Il valore ideologico di un abito «Perché vesto sempre di nero», intervista a Michelangelo Pistoletto

Il valore ideologico di un abito «Perché vesto sempre di nero», intervista a Michelangelo Pistoletto

But I am not against colors. Look, let me show you my socks (he laughs, lifting his trouser leg to reveal yellow polka dots on a red background). I don’t reject color; in fact, I think that black itself serves as the foundation for a colorful universe. But take, for example, the robes of monks from any religion—their black robes are non-consumerist, and so is mine.

Il valore ideologico di un abito «Perché vesto sempre di nero», intervista a Michelangelo Pistoletto

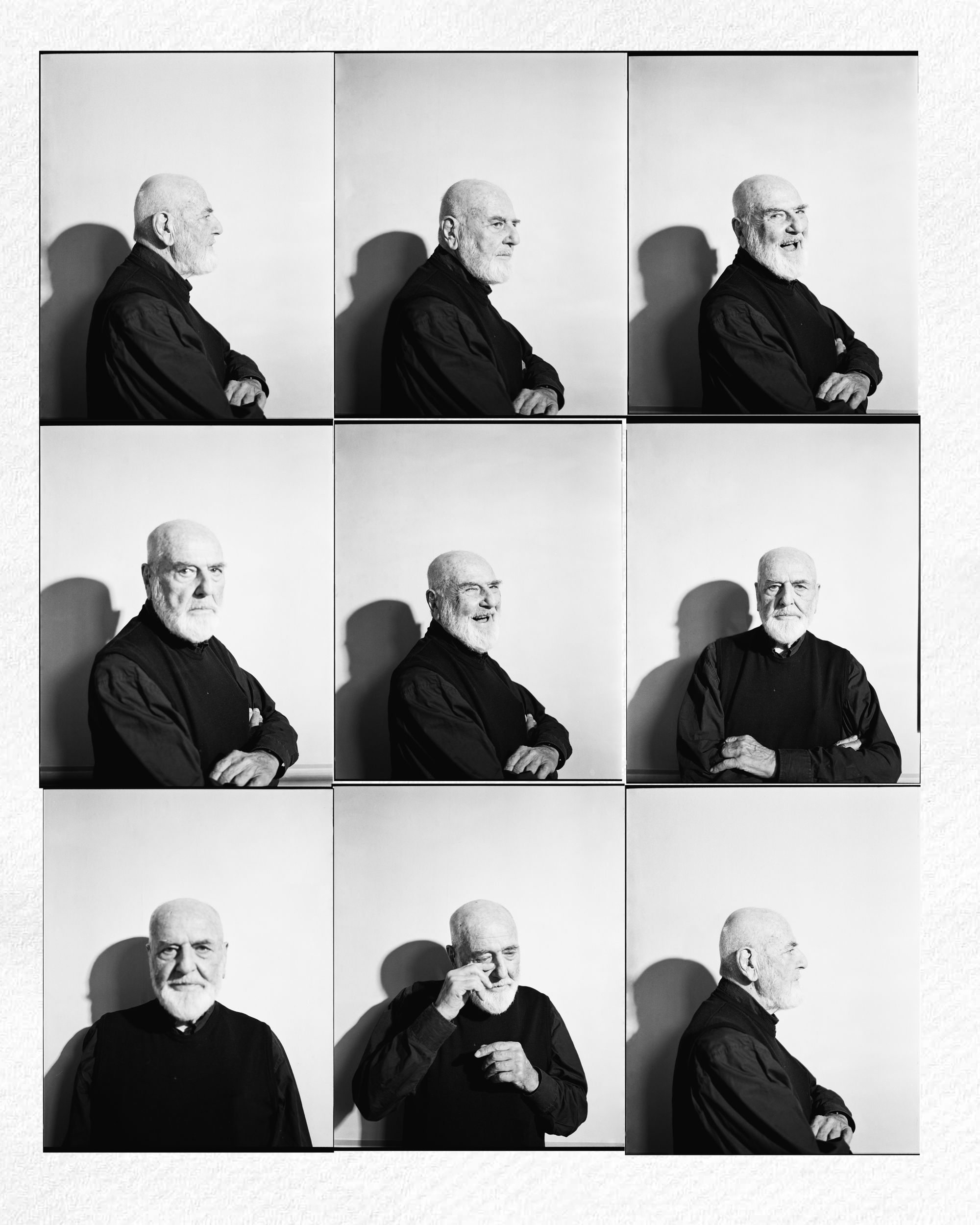

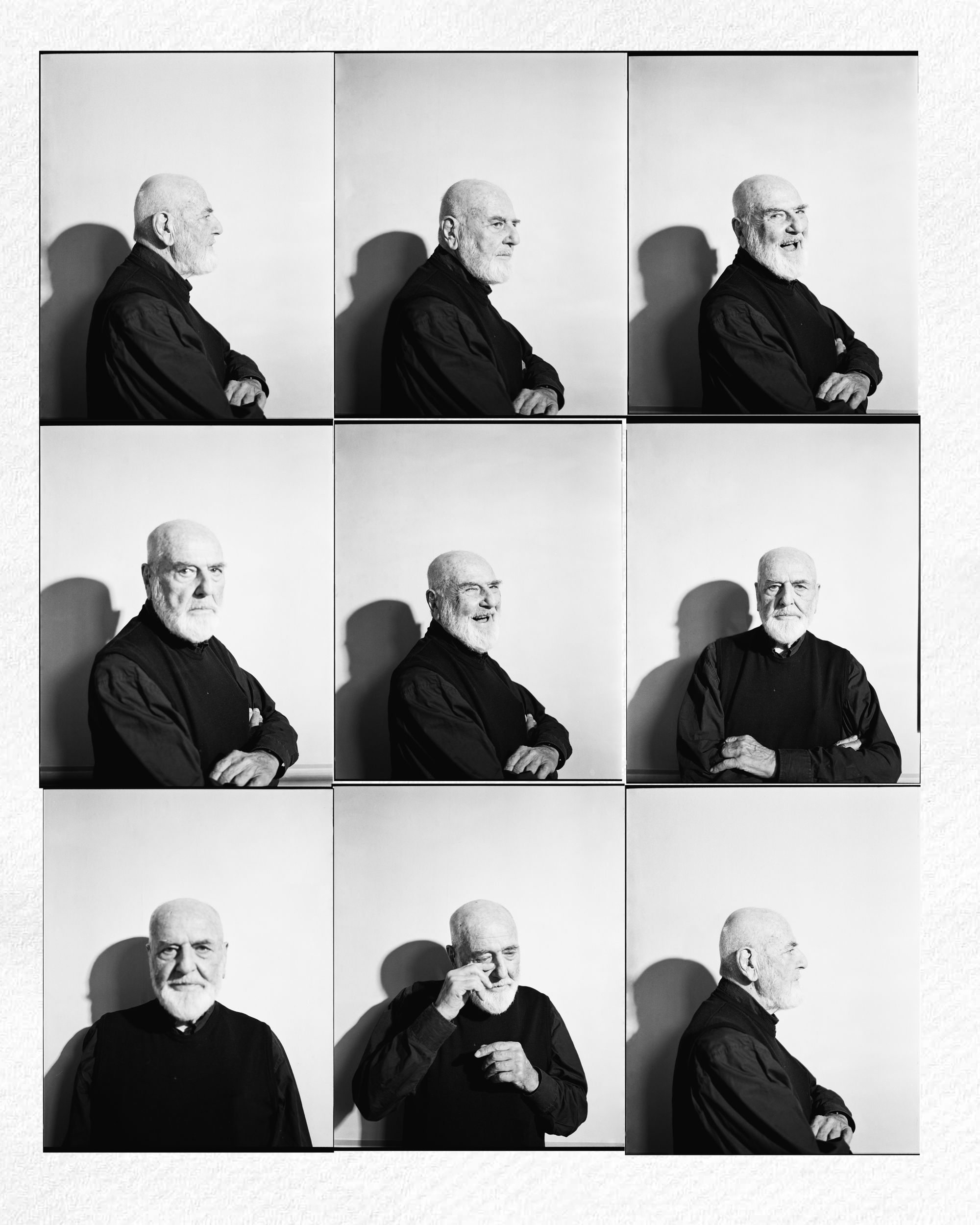

There is this book by Alain Elkann titled La voce di Pistoletto, in which the cover and the back are filled with portraits of my face, each one different from the other. I have always taken on different forms until, in 1969, I created a work called L'uomo nero (The Black Man). The Black Man, like a mirror, has no image of its own. Black is not only on one side or the other; it is everywhere. It represents the void within which the stars exist.

Il valore ideologico di un abito «Perché vesto sempre di nero», intervista a Michelangelo Pistoletto

Il valore ideologico di un abito «Perché vesto sempre di nero», intervista a Michelangelo Pistoletto

