Could Naples have been Venice? Yes, at least in the mind of a recently rediscovered visionary architect

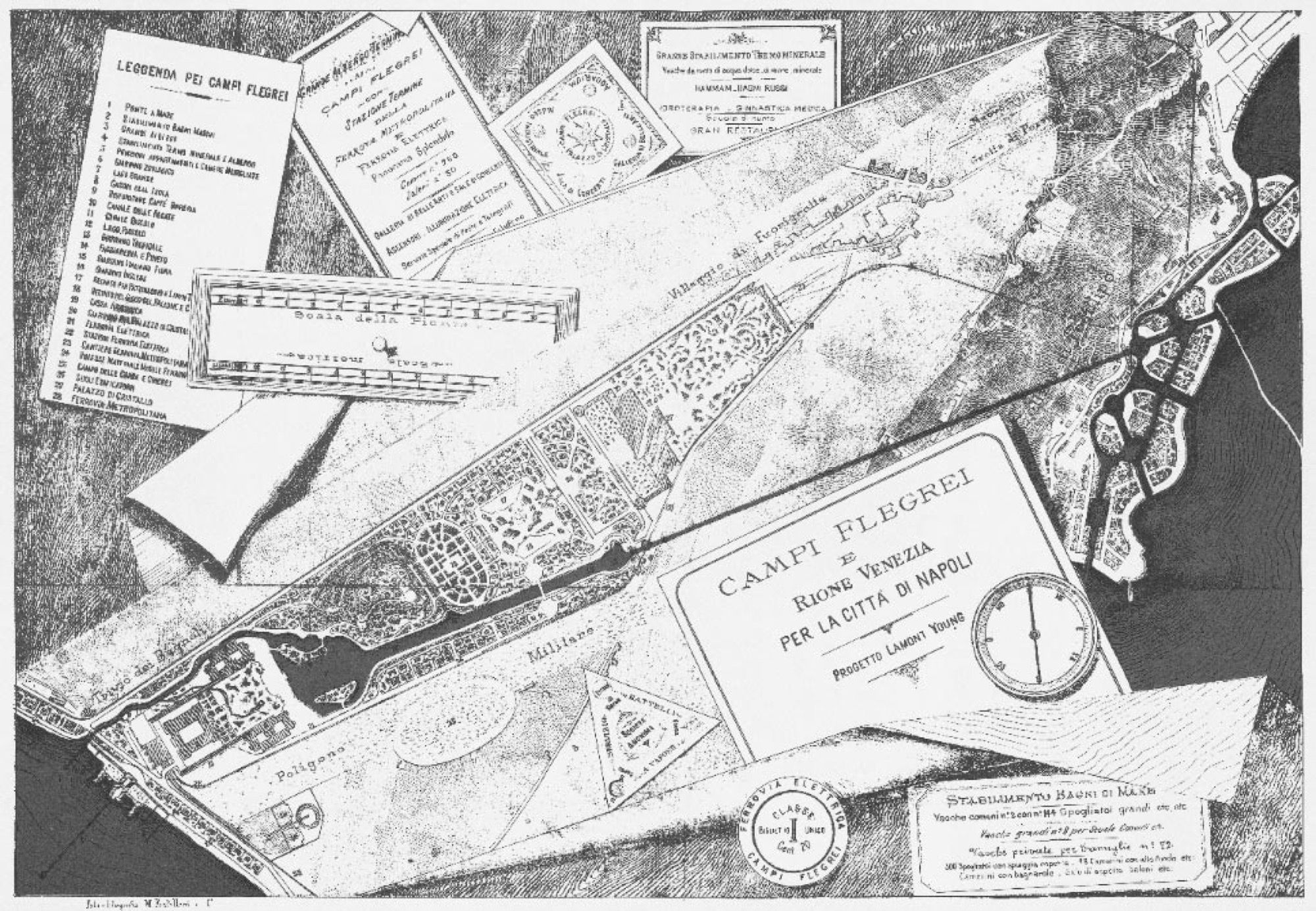

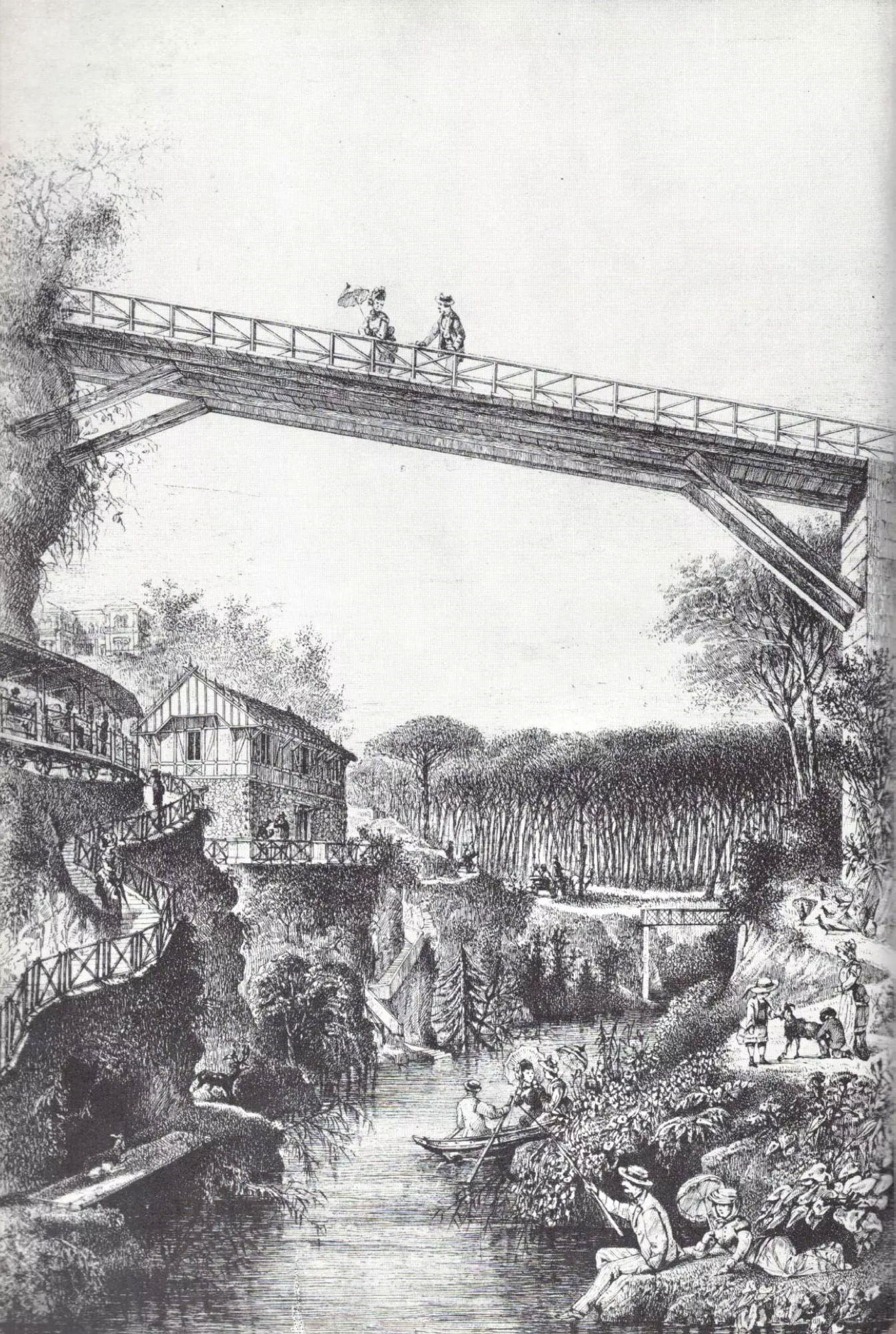

At the end of the 19th century, many urban planners and architects were contemplating the direction in which to develop the historic center of Naples. Among them was the visionary Lamont Young, whose ambitious city expansion plan, never initiated and long forgotten, envisioned the construction of a new neighborhood in the sea, aptly named Rione Venezia. The project aimed to create a series of islands near the Posillipo hill in the western part of the city, covering an area approximately one and a half kilometers long and an average width of 280 meters. According to Young's calculations, the entire neighborhood would have occupied an area of about 425,000 square meters, with 144,000 dedicated to streets, 100,000 to navigable canals, 70,000 to gardens, and 111,000 to buildings. The buildings would have covered just over 26 percent of the reclaimed sea area, ensuring that air circulation followed the Gulf currents from the eastern to the western area, theoretically providing better results than in Venice. The road infrastructure was also quite innovative, featuring streets connected by iron bridges. The distance between buildings was not to be less than eight meters, and the canals had to be at least 12 meters wide. In the vicinity of Rione Venezia, Young also planned to construct baths, hotels, a small port, and bathing establishments.

Who was Lamont Young?

Born in Naples in the mid-19th century but of British nationality, Lamont Young spent much of his life in Naples, yet he never acquired Italian citizenship, despite growing up there and being recognized as a Neapolitan. Recently rediscovered, Young was an architect and urban planner who designed several villas and castles that still grace the Neapolitan landscape. Among his works are Castel Grifeo, now known as Villa Curcio, and the women's school that became Palazzo Grenoble, the