Eric and the depth of the human soul The new Netflix miniseries hits the mark without second seasons

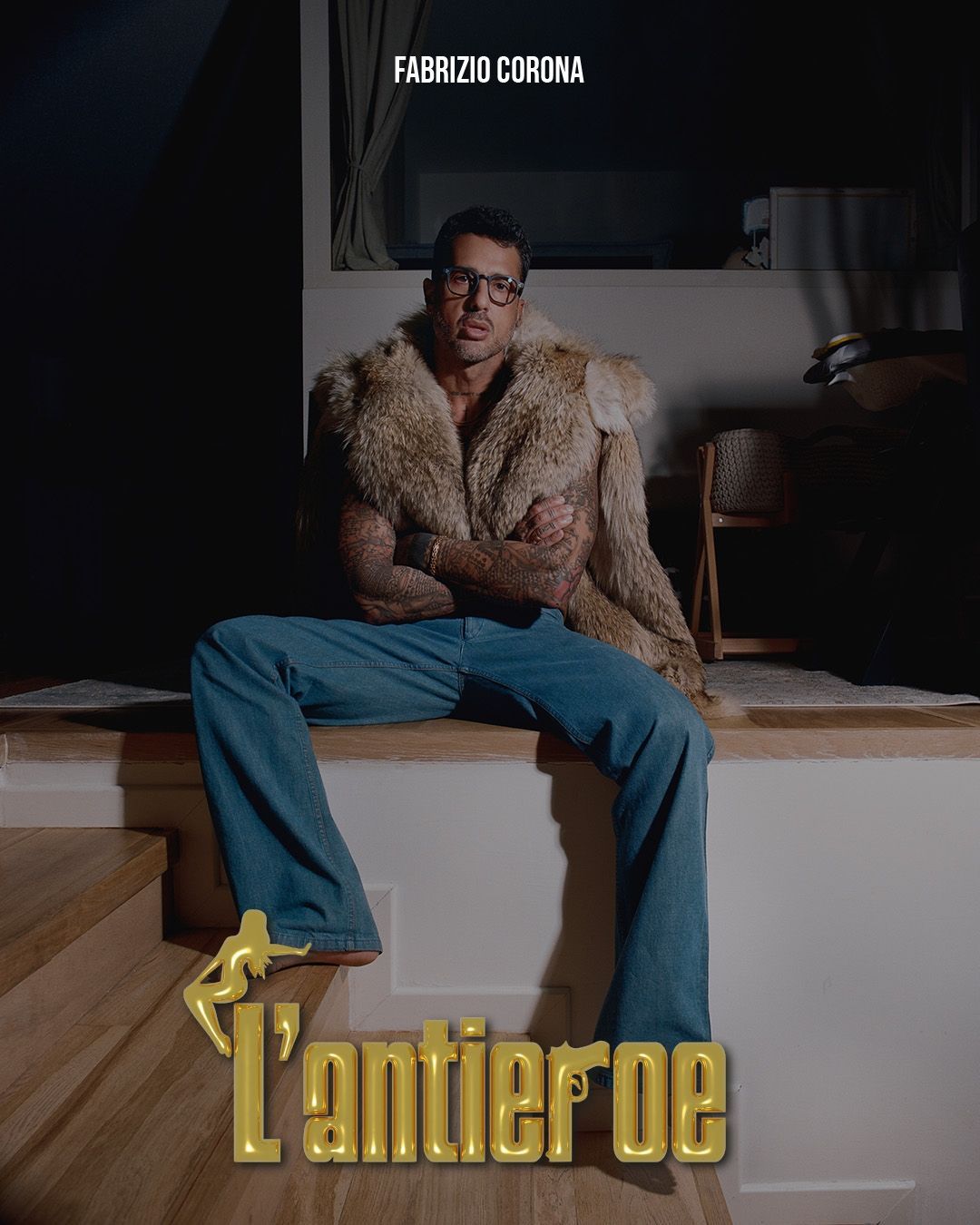

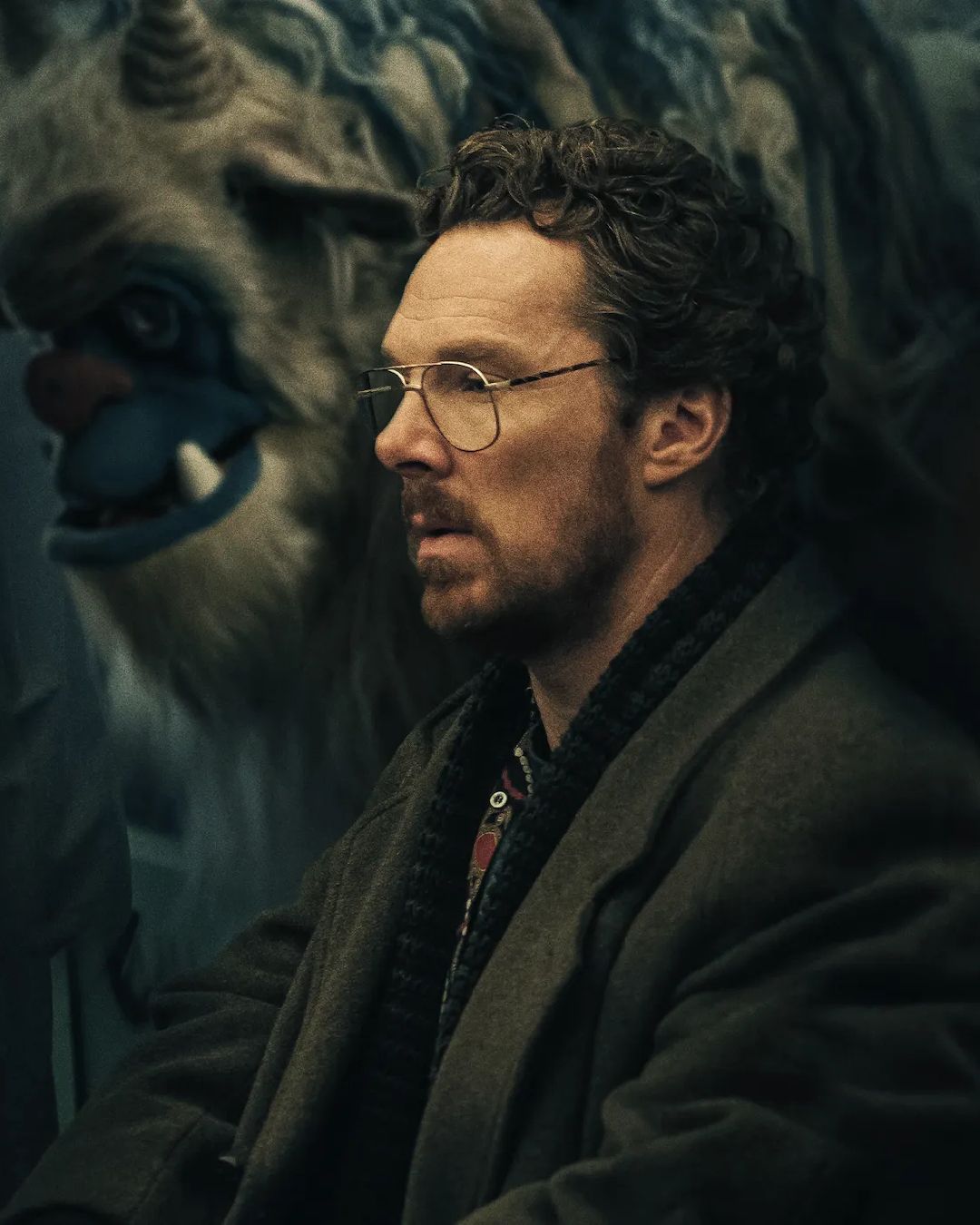

Not everyone will have seen If, a film by John Krasinski who tries his hand at the family movie genre in mixed technique, after having asserted his status as a director with the "silent" horror film A Quiet Place in 2018 (and with the sequel released a couple of years later). A few weeks after the release of the film, which tells the story of a girl and her neighbor (Ryan Reynolds) who must find new children to assign old imaginary friends to before they disappear, Netflix launches the counterpoint to all the fantasies of the little ones - those that usually hide under the bed - with the miniseries Eric. Starring Benedict Cumberbatch, created by Abi Morgan and directed by Lucy Forbes, Eric is the perfect example not only of how there are products on the streaming platform that don't have to be dragged out for eight seasons, but also of how with a good story you can indulge the public's pleasure much more.

