Even according to the cinema, America is no longer a dream? Scorsese's admission of guilt in 'Killers of the Flower Moon'

Joseph Nye, one of the leading American political experts of the 20th century, proposed dividing the exercise of power into two types: hard and soft power. Hard power involves the use of military or economic coercion to achieve foreign policy objectives, while soft power refers to a country's ability to influence the behavior of other countries or its own citizens through non-coercive means, such as culture, values, and ideology. In essence, one of the main objectives is to make oneself attractive. And what is more exemplary of this process than the concept of the "American dream"? American dream, the idealization of the United States as a place where one can start from scratch and achieve one's goals. An image that can be further extended and detached from the concept of social mobility and sees the USA as a promised land where everything desirable is also possible. In this persuasive process, cinema, the quintessential popular art, plays a significant role. Thanks to visual storytelling, films have become the most effective medium for conveying stories, culture, and values to a global audience. Yet, the same cinema that has contributed significantly to the soft power image of the United States has often called into question (as we will see in Killers of the Flower Moon) the American dream.

History of the American Dream

If we can envision the American dream through images in our collective imagination, it is all thanks to cinema, an expressive medium capable of permeating people's lives, through which the United States projected an idealized vision of itself globally. This operation was carried out, in particular, during the Golden Age of Hollywood and the post-World War II era, based on the myth of freedom as a universal value and the possibility of "making it" in society regardless of one's origins. It was during this period, with the beginning of the Cold War, that Hollywood machinery created the American dream, in a narrative in which the capitalist system allowed for upward mobility, in stark contrast to the image of the gray Soviet bloc. It is no coincidence that this was the same era of McCarthyism, where anti-communist paranoia led to the creation of a blacklist of over 300 names: actors, directors, producers, and screenwriters suspected of having sympathies with the Soviet sphere, who were barred from working in the film industry.

