Can Sanremo really represent the country? More Mahmood and less Iva Zanicchi

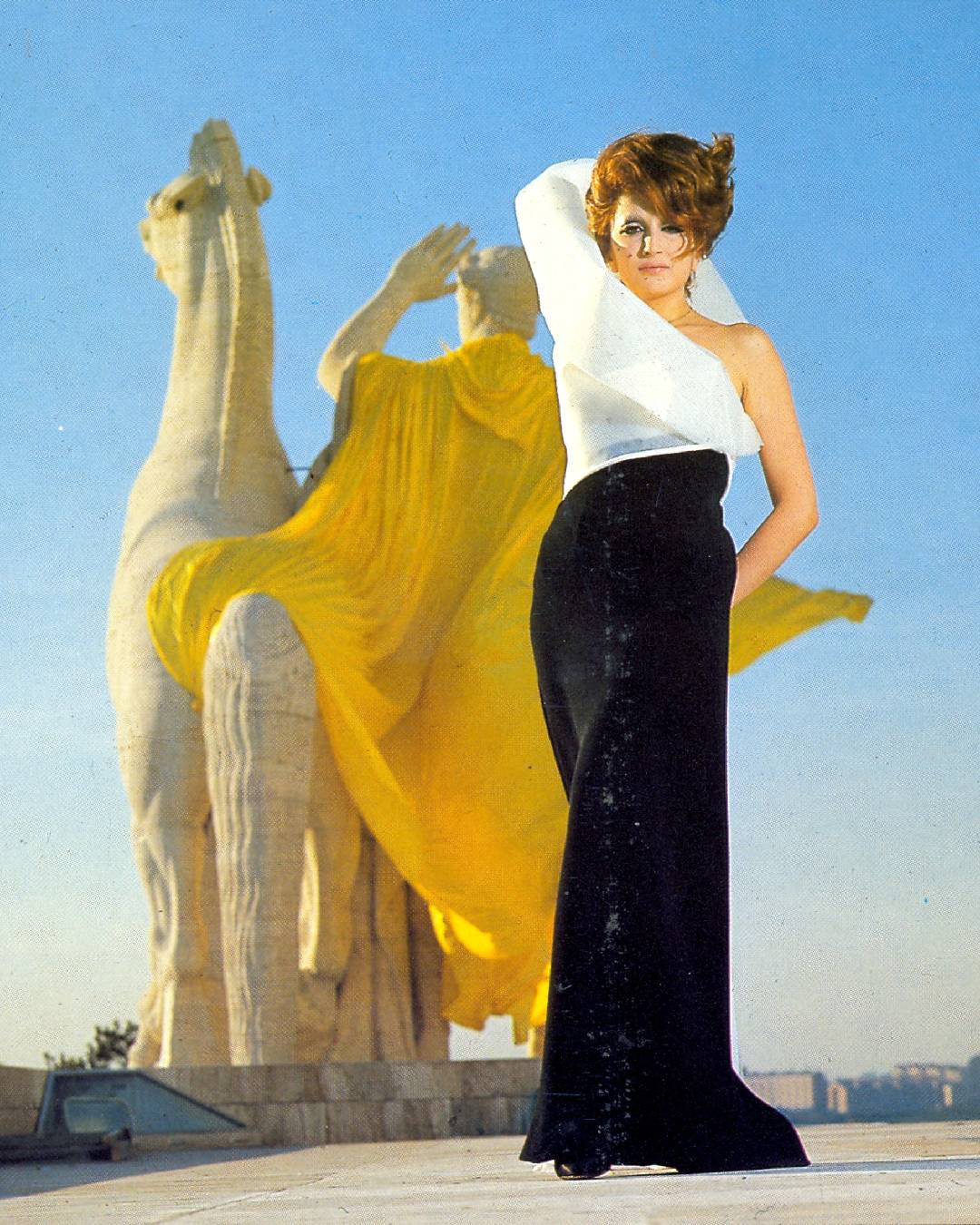

A companion of most of the Italian public, the Sanremo Festival has become a staple of Italian culture, transforming itself year after year more and more into a mirror of our society, but above all of its inability to create and carry out a pop culture worthy of being called such. The problem between pop culture and our country is now well known, which has its roots in a concept of provincial and national-popular show passed from Festivalbar to Telegatto with few flashes and attempts to create a product not only exportable and enjoyable abroad but also not intrinsically linked to the idea of a country of "pizza and mandolin". In spite of the morbid relationship with which a good part of Italians live the approach of the Festival and its evenings, probably none of us follows it for the pleasure of watching a qualitatively satisfying program, but probably is moved by a personal attachment to an institution that has become irreplaceable in our TV.

