Why we should watch "The Young Berlusconi"? Brilliant, nostalgic, haunting

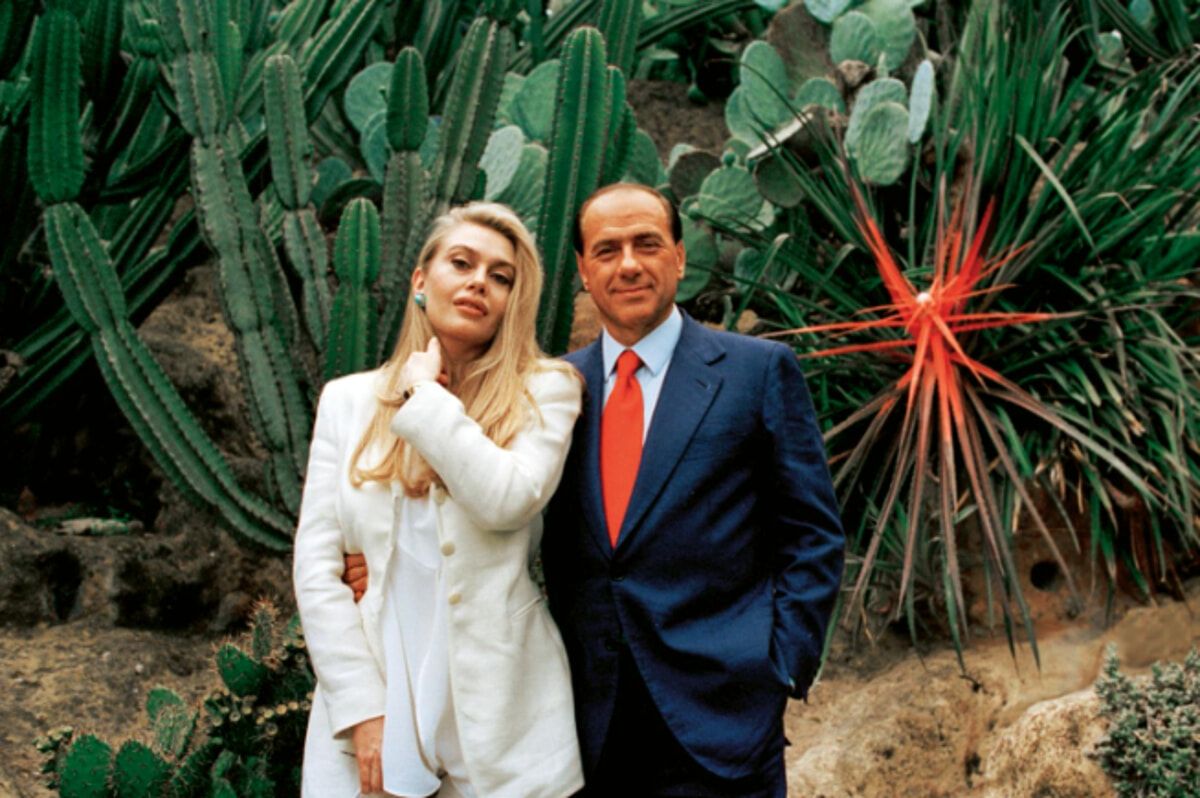

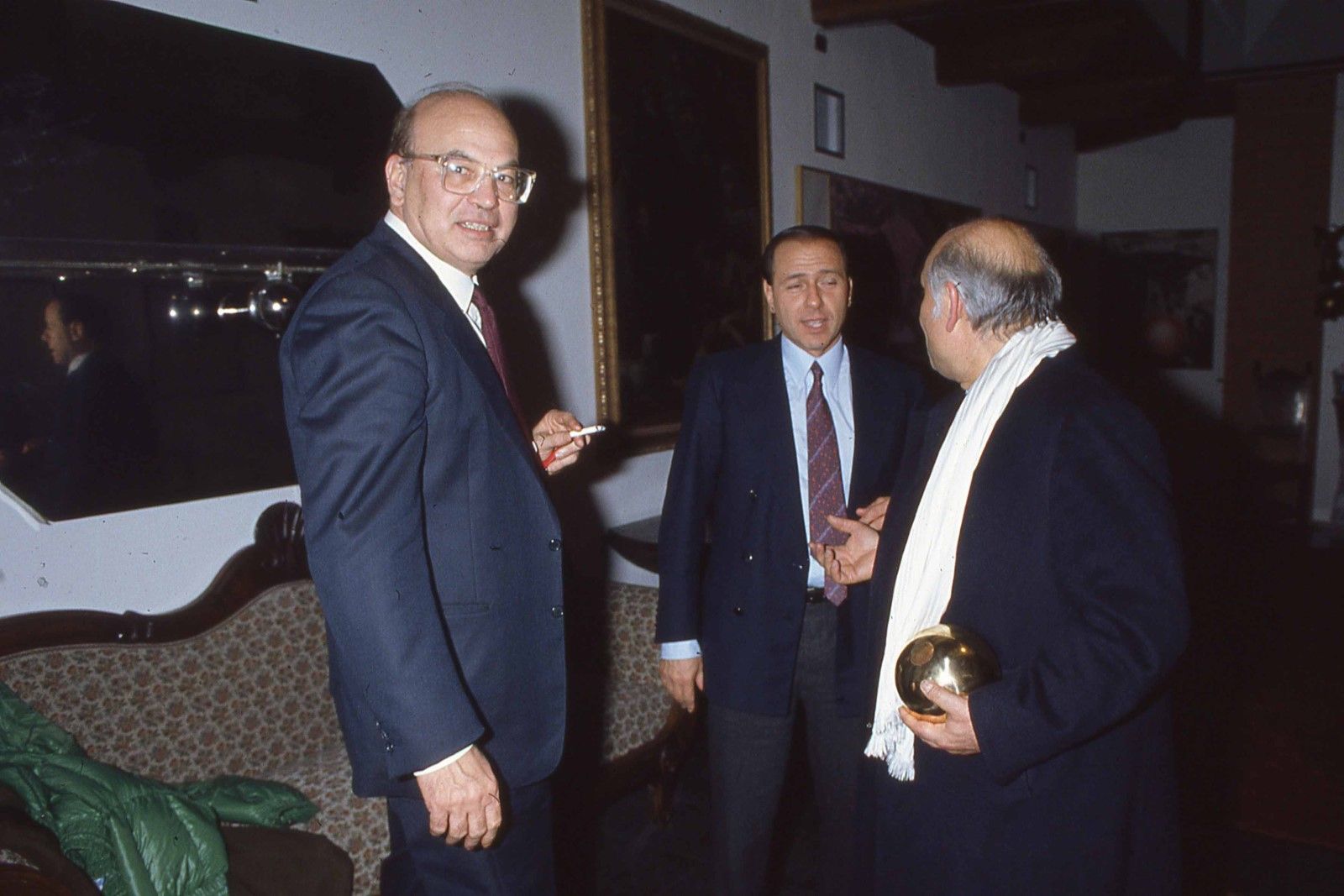

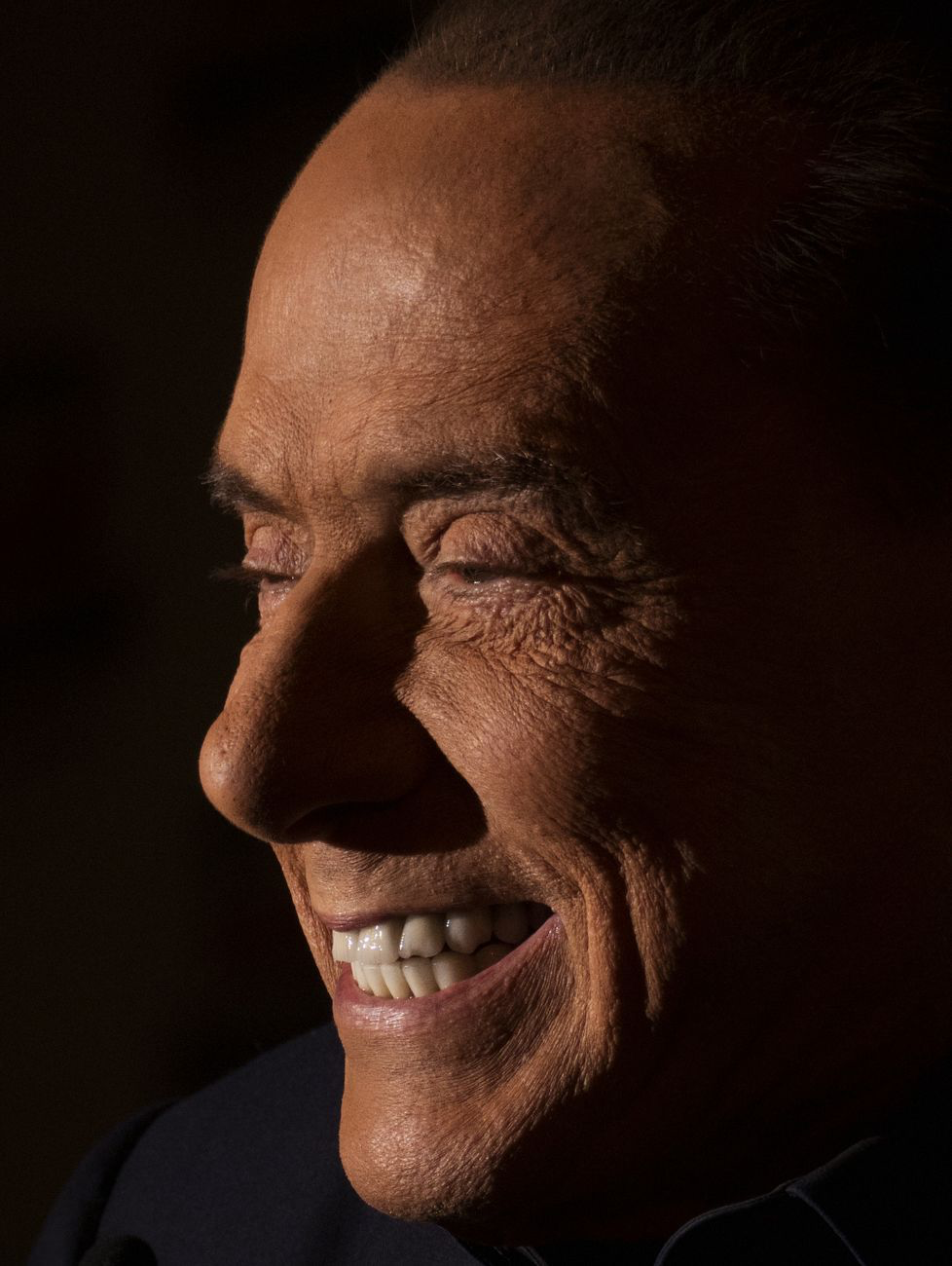

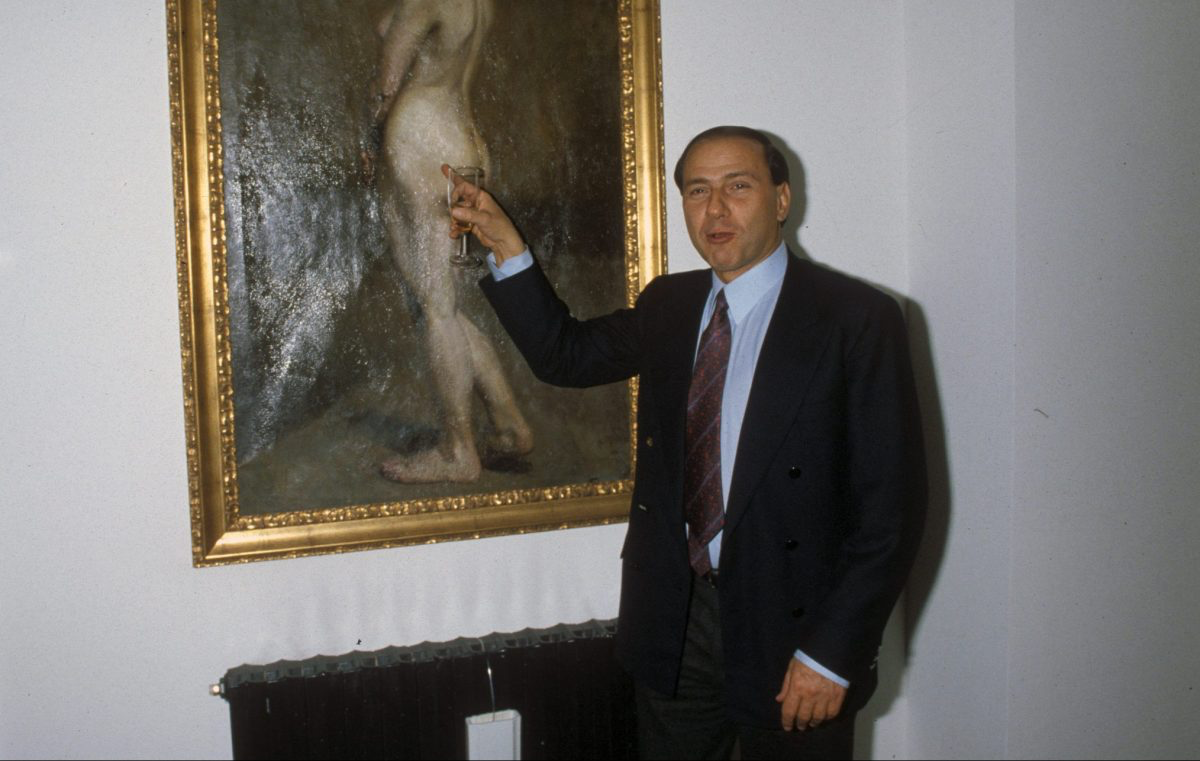

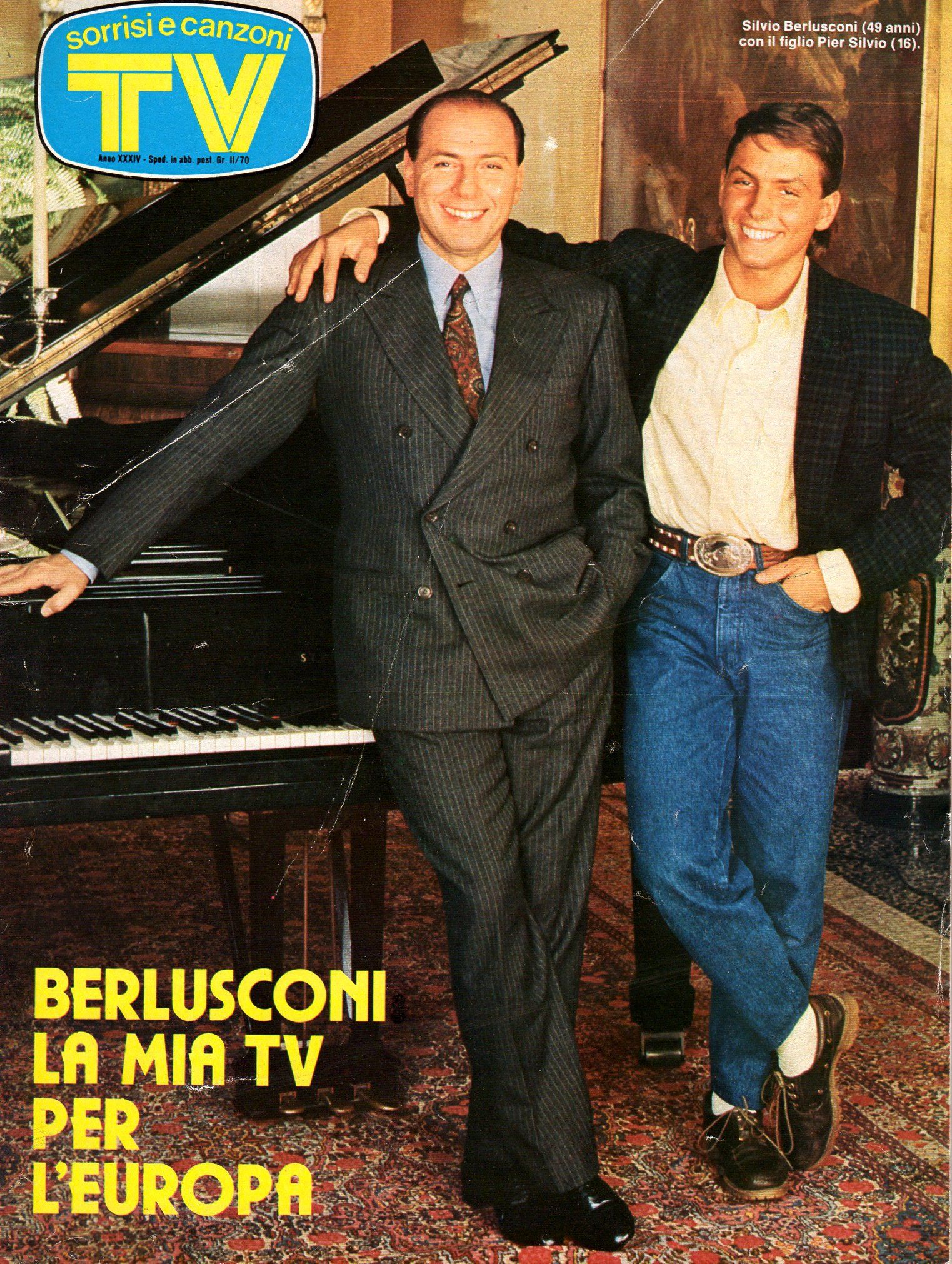

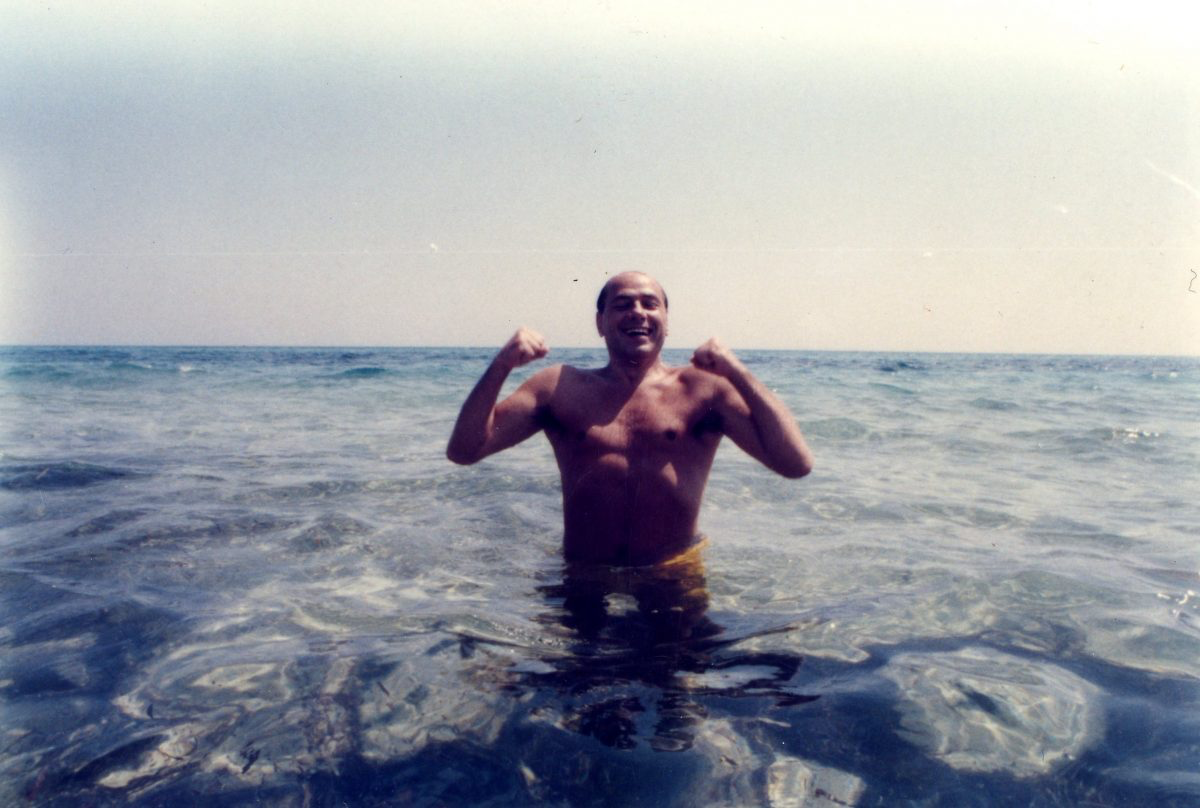

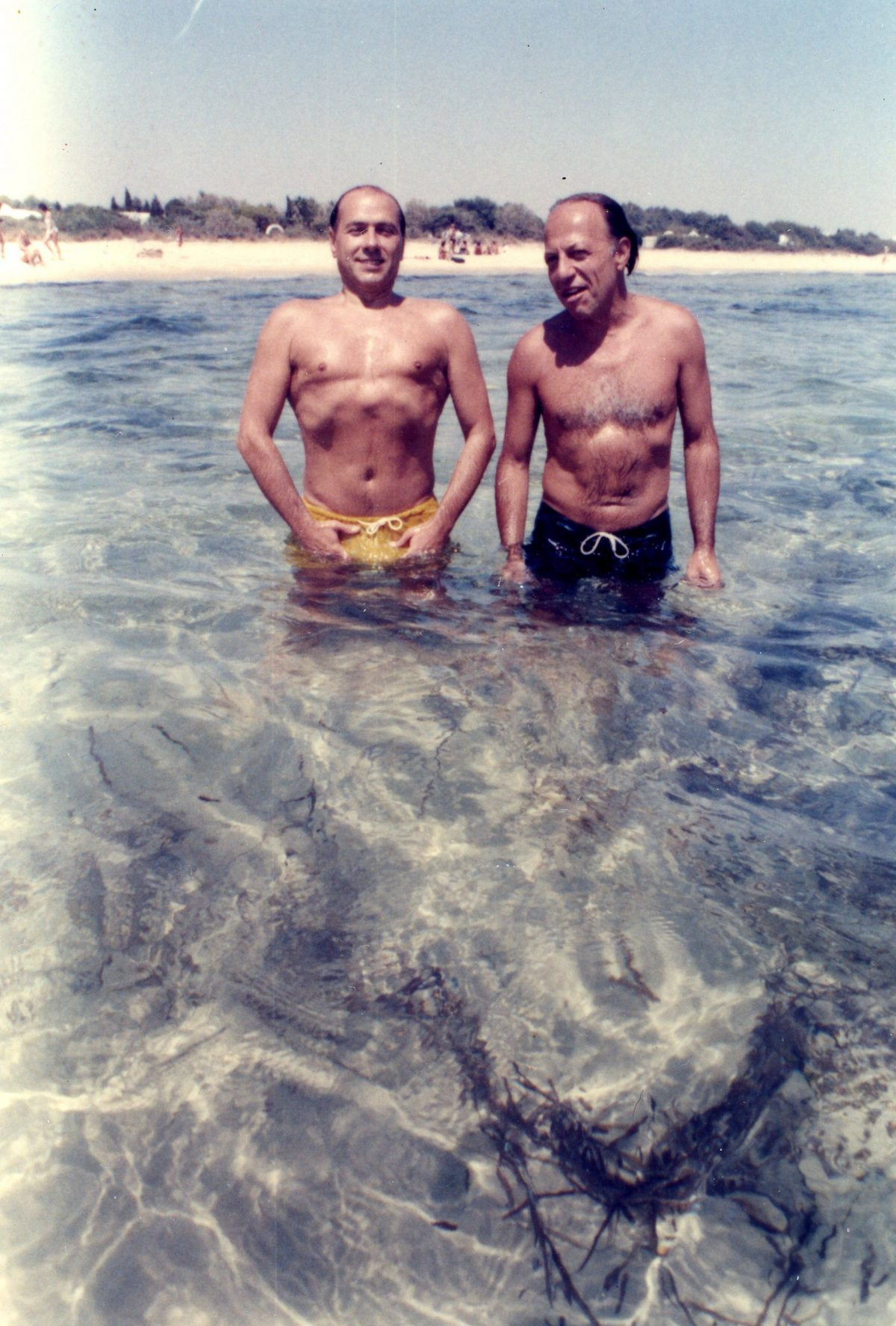

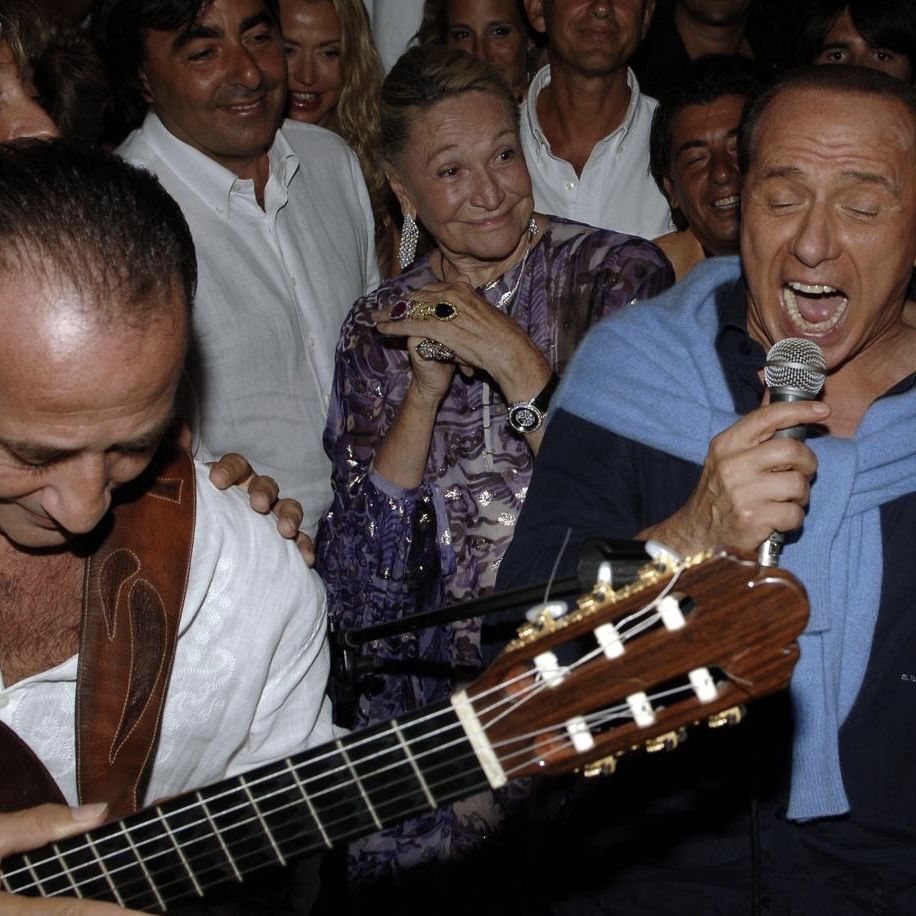

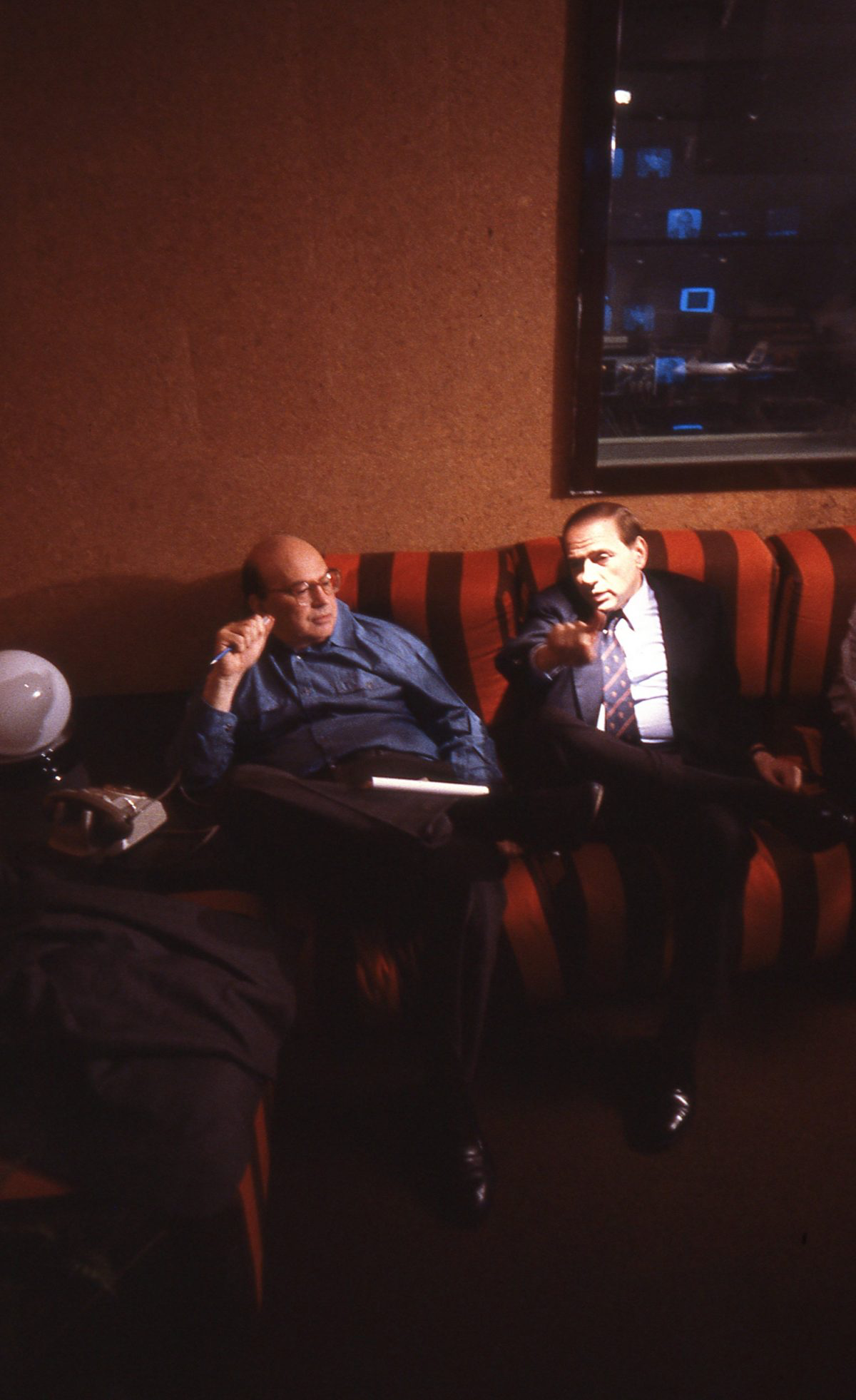

During the three episodes of The Young Berlusconi, the new Netflix docuseries that reconstructs the entrepreneurial trajectory of the most controversial