Can luxury make money while degrowing? The real problem of fashion is an economic issue

Luxury is no longer sustainable. And it is not just an environmental sustainability issue: the severe sales crisis is proof of how the economic model applied to the supply chain at this moment is causing more harm than good. As in all profit-driven industries, fashion and luxury also base their modus operandi on the micro and macroeconomic concept of economies of scale: the more production increases, the lower the costs and the higher the profits. This could work—if everything that is produced were sold—but we know that is not the case. Not only are major luxury groups sitting on billions worth of unsold merchandise, the storage and disposal of which come at astronomical costs, but the offloading of this inventory through off-price channels has become an accounting line for many brands. This mass of unsold goods exacerbates the issue of sales now reaching historic lows, especially as the Chinese spending power that once drove up sales volumes has now slowed. Many unsold products are then pushed into gray markets (as we saw last year with the proliferation of sample sales), but over the past year, even these have been suffocated by excessively high prices—while all others are simply destined for landfills. The issue is that by following the philosophy of economies of scale and, to put it simply, mass production, most luxury brands continue to produce an excessive amount of merchandise, chasing the capitalist ghost of infinite growth, which must materialize every quarter. But the real problem is this: how can the industry continue to grow, producing more and more, while expecting theoretically ever-higher margins in an economy with ultimately finite resources? According to various theories proposed in recent years—but which nss magazine is now trying to shape into a concrete framework for the general public—fashion should slow down its race for growth. Beyond being an outdated economic model, this race also represents a deeply ingrained mindset among top managers. And now that the sales crisis has exposed the fragility of an already bloated system, it may be time to look at the system from the bottom up.

