Ghali's pink calls out Italian toxic masculinity The world of hip-hop moves on, its public seems stuck in the past

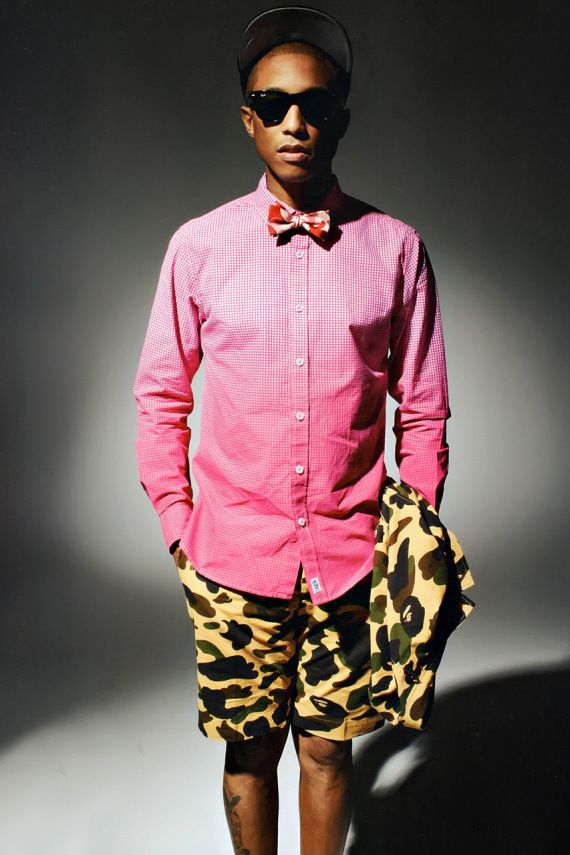

In an interview for the November issue of GQ, "The New Masculinity Issue", Pharrell Williams answered a question about the greater simplicity with which, following the line he had followed in previous years, artists such as Lil Uzi or Young Thug (or A$AP Rocky and Tyler the Creator themselves) have managed to carry on a more androgynous aesthetic and wear women's clothing:

«And my point is, why not? What rule [is there]? And when people start using religion as the reason someone shouldn't wear something, I'm like, What are you talking about? There was no such thing as a bra or blouse in any of the old sacred texts. What are you talking about?I was also born in a different era, where the rules of the matrix at that time allowed a lot of things that would never fly today».

In the same interview, Pharrell Williams repudiated some of his old lyrics for the way he objectified women and sexuality.

