Past and future of Camden Town The story of the iconic London neighborhood that may now "lose" its Market

For some time now, change has been on the agenda in London, between a new non-European identity and Boris Johnson's 'hasta la vista baby', the news that Camden Market has been put up for sale for around €1.5 billion is about to intimately transform the landscape of the English capital. But how is it possible that an entire 65,000 square meters district, one of the city's cultural institutions, home to the famous Camden Lock Market, Stables Market e Buck Street Market, as well as the cradle of 1970s subcultures, is up for sale? The news has been animating the British press for a few weeks: according to the Financial Times, the owner of the gigantic 16-acre area with buildings housing over a thousand businesses, Israeli billionaire Teddy Sagi, has enlisted the investment bank Rothschild & Co. to identify a possible buyer. It is news that shatters the common imagination of underground Camden, whose nature as a cultural melting pot seemed to elude any market laws, the Camden of brick walls, of the Dingwalls music venue, inspiration for the Clash's debut album, of the bar where Amy Winehouse worked as a teenager, of the historic Cyberdog futurist clothing shop, as well as a meeting place for hippies, punks and skinheads. Yet perhaps the neighborhood we all visited as kids, alone or on study trips, hasn't been the same for a while.

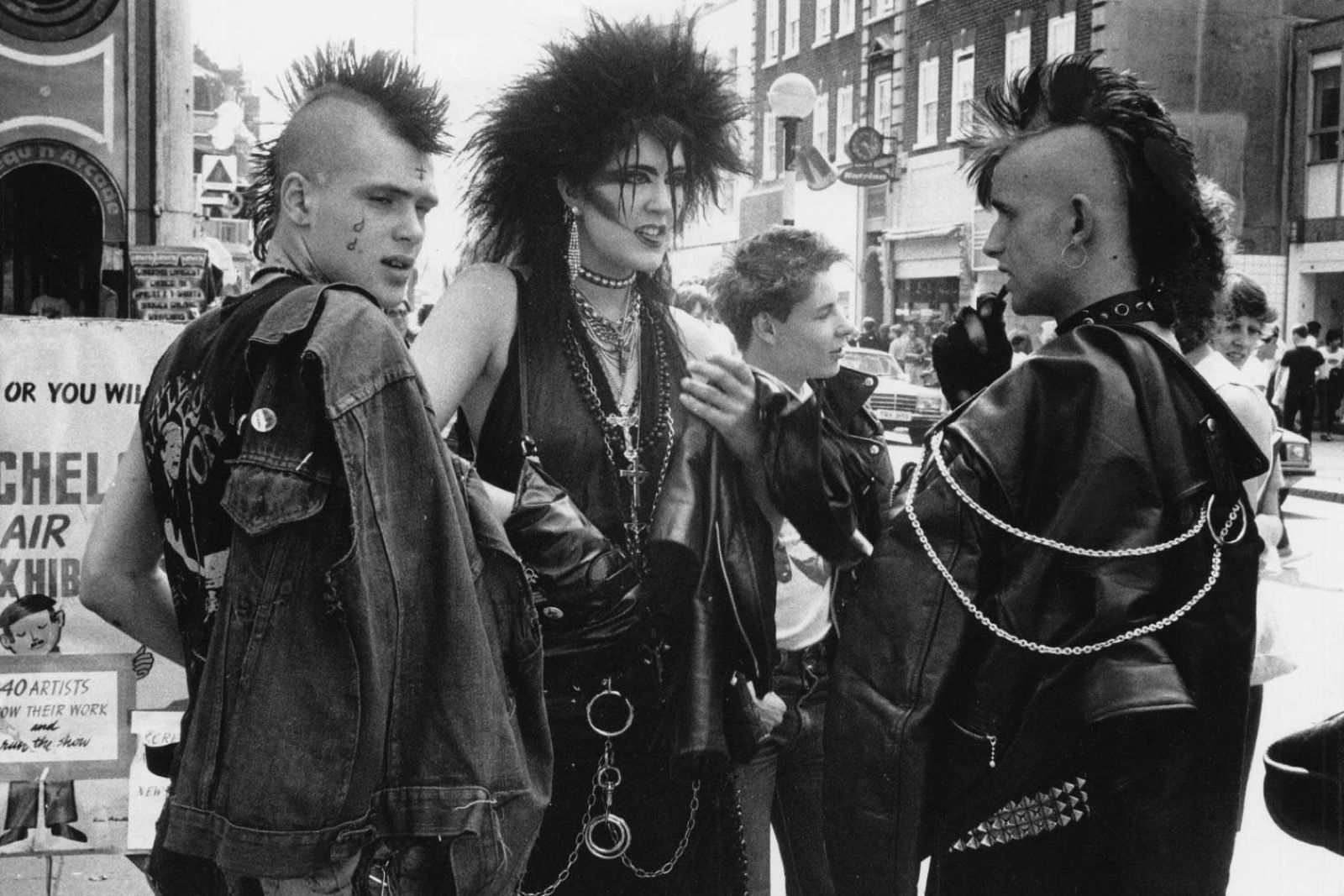

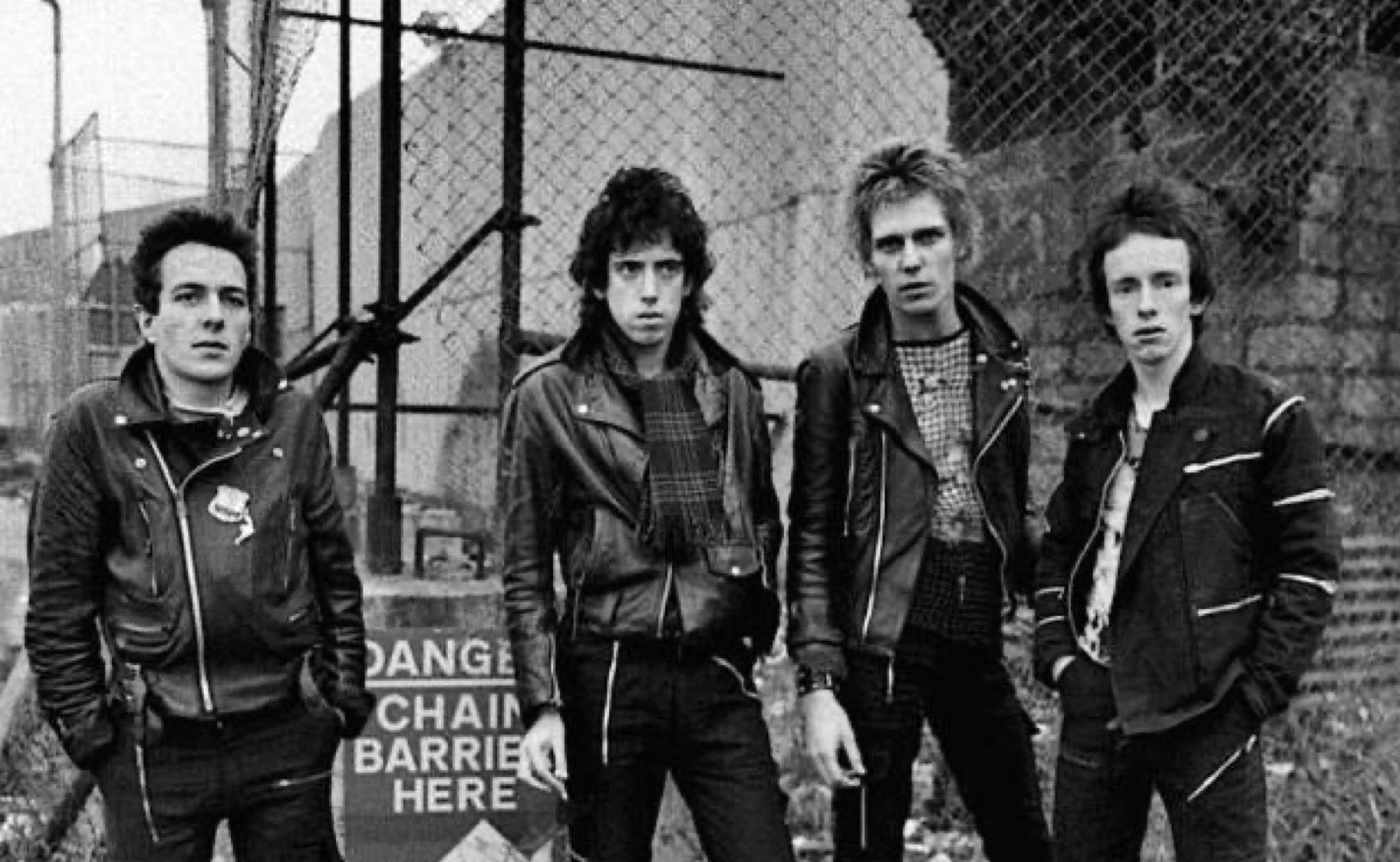

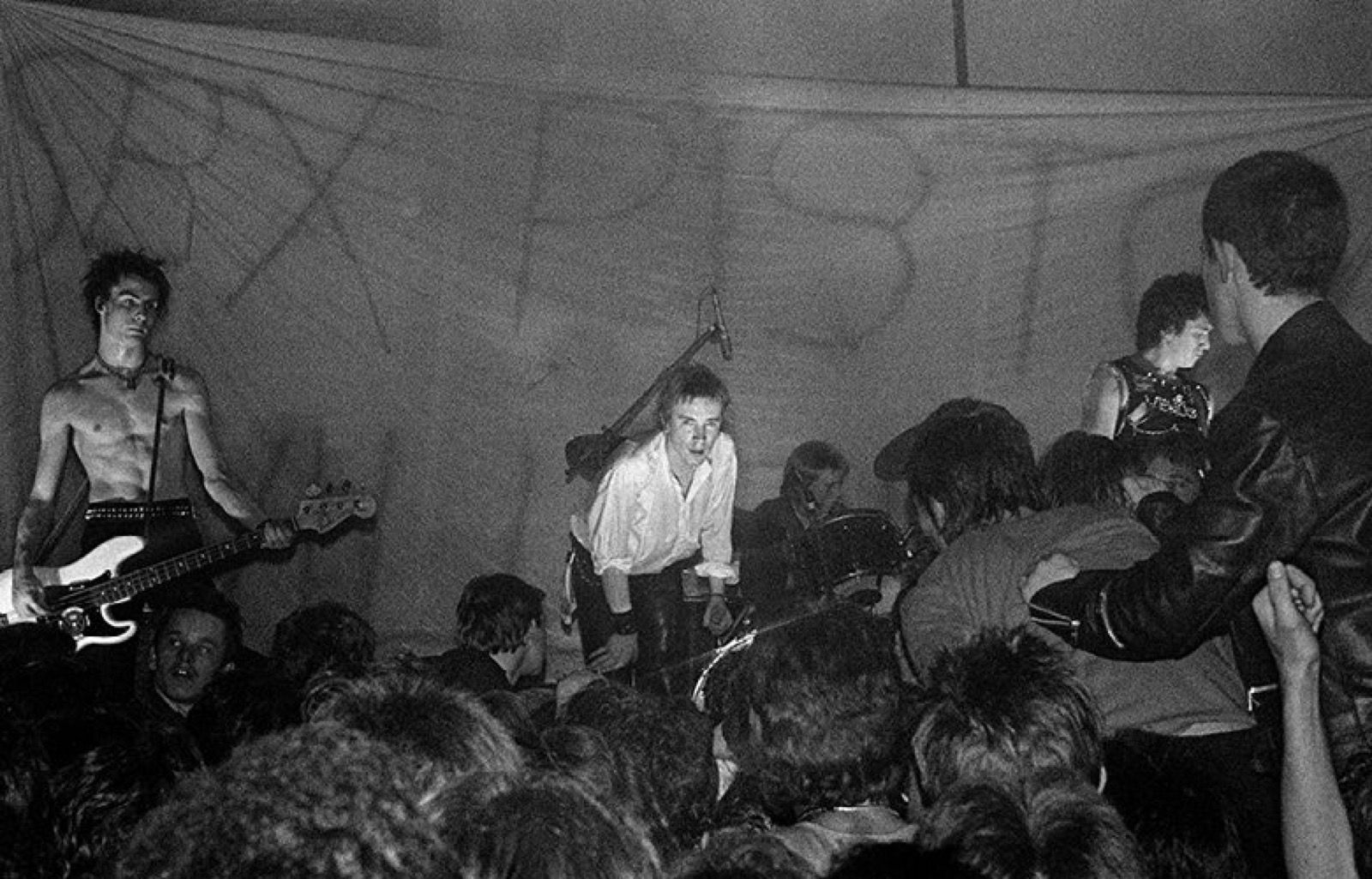

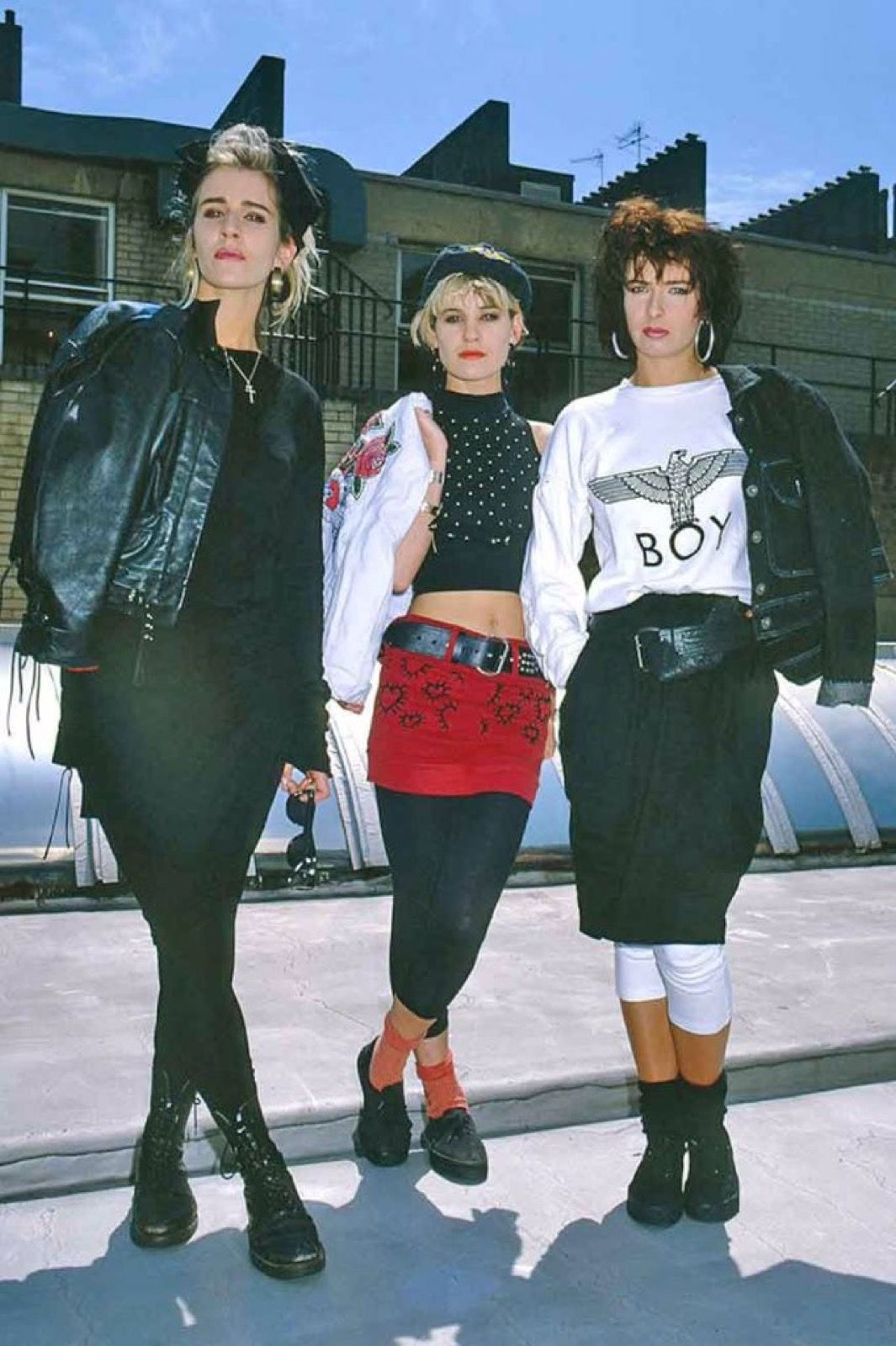

