Is it possible to do a concert in a war zone? From Springsteen in Berlin to Neil Young's concert in Ukraine

Following the clash between Trump and Zelensky, Canadian rocker Neil Young has announced his intention to hold a concert in Ukraine. Not just an offhand remark, but an official announcement, reported by various news outlets with a dedicated full-page article on the artist’s website. However, at the moment, nothing is confirmed: «We are in the middle of negotiations and will announce the details here. Keep on rockin’ in the free world,» reads the statement. So far, the Canadian singer’s intention is to hold a free concert in Ukraine as the opening event of his European mini-tour, which will take him through Northern Europe from June 18 to July 6 this summer. It is difficult to say whether the concert in Ukraine will actually take place: many, following the announcement, have questioned how feasible the endeavor really is, considering that Ukraine remains an active war zone. However, this wouldn’t be the first time: in the past, there have been rare cases of artists performing in war zones. Below, we have compiled a list of the most memorable instances to date.

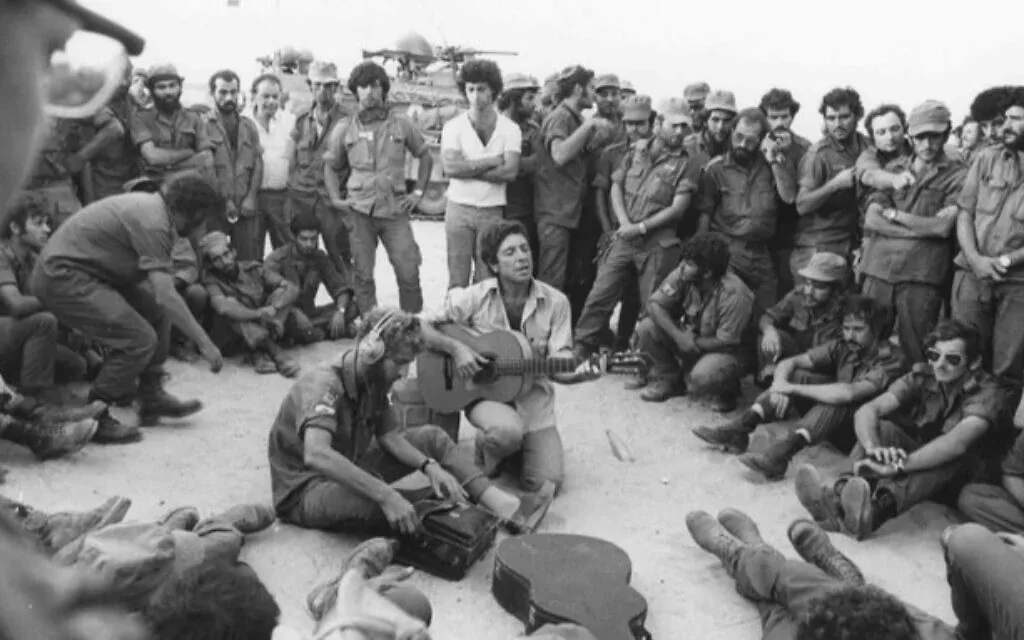

Leonard Cohen’s Fire Song in the Sinai (1973)

New York Times journalist Matti Friedman recounts in the book Il canto del fuoco the incredible story of the tour that Leonard Cohen undertook in the Sinai in 1973 during the Yom Kippur War, which saw Egyptian and Syrian forces facing off against the state of Israel. It was not, in reality, a planned tour: Cohen had traveled to Tel Aviv without a clear reason in mind and, most notably, without even bringing a guitar. One afternoon, however, he was recognized by some local musicians who asked if he wanted to join them in playing for Israeli troops engaged in the war. Thus began a musical and spiritual journey that was neither simple nor free of contradictions: the Canadian singer-songwriter came into close contact with military life, and the soldiers connected with his songs. In the end, both sides benefited from the experience on a deeply human level.

Rory Gallagher’s Tour in Northern Ireland (1974)

Unlike Cohen’s spontaneous decision, Rory Gallagher’s tour in Northern Ireland in 1974 was a much more deliberate choice: a fully organized tour in the midst of the so-called Troubles—the armed conflict between Northern Irish nationalists and unionists that plagued the country for over thirty years, both within and beyond its borders. A remarkable concert film by Tony Palmer documents the tour’s main highlights, one of the most memorable being the New Year’s Eve concert in Belfast. At the time, the city was living in terror, with deserted streets and people preferring to stay indoors. Just the night before, Belfast had been devastated by the explosion of ten bombs placed in key locations, including a children’s cinema. Undeterred, Rory Gallagher declared, «I see no reason not to play in Belfast. There are still kids living here.» Gallagher had grown up in Cork, in southern Ireland, while his bandmates, Wilgar Campbell and Gerry McAvoy, were natives of Belfast. All three knew how much the city’s youth, torn apart by violence, needed music. On the Irish guitarist’s website, a rare testimony from the time captures the enthusiasm of the audience present that day at Ulster Hall. «Are we giving too much importance to rock?« asks the author at one point. «No,» replies Jim Aikin, the event’s organizer. «It does something that nothing else can. If we can still hold a concert, it can only be a good thing.»