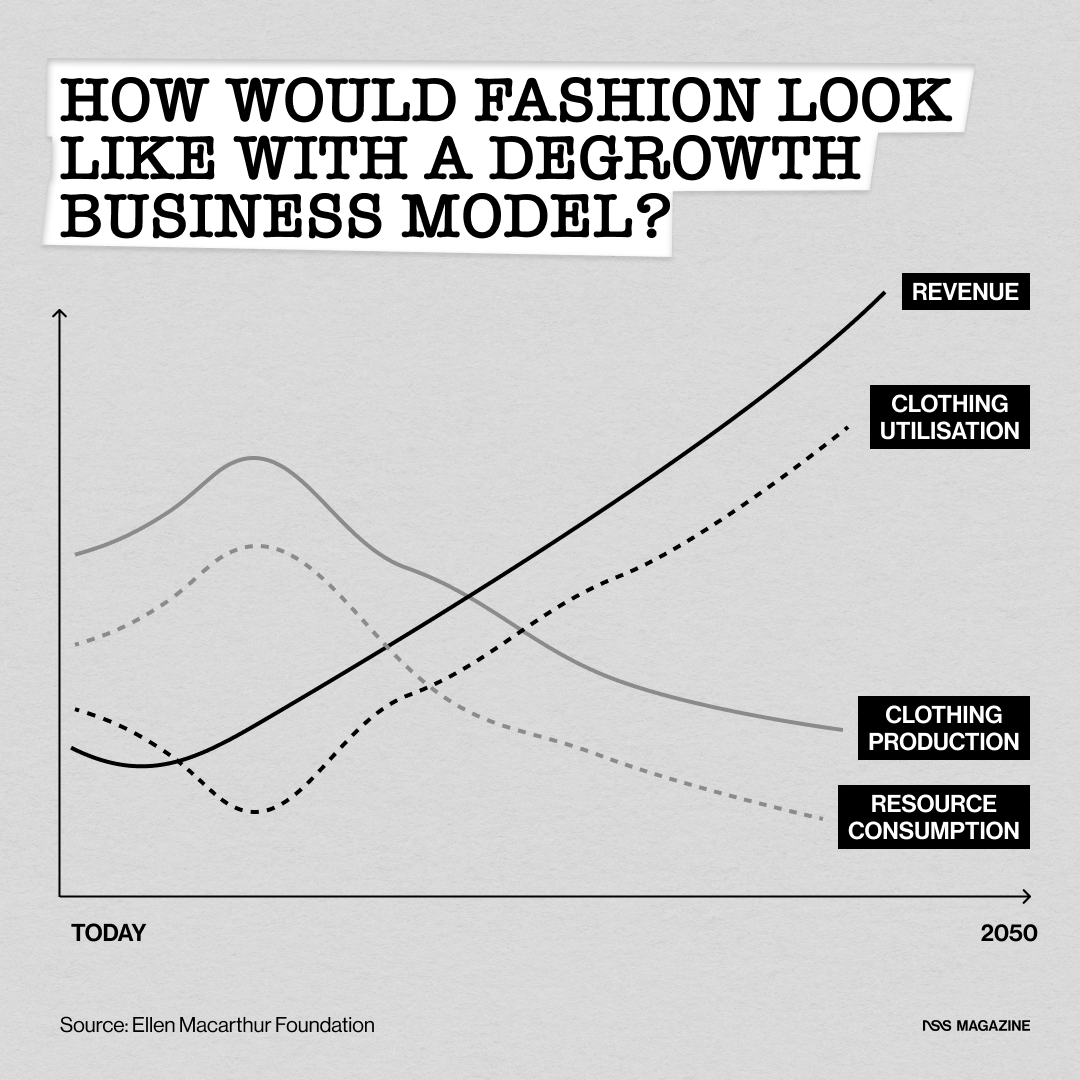

The concept of “degrowth” refers to a critique of capitalist growth that emphasizes the organization of the economy around human needs rather than capital interests, advocating for anti-accumulation and de-commodification as tools to address issues of overproduction and colonial appropriation. In the fashion industry, the application of this economic model becomes less radical and more focused on production volumes. As explained in Textile Exchange's report Reimagining Growth Landscape Analysis, which refers to national economies, the degrowth theory suggests that controlled reductions in production and consumption will be essential not only from an environmental perspective but also from a social one. This does not mean immediately reducing volumes or compromising national GDPs but rather slowing down and containing the flow of material and energy resources within planetary boundaries while ensuring minimum social standards. A crucial aspect of the theory is that this reduction should not be applied indiscriminately or universally: the primary focus is on high-income countries, such as those in the West, which have historically contributed the most to excessive resource consumption. On the other hand, developing economies still have room to grow to meet the fundamental needs of their populations. Essentially, the degrowth theory promotes slow but “happy” growth, distancing itself from the purely numerical and mathematical conception of growth that is fundamental in a capitalist system—one that, in one way or another, ultimately negatively impacts both the planet and the supply chain.

@chloe.longname Im guilty too tho ngl

original sound - chloe.longname

Applying this concept to the fashion and luxury industry, it becomes evident that the issue of overproduction is not just an environmental risk but also an economic boomerang that is already showing its negative effects. The latest industry data confirms the urgency of change: currently, the fashion industry is set to increase its emissions by 2.7% annually, with growth that, if maintained, will double the maximum emissions allowed to stay within the 1.5°C limit established by the Paris Agreement by 2030. The alarming picture outlined by McKinsey & Company and Global Fashion Agenda highlights how the environmental impact of fashion is still far from being under control, despite some sectoral progress. Even estimates from the Apparel Impact Institute, while slightly more optimistic, project a 40% increase in emissions by 2030 compared to 2022 levels. Reducing production volumes while maintaining exclusivity, promoting circular models, and investing in sustainable materials thus represents one of the few viable strategies for an industry that, despite being inherently linked to the concept of desirability and rarity, has so far followed production logic akin to those of fast fashion. After all, the only brands that have emerged unscathed from the luxury crisis are those in the ultra-luxury segment, which have been applying a semi-degrowth strategy for years. The simple fact that Hermès does not offer every customer the possibility of purchasing a Birkin or a Kelly means that the production of these bags is significantly lower than that of a Gucci Jackie or a Prada Galleria, which undergo seasonal variations based on the creative themes of each collection. In this way, Hermès maintains a lower production rate compared to its competitors while simultaneously increasing the brand’s desirability year after year.

Fast fashion is the reason it’s impossible to find quality clothes for accessible prices because they’ve pushed the standards down for mass market brands in favor of speed. They cater to those who can afford to shop weekly, not people who need long lasting, accessible clothing.

— Lakyn Thee Stylist (@OgLakyn) February 21, 2024

Overproduction, the massive use of fossil-based textiles, and ineffective waste management highlight the urgent need for a radical shift toward reducing resource consumption and waste to stay within planetary boundaries. The goals set by both governments and industry players demand a drastic reversal: reducing the sector’s overall footprint by 50% by 2030, in line with the Paris Agreement and the IPCC's recommendations, which call for a 45% reduction in global emissions compared to 2010 levels by the same year, ultimately reaching carbon neutrality by 2050. However, current projections paint a completely different picture: according to the Global Fashion Agenda, the industry's production volume could increase by 80% by the end of the decade, rising from the current 100 billion garments produced annually to approximately 180 billion, effectively nullifying any sustainability efforts. Walter D’Aprile, co-founder and editor-in-chief of nss magazine, emphasized in his interview with The Stanza Media that the issue of overproduction must be tackled through a radical paradigm shift. «We must stop overproduction. Maybe I’m a dreamer, but I would like to change the business model because right now, we are obsessed with how many pieces we sell. So we keep producing more and more of the same item, whereas we should be thinking about how to sell the same item multiple times.» The problem with luxury fashion is not only excessive production but also the fact that the system is still entirely built on the logic of quantitative growth, ignoring the potential of a more circular and long-lasting economy. It is now necessary to shift the focus from the number of items sold to the possibility of selling the same item multiple times, transforming the business model from a linear consumption economy to a more dynamic and relational system. Brands must sell relationships, not just products, through content creation.

