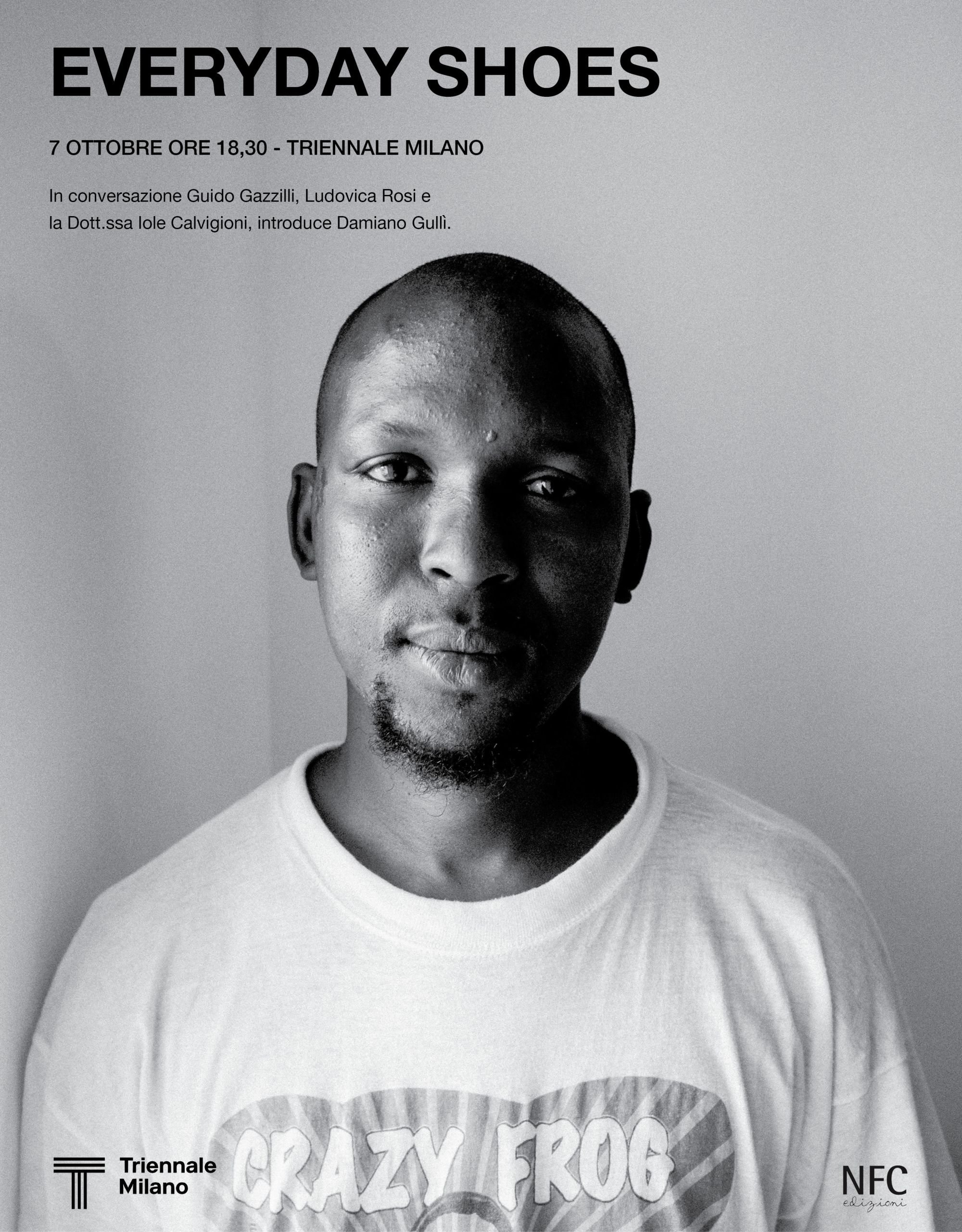

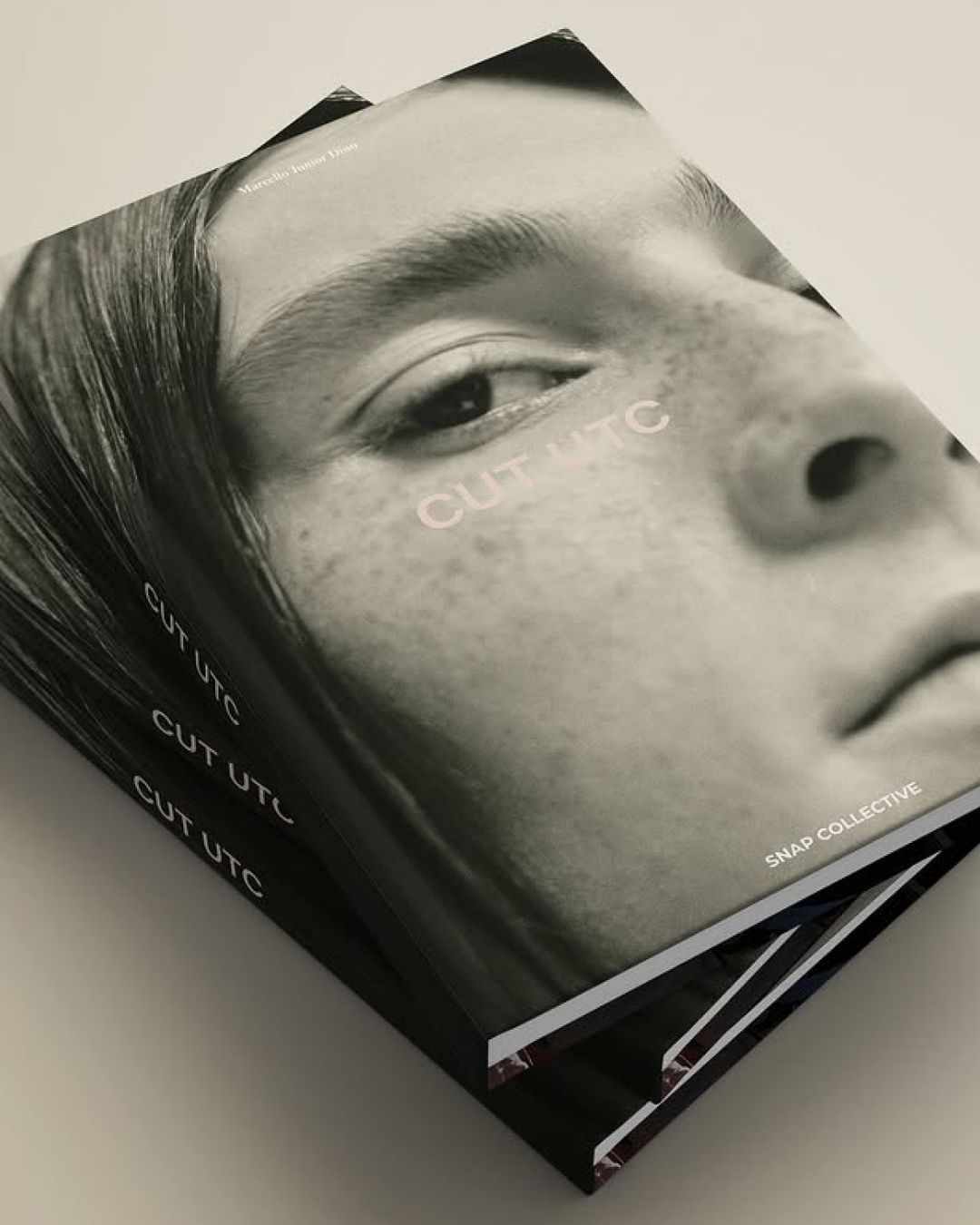

"Everyday Shoes": how to escape from prison through art The new book that uses photography to tell the inner lives of Italian inmates

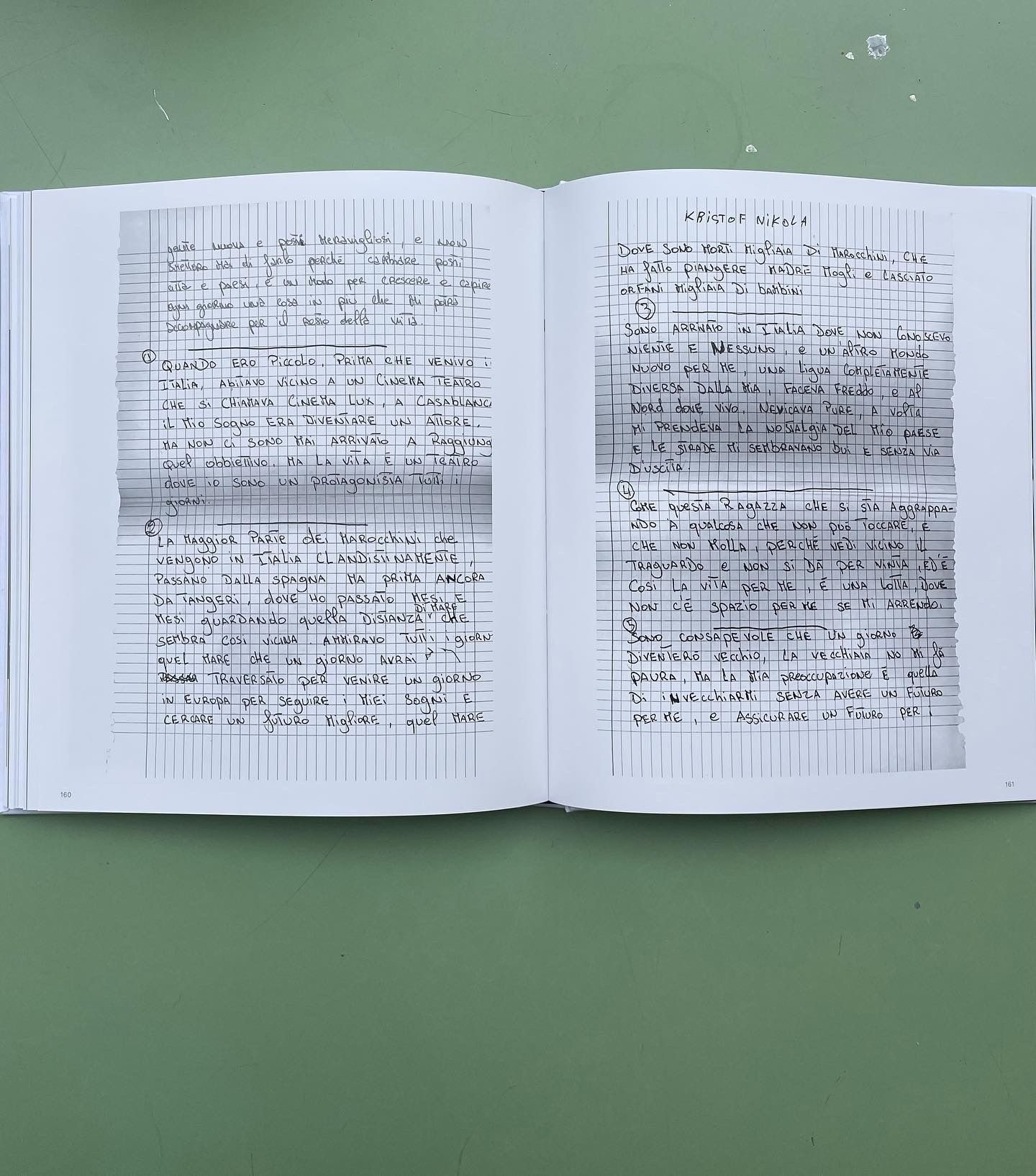

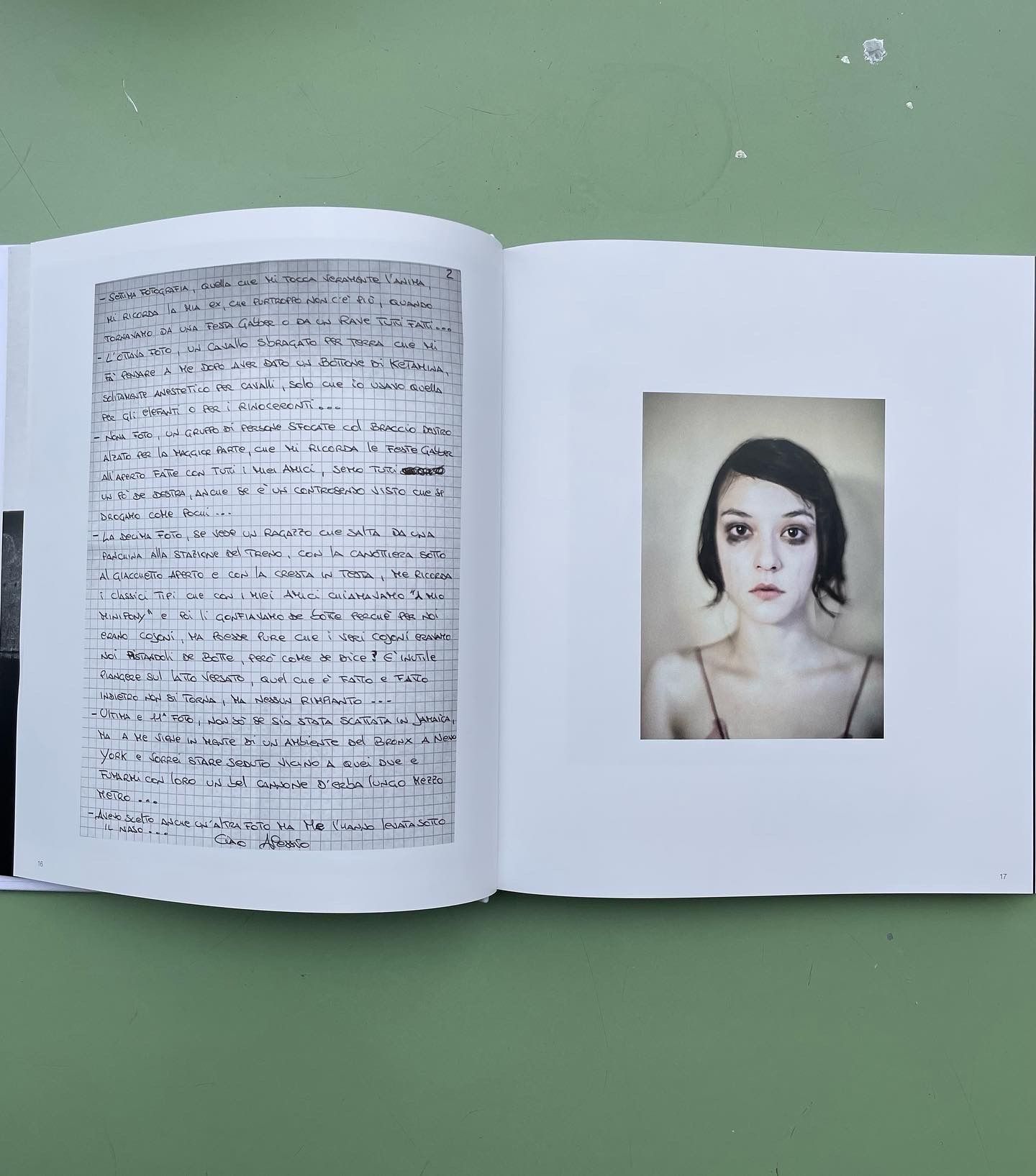

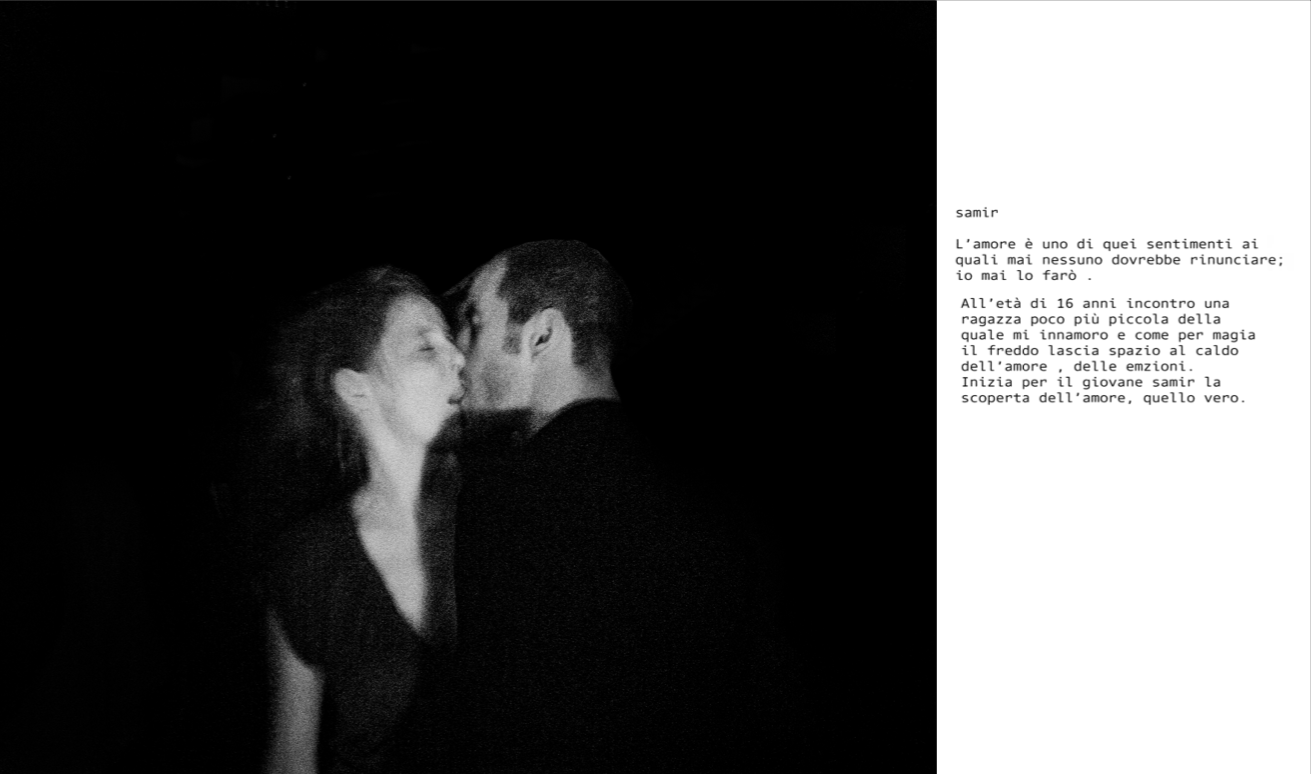

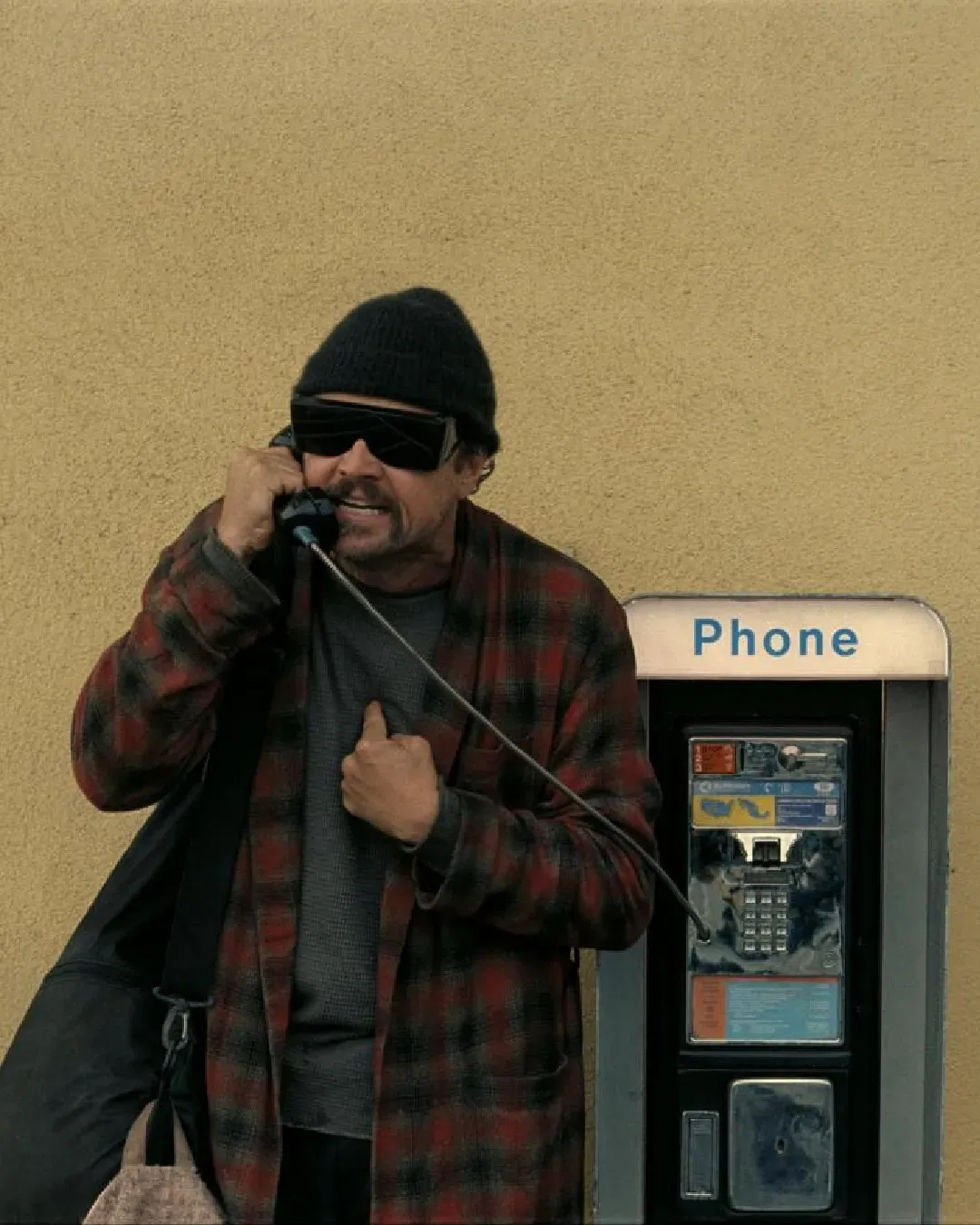

«Hello everyone my name is Alberto, I was proposed to do this path that at first put me a little afraid, I was a little hesitant because I say "mah a picture that me po' give me," I went ahead with this path thanks to the fact that there