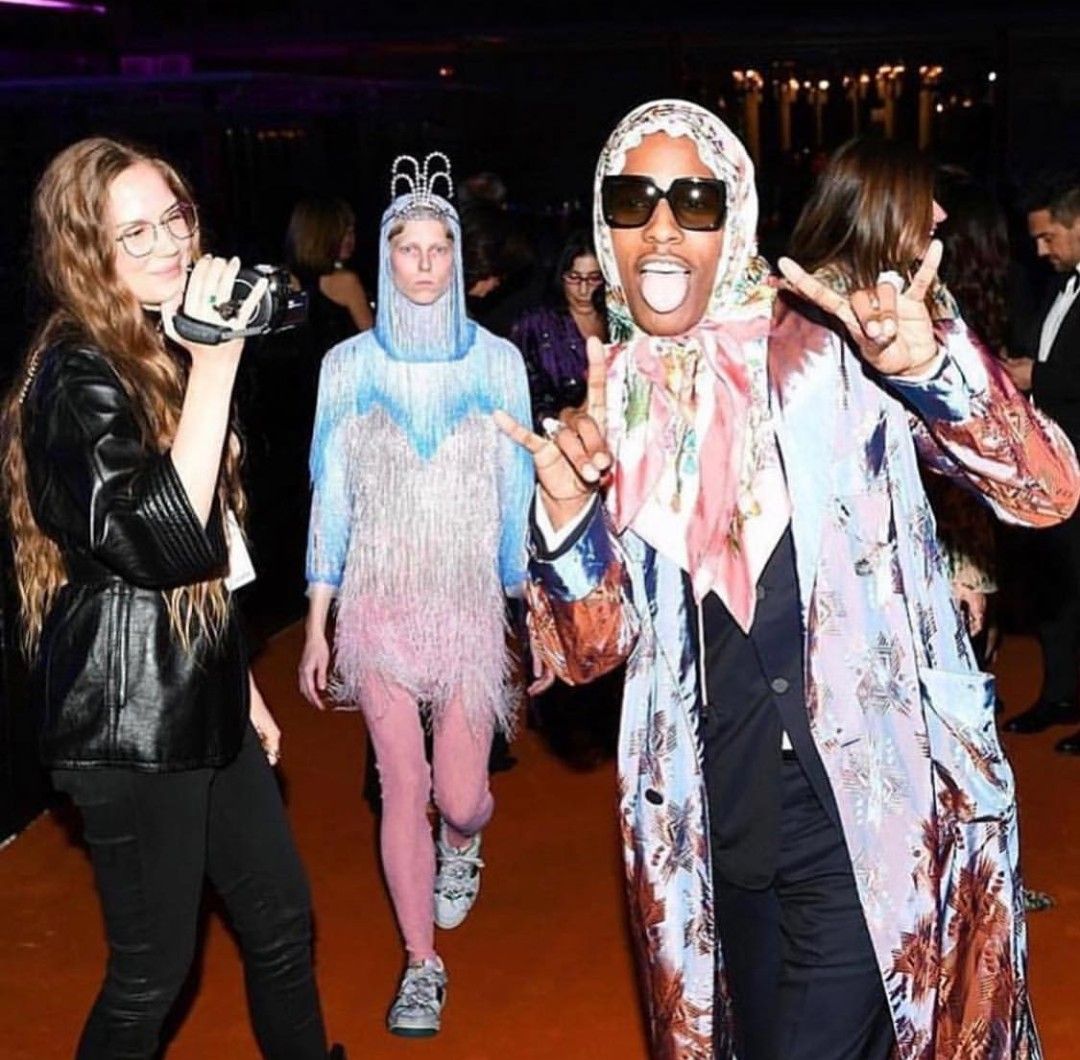

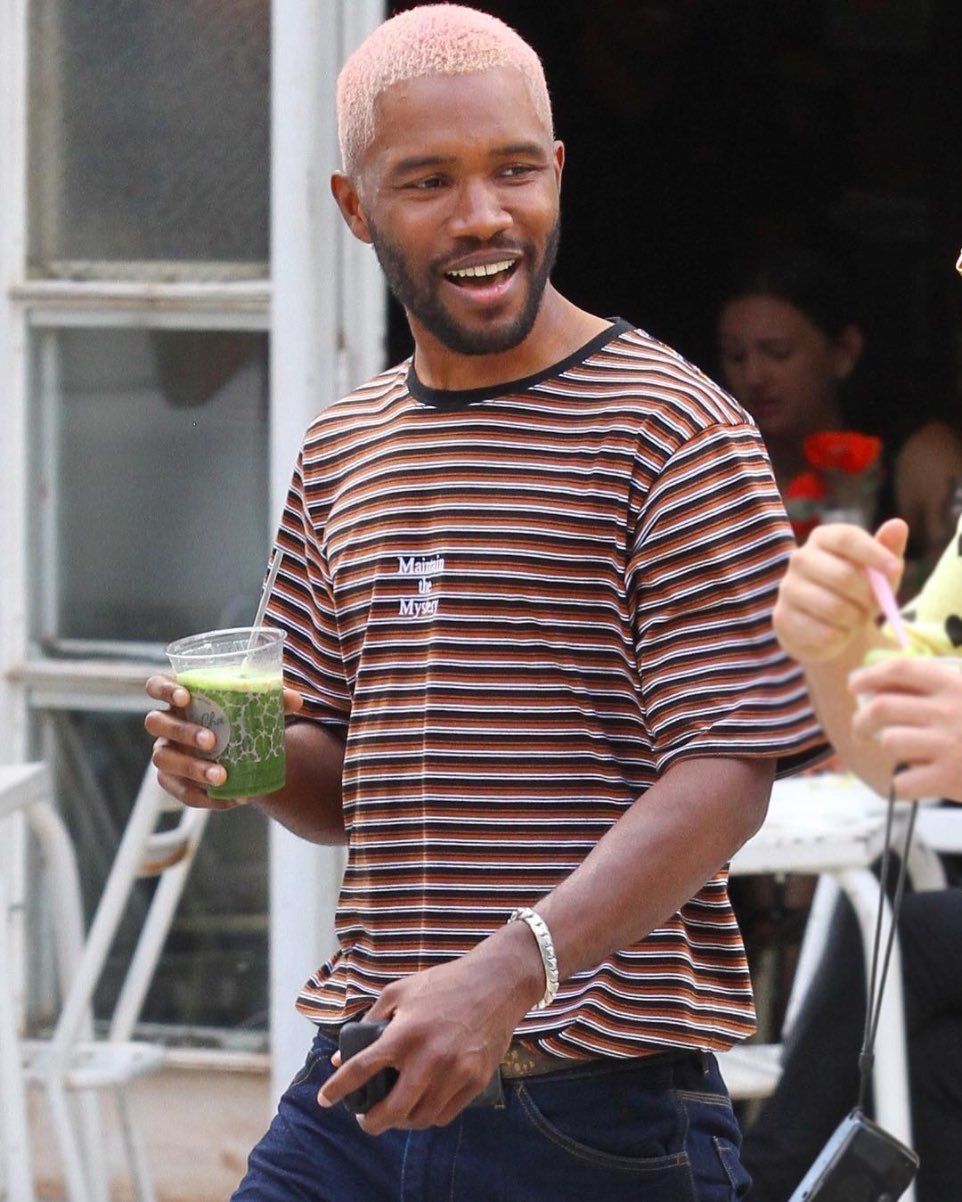

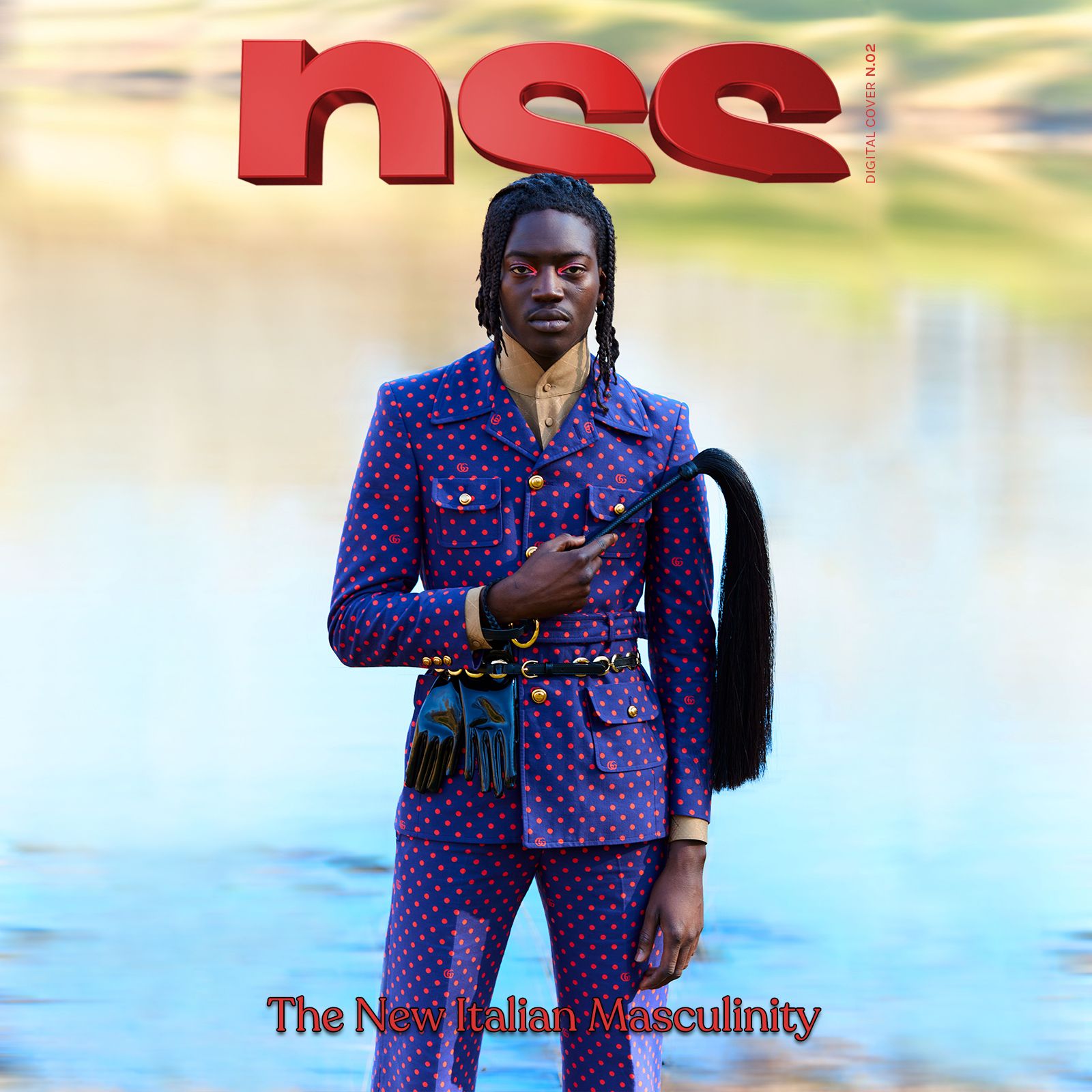

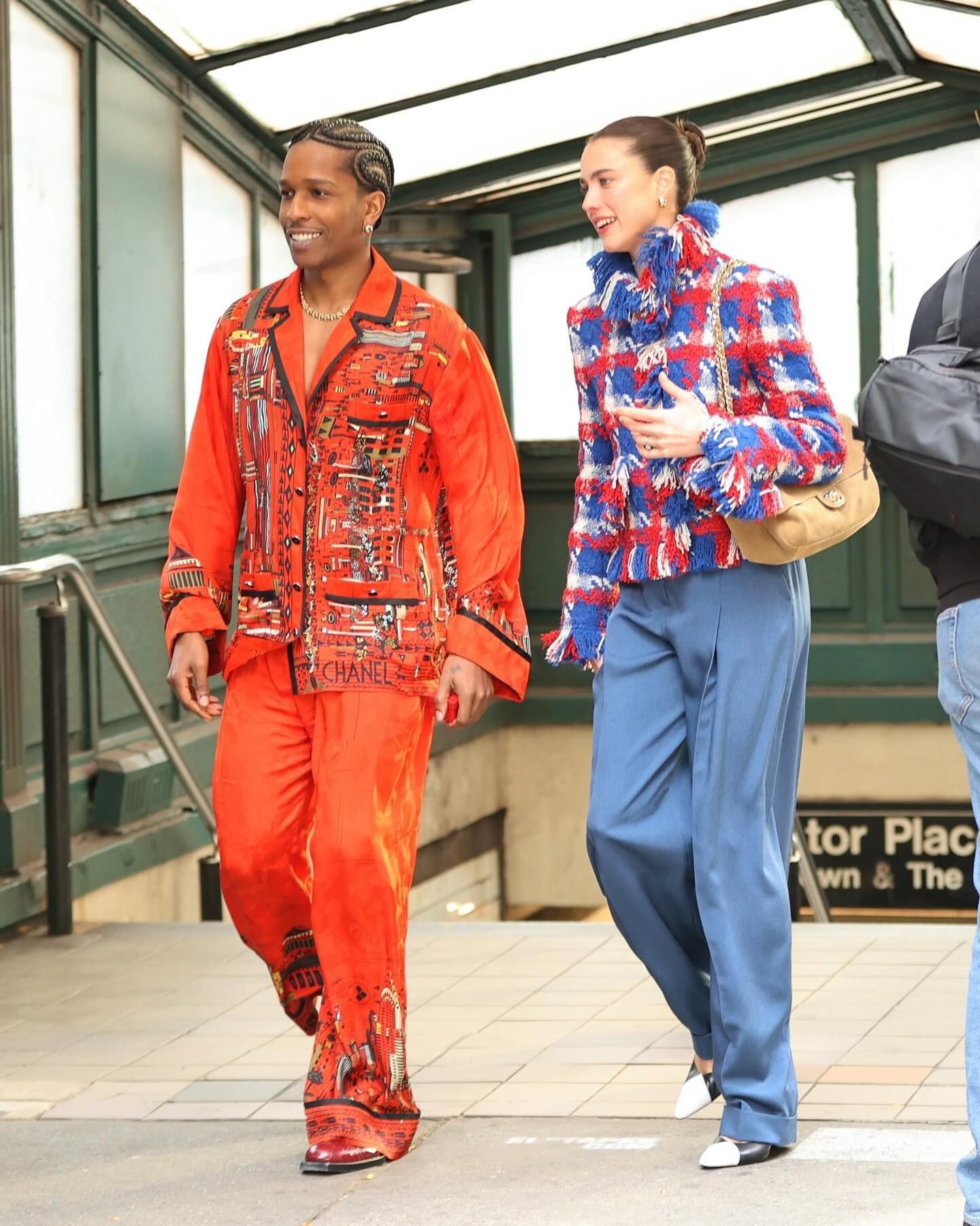

Rap (and urban music in general) has undergone an epochal change since the 1990s in the way they interacted with sexuality and its aesthetic representation. Rap's relationship with homosexuality and gender-fluid clothing was perhaps the main social evolution that the past decade has left us, as The Guardian wrote in 2012 ("From Frank Ocean coming out to Jay-Z backing gay marriage, hip-hop seemed to be shaking off its homophobic mindset this year") and as Vogue reiterated in July 2019 in a piece titled "This was the decade that hip-hop style got femme". The fashion industry - and the relationship between rappers and major industry brands - has been central to the process of rewriting the canons of masculinity that rap, from mainstream gender as it has become, has been able to channel into society. The cover of Young Thug's "Jeffery" - in which the rapper wore a tailored suit made by Italian designer Alessandro Trincione - the Gucci babushka worn by A$AP Rocky, were some of the moments when fashion was able to serve as a vehicle for old dogmas and stereotypes about male sexuality.