But I am not against colors. Look, let me show you my socks (he laughs, lifting his trouser leg to reveal yellow polka dots on a red background). I don’t reject color; in fact, I think that black itself serves as the foundation for a colorful universe. But take, for example, the robes of monks from any religion—their black robes are non-consumerist, and so is mine.

Il valore ideologico di un abito «Perché vesto sempre di nero», intervista a Michelangelo Pistoletto

There is this book by Alain Elkann titled La voce di Pistoletto, in which the cover and the back are filled with portraits of my face, each one different from the other. I have always taken on different forms until, in 1969, I created a work called L'uomo nero (The Black Man). The Black Man, like a mirror, has no image of its own. Black is not only on one side or the other; it is everywhere. It represents the void within which the stars exist.

Il valore ideologico di un abito «Perché vesto sempre di nero», intervista a Michelangelo Pistoletto

A ceramic Dalmatian sits in front of an imposing mirror with a gilded frame; a small table is covered with trinkets, colorful candles, and pens; a wooden desk is strewn with pencil notes; and yet another mirror, this one with a painted noose above it. If we were to define a house by the objects it contains, the apartment of Michelangelo Pistoletto, located within the broader complex of Città dell’Arte in Biella, would speak of playfulness, irony, and a distinct inclination towards color. But to associate the house with its owner might produce an off-putting effect. Pistoletto is solemn and composed. He makes space for us among his notes, offering a steaming moka pot and a firm handshake. His clothing - except for his socks, which we later discover to be red with yellow polka dots - is all black, from the wool sweater to his tailored pants. His iconic hat and scarf, which have characterized his public image for years, are in the other room. As he sits at the table and sips his coffee, the noose drawn on the mirror behind him appears to encircle his neck in a vaguely unsettling optical illusion, looming in and out of view throughout the interview, depending on his posture. We learn from Pistoletto’s words that the mirror alters our perception of reality.

Indeed, we spoke about death, as well as sustainability, humanity, the ideological value of clothing, and the significance of his attire. The author of Venere degli Stracci (Venus of the rags), the man whom Germano Celant saw as the perfect representative of Arte Povera, as well as the tireless environmentalist who founded Città dell’Arte to prove that a better and different social model can exist, talked about his involvement with the Sustainability Awards by Camera Moda and why he only dresses in black. In doing so, he revealed the mystery behind the aesthetic paradox between the extravagance of his home and the sobriety of his clothing: «I am not against colors. Here, let me show you my socks (laughs),» Pistoletto admits, lifting the leg of his trousers to reveal yellow polka dots on a red background.

You describe yourself as “a scientist who speaks through images.”

