Could the resell market be the future for fashion brands? Rivals? Allies? Fashion cannot afford to remain in doubt

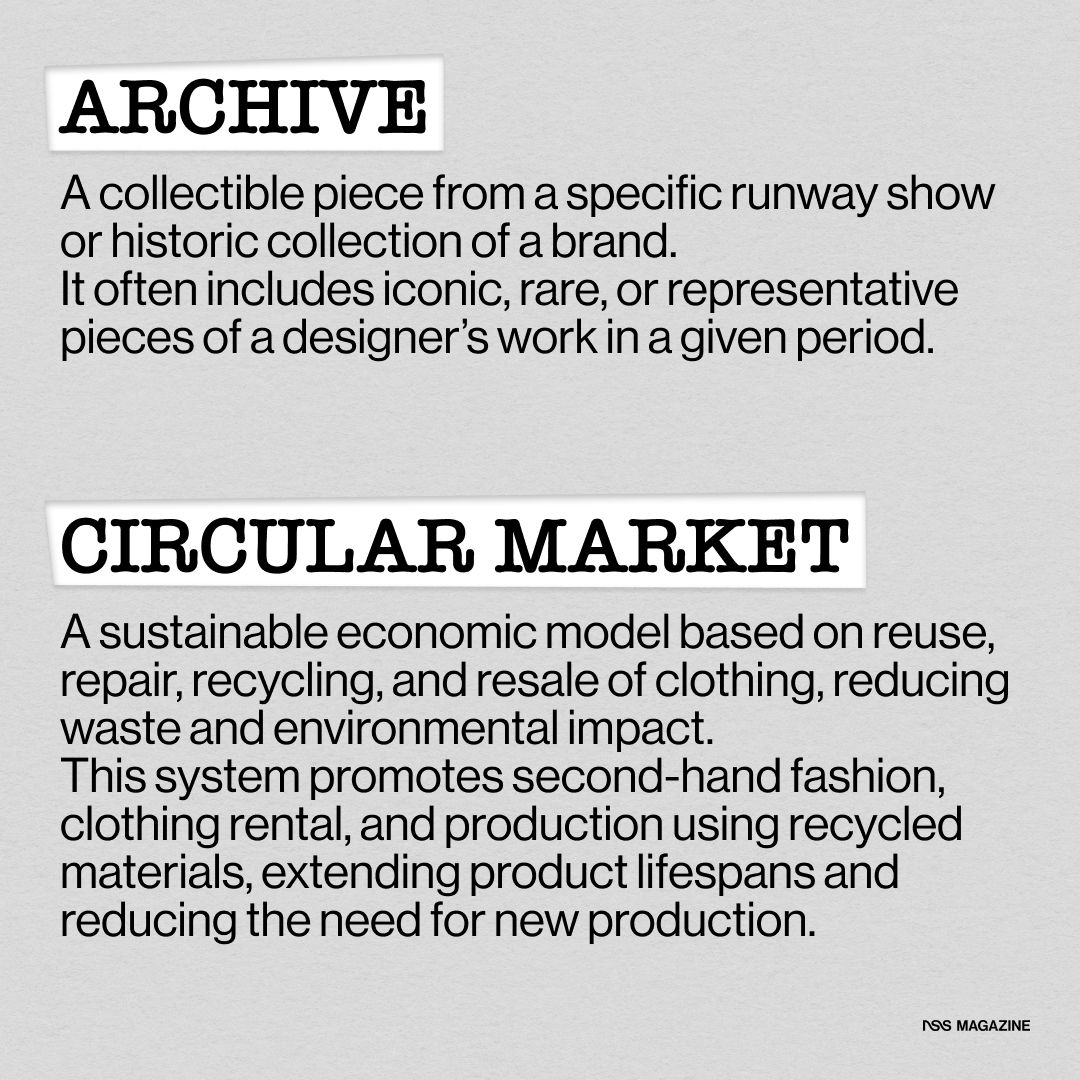

The fashion industry, and particularly the luxury sector, has always been associated with exclusivity, but only as a selling point. It is no secret that the growth trajectory that has led numerous commercial brands to grow exponentially in the last decade, only to be interrupted by the lockdown, was fueled by a democratization of luxury and specifically by the proliferation of so-called “entry-level items” that transformed customers' aspiration into sales. Fashion claims to be for a few, but operates based on the sales of the many – a contradiction even more exacerbated by the dual growth of prices and the secondhand market. A large part of those who buy branded items today do not buy them from the brands, but from off-price channels like outlets and sales, and of course on resale platforms. And now that the crisis of fashion brands is more acute than ever, it might be the right time to ask whether the luxury industry should rethink its strategies. Instead of focusing on selling many different products, companies could benefit from focusing on reselling their products, aiming to sell the same items multiple times.

