Not everyone is going to like "Queer" Luca Guadagnino's new film that teaches cinema how to respect literature

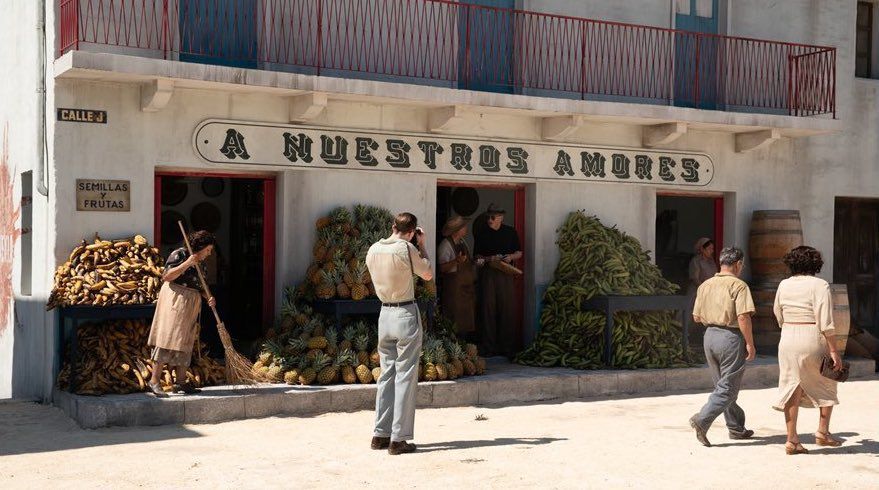

«You are not queer.» This is the first line spoken by the character played by Daniel Craig in the new film by Luca Guadagnino, Queer, written by Justin Kuritzkes—already the screenwriter of Challengers—and based on the novel by the notorious William S. Burroughs. It's the story of a man struck by a young man whose admiration is not reciprocated. So, if the boy to whom Lee refers is labeled as not belonging to the category the film constantly refers to—a "curse" the protagonist speaks of and that seems to have afflicted his family for generations (i.e., being homosexual, a term that, when uttered in the film, causes an extra to flinch)—Guadagnino's film is one hundred percent so. Not just (not only) because of the sexual orientation of Lee's character, but for the faithfulness maintained with the novel from 1985 (for money, not by choice), set in a fictional Mexico, into which the life of the American writer is forcefully inserted. As he himself has repeatedly recounted, the book is Luca Guadagnino's favorite; for this reason, unlike his homage to Suspiria inspired by Dario Argento's horror cult, the director does not chew up the original work to the point of spitting it out in a completely different form.

First clip of Drew Starkey and Daniel Craig in Luca Guadagnino's 'QUEER'.

— Drew Starkey Updates (@DrewStarkeyUPD) September 3, 2024

Premiering today at the Venice Film Festival. pic.twitter.com/VMFR00tD21

In the film adaptation of Queer, Guadagnino rigorously respects every page, emphasizing a fidelity that comes from the opportunity to see his favorite novel on the big screen, so much so that he adds at the end the signature «William S. Burroughs’s Queer» instead of the director's. This is a significant detail, especially for those who may find the work very different from the rest of a cinematic corpus that has chosen to be chameleonic, never conforming to a single cinematic genre. Although always signed with the "Guadagnino" tag, each of the director's films has revealed itself over the years to be different from the previous ones. There was the aforementioned horror, the bourgeois drama, the absolute pop. And even when the spirit might seem the same, from the coming-of-age story Call Me by Your Name to Bones and All, the author veered toward a deliberately more romantic soul, tinged with blood and surrealism. This time, with Queer, Guadagnino places himself between the metaphysical of David Lynch (but even more towards the carnal and transformative search of cinema) and the monstrously physical of David Cronenberg.

Cronenberg himself, in 1991, made another film based on Burroughs's works: Naked Lunch, which is also repeatedly referenced in Queer with centipedes and typewriters, underlining the intention of Guadagnino and his collaborator Kuritzkes to create a cinematic compendium of the beat writer's work. Moreover, they sought to introduce into the film the very life of William Burroughs and, in turn, the interchangeability of his literary work, which constantly communicated from title to title, novel to novel. It is well known that his first book, Junkie (originally released as Junkie), lacked pages to be printed, so Burroughs added a part initially written for Queer to complete it. Similarly, Guadagnino takes Cronenberg and mixes Burroughs' existence, the trauma around which the rest of his days revolved (the accidental killing of his wife Joan, present here and in Naked Lunch), and concludes the film by transcending the novel itself, halfway between the metaphysical and the biopic, as if it were set in the Interzone that so frequently punctuated the author's writings (itself a collection of stories from his early works from 1953 to 1958). Queer becomes his personal 2001: A Space Odyssey, where time passes quickly, retracing key events of his life, with an aged Lee/Burroughs, a man predicted to have a short life due to excessive drug use but who instead lived to a ripe old age.

QUEER takes sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll to a whole new level. Full of steamy love scenes and an audacious vision, but one that'll be extremely divisive. It’s Daniel Craig like you’ve never seen him before, and a star-making moment for Drew Starkey pic.twitter.com/CIEmXf3lJJ

— Ema Sasic @ Venice (@ema_sasic) September 3, 2024

With his new project, Guadagnino presents the viewer with a clear and transparent picture of a filmic text that is not easy to read, for those who do not possess the key information to decode its images, a detail that creates the greatest disparity between those who might love and those who might hate the work. If one is not familiar with Burroughs's biography and background, one must do some extraction work, move away from the idea of a linear narrative—which does not necessarily have to lead somewhere. Or, better yet, like with yage, the drug Lee and his love interest Allerton search for in the jungle, what one should expect is to find oneself facing a mirror to look into, accepting any reflection that is returned, especially if unexpected. However, if one comes to the theater with the necessary—but not mandatory—tools, as the enjoyment of a work should remain regardless of pre-existing knowledge about it, Queer reveals Guadagnino's admiration for the writer's vision, the craving for experimentation, the fusion of bodies eager for contact, like the search for a drug to activate telepathy and finally find a way to connect with others in a primordial, deep way, without words. Lee's desperation to be loved by Allerton and the tragic end of a relationship that never began.