The first Camden Lock market was opened in 1974, and other markets soon followed suit, creating the six-part complex that exists today. In 1966, Pink Floyd debuted at the Roundhouse, a historic neighborhood venue, in London's first late-night raves, however, the origins of punk are disputed and many argue that the movement only began in all its anarchic glory in 1976 (the year Camden Market first opened): on the 4th of July, the Ramones took the stage at the Roundhouse, then played again at Dingwalls the following day, it was just the beginning for the UK's burgeoning punk scene. It is said that artists like Chrissy Hynde - still in the early days of her career - were part of the audience at this historic weekend of rebellion. In the same year, The Clash posed for their eponymous debut album on an old tram ramp in front of their recording space, Rehearsals Rehearsals, which is now part of Camden Stables Market, still a significant tourist attraction for fans of the genre. But why Camden? At the time, the former industrial area of London full of cheap pubs was often described as an 'unsupervised' place where young people felt free to spend their time without their parents or the police getting in their way. It was the perfect place for subcultures to grow and develop, and it was the perfect home for punks.

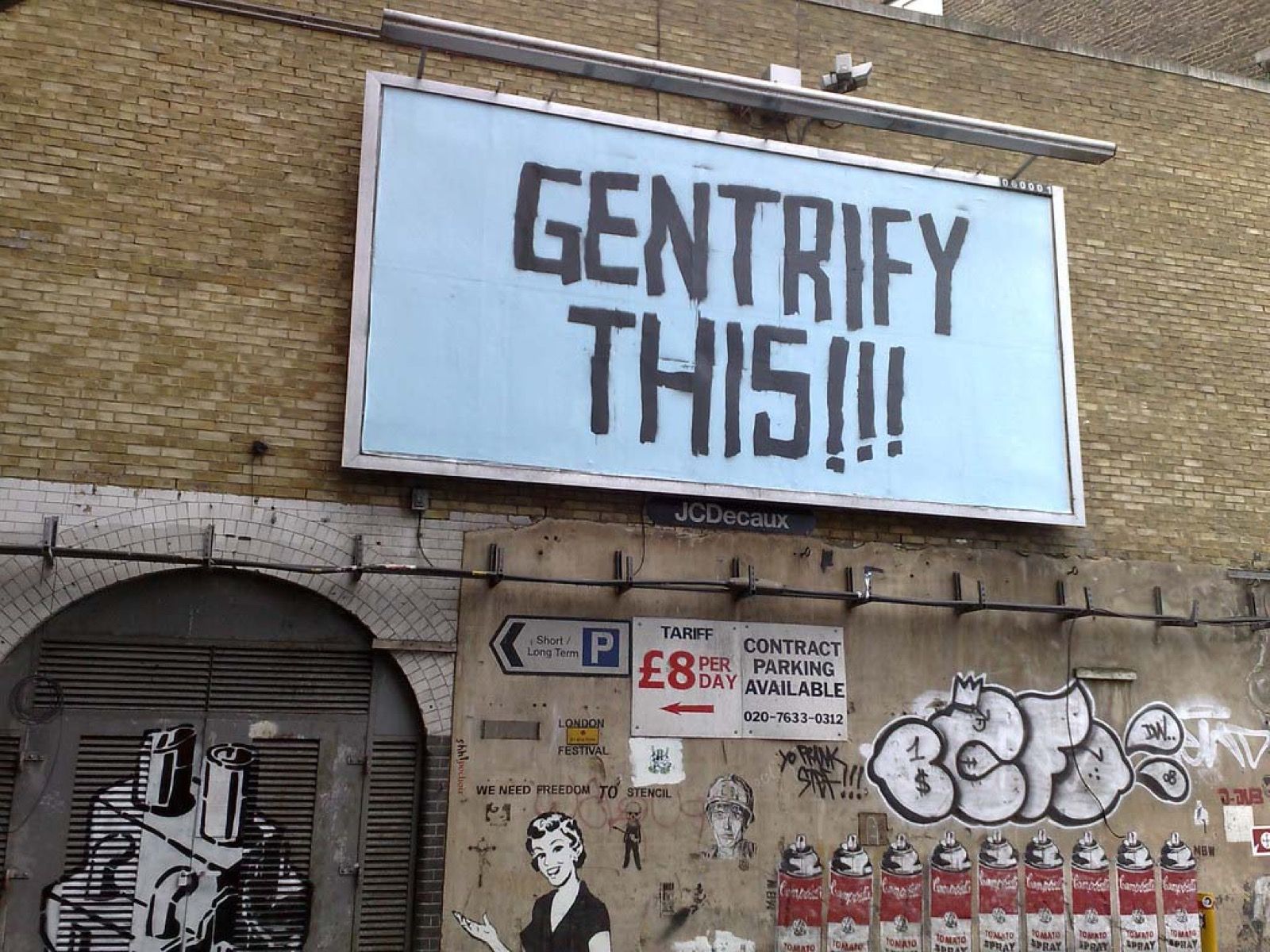

Sagi bought the complex in 2014 and gradually changed its face, demolishing the entire Hawley Wharf area to construct brand new buildings, while small artisans and traders (owners of independent bookshops, tattoo studios, punk and goth clothing shops) closed their doors due to soaring rents. In place of independent shops, brands and chains such as Costa, Caffè Nero, Pret A