Pedro Almodóvar's aesthetics in four films From Pepi, Luci, Bom to The Room Next Door, premiering at the Venice Film Festival

«Red is an instinctive choice for me. Of course, I love the colour red very much. But I suppose I use it because it gives an intensity to the place where you use it. It’s a very expressive colour, and in Spain red also represents life, fire, death, blood, passion and carnations – which is the national flower. From a technical standpoint, if you’re filming a night scene, red will give a certain brightness. Also, this is the reason why all the cars are red in my movies. If you put a red car in the countryside, red enhances the natural colours.»

The first films by Pedro Almodóvar were watched by the author of this article together with her mother, from a red sofa in the house where she grew up. It may sound like a fabricated image, considering the theme we are about to discuss, yet it’s true – perhaps the most concrete proof of how, through the colors and poetry with which he narrates the lives of women, the Spanish director strikes a chord. He manages to do so even when addressing euthanasia, in his new film (his first in English after the short film Strange Way of Life) The Room Next Door, premiering this week at the Venice Film Festival and set for release in Italian theaters in December. Almodóvar's latest project deals with a subtle and divisive theme like assisted suicide through the story of a friendship between women, sharp, courageous (sometimes excessively so) protagonists with startling emotional intelligence. The characters played by Julianne Moore and Tilda Swinton are reminiscent of the Spanish director's early works, albeit Americanized. Even in The Room Next Door, if Almodóvar’s much-loved blood red seems to only nod at the colors of the director's homeland, at sex, and drama, it soon reveals itself as something else – a passionate reflection of the heroines it represents. For understandable reasons, in The Room Next Door we don’t find red as sensuality, but as care; nevertheless, it’s always there on the screen, visually conveying the same pathos that the director imbues in his scripts, leaving the audience routinely unsettled by strong but ordinary women.