Set in 1980s New York, in a neighborhood that wants to be decent but only hides its dirt under the rug, Eric takes its title from the puppet/imaginary friend with whom Vincent (Cumberbatch) begins to interact. A father who has lost his son Edgar (Ivan Morris), Vincent hopes to find him again by bringing the little boy's invention to his children's show, Good Day Sunshine. In the series, Eric is therefore a puppet with a double meaning. For Edgar, shy and introverted, he is a bridge of communication with the outside world, as he is tired of the shouting in a house where parents have no other way of talking except to pour resentment on each other. For Vincent, on the other hand, the puppet becomes the only hope, sometimes crazy and unbalanced, to get closer to the son he himself was the first to push away. Guilt pushes the protagonist beyond modesty, beyond sanity, beyond the heart, making him isolated and lonely, even more aggressive and surly than usual, as he investigates, building castles in the air that have the shapes and architectures of the dirty Big Apple. In Eric there is not only the story of the disappearance to compete for the center of attention, and not even the addiction to alcohol and drugs that gradually begins to cloud the parent's mind - as well as accentuating his already suspicious and arrogant character.

The miniseries chooses an overflowing structure that surprisingly holds up well all the elements in play: there is the storyline of the policeman following the case, an African-American homosexual in an era when AIDS was rampant in the streets; there is the corruption in his own station, where it is not too surprising to imagine some colleagues with dirty records; there is a nightclub, the Lux, where the city's perversions meet. Then there is the theme of the parent-child relationship, complex whatever the role one finds oneself in (both between Edgar and Vincent, but also between Vincent and his millionaire father). And then there is the politics, businesslike and hypocritical, which wants the streets of New York clean and the homeless thrown into some dumpster, as far away from the decent neighbourhoods as possible. And it is precisely on "decent" that Eric focuses, between respectability, careerism and opportunism. As Vincent sinks into a spiral of madness, fueled by rivers of alcohol and prey to a fervent psychosis that brings back demons from the past, the story around him is like a map on which the viewer must try to get around, following as many twists and turns as the story is ready to give. It is then obvious that each path is destined to merge, and then return to the central point: the search for Edgar. On this network of connections the miniseries moves like a tightrope walker, and it hits the mark in being able to keep a clear eye on everything. Nothing is lost, nothing is left behind. We want to go deep into the bigger picture that the creator Morgan wanted to lead the observer to, bringing the monsters out of the closet and asking the audience to follow them, even into the sewers.

Not a work that we will remember as the most exciting of 2024, nor as refined as Ripley or as shocking as Baby Reindeer, Eric is, however, yet another example of how, instead of aiming at expansionist seriality aims, the short format manages to hit the mark. By focusing on a narrative with no leads left open, even though it is full of inputs and suggestions - neither the disappearance of the child, nor the fate of the policeman who still believes in the ethics of his work, nor even the microcosms that Vincent saw swirling around his existence, private and professional, as it fell apart. Not making, in short, a second and often obsolete season the necessary solution. With her miniseries, Abi Morgan shows how the deterioration of one's ‘self’ is the first step towards the collapse of the life one has striven to build for oneself, losing one's compass in a city that leaves no escape, but which has tales to offer, including murky and complicated ones, and which can speak to a wide audience. Because if it is true that the motto of Vincent's Good Day Sunshine is «Be kind, be brave, be different», sometimes «stay simple, yet effective» can be equally compelling advice.