Streaming platforms are becoming increasingly similar to traditional TV Time to reopen DVD stores

In the American advertising industry, for decades, large ad hoc events have been organized to present new TV channel schedules to advertisers. These events are usually annual, held in the spring, and are called “upfronts”. Here, television broadcasters try to sell advertising spots in their future programs in advance, allowing advertisers to purchase large volumes of ads at more favorable rates compared to last-minute purchases. Moreover, this offers the opportunity to secure ad space in the most anticipated programs. Upfronts originated in the traditional television industry, but with the expansion of the media landscape, they have evolved. This year, for the first time, the two largest streaming platforms, Netflix and Prime Video, participated in the event, a turning point that highlights how the streaming platform economy is returning to rely on traditional business models, typical of linear TV – that is, based on advertising, «the most traditional and least alternative ‘fuel’ of the media industry». This is how Lelio Simi, a journalist who covers the media industry and author of the newsletter #Mediastorm, defines it.

Wow, not only has Amazon Prime video really switched over to their ads model for their streaming platform, they've done it for TV shows that aren't available for normal streaming, or at least weren't when I BOUGHT THEM.

— A.R. Moxon (@JuliusGoat) March 2, 2024

Yep, I'm getting ads on content that I BOUGHT. Awesome.

Aside from Apple TV+, all major streaming platforms have now introduced – by adjusting their subscriptions – a form of advertising. «A simple and effective way to make money», notes Andrea Girolami, journalist, content manager, and author of the newsletter Scrolling Infinito. Although the ads on these platforms are far fewer than on traditional TV, even in this case, the ad-based business model has proven – over the long term – to be one of the most economically sustainable, so much so that it has become essential even in a sector where it seemed to be outdated. «As much as advertising can be defined as ‘that thing people are willing to pay not to see,’ the business model that relies solely on subscriptions or entirely ad-free revenues seems, sooner or later, to show its limits – even for companies like Netflix, which have built vast communities around them,» wrote Simi in 2022 in his newsletter. However, «the advertising model is an efficient model, but not necessarily the most efficient one,» emphasizes Girolami, adding: «Streaming platforms, like any other online business, have had to diversify their revenue streams, taking money wherever they can – subscriptions, advertising, but also sales of merchandise, licenses, or video games.»

@laleggiadro Piantino messo in pausa#netflix #pubblicità #fypシ suono originale - alessia leggiadro

Once a service has established itself in the market, the business models of companies – even large and innovative ones – often tend to become more standardized and traditional. This is exactly what happened to streaming platforms: over the years, they realized that relying almost exclusively on the number of subscribers – however large – was not enough to ensure economic sustainability. «Now that platforms are as big as, if not bigger than, linear television, the audience they target and the monetization strategies are the same, as is the need to do more with less,» says Girolami. «Streaming platforms copy linear TV because it is an industry with production cost efficiency,» he explains. In this context, the introduction of advertising was seen as the most immediate and profitable solution, at a time when the maximum number of people willing to pay for streaming seems to have been reached. «There aren’t that many $10 monthly subscriptions that people are willing to sign up for,» summarized The Economist on the matter. Today, individual companies, rather than aiming to acquire new users, try to steal them from other platforms, retain them, and build loyalty. One way they do this is by no longer releasing all the episodes of a series at once but spreading them out over time to keep the interest of viewers alive. This approach, once again, breaks a famous standard that streaming platforms championed when they first entered the market – in contrast to previous habits. For example, Amazon Prime’s flagship series The Rings of Power, initially one of the most anticipated by viewers, has followed a weekly release model for both the first and second seasons.

Ads on streaming is officially outta control. ads on Netflix? YouTube 50 sec nonskipables. SoundCloud just disrespectful. I saw an ad at the end of a Tik Tok video. I’m pretty sure I signed up for Prime to avoid ads but now I gotta upgrade to a new tier? I should sue somebody.

