The history and the aesthetics of Hysteric Glamour

The origins and the cultural influence of the Japanese brand that collaborated with Supreme

March 18th, 2021

Today, Supreme will present its new collection co-signed with Hysteric Glamour. The collection released today is actually the second that the two brands create together – with the first being released in September 2017 for the winter season of that year. But, just as happened with the collection created together with Yohji Yamamoto, this new collaborative capsule represents an opportunity to retrace the story of Hysteric Glamour, a brand famous in its field, sought after by collectors but also extremely niche and voluntarily detached from the dynamics of Western hype and marketing.

The importance of Hysteric Glamour is a historical issue: the brand was one of the main counter-cultural forces behind the Harajuku style, as well as one of the first brands, together with Hiroshi Fujiwara's Fragment, to develop a "rebellious" streetwear concept to express the feelings and aspirations of the new generations of Japanese, then paving the way for Undercover, BAPE and Number (N)ine that would all be born about a decade later. Founder Nobuhiko Kitamura's subversive work puts him on par with that of fashion history deities such as Vivienne Westwood, with the added merit of being one of the very first figures to "break the wall" between Japanese street culture and the Western society, bringing the charm of Harajuku's aesthetics around the world.

The genesis of a myth

The history of the brand is linked both to that of its founder, Nobuhiko Kitamura, as well as to the wider history of American culture in Japan – a melange of languages that lies at the basis of that cross-cultural dialogue that has generated so many of the Japanese fashion brands that we know today. During his teens, Kitamura had come into contact with Western counter-culture, the punk music of the Sex Pistols, Blondie, and the American new wave. One day he had gone out to buy imported records in Shinjuku, he came across a Tokyo Mode Gakuin Fashion School poster that he decided to sign up for. Graduated in 1984, he began working for Ozone Community, a cultural brand and hub that was one of the first interpreters of that particular historical-cultural moment in which the classic preppy style left room for a punk-based aesthetic through which the new generations loved to express themselves. It was within Ozone Community that Kitamura decided to launch his own brand first thinking only for women then making it mostly unisex, following his fascinations with the aesthetics of pop art and the 1960s mass media, for science fiction films, for punk music, for American comics, for fast cars and for porn.

This is how Kitamura told Empty Room magazine last February about the genesis of the brand:

I liked bands and rock, so I imagined Patti Smith 's hysterical stage presence and Blondie 's Deborah Harry 's glamorous feeling, so I thought that Hysteric Glamour would be okay, and I decided […] Just before I started doing Hysteric Glamour, I got a book about Dior's archive and a book called Art of Rock and read them both. When I first read Dior's book, I thought that Mrs. Kawakubo and Mr. Yohji were influenced by Dior and so on. So I thought everyone would be influenced by what they liked. That's why I liked Art of Rock and not Dior […] When I was a student, everyone used to wear their favorite brand's new pieces at school, but I didn't like wearing the same clothes as them. I thought it would be nice to go in a different direction, so I went around the second-hand clothing stores and searched for a vintage items and wore them. I think it's more interesting to pursue that kind of thing, whether it's your favorite culture or an item.

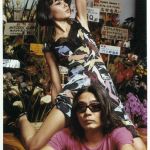

The success was immediate: thanks to Olive magazine, at the time a point of reference for the nascent Harajuku style, the taste for subversive graphics and that mix of aesthetics between Andy Warhol and Kitamura's punk came to young people from all over Japan, who fell in love with it.

The reasons behind the success

The aesthetics cultivated by Kitamura are at the crossroads of multiple influences: its foundations are, as mentioned, the aesthetics of the advertisements of the late 1960s and early 1970s and the reworkings of it made by Andy Warhol; this initial blend was then joined by the visual languages of the posters of the time and the many references to punk and new wave that emerged from Greenwhich Village along with psychedelia and comics but also the intuition to rebuild and work on vintage garments and military surpluses that went for the most part at the time among the young people of Tokyo. More than in his influences, however, the success of Kitamura and Hysteric Glamour is due to his direct grip on the zeitgeist of the time, the chaotic and rough beauty infused into his creations by his artisan approach. In an interview with Nylon, Kitamura said:

When I was just starting out, there was no one doing what I was doing. I had no experience and no teachers, so I just read books.

