Without "In the Mood for Love" we would never have had MUBI Wong Kar-wai's 2000 film celebrates 25 years in theatres

This year, In the Mood for Love returns to cinemas for its twenty-fifth anniversary. However, the most beautiful story about Wong Kar-wai's 2000 film brings it back to the small screen—not the television screen, but an even smaller one. It was 2006, and Efe Cakarel was in a café in Tokyo, wanting to watch the Hong Kong filmmaker’s movie but unable to do so, at least not on his computer. He found this absurd. At that time, Netflix already existed, but it was completely different from what we know today: it wasn't just a matter of subscribing and pressing play—you had to order the DVDs you wanted and wait for them to be shipped to your home (it was only in 2008, a year after the launch of MUBI, that Netflix began offering streaming services). These were years of upheaval for the audiovisual industry and, above all, for how content was consumed, but for Cakarel, the issue was even more specific. It was about offering access to art-house cinema, which had no proper place in the domestic entertainment landscape. Thus, starting with the VoD service called The Auteurs, a proto-MUBI was born, funded by Celluloid Dreams, which over time would evolve into the refined platform we know today. More than just an online window into cinema spanning the past and present, MUBI has become an active distributor with the power to acquire and distribute highly sought-after projects such as Queer by Luca Guadagnino and The Substance by Coralie Fargaet.

posters for the extended cut of in the mood for love are insane pic.twitter.com/FglqAsJcfz

— (@taesdawn26) February 12, 2025

But why is the involvement of a film like In the Mood for Love emblematic in the creation of the platform (it is not even the Turkish entrepreneur’s favorite film, which is instead 8½ by Federico Fellini)? Thanks to the platform, people who are distant but share a love for the wonderful art of cinema can find what they seek in a single space for sharing, bridging the distances that, on the other hand, a film like In the Mood for Love renders insurmountable. In Wong Kar-wai’s film, two neighbors, confined within the walls of their homes and forced to brush past each other in the corridors, helplessly witness their growing separation. Not an emotional one, but rather an impossibility of pursuing a mutual attraction that cannot be consummated, sublimated, or even acknowledged, forcing them to observe each other from a distance. In the film’s ending, Chow Mo-wan, played by Tony Leung Chiu-Wai, must leave in search of peace. To finally speak the words that the protagonists never said to each other, and which even at that moment, the audience is not allowed to hear. It is in Siem Reap, at the ruins of Angkor Wat in Cambodia, that the character will finally reveal his secret. His unfulfilled yet reciprocated love for Mrs. Chan, played by Maggie Cheung, entrusted to nature and thus made eternal. Or at least, that is what the confession of a man to a hole in the rock, later covered with soil, makes us believe—sealing his love forever.

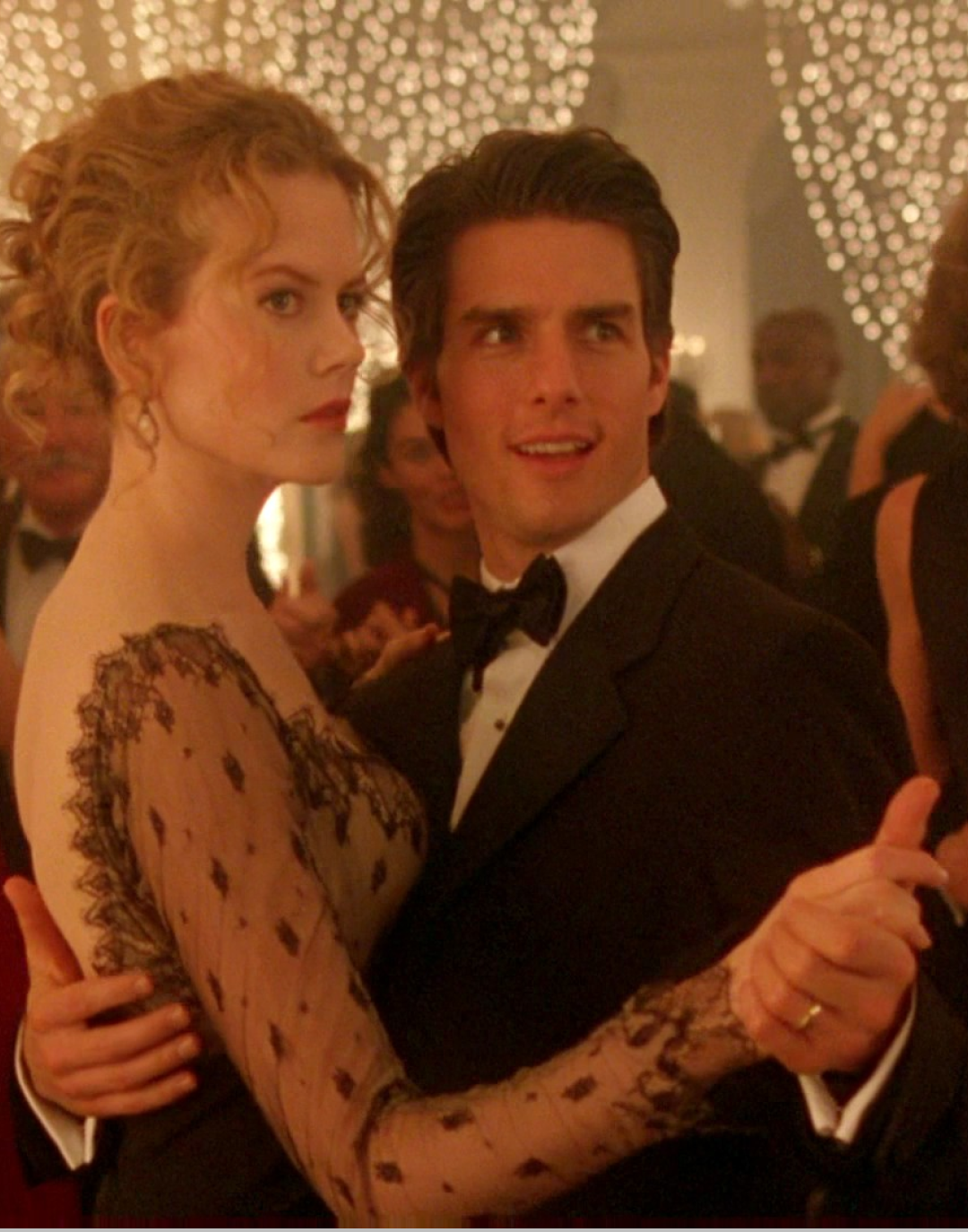

@mubi The dance scene that never made the final cut in #WongKarwai original sound - MUBI

In this story of forced separations, missed opportunities, and a tangibility sacrificed to preserve discretion and propriety, the idea that such a tale helped bridge the gap between audiences and art-house cinema is almost as moving as the film itself. Since 2007, In the Mood for Love has not only been part of Wong Kar-wai’s love trilogy, which began with Days of Being Wild in 1999 and concluded with 2046 in 2004, but has also become part of an entire online auteur cinema landscape. And while streaming today allows us to watch a film at any time, it would be a shame to miss the opportunity to see Wong Kar-wai’s masterpiece projected in theaters in its restored 4K version. A true loss—almost as great as letting love slip away.