What's missing in "The Social Dilemma"? All the omissions and simplifications that the Netflix documentary doesn't talk about

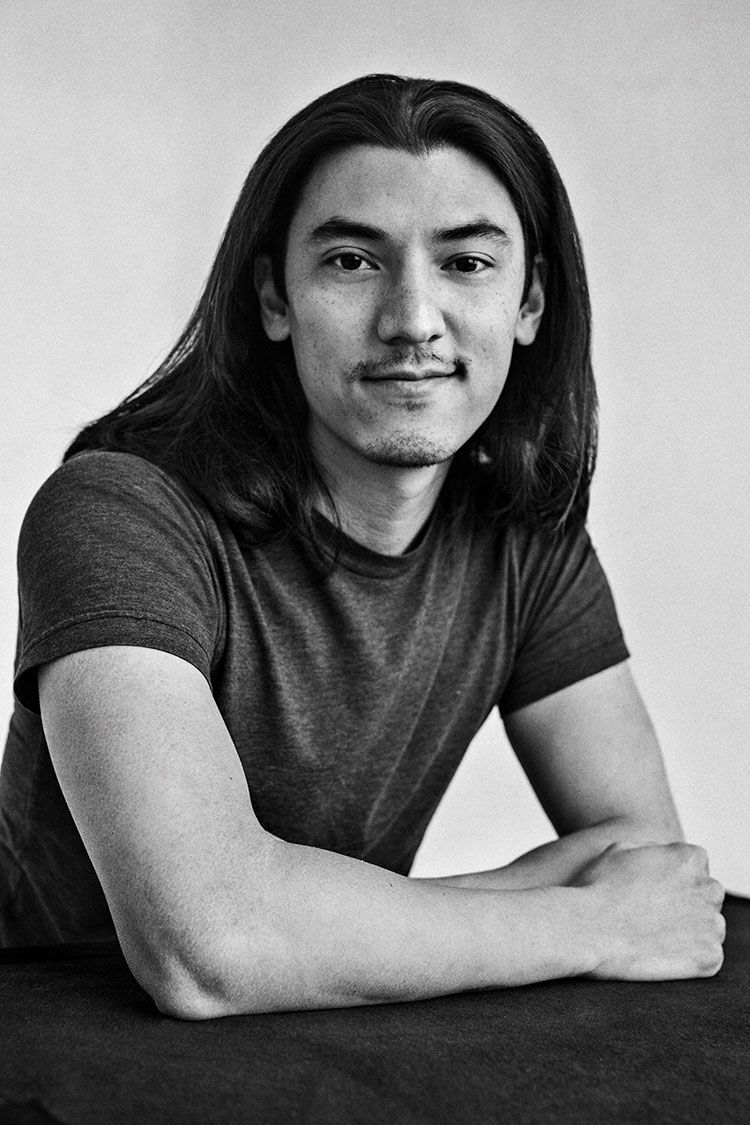

Among the recommendations of Netflix's algorithm these days is The Social Dilemma, a documentary presented last year at the Sundance Festival about the fallout that the massive social network presence has had on contemporary society. Through interviews with former employees and managers of Facebook, Instagram, Google and other Silicon Valley companies (as well as a small dramatization about an American median family), director Jeff Orlowski guides the viewer on the dark side of social networks by touching on topics such as depression, addiction and social disintegration caused by social network usage.

There's a degree of irony in the fact that it's an algorithm that suggests a movie that denounces how other algorithms are hurting our society. In addition, it will be the same algorithms represented by Orlowski as men inside the smartphone that will ensure that this article is read by users carefully profiled by the same algorithms. But in short, we'll make a reason for it, it's a complicated world. Orlowski's documentary is one of the most interesting content in Netflix's catalog but falls into many of the recurring mistakes when it comes to Silicon Valley, capitalism and social networks.