were no rules imposed on us of any kind, and there was absolute freedom of thought and movement that for us who are in prison is important because we feel and think that someone always wants to read our thoughts, understand what we think. We live by this constant fear of externalizing, and so we always keep everything inside», Alberto, an inmate of Rebibbia, Rome prison, writes. Prisoners, prisons and photography are the three fundamental themes of Everyday Shoes, the book dedicated to Guido Gazzilli and Ludovica Rosi's project, created to open a dialogue, intimate and direct, with inmates of some penitentiary institutions. Thanks to the collaboration of renowned international photographers, a workshop was organized where inmates, through photography and its language, were able to express themselves, in a therapeutic path made of images and words, evoking feelings, memories and hopes. «It was a moment of reflection; it made me think back to the past, my childhood, bad times, marriage, my relationships with women», Alberto continues. The idea was to bring art to places that are often alienating and full of suffering, with the aim of provoking reactions and reflections, while also addressing all the suggestive emotionality that surrounds them.

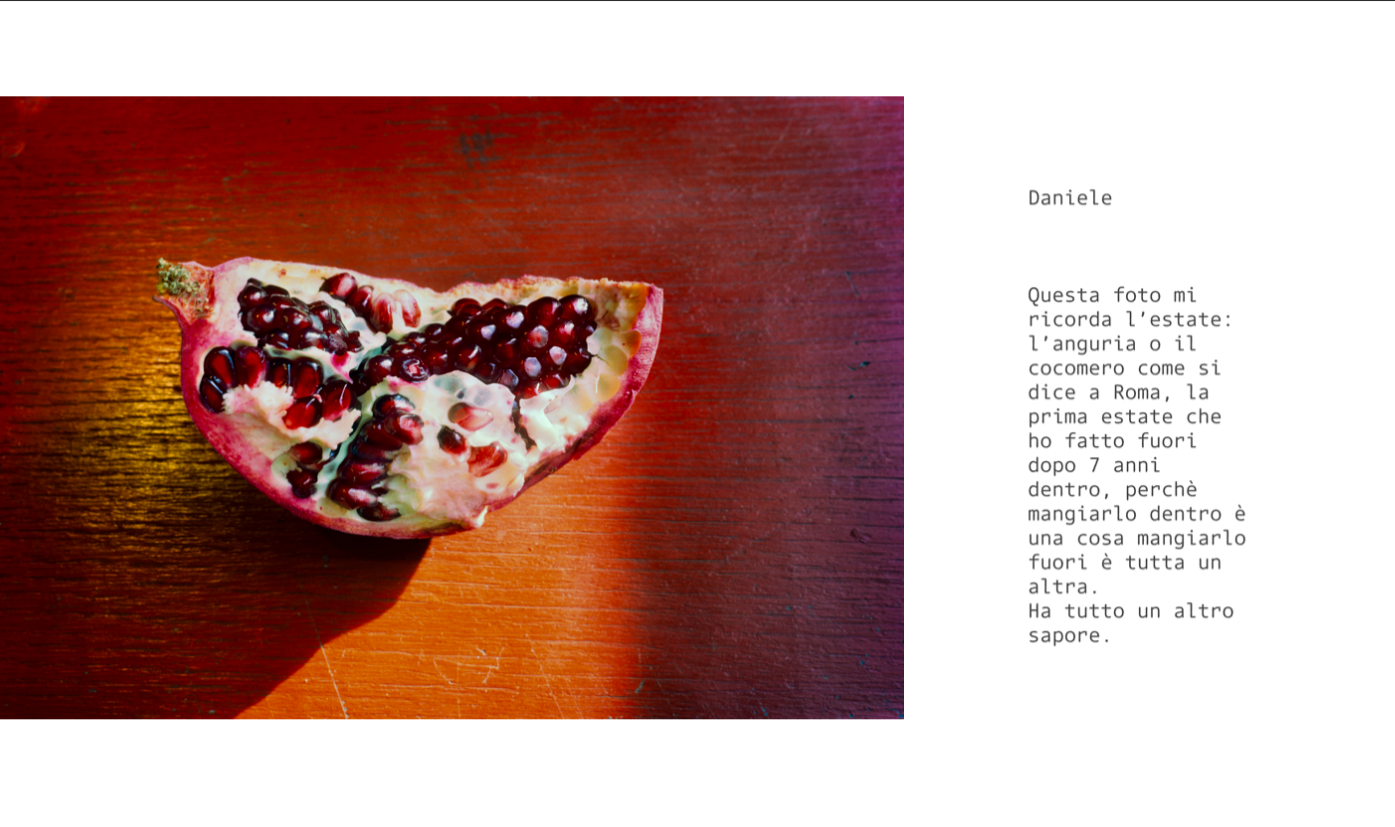

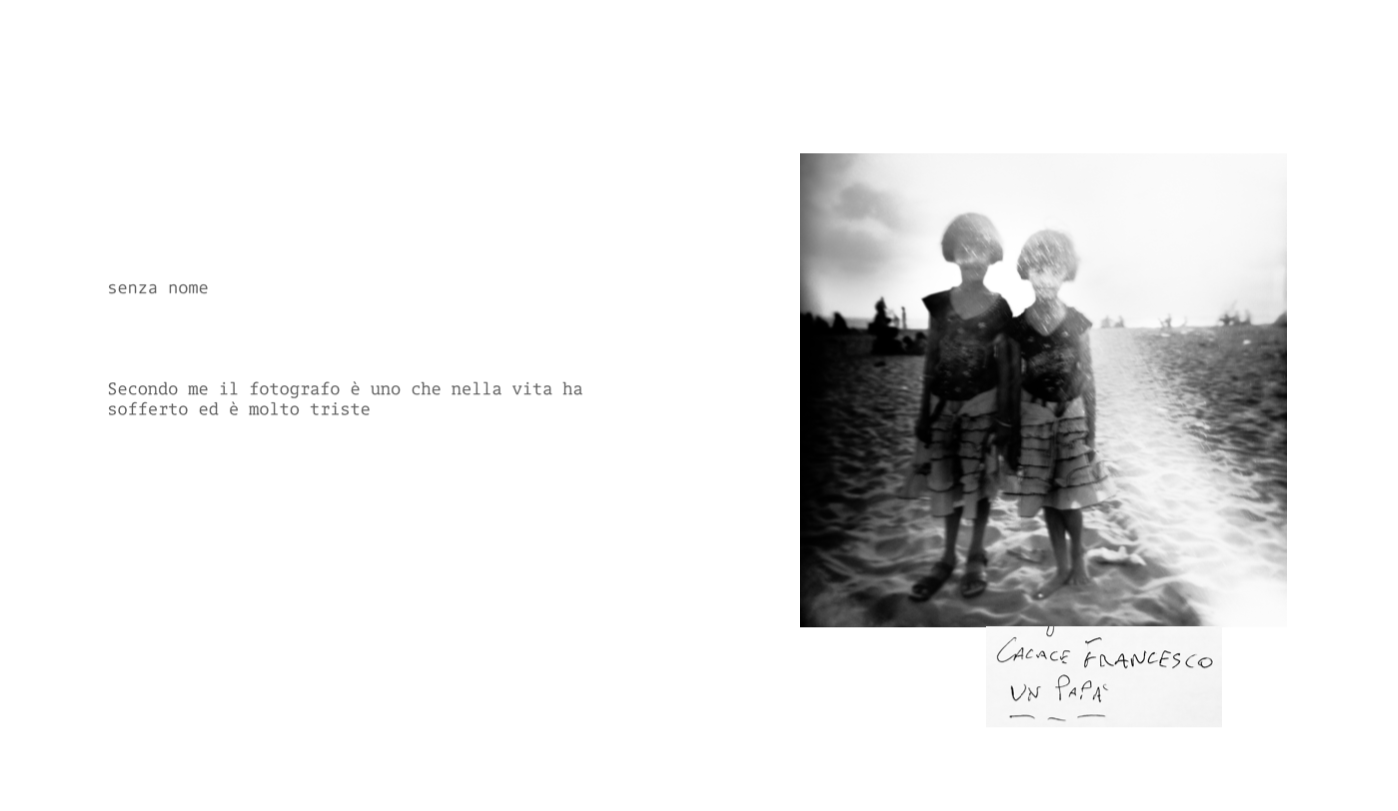

This occasion led the inmates to re-establish a new contact with their emotions and memories, activating a process of (re)discovery of their consciousness and dignity, often stifled during their time in prison, locked in a different world, a timeless non-reality. The book aimed to address all these silences in an honest and unflinching dialogue, opening up to those who live in these often untold places. The title of the book, which at first appears almost incomprehensible, reveals the real condition of the