If we have sexy vampires today, it's because of “Interview with the Vampire” Before Anne Rice's book, they were just evil monsters

«All the real freaks are seeing Nosferatu and Babygirl» reads a post by X that has circulated across social media, referring to the kind of perversity-tinged sexuality dominating both films. Indeed, despite all its gothic horror, violence, and emphasis on disease and decay, Robert Eggers' Nosferatu has masterfully captured the thematic intersection of love and horror, desire and death that makes the vampire character such an effective and multifaceted metaphor for human nature and its deepest desires. Furthermore, a remarkable aspect of the film is how Eggers managed to perfectly reconcile the original folkloric concept of the vampire with its powerful sexual symbolism—bridging the divide in the vampire fiction genre that had split its portrayal into two streams: on the one hand, vampires as beautiful, romantic creatures à la Twilight, and on the other, monstrous, subhuman vampires like those in 30 Days of Night, Salem's Lot, and so forth.

The first of these representations is today the most canonical thanks to franchises like Underworld, Twilight, The Vampire Diaries, and True Blood, which "domesticated" the vampire, turning it into almost a superhero endowed with powers like super-speed and super-strength, along with a beauty that over time has become less ethereal and more akin to the classic Abercrombie & Fitch catalogs. And while it’s true that ever since its literary debut in 1818 with The Vampyre, this undead figure has been associated with damned, Byronic beauty (in fact, the inspiration for the gentleman-vampire was literally Lord Byron) and a "forbidden," perverse sexuality, there was a crucial cultural turning point that established the aesthetic of the sexy vampire as we know it today. That turning point was Anne Rice's iconic novel Interview with the Vampire, which later became a cult movie in 1994 starring Tom Cruise and Brad Pitt. But let’s proceed in order: when did vampires become sexy?

Very Dangerous, Not Very Sexy

one of the first vampire fictions is Carmilla -a lesbian vampire- which predates Bram Stoker -who was believed to be gay- who wrote Dracula, which in turn was adapted into the 1922 Nosferatu by FW Murnau -who was ALSO believed to be gay

— ambrr (@mbrleigh) January 5, 2025

Queer Nosferatu? I’d say so https://t.co/eMaiaqe3W6

After Austria annexed Serbia and a region of modern-day Romania then called Oltenia in 1718, reports began to spread about how, in those regions, there existed the practice of exhuming corpses to decapitate them and drive a stake through their hearts. Thus, the vampire myth was born, becoming the center of a sort of collective obsession so intense that Empress Maria Theresa of Austria tasked her court physician with conducting what we would now call a debunking operation, which effectively demonstrated that vampires did not exist. However, it was too late, as all of Europe had become fascinated by this myth, which poets and writers, mostly German, began incorporating into their works. Ossenfelder's The Vampire, Bürger's Lenore, and Goethe's The Bride of Corinth are the most famous examples, followed by various mentions in Shelley's immensely popular poetry and the works of Coleridge and Byron. At this stage, the vampire was already as beautiful as it was deadly, but the trio of works that cemented its fame in the 19th century were Polidori's The Vampyre, LeFanu's Carmilla, and, of course, Stoker's Dracula at the end of the century. These three literary cornerstones of modern vampires portrayed them as aristocratic, mysterious, and sexually dangerous: seducers of innocent maidens, temptresses, embodiments of anxieties about homosexuality, destroyers of marriages and families, physical and moral corrupters.

@vintage.lover18 Dracula’s Daughter(1936) | Tags: #draculasdaughter #sapphic #wlw #oldhollywood #horrortok #30s #film #fyp #foru original sound -

The sexual transgression symbolized by the vampire, however, remained trapped in the Dracula archetype. Films like Murnau's original Nosferatu and Dreyer's Vampyr depicted vampires as perhaps aristocratic but deeply detached from society, far from resembling actual humans—let alone handsome ones. Things changed with the 1931 Dracula starring Bela Lugosi, in which the vampire became a "covert monster" with the classic cape and evening attire, though its sensual side remained largely implied and unexpressed. Beyond the literary and TV saga of Barnabas Collins, it wasn't until 1971 that vampires were placed in a realistic, everyday context.

The novel that changed everything was Stephen King's Salem's Lot, a global success, though the vampire there remained a kind of otherworldly monster modeled after Murnau's Nosferatu, and thus far from civilized. During the same decade, a series of exploitation films, mostly French, inspired in turn by the 1936 film Dracula's Daughter, began portraying the vampire not merely as a sexual predator but as a sexual object: 1960's Blood and Roses, 1970's The Vampire Lovers, 1971's The Devil's Vestal, and especially Jesús Franco's Vampyros Lesbos, also from 1971, removed blood and decay to highlight the sexual and "aesthetic" aspects of the vampire. It was precisely in this context that a writer emerged who would forever change vampire narratives: Anne Rice with her Interview with the Vampire.

