The fashion industry looks more and more like Silicon Valley The policy of the wild acquisitions of luxury mega-groups is increasingly similar to that of Google and Meta

On January 18, the acquisition of a minority stake in Aime Leon Dore by the LVMH group was announced, the flagship of a round of investments and acquisitions started in 2019 with Gabriela Hearst and which today counts the beauty brand Versed, the streetwear brand Madhappy and, among others, also the English start-up Heat that deals with mystery boxes while the various companies and funds linked to LVMH have acquired over time Tiffany & Co. but also shares in Etro, Off-White and in the new brand of Phoebe Philo but has also increased its shares in Emilio Pucci and Tod's. LVMH's spree shopping was perhaps the most striking series of acquisitions and expansions of 2021 - a year that has seen important maneuvers such as the acquisition of Stone Island by Moncler, that of Jil Sander by the OTB group and that of Supreme by VF Group while other brands such as Prada, Zegna and Chanel have centralized control of the supply chain by acquiring their suppliers. Beyond the various meanings of these acquisitions, there is a prevailing pattern on the part of luxury conglomerates that consists in expanding by incorporating smaller and more independent realities and leaving fewer and fewer competitors in the field – a pattern that would seem to mimic that of Silicon Valley companies that, as reported by the Financial Times, «have snapped up smaller rivals at a record pace this year […]. Data from Refinitiv analysed by the Financial Times show that tech companies have spent at least $264bn buying up potential rivals worth less than $1bn since the start of 2021».

A model, that of companies like Meta or Google, which has actually worked financially over the years but which has often been questioned for the overwhelming power that those same companies had begun to hold – especially with regard to the use of user data. In fashion things are different, no less, however, a market in which independent brands are forced to face the giants of luxury is necessarily an unbalanced market – especially since this competition puts independent brands in a position to be acquired. Just as in the tech world many app or service founders aim to expand their business just to be able to sell it (following the famous example of Tom Anderson who, after co-creating MySpace, sold everything in 2005 and left with 580 million dollars in his pocket), there is a risk that new independent designers in the world of fashion or streetwear will begin to found new brands or retail models with the ultimate goal to associate with a large luxury group, obtaining an important commercial validation but also logistics and production platforms on a global scale.

