What is kidcore? How fashion wants to return to childhood

«Dress up like a grown up» it is a phrase that, in different forms and settings, we have all heard at least once in our lives. And in Italian culture there has always been a precise definition of what it meant to dress "as an adult" and what it was to dress "as a kid". Adults wear the shirt (white or blue) under the pullover, trousers neither too tight nor too wide, preferably leather shoes but, above all, dark colors, with few concessions made to accessories. It is an office outfit, if you will, a uniform that testifies to the degree of personal seriousness of each one within the life of society. Yet, two years ago, society was disrupted by the lockdown and in the general cultural movement that led individuals and societies to re-evaluate their models of life, the need to "dress up" began to fade. Self-expression, gender liberation, end of office life, nostalgia for childhood years, search for simplicity – all possible motivations behind the traction that, in recent months, has gained the kidcore aesthetic that, to quote Lyst, is all about «right colors, toy-inspired accessories, and clashing prints». A type of style that could have its icon in television characters such as Jules in Euphoria or Margot Robbie's Harley Quinn but which actually has numerous variations.

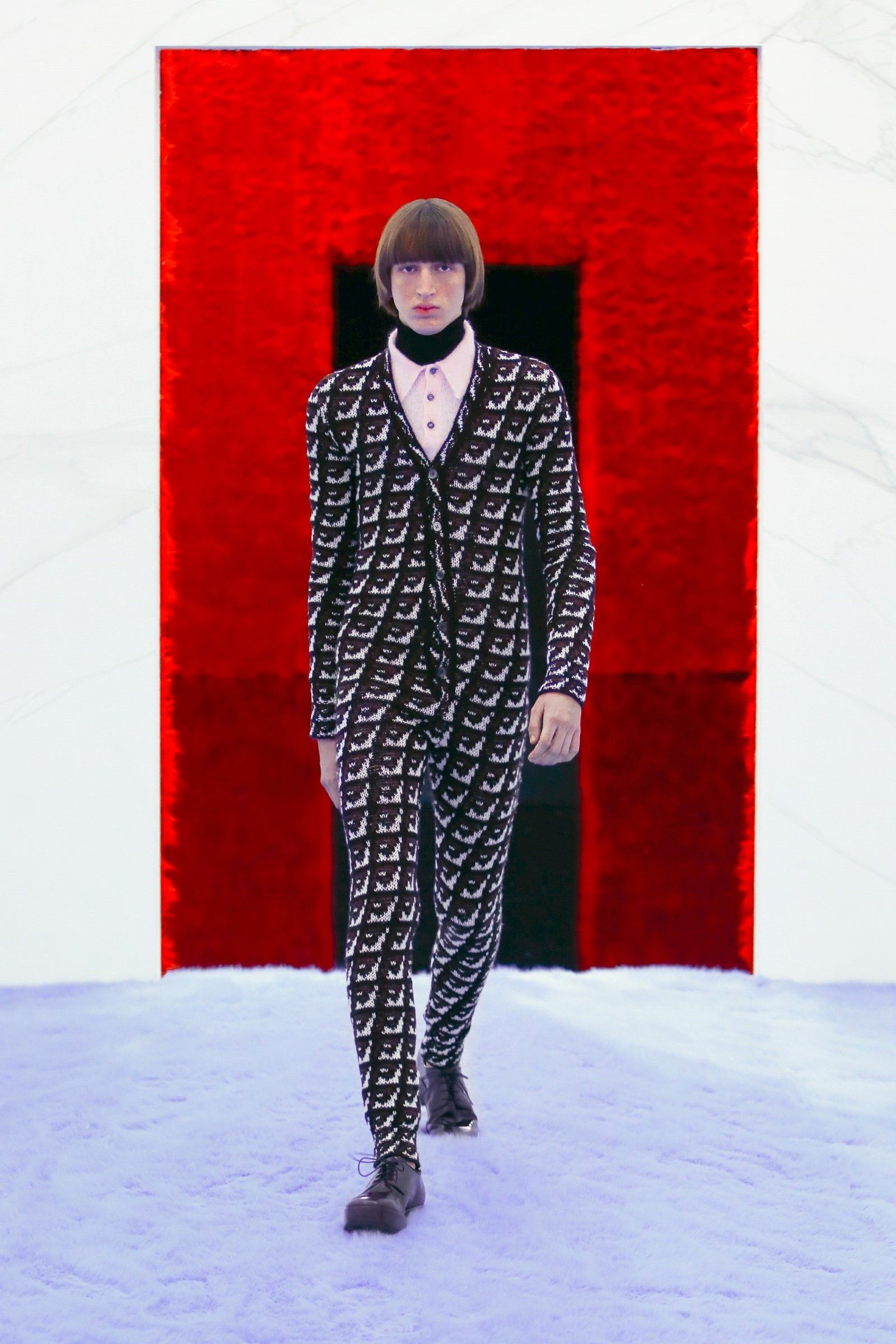

The Mary Jane men's shoes seen on the catwalks of JW Anderson, Fendi and Comme des Garçons Homme Plus this year, for example, are strongly associated with childhood; Anderson's Milanese show, with all the colors, toy-accessories, striped socks and dresses that look soft and colorful like candy was pure, in its own way, an interpretation of the trend – a trend explored, in its visual sides, also by brands such as Blumarine, Undercover, Marni but also Gucci in January 2020. As we said, the possible variations are many: if Gucci's FW20 show evoked childhood but renouncing the maximalism of prints and colors, Jun Takahashi transformed the mecha of Neon Genesis Evangelion into jackets and sweaters while Marni used the naïveté of the contrast between stripes and daisies to convey a more complex message.

Other recent examples: Homer's jewels designed by Frank Ocean are inspired by his «childhood obsessions» while those of Bottega Veneta made with resin beads or in the shape of a telephone cable reminded many of the DIY plastic jewels popular as a children's toy throughout the world; speaking about Prada's long johns presented last year, Raf Simons said he was inspired by cowboy underwear and baby tracksuits; in