@loewe Daniel Craig, Luca Guadagnino and Drew Starkey in Venice attending the premiere of Luca’s new film “Queer” wearing custom #LOEWE. #Queer #LucaGuadagnino #DrewStarkey #DanielCraig original sound - LOEWE

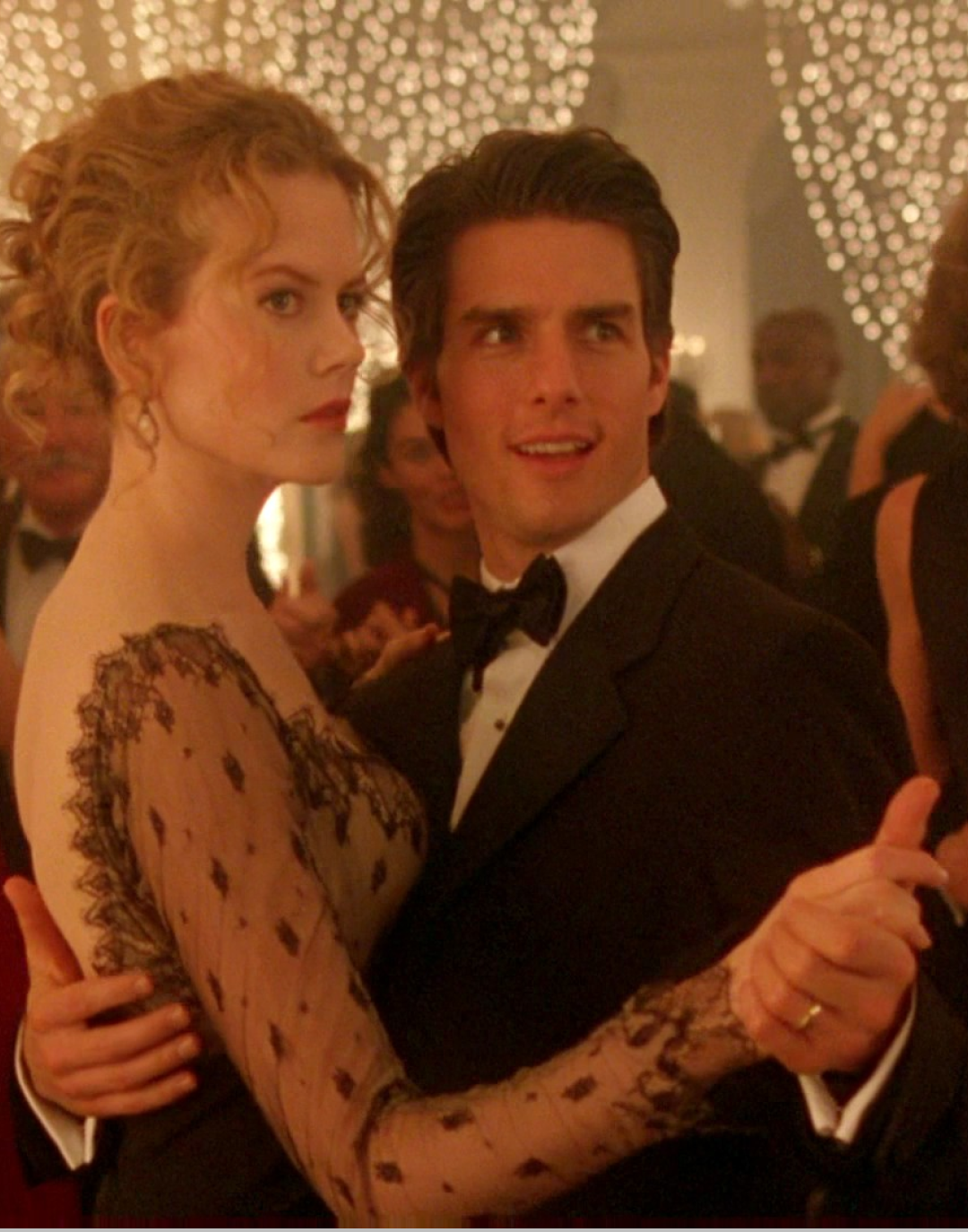

In Queer, Daniel Craig is histrionic, although the description of Lee in the book could have allowed for even more. The character possesses a fragility that belongs to someone who is alone in the world and finds in sex (little, too little, unfortunately, as most of the erotic scenes have been cut) a way to establish a connection—often weak, certainly shallow, destined only for the time of an evening or a motel rented by the hour. A round of applause to Drew Starkey, who makes a quality leap from the series Outer Banks, transfiguring body, face, and silhouette, carefully wrapped in the costume design of Jonathan Anderson, creative director of Loewe and his own eponymous brand. A further step forward for Guadagnino's direction, Queer is halfway between biography and fiction, between this world and a very distant one. It’s an invitation (you can hear Nirvana during the first exchange of glances between Lee and Allerton with Come as You Are, practically a prompt) not to be afraid of taking a potent aphrodisiac, in this case, cinema, and to let oneself be overwhelmed by its effects.