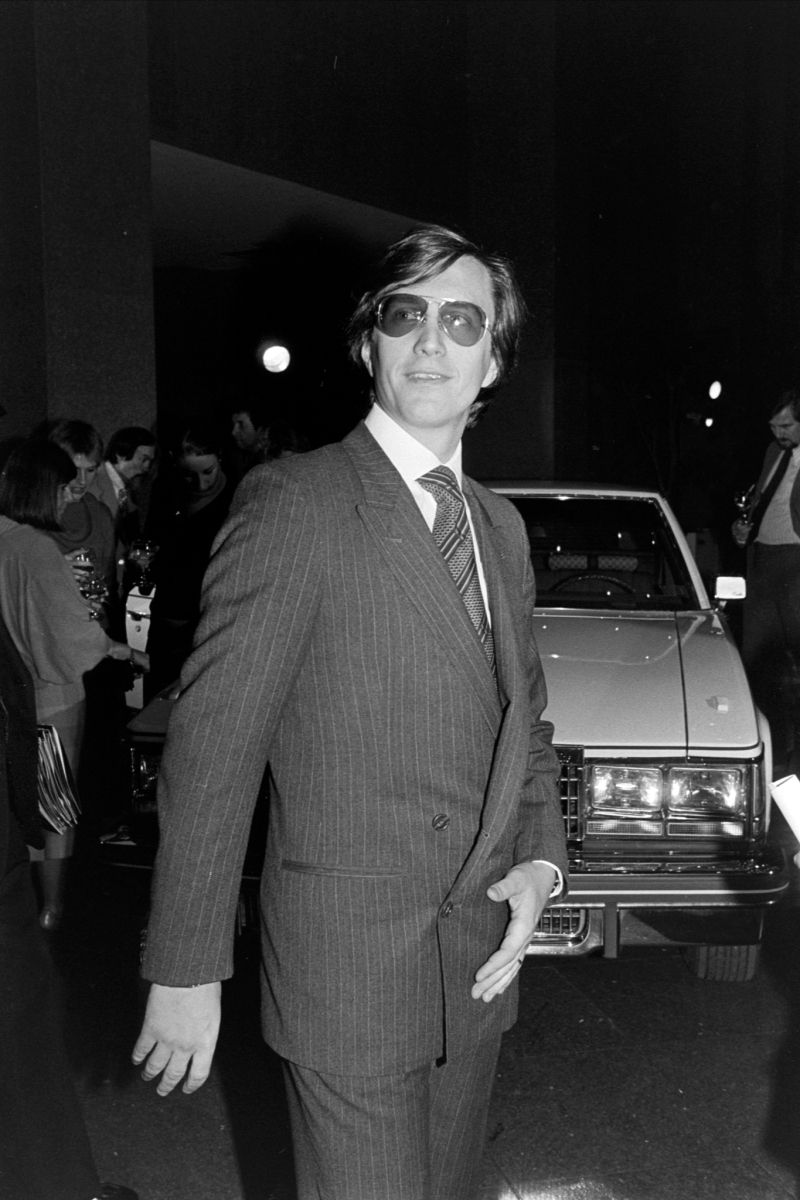

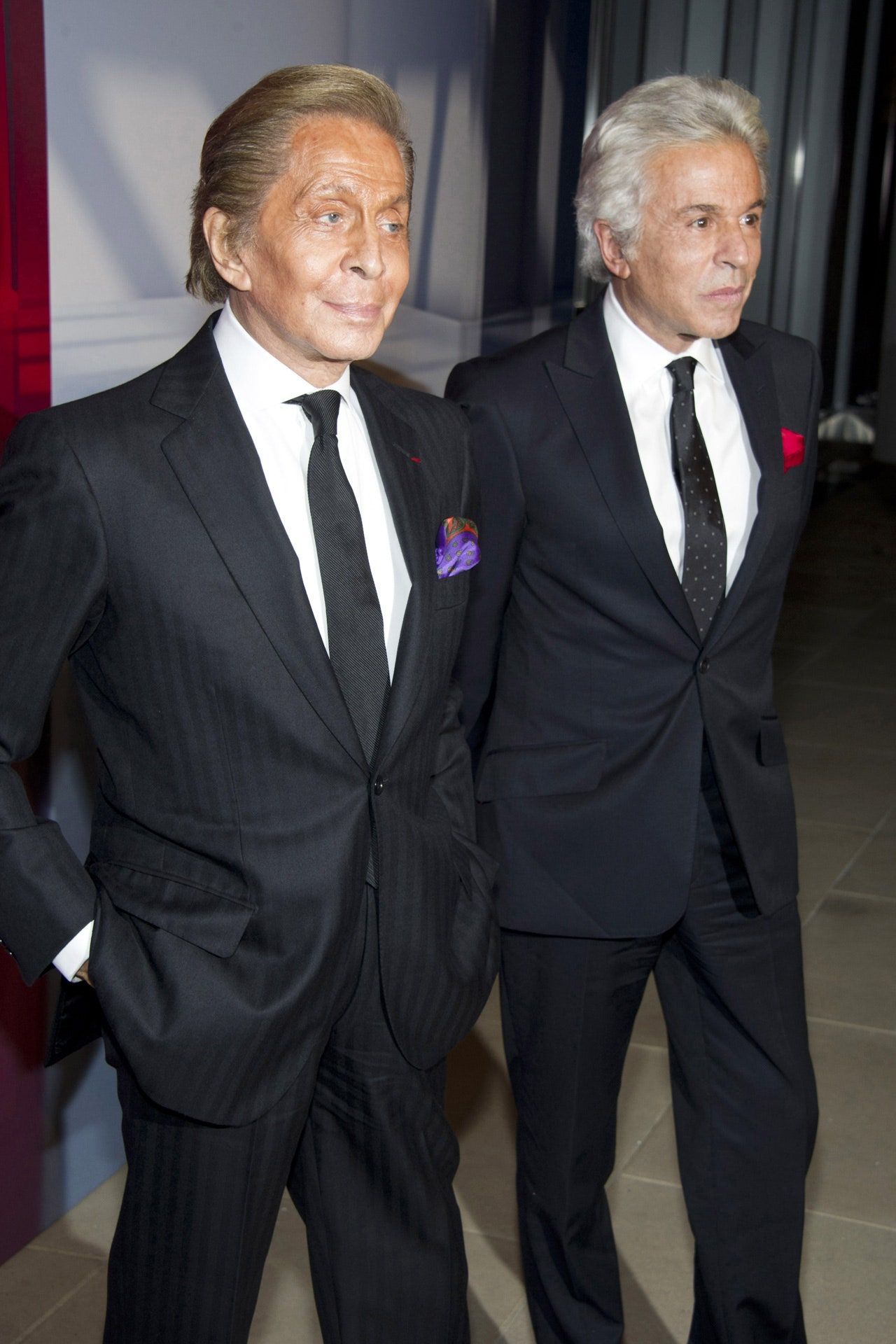

In the fashion world, however, selling his company while maintaining creative control is nothing new: in '93, Maurizio Gucci sold the family business to Investcorp for 170 million dollars after having almost bankrupted it and exiting it definitively; in '98 Valentino Garavani and Giancarlo Giammetti sold the brand for 300 million dollars to a conglomerate of the Agnelli family even if the designer remained at the creative helm of the brand until 2007; more recently the Versace family sold the eponymous brand to Capri Holdings for 1.8 billion euros, investing in turn 150 million euros in the shares of the conglomerate and always leaving Donatella Versace in the role of Chief Creative Officer and Carlo Rivetti sold Stone Island to Moncler for 1.15 billion euros, leaving Carlo Rivetti the role of president and creative director. In these and other cases the sale concerned either a cashout of the owners who abandoned the metaphorical ship or a matter of growth: Rivetti defined the acquisition by Moncler as a way «to face united, and stronger, the challenges that await us» while Donatella Versace sold the company to help it «reach its full potential».

Just like Versace and Stone Island, Aimè Leon Dore has maintained its creative independence and will use LVMH's platform to expand its retail presence – nevertheless it is useless to hide that the luxury industry, with a few exceptions, is practically an oligopoly dominated by large corporations and that this does not escape consumers, especially to the communities of cult brands such as Aimè Leon Dore, leading them to worry about how the new chain of command will affect the authenticity of the brand. This is a very important point as in recent years brands have had «the opportunity to move beyond running clubs and yoga classes, and become global “brand-nations,” filling the void in values, in meaning, in belonging that has been left by government and religion, and recruiting millions of followers in the process.»,as Doug Stephens wrote some years ago on Business of Fashion.

This means that the success of a brand is determined by its skill in community building and depends to some extent on the maintenance of that community. Speech that brings into play the realness of fashion – that is, the ability of a brand to convey to its followers a sense of authenticity and integrity first of all aesthetic and creative and then value-related. By acquiring successful independent brands, the big luxury groups aim to acquire their cool factor and their communities – but it is up to them to maintain that cool factor by enriching the brand's universe without crushing it under the weight of corporate practices and company directives.