politician in the history of this country, there is a subtle undertone felt behind the enthusiasm of the narrative. The story, which begins in the 1970s with the acquisition of the first local television networks and the birth of Milano 2, then unfolds through the yuppie triumph of the 1980s with Mediaset and AC Milan, concluding finally with the birth of Forza Italia, is one of unstoppable success, brilliant and miraculous foresight, but above all it is a snapshot of a society caught in a historical turning point. In this success story, much like in Villeneuve's Dune, behind the almost messianic figure of the Cavaliere, one glimpses that of the manipulator, one senses in the background the role that rhetoric of disengagement, hedonism, and unscrupulousness would have on the current state of democracy and today's culture of post-truth and post-ideology. Just as Berlusconi anticipated the zeitgeist of the twenty-first century, a society where everything is content, commodified, and spectacularized, the story of his entrepreneurial strategy and his Shakespearean conquest of power anticipates a world like ours, where political propaganda becomes subtler and more insidious the more openly it is in its intentions. In this sense, Berlusconi's radical difference from the rest of the previous political class (an entire episode revolves around the fall of Craxi and Tangentopoli) appears both historically necessary but surreal: one of the most absurd yet strangely truthful moments of the show is precisely when Canale 5 was shut down but the population actually protested to get back their television programs including, unbelievably, The Smurfs. A bizarre situation, almost laughable, but one that speaks well to the stagnation of official culture, the desire for change and modernity in the country, but also the