Yes, I am a scientist who speaks through images. I’ve said this before, and I confirm it because my artistic work is not just an imaginative, emotional, or fanciful expression but a quest for knowledge. It’s precisely because I want to understand that I put my emotions at the service of a rational inquiry. There’s a logic that led me to find, through the mirror paintings, the phenomenological dimension of existence. When I speak of phenomenology, I mean that I don’t place my own proposals in the paintings as definitive, autonomous, and absolute, but rather, I ask reality, through the mirror, to give me every possible image of what exists. From this image, I try to understand what phenomenology allows existence to exist. This research connects me to science. When I make an artistic discovery, I experience the greatest excitement because I achieve a kind of knowledge that didn’t exist before. You move from a lack of something to a new creation, a thing that now exists.

The Venere degli Stracci and the Terzo Paradiso have, since 2012, become symbols of the Sustainability Awards by Camera Moda. I wanted to ask about this choice, which furthers the complex discussion on the relationship between art and fashion.

Fashion is one of the important aspects of our social life because clothes are like our second skin. The garments we wear express social and political ideas that spread throughout the world. In ancient times, there were always distinct costumes: each country had its own attire with peculiar embroidery, cuts, and designs. Everything, from headgear to trousers, indicated belonging to a specific place. In modernity, absolute freedom has been discovered - a fantasy expressed to the extremes in fashion, leading to extraordinary modern liberty. But we must always consider the material, the very concept of consumption.

And how do we deal with the concept of consumption?

By focusing on the superfluous rather than the necessary. Many factors contribute to the situation we face today: a flood of rags that fill vast areas of land. In Africa, for example, beaches are covered in meters and meters of discarded fabrics made without any necessity, fueling a consumerism that overwhelms us. Consumerism is a mental, cultural, and economic phenomenon, and if it were only that, it would be fine, but it also invades us physically, and materially. If I were to recreate the Venere today it would probably be made of plastic to represent the quantity of waste flooding our oceans. The Venere doesn’t offer a solution but sends a message.

Does your choice to wear only black also convey a message?

There’s this book by Alain Elkann titled La Voce di Pistoletto (The Voice of Pistoletto), where the cover and back are filled with portraits of my face, each one different from the other. I’ve always taken on various forms until 1969 when I created an artwork called L’uomo nero. The piece represents the game of l’uomo nero (musical chairs), with 21 chairs and 21 people seated; everyone stands up and tries to find a new seat, but there’s always one person left standing. That’s L’uomo nero, and it corresponds to the mirror. After all, the mirror represents everything that exists, except itself, because a mirror has no image of its own. L’uomo nero has no image of his own and is like the blackness we see at night when looking at a starry sky. Black is not just on one side or the other - it’s everywhere. It represents the void within which the stars exist. The universe unfolds within this great void. So, the blackness of this game also becomes the blackness of the mirror, of space, and of universal time. But I’m not against colors. Here, let me show you my socks (laughs, lifting the pant leg to reveal yellow polka dots on a red background). I don’t reject color; on the contrary, I think black serves as the foundation for a colorful universe. But take, for example, the garments worn by monks of any religion—their black clothing is anti-consumerist, and so is mine.

Let me ask a question that’s a bit off-topic from what we’ve discussed so far. When speaking about death, in a prior interview, you said: “We are all already immortal.”

We are all immortal because we carry within us the immortality of those who came before us. Nothing new exists in the physical nature of things. This immortality isn’t, let’s say, fully understood, emphasized, or consciously lived because animals live through an immortality that is simply part of the universe. Human beings have found a way to leave traces, through signs, words, images, sculptures, shapes, and numbers. And these traces we have left, the ones left in the past, are always present in future generations. We have reached a point today, through museums, literature, and even artificial intelligence, where all memories are brought together. If you’ve left a mark, you are present in the way that this mark combines with all other marks in the future. That’s immortality.

Intervista di Maria Stanchieri, foto Vincenzo Schioppa.