Manger, Urban Outfitters, and Dr. Martens, as well as new offices of corporate giants, from MTV to Santander, appeared. The same goes for people: despite their role in Camden's history, crust punks are slowly being driven out of the city by law enforcement: "The police are more careful, the rails where we and other locals sit near the Lock have been moved, public places are being strangled", Dave, 19, tells Vice back in 2016. This is called gentrification, the process of transforming a working-class neighborhood into a high-end housing area, resulting in a change in social composition and housing prices, housing speculation that Sagi was planning to monetize as early as 2019 before the pandemic prevented him from doing so.

The sale of the complex would likely push further in this direction, representing the end of Camden Market as a cultural institution. 'Don't sell the soul of Camden Market', headlines the flyer distributed at the entrance to London's largest flea market. On the one hand, the aspiration to breathe the same cultural climate for 50 years is misplaced, as social phenomena are intimately connected to the historical events that motivate them, and hoping for young punks to emulate the Sex Pistols forever sounds rather anachronistic. On the other hand, in this eternal attempt at modernization, at technological and aesthetic refinement, which is driven by economic interests rather than by a true project of environmental redevelopment, metropolises are becoming great glass cases all alike in which people are frantically rushing to get to work without there being any difference between New York, Paris or Milan. Cleaner and safer, for sure, but soulless.