"Interview with the Vampire" and the Birth of the 2.0 Vampire

In the early 1970s, Anne Rice was in her thirties and a university researcher in San Francisco. She had a daughter who was diagnosed with leukemia and died in 1972, leaving a profound mark on the soul of the future author. A year after this loss, she began reworking a short story she had written earlier, which became the novel Interview with the Vampire. It took three years to get it published. When it was released, it received some negative criticism but soon became a success. Many years later, speaking about the book, Rice said she wasn’t an expert on the subject but had based her vampires on Dracula’s Daughter from 1936: «For me, it established what vampires were, these elegant, tragic, and sensitive people. When I wrote Interview with the Vampire, I drew from that feeling. I didn’t do much research». Indeed, Anne Rice's vampires discarded crucifixes, capes, and evening attire, describing them as immortal creatures, highly intelligent, and endowed with a complex and nuanced morality. They were beautiful and wealthy vampires, leading lives of luxury and pleasure, with the protagonist Louis being practically the only one troubled by murder. Using the author's words, the vampires became «a metaphor for lost souls», essentially becoming solitary romantic heroes.

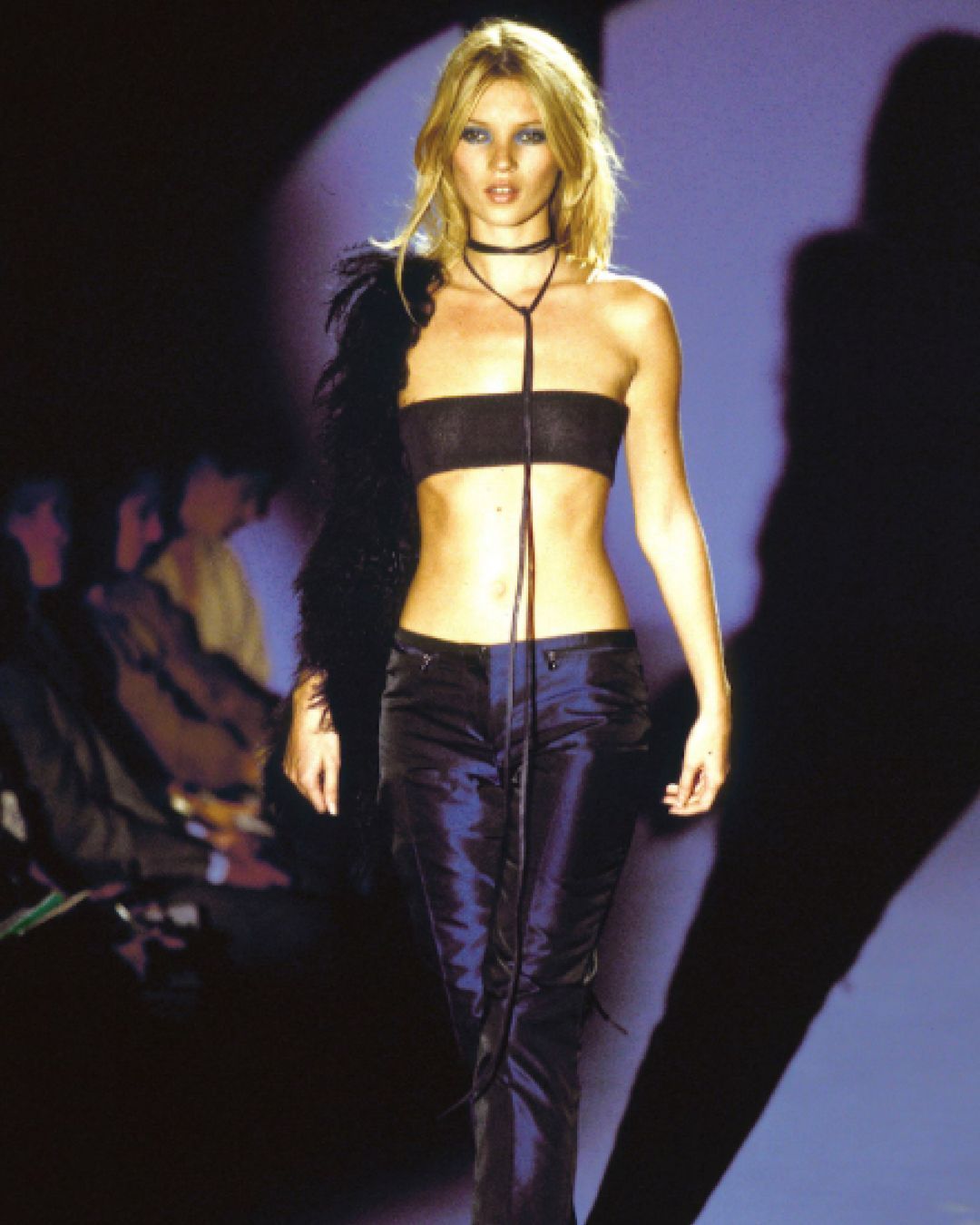

By reversing the story's perspective and making the vampire the narrator rather than the demonic and inscrutable adversary, Rice described their luxurious yet problematic lifestyle, their ability to observe the world beyond the human perspective while blending in with humans. Being a vampire became almost desirable for the reader. For the very first time, the pansexuality of vampires was defined, stemming from their immortality and, thus, being beyond conventional morality, so to speak. Existing outside bourgeois conventions, the two protagonists were the "parents" of the child-vampire Claudia (directly inspired by Rice's late daughter) amidst a story involving emotional and physical relationships with both women and men. For the first time, the vampire's ethereal and androgynous beauty replaced its more macabre aspects; their cadaverous appearance became an aristocratic pallor, and their abilities became akin to superpowers. It’s worth mentioning another novel here, The Hunger by Whitley Strieber, published in 1981, which further humanized the vampire figure and became a legendary film in 1983 starring Catherine Deneuve dressed for the occasion by Yves Saint Laurent.

The Sexy Vampire in Cinema

If we wanted to discuss the modern history of the sexy vampire in cinema, bypassing the erotic B-movies of the '70s, we might begin with the remake of Dracula, which arrived at the end of that decade, in 1979. In this film, Frank Langella abandoned the aloof and detached acting style of Christopher Lee in the Hammer films and created a Dracula very human, very carnal, but also very tied to his era: the first thing we notice today about the character, beyond his healthy and not at all cadaverous complexion, is his teased hairstyle. That same year, Germany saw the release of Werner Herzog's Nosferatu, and the contrast between the two portrayals couldn’t be more striking: in the German film, a faithful existentialist remake of Murnau’s original, the vampire is a