How long do creative directors last? 5 years might be the most successful timeframe for a designer leading a fashion house

There is an expression that, more than any other in recent years, has come to define the continuous changes at the top of the fashion houses. The so-called 'game of chairs' has become the most appropriate definition to describe the evolution of creative direction in recent years, reflecting a practice that has become consolidated within the fashion system, accustomed to traveling at a very fast pace, relying on equally short cycles. In this regard, a report published by the analysis firm Bernstein, reported by Quartz, is very striking. It analyzed the performance, share prices and enterprise value of several fashion brands in relation to sales. What Bernstein has identified is a time frame of 5 years from the installation of a new creative director in which there is a significant increase in sales, and after a period of adjustment, the beginning of a slow decline. Five years would thus seem to be the maximum time in which to identify the rise and fall of a new creative director.

Before continuing, it should be noted that Bernstein's report examined the case of 18 different creative directors, without taking into account the relationship between creative directors and source of income; nevertheless, the report gives a faithful portrait of today's industry, which has become a slave to the concept of novelty. Never as in recent years has the fashion industry in its entirety adopted methods and practices typical of the streetwear world, first and foremost the concept of hype, building its charm and strength on the constant search for the next big thing. Ultimately, it is the novelty that fuels sales.

The search for novelty

To that anticipation, to that sometimes hysterical wait, contributes an important factor to be taken into consideration. Nothing attracts more attention, creates more expectation than a designer called upon to revive the fortunes of a moribund brand or one with a very long history, even more so if that designer does not belong to that world. This was the case in the months leading up to the first fashion show of Riccardo Tisci at Burberry, a creative with a background and past experience clearly distant from the heritage and English tradition of a brand like Burberry. But even more so was this the case with Louis Vuitton and Virgil Abloh. Forgetting for a moment the historical significance of this appointment, and the buzz that the first rainbow fashion show had generated, there is a very interesting fact: in January 2019, in the pop-up of the French brand in Tokyo, in the first 48 hours the brand had recorded more sales than those of the collaboration with Supreme, a testament to how much Abloh had created interest in the brand.

The most exemplary case of the time line traced by Bernstein is certainly Gucci, under the creative direction of Alessandro Michele. With the arrival of the Roman designer, Gucci has experienced exponential growth, becoming the most important brand in Kering's portfolio. Arriving at the helm of the historic Florentine name almost as a complete stranger, Michele had the merit of having created, from his first collection, a new, original aesthetic, completely different from that to which Gucci consumers were accustomed, finding in this the key to his success. There is also another element not to be forgotten. The great and historic luxury fashion houses do not make a profit on the sale of their clothes, especially those seen on the catwalk, as much as they are totally dependent on the sale of accessories, leather goods, perfumes and cosmetics, products that are more accessible to a wider public than creations with exclusive prices.