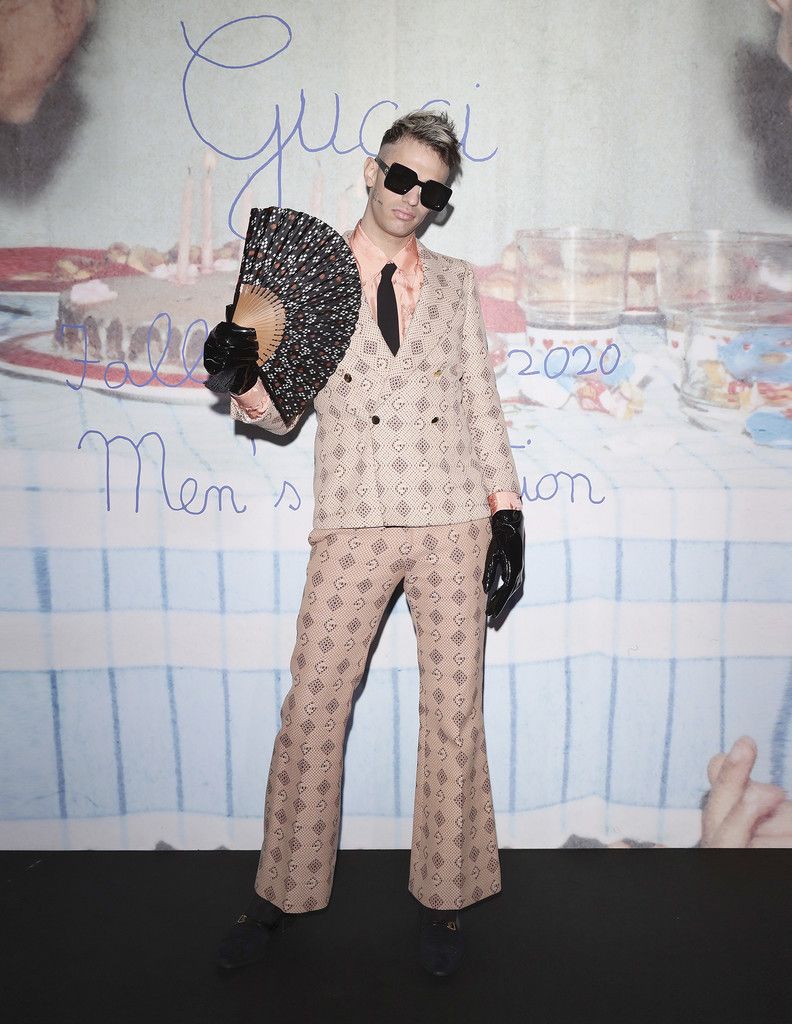

Not always and not everywhere, however, this process can be said at an advanced stage, let alone complete. Italy for example - although Alessandro Michele has actively contributed to the redefinition of masculine aesthetics - still struggles to accept a certain fluidity of aesthetic gender, especially in relation to what is conceived as the most "masculine" of the arts: rap. A few days after her participation in Gucci's MFW show, Ghali posted a photo of his outfit on her Instagram Stories: a pink coat with heeled boots, all, of course, Gucci. The answers in DM must have had the level of homophobic regurgitation, so much so that Ghali replied in subsequent stories:

«Guys, you're the worst with your comments, you don't have any sensibility. Sometimes I'm ashamed of having people like that among my followers, when you say things like that. And you call me gay, and things like that... Sorry but where would be the problem? Even if it were, what would be the problem? Also, do you think that I should listen to you?», and concluded: «We had different lives, we had different influences and we're not the same. So stop with those comments».