It is now evident that there is a total discrepancy between declared objectives and production realities, reflecting a systemic inability to implement radical changes. A striking example is James Reeves' comment in response to Kohei Saito’s argument on the need for systemic change to effectively address climate change and global inequalities: «It will be quite a shocking idea for many business people». This statement aligns with PwC’s 2024 survey, which found that nearly half of CEOs worldwide believe they will need to reinvent their businesses to remain competitive over the next decade. However, this need for reinvention still appears confined within traditional business logics, focusing more on modifying existing business models rather than implementing a true structural shift in the system. This is precisely where degrowth could offer a tangible alternative: not merely a reduction in costs or a marginal adjustment, but a complete redefinition of priorities and strategies, placing sustainability and long-term economic resilience at the center. This was the main reason why 2024 was an extremely chaotic year for the luxury industry: the continuous turnover of creative directors was merely a symptom of a much deeper and more structural issue. Over the past 12 months, the vast majority of major groups have altered and overturned their investment strategies. Take Tapestry, for example, which not only abandoned its acquisition of Capri Holdings in recent months but, according to Vogue Business, has recently decided to sell Stuart Weitzman for $105 million. Similarly, at the beginning of 2025, Kering opted to sell all of its outlet stores to reduce debt—an investment that, however, as reported by Business of Fashion, was among the group’s most lucrative divisions.

Currently, most initiatives in the fashion industry are limited to a form of “circularity” that, at best, can only be considered tangentially related to degrowth. As highlighted in the Circularity Gap Report, efforts are primarily focused on improving efficiency in the early stages of the supply chain and developing models that keep products in circulation—through repair, rental, resale, and reuse. However, these attempts, still in their infancy, fail to truly challenge the dominant take-make-waste linear production system. Angela Baidoo, writing for The Impression, points out that even a diluted version of degrowth struggles to scale—further proof of how the harsh reality of capitalist markets stifles any serious challenge to the existing production paradigm. If truly implemented, degrowth would mean producing less, but with higher quality standards, raising the bar for working conditions and care at every stage of the supply chain. As Olya Kuryshchuk, founder and editor-in-chief of 1 Granary, states, «It means taking care of workers and the planet, not producing without first considering the human and environmental costs.» An approach that, while seemingly simple, clashes with an industry where growth has been synonymous with success for decades. But, as Kuryshchuk also observes, for independent brands, there is no strong correlation between expansion and success. The new generation of creators must urgently question what it means to have a sustainable fashion business today, challenging outdated structures and seeking creative models that integrate environmental and social impact into their production processes. A critical analysis is also needed regarding who and what is chosen to grow. In an industry where expansion is seen as the sole measure of success, it is essential to redefine the parameters of success, questioning the benefits of unlimited growth.

oh how i love the artistry, craftsmanship, and creativity of fashion but my hate for capitalism is just growing larger everyday

— /J\ (@_joulian_) October 15, 2024

So far, all businesses that have adopted the concept of degrowth in their economic model have relied more on sustainable ideals than on the theory’s anti-capitalist dialectic. In 2022, Vogue Business wrote about the first brand founded on degrowth principles, Early Majority, which focused on outerwear and debuted with a collection of seven "subversive" pieces designed to be worn across four seasons, depending on how the different components of the garments were combined. In essence, buy less but buy better. However, as evidenced by both its official Instagram page and the brand’s absence from the web, Early Majority did not survive beyond two years—although last August, it announced that «this is only a goodbye, not a farewell». This is precisely why the degrowth model remains a great unknown. Between the lack of empirical evidence and the stigma many brands hold against discussing and adopting such a model—as highlighted by Aerielle Rojas in her panel on the implementation of degrowth in fashion at the Global Fashion Conference and in the Textile Exchange report—there is no certainty that applying this economic approach would actually benefit all stakeholders involved. Moreover, ultra-luxury brands (such as Hermès and Chanel), while adopting rhetoric somewhat aligned with degrowth, have also increased their prices, fundamentally contradicting the anti-capitalist concept at the core of the theory. At the same time, it is now undeniable that the business model of the entire luxury industry is no longer adequate: as time goes on, the industry as a whole is edging closer to a state of unprecedented precariousness.