The three-year club

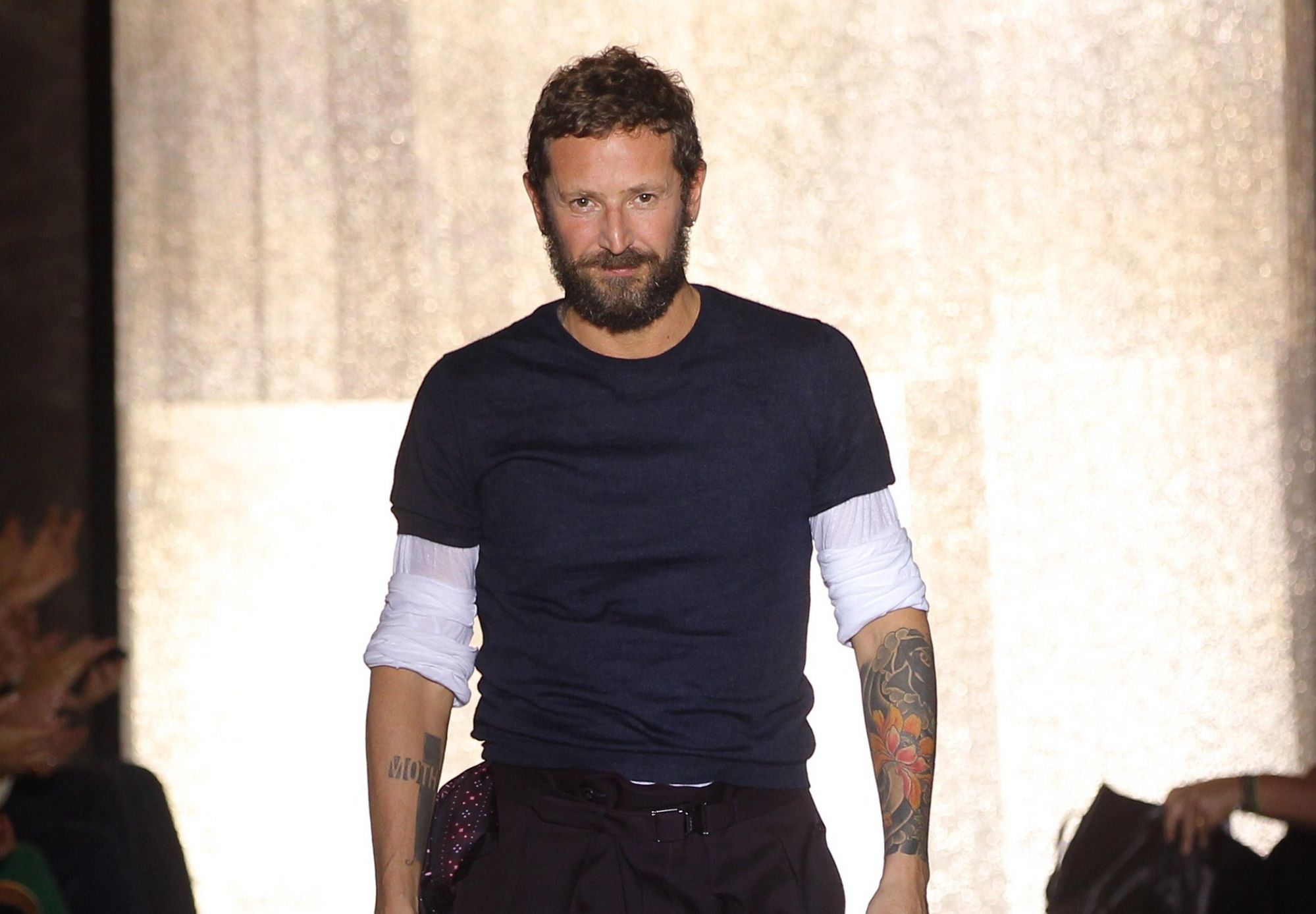

It is for this reason that despite the ups and downs, the alternating success of collections, and more or less positive criticism, the big brands that can rely on their hero products, whether it be a best-selling bag or a perfume that has become a classic, will be less and less affected by changes at the top. These staple products act as a sort of buffer, absorbing shocks and slumps, and in fact forming a solid base on which the brand can dare and experiment without risking too much. In this sense, the leadership of Bottega Veneta under Daniel Lee has been exemplary of how a brand can regain its strength thanks to a series of products that are not linked to ready-to-wear, iconic products that have become key elements of the three years of the British designer at the court of Bottega.

The news of the separation between Lee and the brand linked to the Kering group is part of the three-year group, that set of more or less relevant designers who have said goodbye well before the aforementioned five-year parabola. Excellencies such as Raf Simons, who left Dior in October 2015, Hedi Slimane, who said goodbye to Saint Laurent in April 2016, and Stefano Pilati, who said goodbye to Ermenegildo Zegna in February 2016, are part of this group. Often heavy work rhythms and creative differences are often among the major causes of these early farewells, a perfect example of a fashion system that is all too hyperactive and often impatient in the search for results.