This consideration contains a little of the whole history of those first streetwear brands born in those years: the same as Ozone Community was managed and directed by young creatives who worked according to artisanal and often deliberately anti-commercial logics. If the first generation of great Japanese designers (Rai Kawakubo, Yohji Yamamoto and Issey Miyake) had moved very soon to a higher type of fashion, often located in Paris and organized in traditional collections, and therefore necessarily distant from the street sensibilities, the so-called Mansion Makers (the nickname given to those designers who, like Kitamura, often produced their own collections at home, in arranged ateliers) produced cheaper clothes that better interpreted that push of opposition to the mainstream that animated the younger generations of the time – expressed through the explosion of popularity of bōsōzoku bikers and their uniform, known as tokkō-fuku (in Japanese 攻服) which means "special attack uniform".

Kitamura's decision to turn his back on commercial and conservative fashion to devote himself exclusively to the world of his cultural references, tastes and inspirations proved successful as he not only showed that an alternative path could exist but also because the rebellious spirit and "raw" aesthetics of his creations were able to enrich and expand more and more the culture they themselves created, finding an increasing number of like-minded spirits outside of original Japan and building a cultural multiverse that begins with clothes, continued in the references and quotes contained in them, and ended up involving art, publications, and great creative figures who marked their era — always in open opposition to the mainstream.

From Japan to the world

By the late 1980s, the brand had opened a temporary store in New York, attracting the attention of bands and creatives such as Sonic Youth, Iggy Pop, Terry Richardson and Keith Haring – but the store lasted just two years. The first official collaboration of the brand was with the band Sonic Youth, so Kitamura designed t-shirts that even Kurt Cobain wore in the family photos of his wife Courtney Love, a great friend of the brand. The turning point came in 1991. It was then that Hysteric Glamour opened its first store in London launching into the international market and its clothes ended up on the idols of Kitamura himself – personalities such as Marc Lebon and the Sex Pistols. In the following years, the founder's ambitions expanded towards actual art. In 1993, a series of photobooks were created with figures such as Daido Moriyama, Nobuyoshi Araki, Terry Richardson, Russ Meyers and Rita Ackerman as guest art directors. A collaborative activity that continued in various forms to culminate with the opening of the Rat Hole Gallery in Tokyo.

In the same year, Kitamura worked with the Andy Warhol Foundation closing the circle of his inspirations with a limited edition collection that united Kitamura's artworks with those of the father of pop-art. In 2013 another collaboration with Playboy returned to explore the references to vintage erotic art that the brand had been carrying since its inception and finally the collaboration with Supreme in 2017 finally made the brand dialogue with the wave of Western streetwear and the new generations. Today, the brand is spread to all major fashion capitals outside Japan – but ironically not in the US, which is the main source of Kitamura's inspirations. Kitamura's most beautiful and unexpected moment will, however, remain his lightning-fast appearance in Sofia Coppola's cult movie Lost in Translation which was inspired by some parties he had attended with Kitamura in Tokyo to compose his ode to the capital of Japan.

Given Kitamura's appreciation for collaborations (many were those with Mastermind or Undercover), his ability to maintain the cult status of his brand and his complete rejection of the mainstream, as well as the fame of the first collaboration, it is clear why it was decided to renew it with a second chapter that, hopefully, will manage to bring the heritage of the Kitamura brand towards an even more distant future. The same designer, in the interview with Empty Room last February, said he was optimistic about the future:

I think that the way of thinking about clothes has changed completely from the past. […] Depending on how you show it and how you express it, even if it's very simple, if you add value, [one's creative work, ed] will spread normally. I think Instagram has a strong influence on that. It's interesting that independent brands and projects are suitable for the present era.

.webp)

.jpg)

.jpg)