Why stories about cooking are becoming so anxiety-inducing From "The Bear" to "The Menu," we are in the year of nightmare kitchens

There was an era when movies about cooks and cooking were heartwarming, often romantic and cheerful stories: from Chocolat to Simply Irresistible, from Big Night to Ratatouille via Babette's Feast, Julie & Julia and Soul Food, the world of food and gastronomy was the perfect medium for telling about love affairs, family dynamics, and communities coming together at the dinner table. In later years, the narrative surrounding cooking and chefs expanded beyond romantic comedies and the occasional arthouse film with the enormous spread of television programs such as Masterchef, Hell's Kitchen and 4 Restaurants, which, while creating a myth around chef figures such as Bottura, Cracco, Cannavacciuolo, Borghese, and so on, placed increasing emphasis on cooking as entertainment but neglected the techniques and expertise of the actual culinary art.

Always these programs tended to offer an idealized vision of restaurant work whose façade soon began to erode over the years with the emergence of new kinds of narratives: star chefs retiring from the scene to escape stress, reports of paltry wages and devastating working conditions for kitchen staff, stories of nightmare customers emerging from Tripadvisor comments, and so on. In short, the idealization of the culinary world has been succeeded by a disillusionment that, in recent years, has been portrayed through a mini-stream of films and series depicting the behind-the-scenes of restaurants as something utterly anxiety-inducing. The prime example might be The Bear, HBO's series-hit that plunges viewers into the very agitated kitchen of a small Chicago restaurant; then there is the incredible indie film Boiling Point, shot in a single, anguishing long take and that next year will become a tv series made by BBC; and the upcoming The Menu and Flux Gourmet, in which the kitchen becomes the conduit for dark power plays.

The gradual reframing of the narrative surrounding the world of cooking is actually the result of the disproportionate attention given to it by the media. If today cooking shows themselves are born as self-parodies-think James May: Oh Cook or the ill-fated experiment of Cooking with Paris, for many years the success of Masterchef has created a veritable cultural hegemony that has led to the emergence of the category of star chefs, highly emblazoned chefs who abandon the kitchen to promote potato chips, run TV shows, publish books, open more restaurants than it would be possible to direct, and so on.

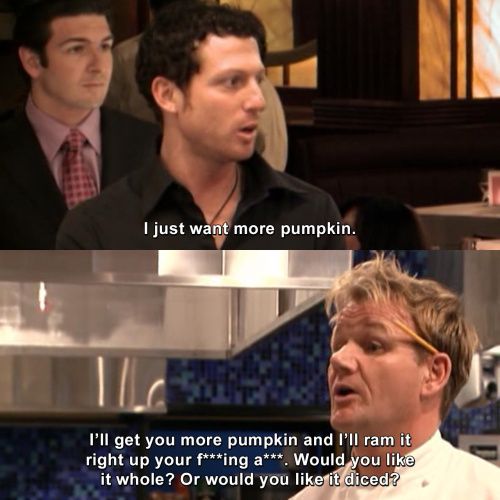

It is precisely this role of absolute fame achieved by some chefs that have created counter-reactions from less spotlighted areas of the restaurant industry: from their colleagues who criticize the transformation of chefs into celebrities, to kitchen workers who denounce terrible working conditions, via customer trolls who create an online ruckus by posting photos of salty receipts or posting reviews that frequently degenerate into online confrontations in which the restaurateur himself intervenes by denouncing the customer's rudeness in turn. Overexposure leads to disillusionment, of course, although in truth the toxicity of restaurant work had not been concealed at all by those programs, which rather turned it into a source of entertainment. Gordon Ramsay built an entire TV persona on verbal abuse-a characteristics copied, in a soft version, by his Italian counterparts who turned it into a kind of icy authority.

This narrative has now gone the proverbial rounds: the authoritarian cruelty that turned the cooks' bad character into entertainment now loses a layer of irony to approach denunciation while remaining entertaining. The early episodes of The Bear strain the issue a great deal, with the protagonist trying hard to implement a hierarchical chain of command in his brother's low-key little restaurant while being haunted by memories of the almost militaristic and utterly traumatizing discipline of his previous role as chef de cuisine in an upscale restaurant - even going so far as to admit to vomiting every morning before entering work because of the tension.

Strangely enough, life imitates art: if enrollment in hospitality schools in Italy (which is where cooking is taught) was 64,296 in 2014, the year of the Masterchef boom after the lockdown «enrollment slightly exceeded 34,000. In practice, in six years, Italians who have chosen hospitality school have almost halved», as Italia a Tavola reports. The same newspaper also quotes Matteo Scibilia, chef at Milan's Piazza della Repubblica and vice president of Confcommercio Vimercate, as saying: «The media effect of television communication has deluded so many young people [...]. The reality is not really like that: to become an accomplished cook you need a lot of experience, a lot of sacrifices, a lot of apprenticeships. [...] So many kids thought that two months of Masterchef could train a great cook».

@hogtiedhannibal Is the most relaxing edit I’ve ever made just Hannibal cooking people? You decide #hannibal #hannibalnbc #hannibaledit #hanniballecter #madsmikkelsen #cooking Satie "Gnossiennes No.1" (piano)(1118396) - Akira Orihata

Clearly, the theme of the staffing crisis go to larger social issues than just media entertainment - but the strand that we might call "hyper-realistic cooking" represented above all by The Bear and Boiling Point is indicative, no less, of a disillusionment with the culinary world that, on this side of the TV and movie screen, established chefs in turn battle by telling their own stories of unpaid internships, weekends spent working, 12-hour shifts in the kitchen, and a series of sacrifices that the younger generation would perhaps consider scarcely acceptable.

Clearly, that the chef-star culture was in crisis was already evident a few years ago, at the height of Masterchef's success, from films like Chef, where Jon Favreau's character rediscovered his passion for cooking by making sandwiches in a van and quitting his stressful job in a French restaurant, or in a series like Hannibal where, with great irony, which emphasized the incredible culinary prowess of the protagonist whose haute cuisine dishes were, however, were made of human flesh. New media, however, having abandoned the comedy and horror undertones, prefer to face reality head-on - as if to say that there's a way out from the toxic mindset of the tyrannical chef. Maybe someone will have found it by the time the second season of The Bear hits our screens.