The Concerts of the Cold War: From the Berlin Wall to the Soviet Union (1987-1988)

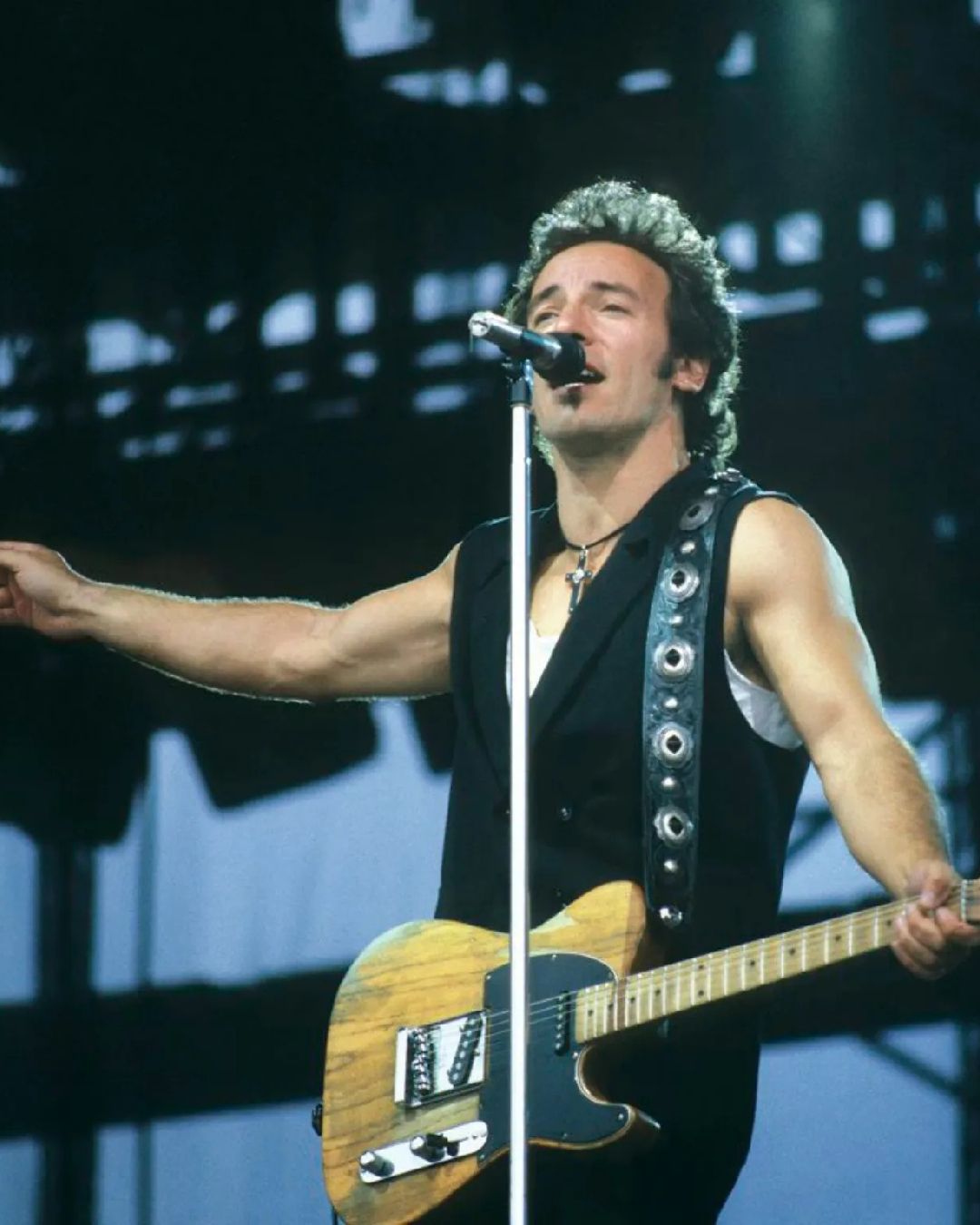

They may not be considered true performances in war zones, but some concerts held near the Berlin Wall before its fall in 1989 still deserve a special mention. The concert in West Berlin by David Bowie in 1987, complete with a greeting «to all the friends on the other side of the wall» who gathered to participate in the event despite the military barrier. Later, with the support of the Fdj - the Communist Youth Federation, two other crucial concerts were held in East Berlin: Bob Dylan’s concert on September 17, 1987, in front of an astonished crowd of nearly one hundred thousand people; and even more so, the Bruce Springsteen concert on July 19, 1988, this time in front of about 300,000 people, to whom the Boss said a few simple but deeply emotional words: «I didn't come here to play for or against any government, but only to play rock'n'roll for you, in the hope that one day all barriers will be torn down.» When he then performed Chimes of Freedom by Bob Dylan, it became clear to everyone that sometimes a song can mean more than a thousand political speeches. On the other side of the Iron Curtain, one of the first to perform a concert was Billy Joel, in the summer of 1987: over six dates (three in Moscow and three in Leningrad), he managed to bring together two distant worlds, easing the tensions of an audience initially surprised by such energy and partially immobile, as if frozen by years of the Cold War and isolation. Joel even smashed his piano on the floor and ended up stage diving, lifted by a delirious crowd - widely documented in the documentary Billy Joel - A Matter of Trust: The Bridge to Russia.

Concerts in Sarajevo during the war in former Yugoslavia (1992-1997)

In the history of the war in former Yugoslavia, the siege of Sarajevo holds a particularly tragic place, as it was the longest siege in modern warfare history since World War II: an entire city held hostage by bombings and snipers for 1,425 days, from April 5, 1992, to February 29, 1996. There are various musical testimonies proving that in Sarajevo, music was an enemy of war from the very beginning. In May 1992, a mortar shell killed twenty-two people in a market. The cellist Vedran Smailović went to the site and played Albinoni’s Adagio in G minor for twenty-two consecutive days. Throughout the siege, Smailović continued performing across the city, ignoring the danger, even playing among the ruins of the National Library, consumed by flames—an event to which the C.S.I. dedicated the song Cupe vampe. Despite the deaths of many musicians, even the city's Symphony Orchestra never stopped playing during the siege. Many other young local musicians followed this example: to survive not only physically but also spiritually, they began organizing underground theater performances and concerts, often held in basements and underground venues, using emergency power generators.