The end of American Dream

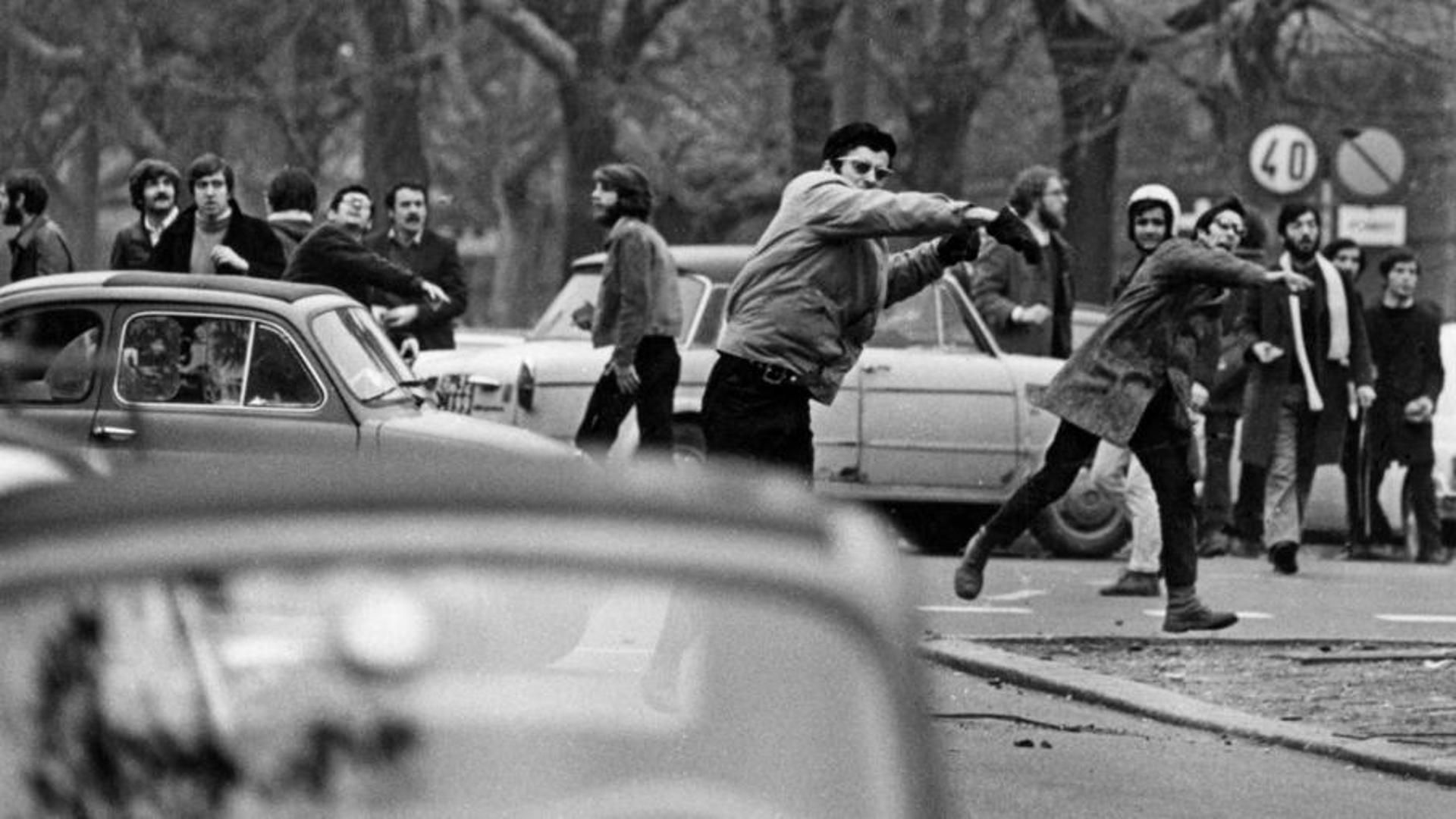

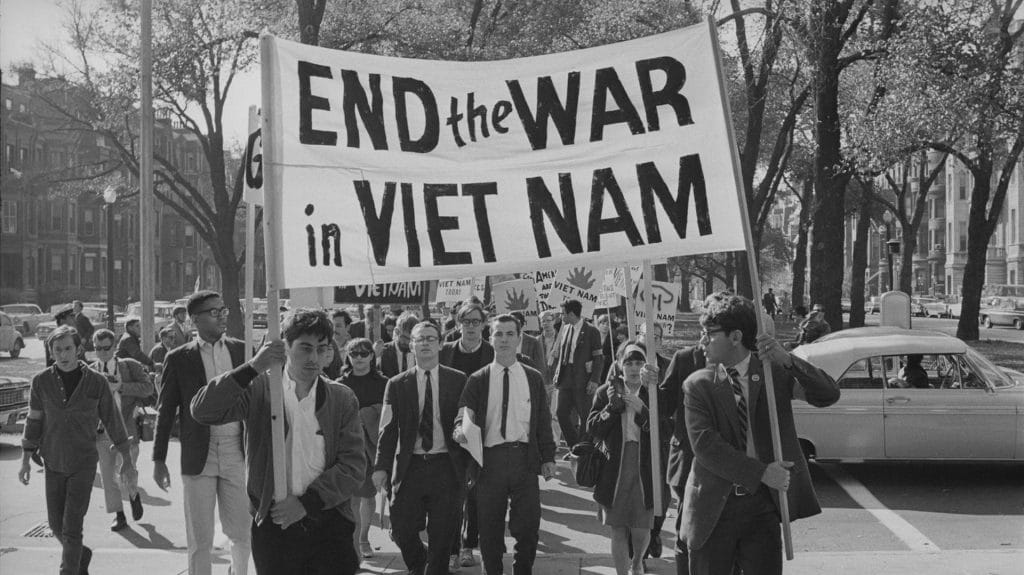

Despite the fact that America is likely to close 2023 as the world's strongest economy, and social mobility still functions better on its soil than elsewhere, we can no longer view it as a promised land. This questioning did not originate with the advent of social media but dates back to the 1960s when the Vietnam War and the assassination of Kennedy marked the death of American innocence, a demise beautifully represented in Clint Eastwood's seldom-mentioned "A Perfect World." Through the story of a fugitive who forms a father-son relationship with a child taken as a hostage, the narrative becomes an exploration of the loss of an entire nation's purity. Wars and discrimination have changed the social order and, consequently, the demands of cinematic storytelling. The transformation of the industry in the 1970s and the rise of New Hollywood led a new generation of auteurs to feel the need to address these feelings in their works. They needed to give America a different face and background. Among them is Martin Scorsese.

Scorsese, the origins of USA, and Killers of the Flower Moon

Martin Scorsese is obsessed with telling the story of America, always with a disenchanted gaze, often harshly, by overturning the pillars created and propagated by Golden Age Hollywood. Consider the heroic individualism, one of the fundamental values of the American dream, disrupted and radically reimagined in Taxi Driver, or the distorted and corrupted idea of upward mobility in The Wolf of Wall Street. However, Scorsese has delved even deeper and more extensively into his idea of the origins of the United States. What are Goodfellas, Casino, or The Irishman if not films about immigrants from around the world who then form the foundation of American society? These are works that question the image of a "universal nation" that we mentioned in the previous paragraphs. In Gangs of New York, Scorsese even imagines the birth of the United States as a violent and brutal gang war. These are all films in which the American dream is dismantled, where the nation is not born from just and shared values but from selfishness and violence. This reflection goes even further with Killers of the Flower Moon, his latest work presented at the Cannes Film Festival and recently released in Italian theaters.

Killers of the Flower Moon: to take responsibility

In the film, a well-known true crime case, a series of murders targeting members of the Osage community, is used to address the broader issue of the genocide of Native Americans. Scorsese once again delves into violence and selfishness as the driving forces of history and as the true parents of the entire nation. The real surprise lies not in the theme but in the approach: a gangster movie avant la lettre but stripped of all the coolness of Goodfellas or Casino. There is no beauty, no playfulness. Instead, there is misery, pathetic desperation, and the banality of human suffering. So much so that Leonardo DiCaprio portrays a character entirely unique in his career, a kind of American incarnation of Hannah Arendt's description of Adolf Eichmann. As if that were not enough, in the ending, we see Martin Scorsese himself take the stage and read the epitaph of Mollie Burkhart (Lily Gladston), the film's protagonist, emphasizing the importance of what is perhaps the deepest and most significant female character ever portrayed by the director and beyond. This represents a significant act of taking responsibility—a creator standing before the world and issuing a solemn and heartfelt mea culpa for the harm done to an annihilated people, to all women, to the new generations, to history, to America, and to a dream that, as beautiful as it may be, has always had its roots soaked in blood.