inmates. "Everyday shoes" is reflected in the first image perceived by the photographer, as he first entered the prisons: «I found clean shoes. This is the thing that struck me. The always very clean shoes of the inmates. Over and over I wondered how they were always getting all these new shoes. Who were they getting them from, and why specifically the shoes. Every time I went back inside I would fixate on this detail, impossible to miss and hard to accept. One day during a meeting with the guests of the Rebibbia prison I asked one of them: Why do you have perfect sneakers on your feet? How do you do it? He answered me: Those who are deprived of freedom and are in these places have the shoes that are always white and clean of those who take only a few steps, of those who cannot dirty them with rain, mud and dust, of those who no longer walk outside and are always forced to walk up and down a corridor... ».

This book opens the eyes of those who leaf through it, those who have been protagonists and those who have become part of it in some way. As Piero Calamandrei said: «You have to see them, you have to have been there to realize it. Seeing. This is the essential point».

Prison constitutes a place that no one wants to see, few people talk about it, and it is often very difficult to understand what goes on inside. Feelings are intertwined, but also pain, indifference, marginalization and in many cases we are left with the idea that an inmate no longer deserves to be treated like the rest, but free, human kinds.

In these places there is also a dark side that we are not told about and that Everyday shoes wanted to bring to light: there are those who are sick and are not treated, those who are drug addicts and, in the absence of methadone, use a Bic pen as a syringe. Because in prison the drugs are there, they are just more expensive, but there is a lack of syringes. There are those who stuff themselves with tranquilizers in order to be able to bear it all, there are those in the corner who despair because they have been waiting for months to be tried. Those who stand there because of a miscarriage of justice, serving a sentence for a crime they did not commit, waiting to get their justice.

Even a condemned person has a life, and his or her experience of pain, often lived with very strong physical and psychological consequences, must not be lost, but welcomed and remembered, so that there will be fewer and fewer cases of these identities deprived of dignity.