his SS22 show Marco Rambaldi included kidcore symbols such as butterflies, multicolored prints, drawings of hearts, mesh tops and hair clips transforming them into political statements; Oliver Rousteing has just made Balmain and Barbie collaborate by producing a version of the famous doll dressed in his clothes while in his work at Louis Vuitton, Virgil Abloh has always been refining the concept of boyhood ideology or the idea of adopting the child's gaze without preconceptions. Instead, prophetically, in 2015, Kanye West told Jon Caramanica: «I want to dress like a child as much as possible».

The origin of this style, however, is not TikTok but Japan: it would be impossible not to see a parallelism or at least a kinship between today's kidcore and the concept of kawaii developed in Japan in the 70s and then exploded together with the popularity of the Harajuku style in the 80s and 90s and the fashion lolita documented by the legendary FRUiTS magazine by Shoichi Aoki. If, however, in the case of lolita fashion the quality of cuteness was a part of the Japanese culture of the time, and was affected by historical, linguistic and cultural influences, the kidcore that today has also spread to the West has a strong nostalgic component. Nevertheless, the cultural motivations behind the two aesthetics are similar: reacting to social impositions and adherence to overly defined gender roles, rejecting the social expectations connected to these roles, redefining one's identity as opposed to a series of values in which one does not recognize oneself but also gaining self-confidence and affirming one's ability to express oneself. This cultural ancestry is important because it was precisely with the fashion lolita that the deliberate infantilism in fashion took on a political connotation.

What is more important to note, however, is that the kidcore you see on TikTok, for example in videos where the same person changes his look according to three or four different styles, is an extremely "pure" and somewhat fictitious version of itself and that, within a fashion collection for example, it always ends up diluting and attenuating but still remains recognizable in the form of a sort of naïveté, of apparent simplification of shapes, volumes or graphics, of extreme stylization or, on the contrary, by an exaggeration of colors and textures that replicates the liveliness and play of childhood. At the base, there are always the values of simplicity and frankness – yet another search for authenticity and reality of an industry and a culture that have explored everything explorable.