kind of outcast, a creep to be pitied. In contrast, the other film presents the vampire as overtly sexual, almost aggressive, bestial. In the mid-'80s, there were the iconic vampire in Fright Night, portrayed as an '80s playboy, and Grace Jones in Vamp!, offering a modern reinterpretation of the dominatrix more than a monster. In 1987 came the first taste of teenage vampires with Lost Boys and the first deconstruction of the vampire myth both as a monster and a sex symbol in Kathryn Bigelow's essential Near Dark.

Finally, we reach the '90s, dominated by a film to which Eggers' Nosferatu owes much: Bram Stoker's Dracula by Francis Ford Coppola, a monumental and hallucinatory remake that pushes expressionism and melodrama to the extreme, also thanks to Gary Oldman, who combines the two sides of the classic vampire: the eloquent and poetic dandy on one hand, and the sub-human monster on the other. Oldman's portrayal, among the most legendary of the genre, keeps the two aspects of the monster separate, appearing in almost every scene in a new form, alternating the man and the monster continuously but never truly blending the two aspects. Two years later came Interview with the Vampire, with its star-studded cast and subtle sense of camp: Tom Cruise’s purple costumes, long wigs, close-ups of Brad Pitt’s chiseled face, and Antonio Banderas’ ambiguous features. The film replicated the atmosphere of Anne Rice's book: these vampires were young, romantic, and, above all, intentionally beautiful—not just attractive like their predecessors but beautiful like models, with a beauty that was vaguely androgynous but indisputable. So beautiful, in fact, that with their plunging shirts, long locks, and intense, languid gazes, it was impossible for anyone to ignore the homosexual undertones (present in the novel but entirely understated in the film), which were absolutely apparent.

The experiment wasn’t immediately repeated: in the following years, there were films in which vampires were purely monsters, as in Carpenter’s Vampires, or metaphors for drug addiction, as in Abel Ferrara’s The Addiction. But it wasn’t until the Underworld and Blade sagas that vampires became more like superheroes—cool and clad in black leather—causing their image to explode in pop culture. By the release of Dracula 2000, the Transylvanian count was portrayed by Gerard Butler, aka Leonidas in 300, while in Queen of the Damned, the queen of vampires was the legendary Aaliyah. Curiously, sexy vampires resurfaced a decade later with Twilight—curiously because in Twilight, the vampires are as beautiful as teen idols but equally chaste, as well as "vegetarian," ethical, and sparkling. It was as if, with their definitive entrance into contemporary pop culture, even vampires had become bourgeois, conforming to social etiquette and blending completely with normal people. Twilight sparked a vampire-mania, followed by The Vampire Diaries and True Blood, as well as films like Byzantium, whose protagonists belonged more to "fantasy romance." This mania created a wave of parodies and more serious deconstructions of the vampire myth that largely overlooked the sexual symbolism behind its legend—a wave that persisted until last December when Robert Eggers’ perverse, visceral vampire emerged from the grave to haunt the dreams of a pale and melancholic Lily Rose Depp.