— Tori Wan Kenobi (@MajestyRia) August 28, 2024

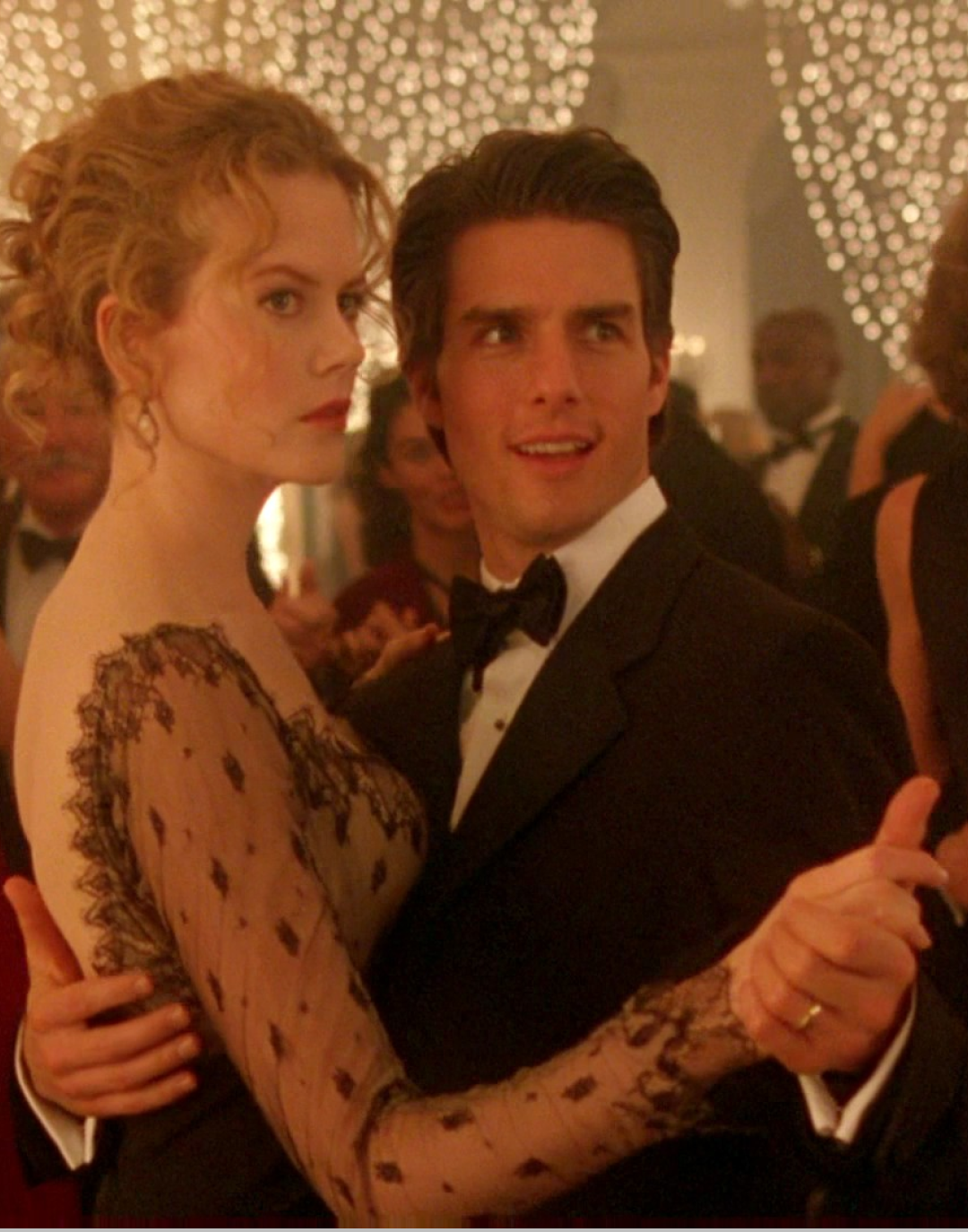

The journey of The Rings of Power also demonstrates another trend: for years, platforms have focused on high-prestige films and series, investing large budgets in the hope of winning awards that would strengthen their reputation in the film industry. «This metric was taken as the main – if not the only – one by large financial investors to assess the value of these media companies, effectively distorting the market and pushing them to spend enormous amounts on new content, beyond any cost-revenue logic,» explains Simi. «As the theory of the notorious ‘technological disruption’ teaches, newcomers always try to do what market leaders snub because it’s not very profitable. Thus, when Netflix entered the market, it did so with prestigious series that no TV network was interested in producing because they were uneconomical. These helped it break into the market and find an unclaimed space,» adds Girolami. When Netflix decided, in 2013, to enter the film and series production business, it was a world to which it was completely foreign: as Simi points out, being ‘in the business’ in that field was crucial, and the competition it faced – Hollywood studios – had been there for over ninety years. Today, with the authority that Netflix and other platforms have gained over time, ambitious films and series make less and less sense, even for them.

“We bundle them. All the streamers, all the channels, one place. People just scroll and choose. Ads pay for the content. Commercials every 10-15 minutes.” pic.twitter.com/A5TAINiFoW

— ʟᴜᴋᴇ ʙᴀʀɴᴇᴛᴛ (@LukeBarnett) August 9, 2024

In reference to the renewed business model, which is more focused on advertising, it has become more important to preserve and update popular programs, films, and series – rather than betting everything on sophisticated products that might only appeal to a niche audience. This is why the catalogs of Netflix or Prime Video, among others, increasingly feature reruns of old successful movies or series. As Simi states, «the focus on cost-revenue balance has led many major studios, including Paramount and Warner Bros. Discovery, to completely rethink their exclusive original content policies: licensing the rights to films and series for a few years brings in more money than chasing new subscribers – especially because it has become harder to do so, precisely because of the vast fragmentation of the market. Hence, the circle closes, and the ‘new’ television with commercial breaks and full of old content increasingly resembles the TV we knew in the past».