During those years, besides performances by local bands, there were also two outstanding international concerts: the concert by Bruce Dickinson (legendary singer of Iron Maiden) in 1994 and the concert by U2 in 1997. There is a big difference between the two events. Bruce Dickinson’s concert, together with Skunkworks—his solo tour band—was held in a small club while the war was still ongoing, meaning there was a risk of stepping on a grenade or being hit by a bullet. U2’s concert, on the other hand, took place in a large stadium after the signing of the Dayton Peace Accords (1995), in a much safer situation. The invitation to play in Sarajevo had actually come years earlier: U2 had been courted since 1993 when writer-activist and filmmaker Bill Carter—who had moved to Sarajevo—saw an MTV commercial in which Bono Vox expressed solidarity with the Bosnian people. Carter had the crazy idea of trying to contact him, and incredibly, he managed to secure a historic interview where he extended the invitation. Since bringing such a huge band to play in Sarajevo during the war was practically impossible, they decided to set up video connections during the band’s world tour. These “broadcasts” were later interrupted when it started feeling like the initiative was becoming more of an advertisement for U2 rather than a moment of reflection on the war. However, the band’s promise to play in Sarajevo as soon as possible was kept, culminating in a major concert four years later, captured in the 2023 documentary Kiss The Future.

To hold a concert in Sarajevo during the war, however, required a certain level of recklessness. That recklessness came from Bruce Dickinson. The original plan seemed relatively safe: he and his band would fly to Split and then reach Sarajevo by helicopter, escorted by UN peacekeepers. They would perform and leave the same way they arrived. However, once in Croatia, they were told the situation had worsened and that it was too dangerous to fly into Sarajevo—they were advised to return to England. Dickinson thought for a moment and then said, «Okay, never mind, no helicopter; I don’t know how, but we’ll find another way to get there.» And indeed, they found a way through The Serious Road Trip, an NGO that brings entertainment and hope to war zones. They traveled in one of the organization’s vans, hearing gunfire in the night, and ultimately played the concert—something the residents still remember with tears, as captured in another moving documentary, Scream For Me Sarajevo.

«You have to make people feel something, give them something better. But it involves risk, and if you’ve lived your whole life without taking risks, I don’t know what you can do. Maybe you should just kill yourself to avoid risk altogether—the only way to avoid risk is to be dead. You can’t live your whole life like that; that’s not life.»