, To quote Agatha Christie, «two coincidences are a clue, three coincidences are a proof» and luxury's focus on lab-grown materials suggests that the fashion industry's next problem will be to mass-produce and especially legitimize the sale of lab-grown luxury products.

It is clear that what makes products such as diamonds and leather "grown" in the laboratory marketable and recommendable is their sustainability, the innovation they promise, the ultimate redemption they guarantee to a fashion industry that over the past two decades has had to gradually give up the use of the very raw materials on which it had built its prestige: leather, exotic skins, furs, diamonds and gems, and silk. And while it is true that the recovery of these materials is often unethical, especially where fur and diamonds are concerned, it is also true that the traditional paradigm of luxury has been built for centuries on their very rarity and the difficulty of their procurement. But it is clear that in a world where even cotton that is not organic risks being, metaphorically, "bloodied" by ethical concerns or abuses, and where even synthetic fibers must come from recycled plastic bottles and garbage in order not to evoke the image of polluted beaches and agonizing marine wildlife, less problematic and impactful alternatives need to be found for animal skins and diamonds as well. At the same time, for a more traditionalist luxury clientele, it may be difficult to accept that a certain ring or an expensive diamond necklace is to some extent artificial. The same can be said of mushroom-based leather: will the Hermès customer who will be given the option to buy a Birkin be happy to pay 7,000 to 10,000 euros for a non-animal leather bag? And if lab-grown leather products cost less than their leather counterparts, will they be seen as equally prestigious and desirable?

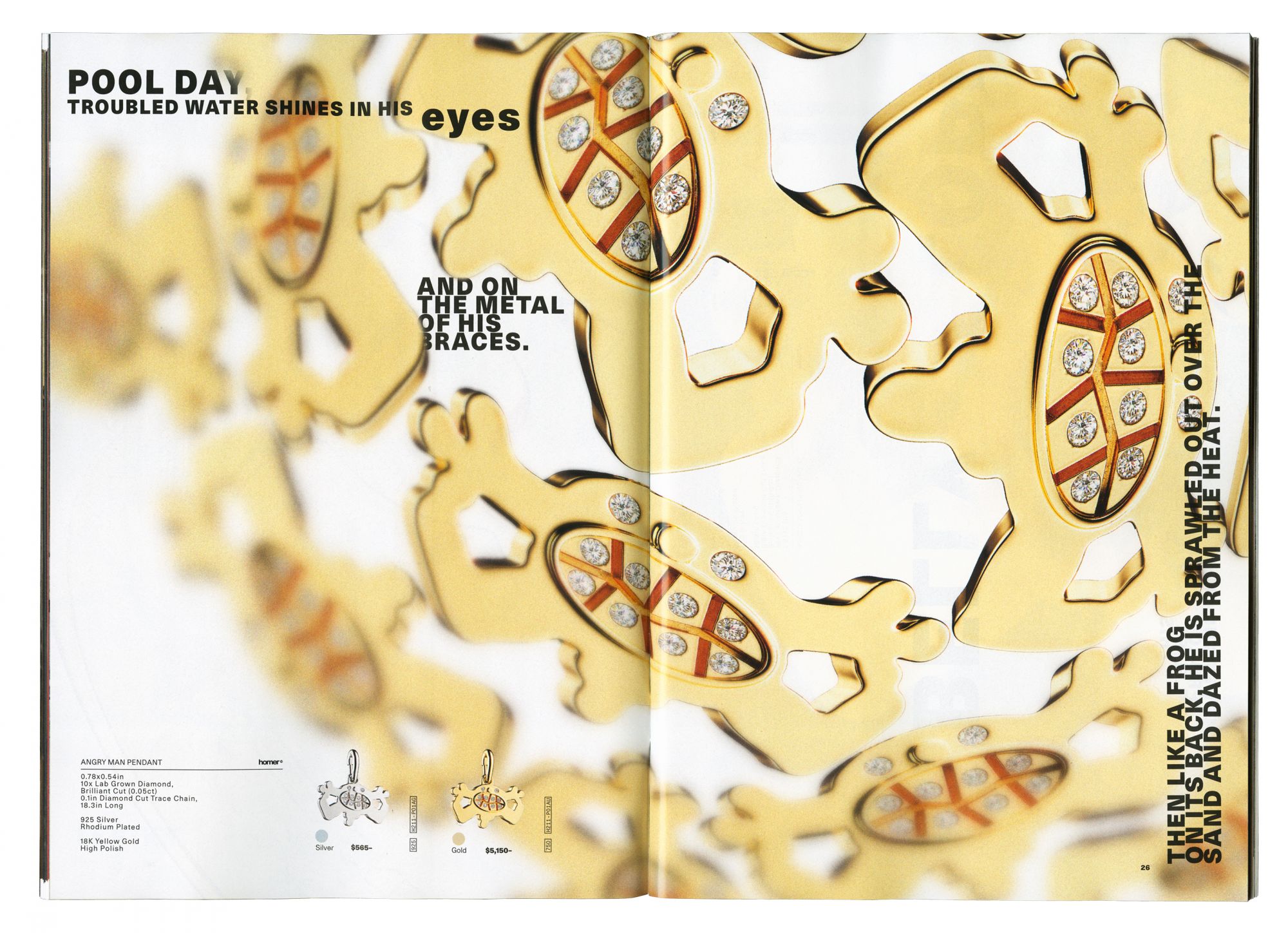

The issue is not secondary. An entire section of Homer's website is devoted to justifying the legitimacy of lab-created diamonds-and it does so in compelling words, too: «the result is the real thing. Not a replica of a diamond, or a close approximation, or a sparkly stone of similar substance. Each diamond is cut, polished, and inspected to meet Homer’s exacting standards before being independently graded by the International Gem Institute. The final product is pure diamond—down to the atoms». Comparing two reports by Bain about the diamond industry in 2019 and in 2021, it is noted that the amount of lab-produced diamonds has not grown year on year, standing at between six and seven million carats. At the same time, however, production capacities are increasing, and the entire segment would appear to be poised to become the truly great alternative for the mass market to traditional diamonds, of which, incidentally, no significant new deposits have been discovered in the past three decades as Forbes wrote a few years ago. In both reports, however, we refer to lab-produced diamonds as an option for the mass market and fashion jewelry - as if to imply that a certain segment positioned very high in the market really does not intend to give up naturally formed diamonds.

Another Bain report for the 2021-2022 notes that «the segment saw continued demand growth and price decreases relative to natural-mined diamonds as lab-grown diamond supply increased and technologies advanced; the average polished lab-grown retail price declined to 30% and the average wholesale price to 14% of natural prices, down from 35% and 20% in 2020, respectively». Leaving the world of jewelry and entering the world of fashion proper, it is safe to say that no special proof is needed on the success of lab-grown and even biodegradable materials: If Bottega Veneta created a hit years ago with its 100 percent biodegradable Puddle Boots, if Balenciaga sent a leather coat down the runway made of Ephea (another name for a type of mushroom-based leather), if Stella McCartney created an entire collection under the Mylo label, and the funding raised by MycoWorks in Series C amounted to $125 million, the market seems to be definitely ready for the arrival of the new sustainable materials, capable not only of making the idea of consumerism more guilt-free but also of being able to be mass-produced, with fewer consequences and, above all, with a more labor- and cost-efficient production model.

Everything seems to point toward a new direction in our perception of luxury. If once the emphasis of the fashion narrative weighed on the rarity, delicacy, and prestige of materials and then shifted toward their performance and sustainability, the idea of a range of laboratory-produced luxury materials hints at a future in which not technical innovation but biotechnical innovation will be the true hallmark of luxury.