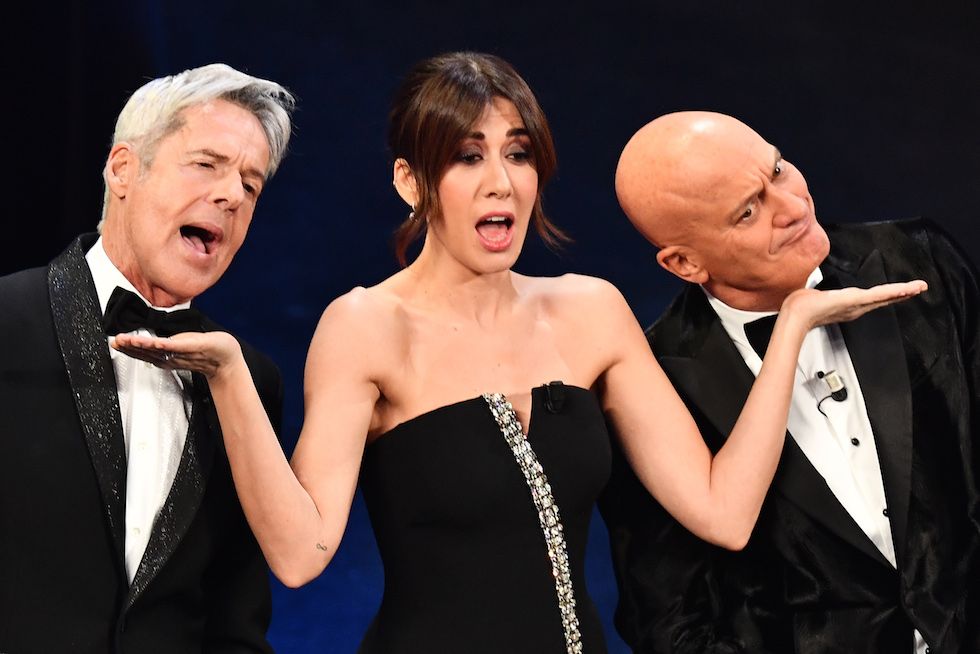

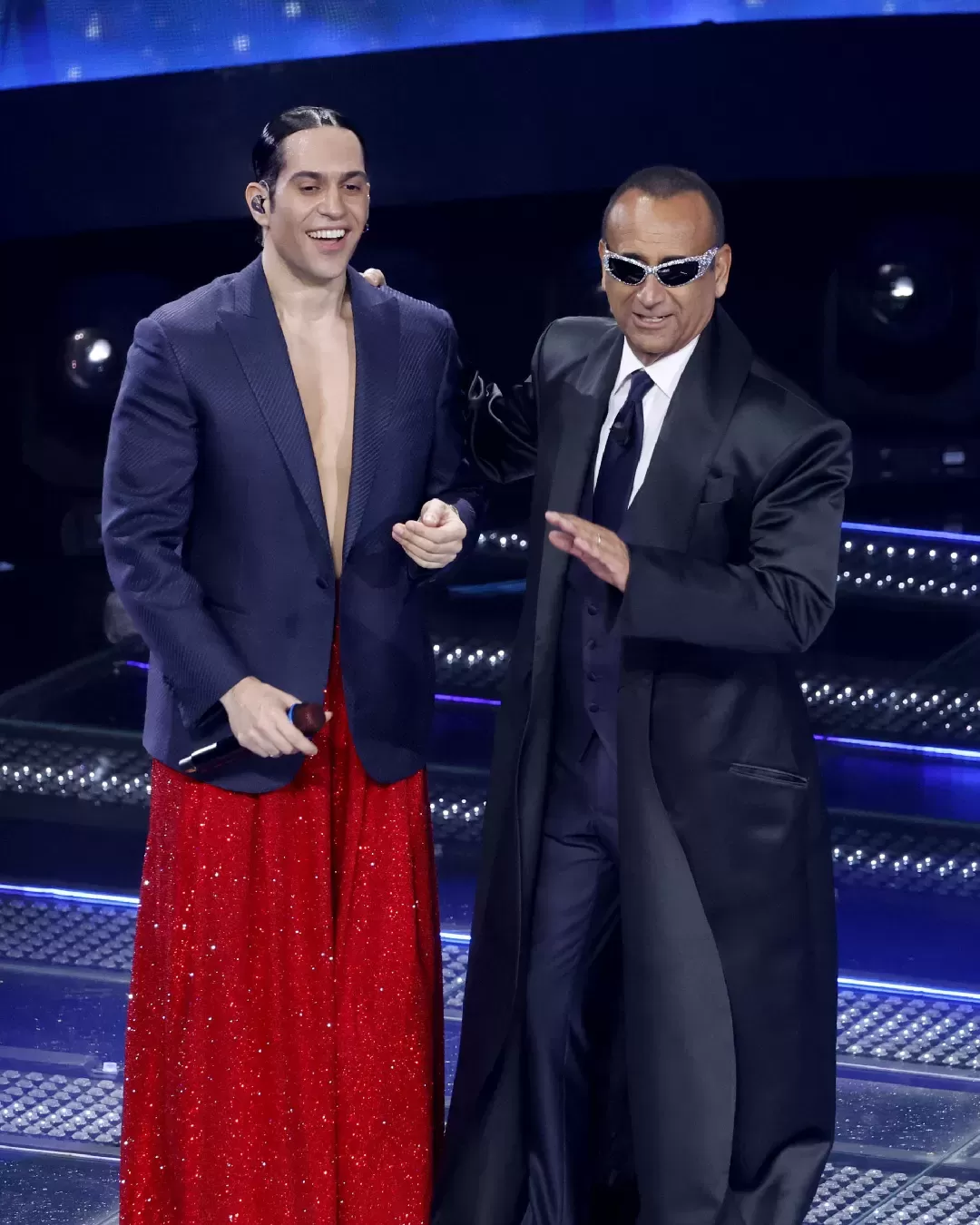

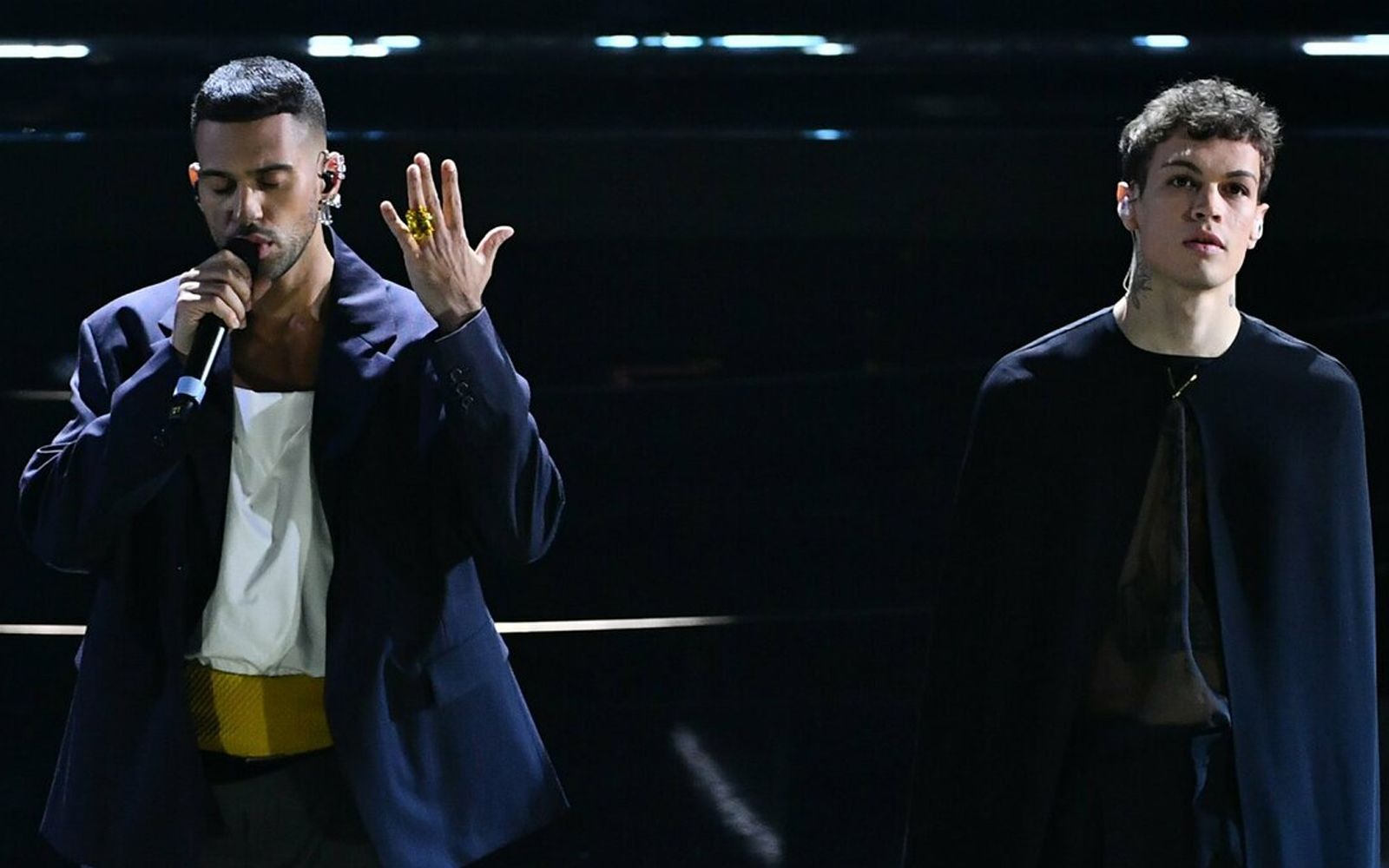

Despite the defeatism, another Sanremo is possible. Above all, a different Sanremo is possible. In recent years, the world of fashion has certainly brought a breath of fresh air to a format that was beginning to smell stale, but above all that was not able to dialogue with other areas that were not those of the musical microcosm. In this sense, the slow but effective generational change of the names on stage has led during the last editions to put more attention on the styling of the artists, bringing to the Sanremo Festival that more "fashion" component that we have always envied, and certainly appreciated, to events such as the Oscars or the Met Gala. Aiming at Sanremo as a springboard to relaunch pop culture in Italy seems a natural consequence given the absence of other events capable of exerting the same charm of the Festival. Years ago an attempt of this kind was made with the David, the Italian film awards that in their short-lived management by Sky became distant relatives of the Oscars; but after that praiseworthy attempt, the destiny of pop appointments in Italy remains solely in the hands of the Italian Song Festival.

But in order to change Sanremo, to make it a mirror of the country 2.0, a real step forward is needed, an approach towards the generation that will be watching Sanremo for the next twenty, if not thirty years. Because if the more adult audience lives the Festival with a bond born with Pippo Baudo and the Jalisse, the younger one needs to create a personal connection through an aging of the Festival, something that perhaps is difficult to combine with the constant presence of Amadeus and Fiorello. Something similar was done in 2020, when the DopoFestival went from the classic live on Rai1 to streaming on RaiPlay in an attempt to take advantage of the Netflix wave and giving the reins of the program to names like Myss Keta and Valerio Lundini. But is it really enough? If Sanremo is a product of Italian pop culture, then the problem lies at the base, in the need to change the way we do and see not only TV, but also the way it connects with the outside world.