home of the French Institute in Naples in 1933. His signature can also be found on the Bertolini Hotel on Corso Vittorio Emanuele and Villa Ebe at the top of the Pizzofalcone ramps in the San Ferdinando district. Young also designed some buildings to be constructed in the Bagnoli plain, such as the Crystal Palace, an ambitious project to showcase the city that was never realized. In 1874, Young, a staunch advocate of mass transit, participated in a competition organized by the city administration for a new horse-drawn tramline, and even though he didn't win, he continued to support the project in the subsequent years. Young passed away in Naples in 1929, but the circumstances of his death and his burial place remain unclear.

Rediscovering Neapolitan Architecture

At the beginning of the 20th century, the Naples City Council reconsidered the construction of Young's Rione Venezia. The formal approval of the project was even reached, and the architect sought private investors to bring it to fruition. However, he was unable to gather the necessary resources, and the idea was ultimately abandoned. Alessandro Castagnaro, a professor of architectural history at the University of Naples, argues that Young was very, perhaps too, ahead of his time. His ideas anticipated many architectural trends that would later become prominent in Europe, and although he had a utopian vision, he was talented and forward-thinking, particularly in the field of transportation. In the decades following his death, Young's architectural legacy was almost entirely forgotten, and even today, he remains a relatively unknown architect, even in Naples itself. However, in recent years, there has been increasing attention to his works and ideas, thanks in part to the documentary Il sogno di Lamont Young (The Dream of Lamont Young). The rediscovery of this visionary architect and urban planner aligns with Naples' newfound ability to attract attention to its architectural works. In this regard, could Rione Venezia have been a missed opportunity for the city?