Is minimalism suffocating architecture? How the “New Urbanism” movement intends to revive our cities

Among the many orders and memoranda signed by Donald Trump in the first weeks of his presidency, there was one called "Promoting Beautiful Federal Civic Architecture," stating that «federal public buildings should be visibly identifiable as civic buildings and respect regional, traditional, and classical architectural heritage, in order to elevate and beautify public spaces and ennoble the United States and our system of self-government». The memorandum reignited a debate on the meaning, history, and political undertones of architecture in cities across the Western world, which has recently become a perhaps secondary but no less pervasive aspect of the broader culture wars dividing the Western public, mostly online, as they compare the romantic beauty of past urban buildings and decorations with the sterile functionalism of today’s architecture: where are the columns, the bas-reliefs, the decorations, and the details that made the cities of the past so evocative? On X and YouTube, stories circulate about places like the Parisian suburb of Le Plessis-Robinson, an anonymous stretch of concrete buildings transformed over three decades into a romantic village and now a symbol of a movement known as New Urbanism—a movement born to counteract the bleakness and anonymity of modern cities. Under this and other names, the movement is strong on social platforms like X and Facebook, and it would be easy to adhere to it if many of its ideas were not tied to highly reactionary and conservative political views—even though the movement's popularity and social purpose make it acceptable on an aesthetic and philosophical level. However, the mere existence of such a movement raises the question: is minimalism destroying our cities?

In metropolises around the world, urban architecture and furnishings seem to look the same: sleek benches, anonymous streetlights, squared-off bollards, glass-and-steel skyscrapers, and interiors characterized by clean design, using wood and pastel shades. Milan’s skyline resembles Tokyo’s or New York’s. The lack of identity in cities and spaces was theorized by Marc Augé in his book Non-Places. In 1992, the French anthropologist introduced the concept of "non-place" to describe those built spaces defined by their transience and anonymity. Places like airports, gas stations, and hotels tend to exhibit a utilitarian sterility, prioritizing function and efficiency over human expression. Even Rem Koolhaas, in 1995, emphasized the homogenization of the contemporary city. In his essay The Generic City, the Dutch architect and scholar claimed that the contemporary city is like an airport—identical everywhere. «Is it possible to theorize this convergence? And if so, what ultimate configuration does it aspire to? Convergence is possible only at the cost of losing identity» (Rem Koolhaas, Junkspace, Quodlibet, 2006). Augé’s concept of "non-place" thus extends to the entire city. Koolhaas argues that the absence of soul is becoming the dominant trend in urban design, and in simplistic terms, minimalism is often blamed as the main cause.

@jupiterari What happened ? Why is modern architecture so ugly ? #architecture #france #paris #cadaques #collioure #sorbonne #architecturestudent #architect #travel #spain #historical #monument #fyp #foryou #fypツ #ugly original sound - kirsten_ssss

But what is minimalism really? A quick look at Wikipedia reveals countless definitions: there is political minimalism, artistic minimalism, musical minimalism, architectural minimalism, photographic minimalism, and advertising minimalism. Essentially, minimalism appears more as a philosophical approach to life rather than a well-defined artistic and cultural movement. The term was coined in 1965 by British art philosopher Richard Wollheim—in his article “Minimal Art,” he sought to describe the works of Donald Judd, Robert Morris, Carl Andre, Dan Flavin, and Sol LeWitt—before being retroactively applied to other artistic fields. Minimalist style, for example, can be seen in the concise prose of Ernest Hemingway and Raymond Carver, in the works of artists like Barnett Newman, Robert Rauschenberg, and Ad Reinhardt, and even in those of Piero Manzoni and Yves Klein, as well as in the music of Rhys Chatham and Philip Glass. The common thread connecting them is an essential approach to the object in space: eliminating excess, emphasizing functionality, and focusing on materials and forms are the core principles of minimalism. In architecture, from modernism to the present day—with exceptions such as Robert Venturi’s postmodernism—there has been a consistent evolution toward this philosophy, although the theoretical component has been sidelined in favor of practicality.