substantial frivolity and superficiality of an electorate that, fundamentally, clamored only for bread and circuses.

The point is precisely this: at that time, state television as well as the state itself in the people of its politicians, its parties, and its politics were tragically antiquated, ossified in positions held for decades, unable to effectively follow the dictates of modernity. Considering that moment, the arrival of Berlusconi's networks, his visionary projects of Milano 2, the purchase of Milan which in a more friendly and popular version mimicked the aristocratic aloofness of the Agnelli clan, the change brought by the various Mediaset, Publitalia, and so on was miraculous. A breath of freshness that practically obliterated the obsolescence of an official culture, eventually replacing it – but irreversibly lowering the tone of public discourse. That same saving grace, that radical modernity, however, paved the way for product placement, semi-hidden propaganda, the overwhelming power with which the media still hold the collective consciousness by the throat today. Towards the end of the second episode and throughout the third, a moment of crisis is then recounted which will retrospectively represent the culmination of Berlusconi's trajectory: the almost simultaneous collapse of the Berlin Wall, of Craxi, of the entire political system with Tangentopoli, the indebtedness and the misguided investments. Here comes the twist: from cornered alpha super-predator, Berlusconi gambles everything and leaps into the political world, further raising the stakes but winning it all. From then on, politics would become pop culture, parties akin to corporate machines, official communication and expedients to gain consensus theatrical. It is the birth of the modern world – but at the end of the series, this birth is closer to The Omen and Rosemary's Baby than to a simple "happy event".

Berlusconi was the prophet of a society happy with its wealth, enthusiastic about its own vitality and yet spoiled at the terminal stage, drugged with a superficiality and joy that were beautiful then but today have had other and heavier consequences. Exploring this society, the change in that world from the "high" perspective of Berlusconi is perhaps the most important value of this series which, let's say, is neither a hagiography nor a lamentation, but the lucid account, between joy and dystopia, of a winning ruthlessness.