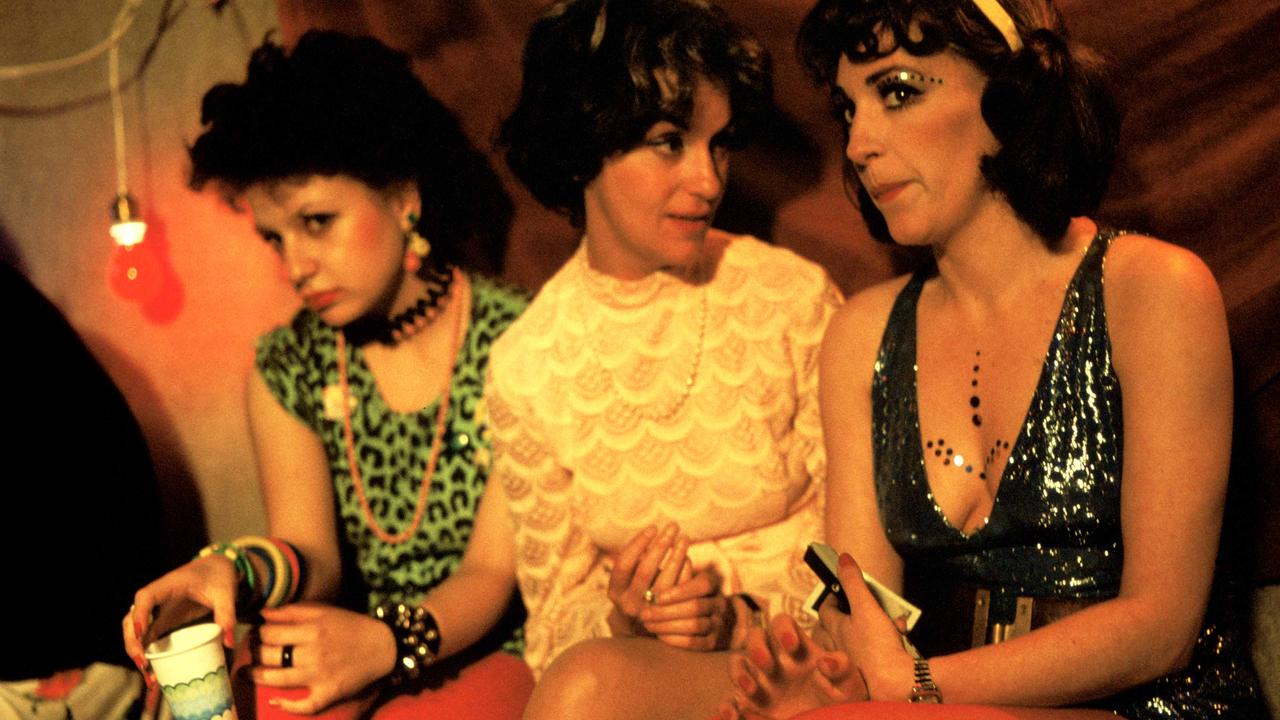

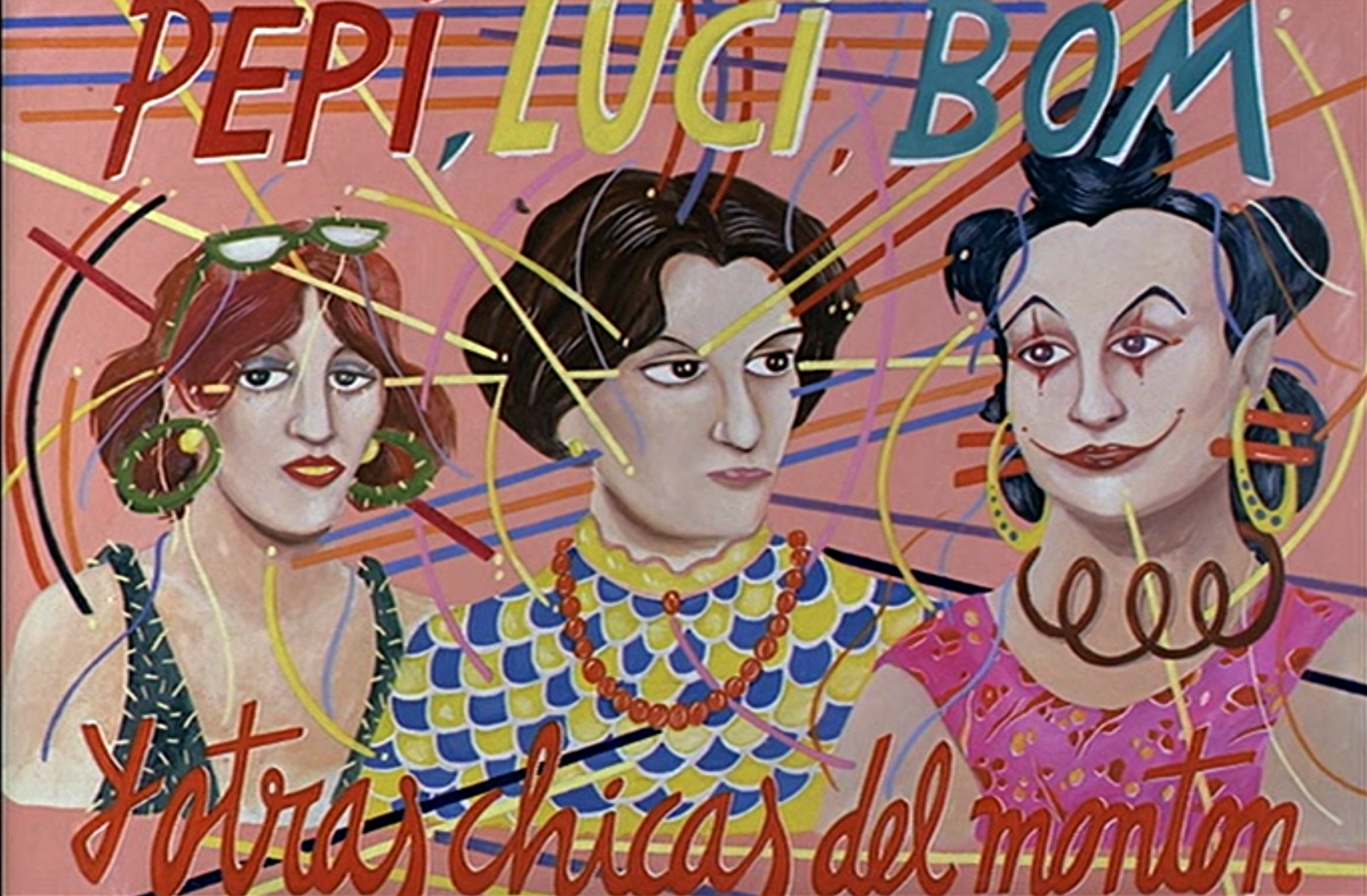

La Movida Madrileña - Pepi, Luci, Bom and Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown

With a career spanning from the 1970s to today, it’s nearly impossible to describe Almodóvar’s aesthetic in just a few paragraphs. One might try starting with Pepi, Luci, Bom (1980), the director's first feature film, completed five years after the end of Francisco Franco's dictatorship, offering a rich preview of all that Almodóvar would bring to the big screen in later years. Telling the story of a friendship between a lesbian punk singer, a protagonist seeking revenge after being raped, and a masochistic housewife, the film's release disgusted critics but struck a chord with the Spanish public, who at the time were hungry for irreverent and camp stories capable of tackling subjects previously censored by the dictatorship. La Movida Madrileña was just that – a counterculture wanting to talk about sex and identity freely, an artistic space where Almodóvar’s aesthetic could form, grow, and expand. While the Spanish director tells the press he found inspiration in the works of Luis Buñuel, Andy Warhol, John Waters, and Alfred Hitchcock to shape his style, for critics, Almodóvar's surrealism has always been unique, describable only by the term almodovarian. How else would you define a film in which an actress prepares gazpacho laced with a sleeping pill for her boyfriend, but it’s drunk by someone else while a friend recounts being on the run from the police because she discovered she was dating a Shiite? Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown (1988) would have captivated audiences with just the protagonist’s stunning apartment («If I’d had the money, I would’ve asked David Hockney to design it,» the director wrote for The Guardian), but between Rossy de Palma’s performance, Carmen Maura’s brilliance, and the duo’s zany story (throw in Antonio Banderas too), the fantastic interior design and the sparkling streets of Madrid almost fade into the background.

Feminism in All About My Mother

After Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown, which earned Almodóvar his first Oscar thanks to a dazzling cocktail of compelling script, intense characters, and striking looks – including polka-dotted dresses, 60s suits, and coffee pot-shaped earrings – the director once again bewitched the world ten years later with All About My Mother (1999). Telling the story of a woman who has lost her adoptive son and sets out to find his biological mother, the film once again focuses on a group of extraordinary women, from a pregnant nun sick with AIDS (played by a very young Penélope Cruz) coming to terms with her fate to a transgender actress who eventually comes to discover the loss of her firstborn. The opening scene directly references All About Eve (1950), a film that inspired this one, as well as the theatricality that characterizes a story full of relevant themes, in the 1990s as well as today. In All About My Mother, drama and comedy intertwine in a blood-red dance that, as always, blazes through the homes and wardrobes of the protagonists: Almodóvar deftly navigates between feminism and the AIDS epidemic with exemplary sensitivity, a masterful exercise that, in 2024, we see enriched and flourishing in The Room Next Door. Already in All About My Mother, years before the film industry questioned the ability of male directors to write female roles, Almodóvar created wonderful characters that didn’t clash but shone in comparison. While others were busy designing a sexy Jessica Rabbit because “I was drawn that way,” the Spanish director tested his understanding of the female universe, proving that for women, the color of blood is not just sensuality but also pain, madness, anger, courage, warmth, and finally joy.

The Room Next Door brings Almodóvar’s new red to Venice

In the last twenty years, Almodóvar’s red has faded, but the importance of the color in the director’s works remains unchanged. In The Room Next Door, it reappears in the clothes, faces, and homes of the protagonists at precise moments, almost to draw the audience’s attention to key scenes where the lines require careful listening. Although his filmography is less kitschy than before, more polished and orderly, we find in every stylistic choice the same Almodóvar from All About My Mother: a creator obsessed with women’s emotions and their representation in the form of clothes, sofas, and ironic remarks. Today, Almodóvar’s surrealism has found space in luxury thanks to Saint Laurent, which designed the costumes for Strange Way of Life, and Loewe, with Jonathan Anderson crafting the looks worn by the director of The Room Next Door at the Venice Film Festival. But his universe continues to speak to the same audience as always, made up of ordinary people with extraordinary lives: women who try to make their boyfriends faint with drug-laced gazpacho, women who swear allegiance to God but find themselves pregnant by a mortal, women who watch a movie with their mother from a red sofa, and finally, women who suggest their daughter do the same, from that very same red sofa.