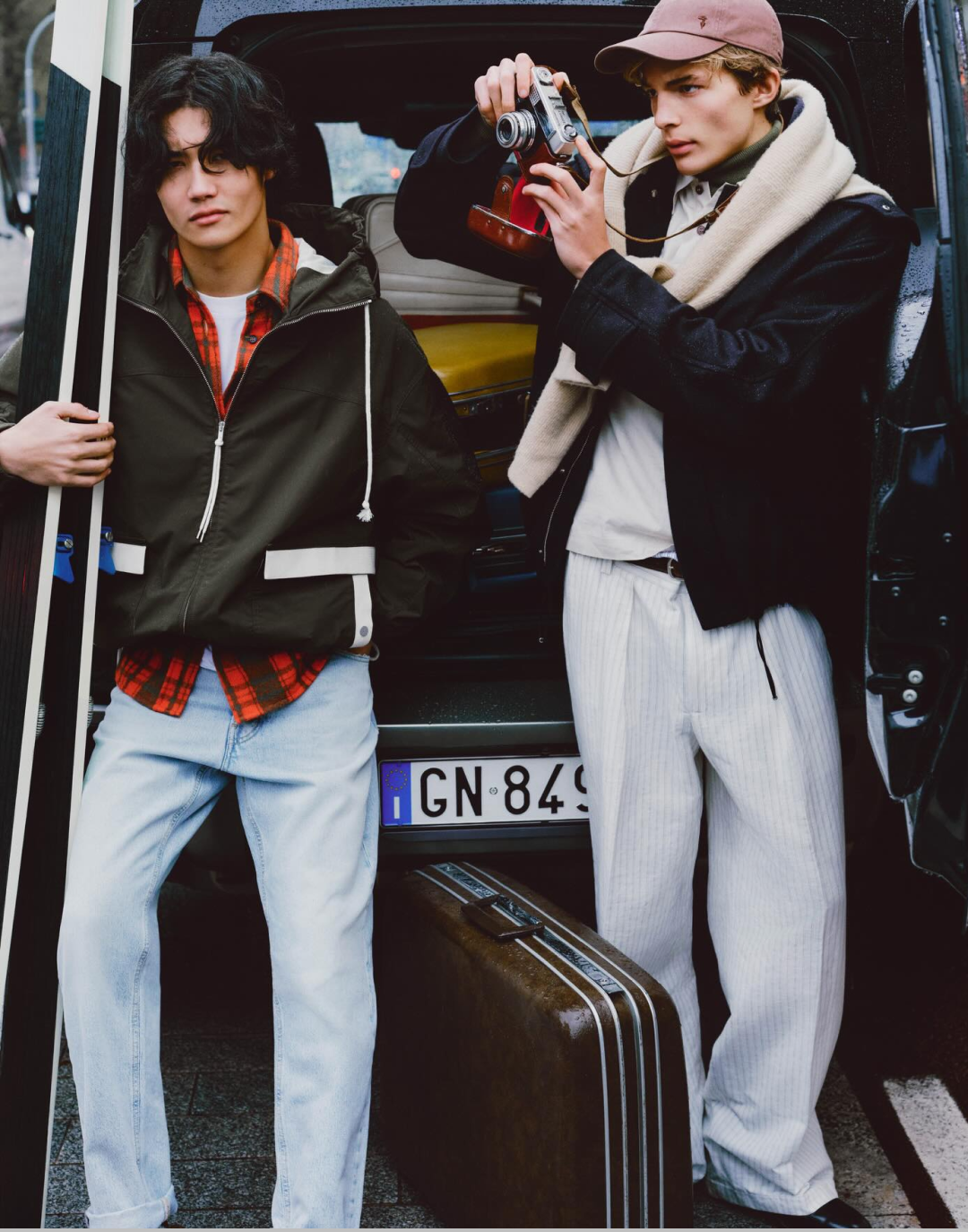

Ugliest Italian City (Milano)

— NeoTraditional Architecture Memes (@VicctorianChad) February 24, 2024

VS

Most Beautiful American City (Boston) pic.twitter.com/94JeMTCi4y

On one hand, there is the economic factor: the use of essential materials and industrialized processes makes it easier and sometimes more cost-effective to produce functional objects rather than adding ornaments and details, even if mass-produced. On the other hand, minimalist objects and architecture are associated with a timeless modernity that remains fresh over the years. However, many believe that minimalist design has impoverished architecture and design, leading to a standardization that has stripped objects, buildings, and urban spaces of personality. A recent post by Hut, an Instagram page dedicated to architecture, revived a trend that went viral on Twitter in 2021 titled The Danger of Minimalist Design, which blamed "unconscious minimalism" for the disappearance of details and colors, evoking nostalgia for the more varied and imaginative creations of the past. Is this just a case of golden age syndrome, where the present (and every innovation with it) seems inferior to an idealized past? One thing is certain: our home interiors all look alike (Scandinavian design echoing the Airbnb-inspired Airspace style), our cars are indistinguishable, as are restaurants and cafes. Perhaps we feel at home anywhere in the world precisely because we have already seen it all, avoiding the disorienting effect of the unfamiliar.

But the real danger does not lie solely in aesthetic repetition; rather, it is in the gradual disappearance of cultural and social identity. Perhaps it is time to reimagine our cities as living environments capable of telling the stories of the people who inhabit them. But is it really possible to separate the legitimate desire to preserve the uniqueness and beauty of our urban environments from the broader and more concerning political context that sees a return to past architecture as an expression of a nostalgic civilization? In reality, some popular content creators have already done so: a highly popular X account called The Cultural Tutor, with 1.7 million followers, explained how, after World War II, it was the Soviet Union that created the baroque and antiquated Moscow Metro, while the United States and the Atlantic Bloc favored “democratic” brutalism (to be fair, the Soviet Union also promoted the construction of the infamous “housing blocks” still associated with dictatorship and oppression today), concluding that «There doesn't seem to be a link between "good architecture" and any ideology. Rather, the whole world is a treasury of fantastic and beloved architecture and urban design, waiting to emulated. Old and new, perceived "left wing" and "right wing" architecture, can all coexist. Everybody benefits from better architecture. And, besides, architecture is the only form of art where public opinion should guide it. Because, unlike other artforms, architecture imposes itself on the world — we have no choice but to live and work in buildings. And so all the examples given here, of historical architectural styles recreated in recent decades, should give hope that it is possible for modern and traditional architecture to exist together. It doesn't have to be one or the other — it can be, for everybody's benefit, both».