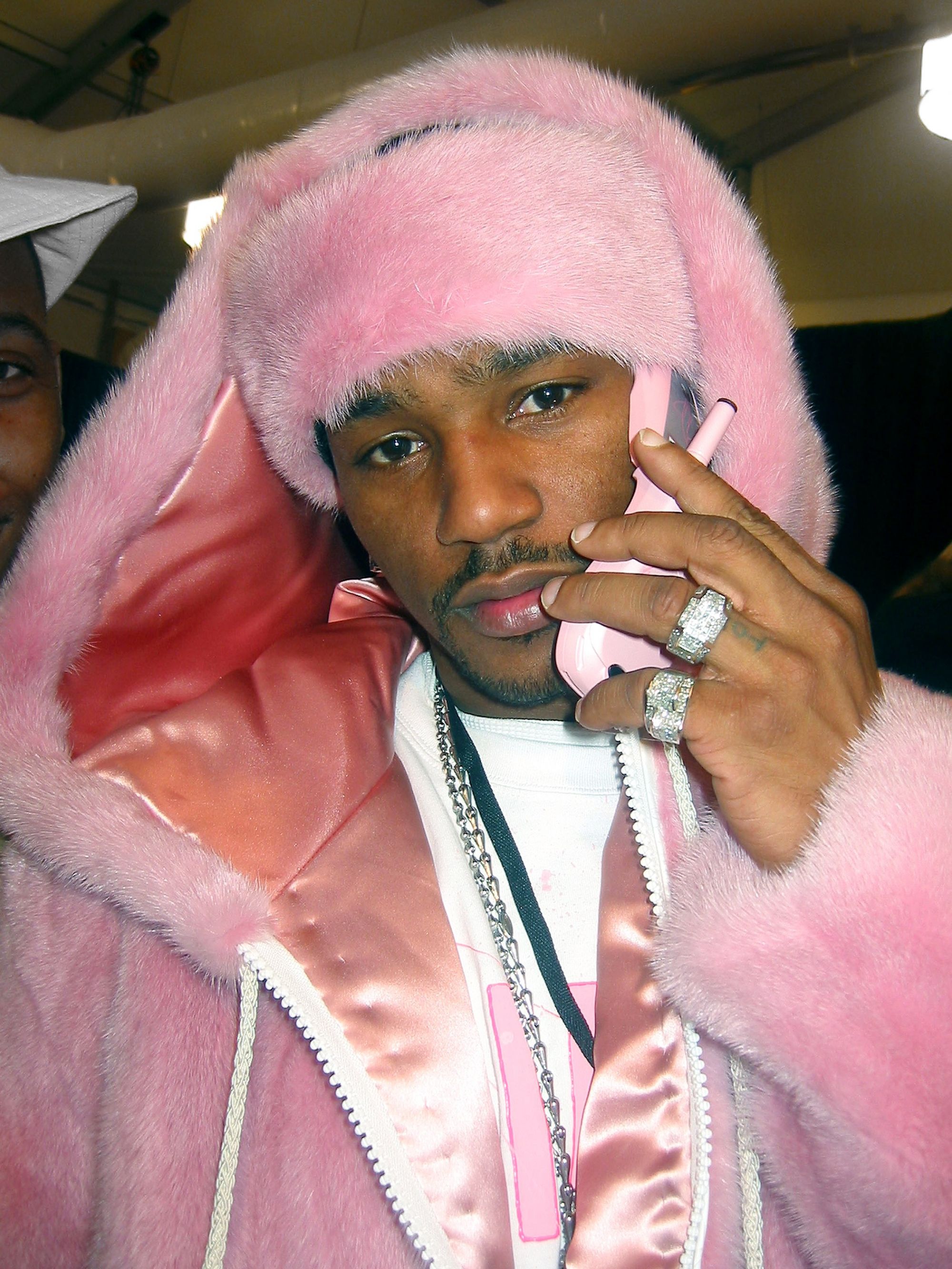

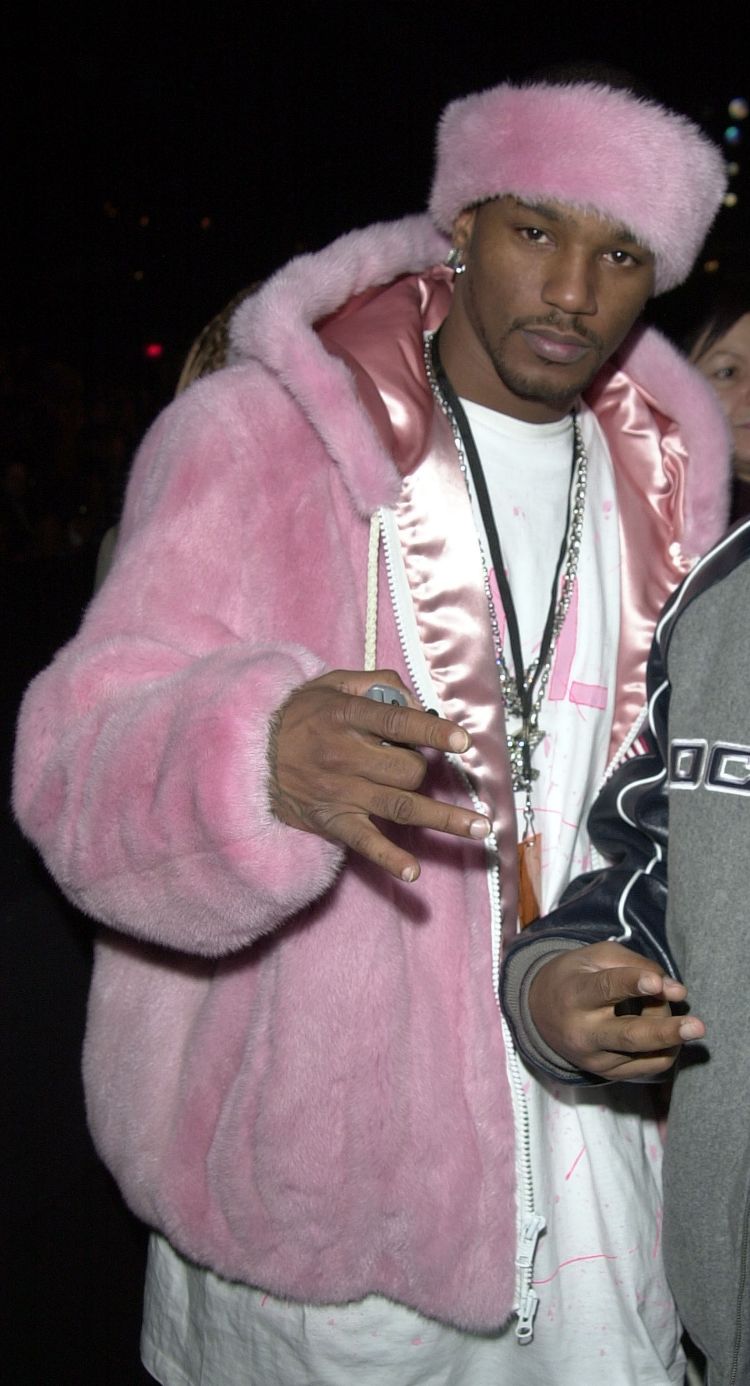

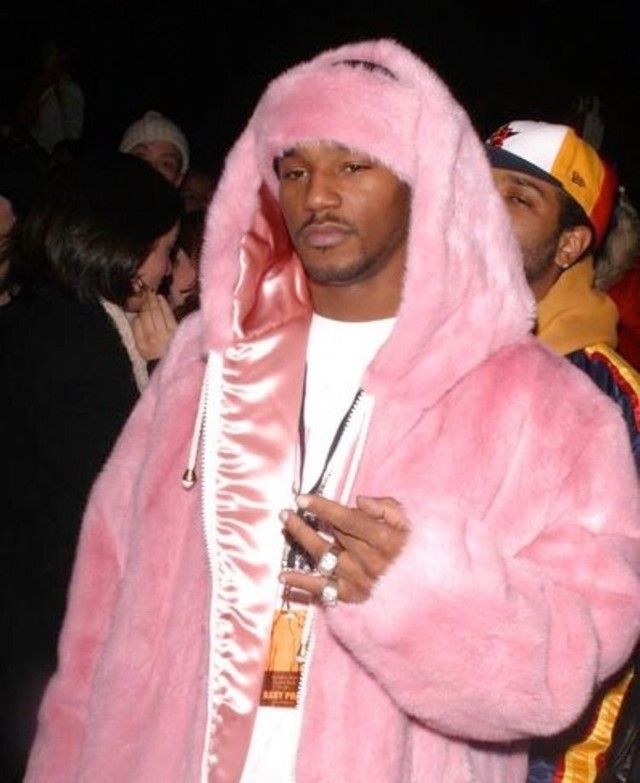

Ghali's call-out is important, almost fundamental, in a culture - that of the new Italian rap - that has evolved too quickly and in a perhaps unharmonious way, finding itself coming to terms with the international opening that its brightest stars (Ghali and Sfera Ebbasta on all) have managed to get, and on the other with an audience too young and provincial to be able to keep up. The almost androgynous aesthetic that Ghali is sporting recently - since his first appearances in Gucci and Dior - is practically unique in the Italian music scene (with the recent exception, perhaps, of Achille Lauro) and also distant from the pink furs of Sfera Ebbasta or the Dark Polo Gang. Those furs are in some ways similar to those worn by Cam'ron of Dipset in 2002, in a photo that has become iconic for the world of rap and its relationship with fashion:

«Cam’ron, best known for his knack for elastic bars, punchy humour and excessive machismo, kicked off a trend – and a remarkable one at that in the hyper-masculine world of early 2000s hip hop.», Calum Gordon wrote on Dazed.

However, it's certainly not pink that makes a man's clothing androgynous, as are women's glasses or heeled boots. What the '10s of 2000 brought in dowry to rap (and fashionable) is a general propensity for an expression of one's aesthetic identity as free as possible. And that's where we can incorporate Ghali's recent aesthetic. All the brands, from Gucci to Louis Vuitton in Telfar, have managed to adapt, opening up new possibilities also for the fashion and communication industries, which have allowed Pharrel Williams, for example, to become the first man to lead a campaign of Chanel bags.

The importance of this process of increasing freedom of expression of one's aesthetics - which is not necessarily linked to the expression of one's sexuality - lies in ensuring that a part of the public that historically had never found representation the opportunity to express themselves, and to do so by identifying with artists who can simultaneously perform as headliners at Coachella, organize queer parties in New York and be protagonists of Prada's new menswear campaign. And it's essential that Italy - where many of the protagonists of this process reside - becomes an active part of this trend: at a time when civil society is struggling to stand as a role model, fashion, art and music can play a role important in the education of the public.