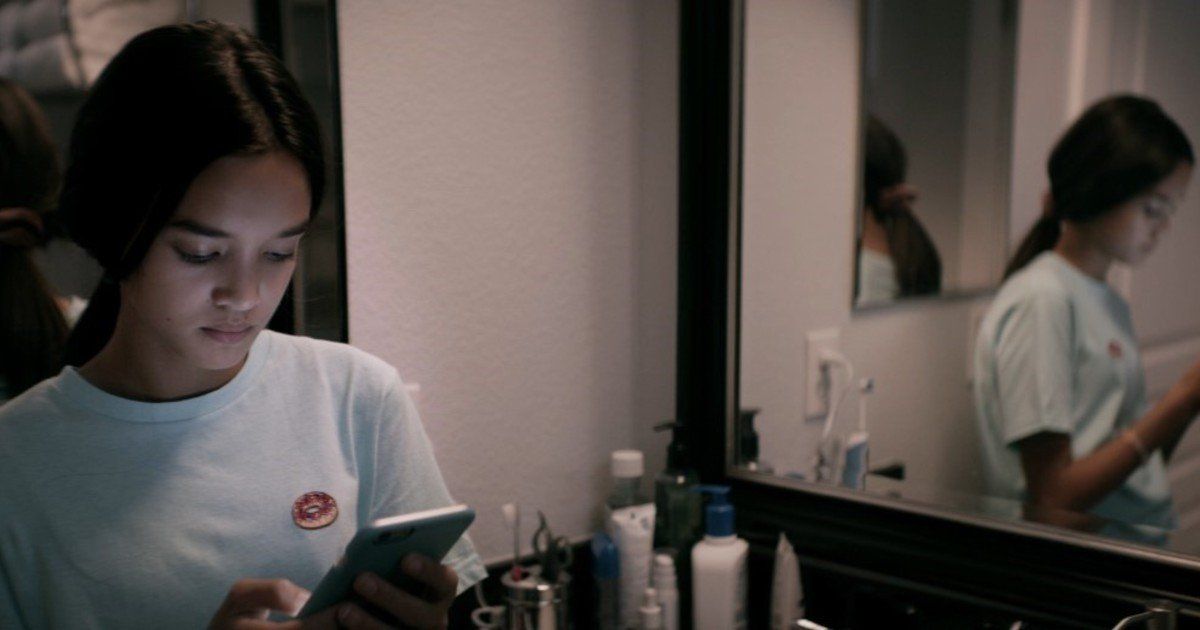

The Social Dilemma has the courage to immerse itself in a boundless and complicated topic to point the finger at the richest companies in the history of humanity - big tech precisely - denouncing how the algorithms and interfaces of social media are specially designed to steal our attention, manipulate the perception of the public's reality and, ultimately, mess up the democratic system. The documentary focuses on two aspects: the effects of social media at the individual level (depression, social anxiety and the substitution of reality) and at the collective level (fake news, political polarization, conspiracies and hate speech). The two examples of fiction in the documentary are Ben, a teenager who tries to disconnect for a week by failing and then falls into a rabbit hole of political polarization, and Isla, an 11-year-old who cries in front of the mirror because he sees his face without social filters.

Features such as infinite scrolling and refreshing of content common to all social networks - from TikTok to Instagram, via LinkedIn and Pinterest - are mechanisms borrowed from gambling whose sole goal is to monopolize a user's attention, and then slowly monetize by selling the data to the highest bidder. The concept can be summarized in the famous maxim: "If you are not paying for the product, then you are the product". But Orlowski points out that reprogramming user behavior is the only real goal of algorithms that handle push notifications, feeds, and engagement. Addiction is not a user weakness or a side effect - despite Justin Rosenstein, who among other things was the creator of Facebook's like, claiming that the goal was "spreading positivity around the world" - but the ultimate goal of the whole operation. Similarly, algorithms have realized that fake news and more extreme content are dramatically better performing than other content, with the effect of facilitating processes such as the election of Trump, Brexit or other social events that the film blames on social networks.

But there's another path.

— Justin Rosenstein (@rosenstein) September 9, 2020

Broken tech is a symptom (and accelerant) of a broken society. We have to fix it at the operating system level: putting *the people* in control of Big Tech. (Then, slowly, of our entire political economy.)

If these are the merits of the documentary, there is a downside - the metaphor or Orlowski himself used to explain the dark side of social networks - that is quite cumbersome: a deterministic view of technology. It would be to say: Orlowski and the respondents analyze social platforms, features and even the relationship with hardware in a completely decontextualized way, as if that same product were not the child of a socio-economic context and above all without thinking that every human being and society relates in a standardized way to technology. To put it another way, most of the evils come from technology, which, as Silicon Valley engineers, the world's highest-paid employees, suggests, would also be the solution to those same problems.

Taking up the two levels of analysis of the documentary, many psychology scholars specializing in digital Persuasion Theory use the drive-motivation scheme to understand how the attention of each individual user is hooked by the platforms. Everyone has different needs and motivations in the use of technology while the documentary analyzes only the profiling and operation of a platform, assuming that "likes" for example are the user's only motivation. Similarly, taking so many selfies does not necessarily lead to depression or social anxiety because the person who snaps is a person with a complex history, before being a user.

Similarly, The Social Dilemma glosses over one of the most interesting topics of human relationship with technology: the compression of space/time. Digital communication has rewritten the physical rules that used to govern our society (news cycles or trivially waiting for a letter) the portable devices made us available 24/7. Digital space and time have thus become an additional dimension to the real one, which each person has the task - very difficult - to balance with the size of the real. This kind of condition is not only the result of a business strategy, but is one of the changes of society over which no one really has control, which clearly has an anthropological impact far deeper than any button on a social network.

But the point on which the documentary loses some of the credibility built in the previous hour is the relationship between social networks and democracy. Orlowski bluntly states that democracies in crisis - from the US to Myanmar via the UK, Italy, Spain, Germany (Germany?) - all have one thing in common: social networks. To explain the crisis, very fashionable terms are used in the American debate, such as "polaraziation" or "filter bubbles" and "echo chambers" to describe the sneaky system by which social networks lock certain users in an ideological cage forcing them to listen to opinions that reinforce their beliefs and gradually radicalize them, altering their perception of reality.

This is a superficial analysis since social networks have changed news streams and the political agenda, but the practical impacts on social systems have been completely different depending on the context. The link between the "democracy crisis" and the rise of social networks is a clumsy way to avoid having to enter into much more complex discussions: from the demolition of collective identities to the level of wages, automation of jobs and growing social inequality. For this reason it becomes dangerous to simplify the discourse on the relationship between democracy and Western social networks - let us remember that China has an internet in its own right growing exponentially - trivializing a much more multifaceted and twisted relationship. What history has shown so far is that social media is very useful tools for mobilizing large masses of people - Black Lives Matter is the latest example, but even the Arab springs were organized on Twitter - but that fail miserably in structuring and managing power, another point that the documentary doesn't touch.

The Social Dilemma has the great merit of organizing and presenting themes that often bounce in the public conversation in a disorderly way and but more than a question presents the failure of a promise made by technology to humanity. But in the trap of pointing the finger at the Silicon Valley giants, you've destroyed the creative and inclusive internet of zeros to make it fat, but at the same time can't imagine a future outside the box created by the same companies and governments that control the digital space, eventually asking the perpetrators for a conviction and a solution to their own crimes.