This idea not only leverages the enormous momentum that secondhand is experiencing, now a true alternative form of consumption but also offers brands an opportunity to have more control over the products and a more solid customer loyalty base. The resale market, particularly in the United States, is growing rapidly: according to The State of Fashion 2025, sales of secondhand items grew 15 times faster than the clothing retail sector in 2023, and this year they are expected to account for 10% of the global apparel market. The segment could develop at a compound annual growth rate of 12%, reaching 350 billion dollars in the next three years. In fact, not only do 41% of consumers looking for clothing deals now turn to secondhand stores, indicating a strong change in shopping habits, but 60% of consumers believe they get more value by purchasing secondhand clothing, and platforms like Vinted report that 65% of their buyers prefer purchasing fewer items but of higher quality, rather than more inexpensive items.

First experiments of a new model

@emma.rogue Replying to @heideggrrl here r some tips on how to get started reselling if you have no idea where to start. Gonna make this a series, ask more q’s in the comments! #greenscreen original sound - emma rogue

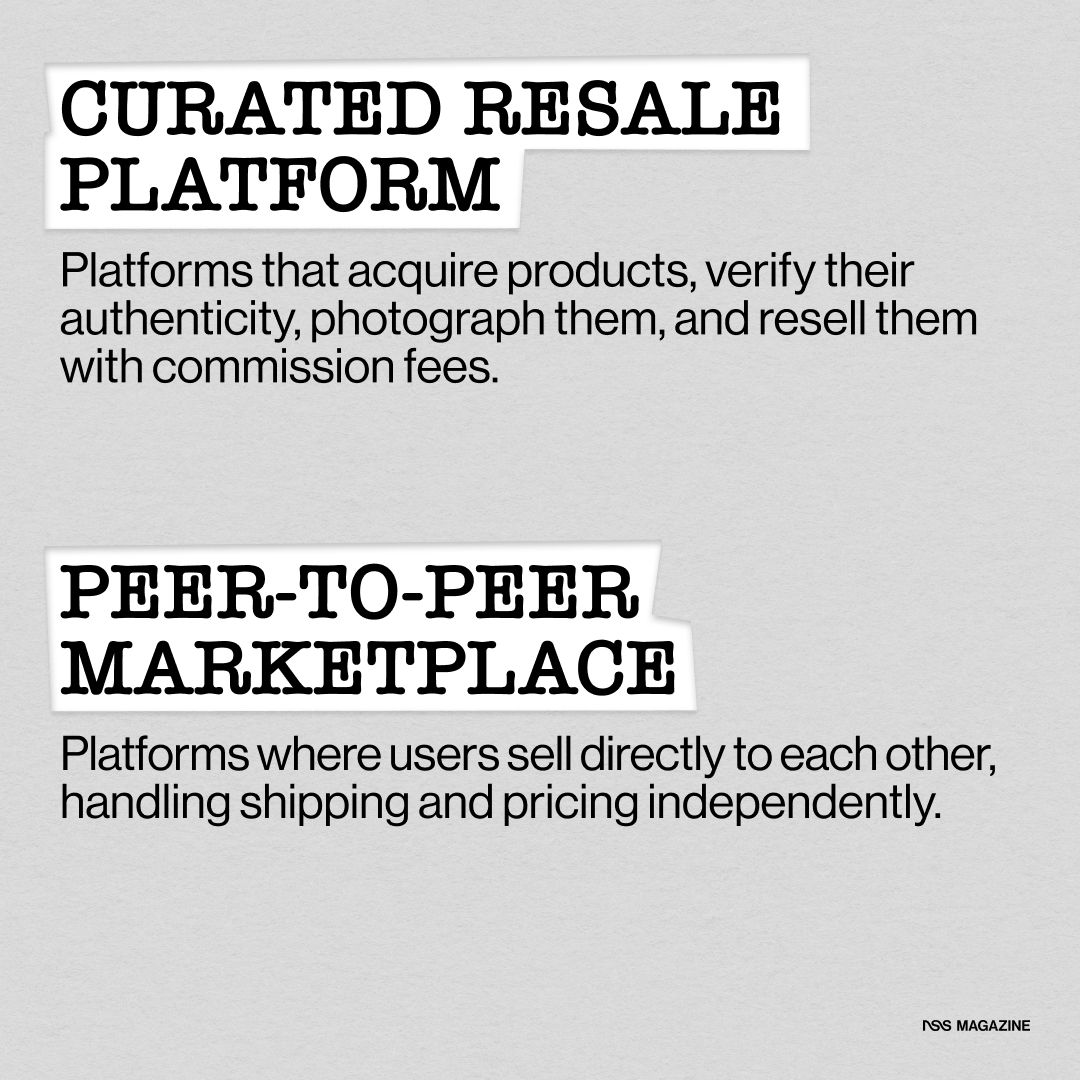

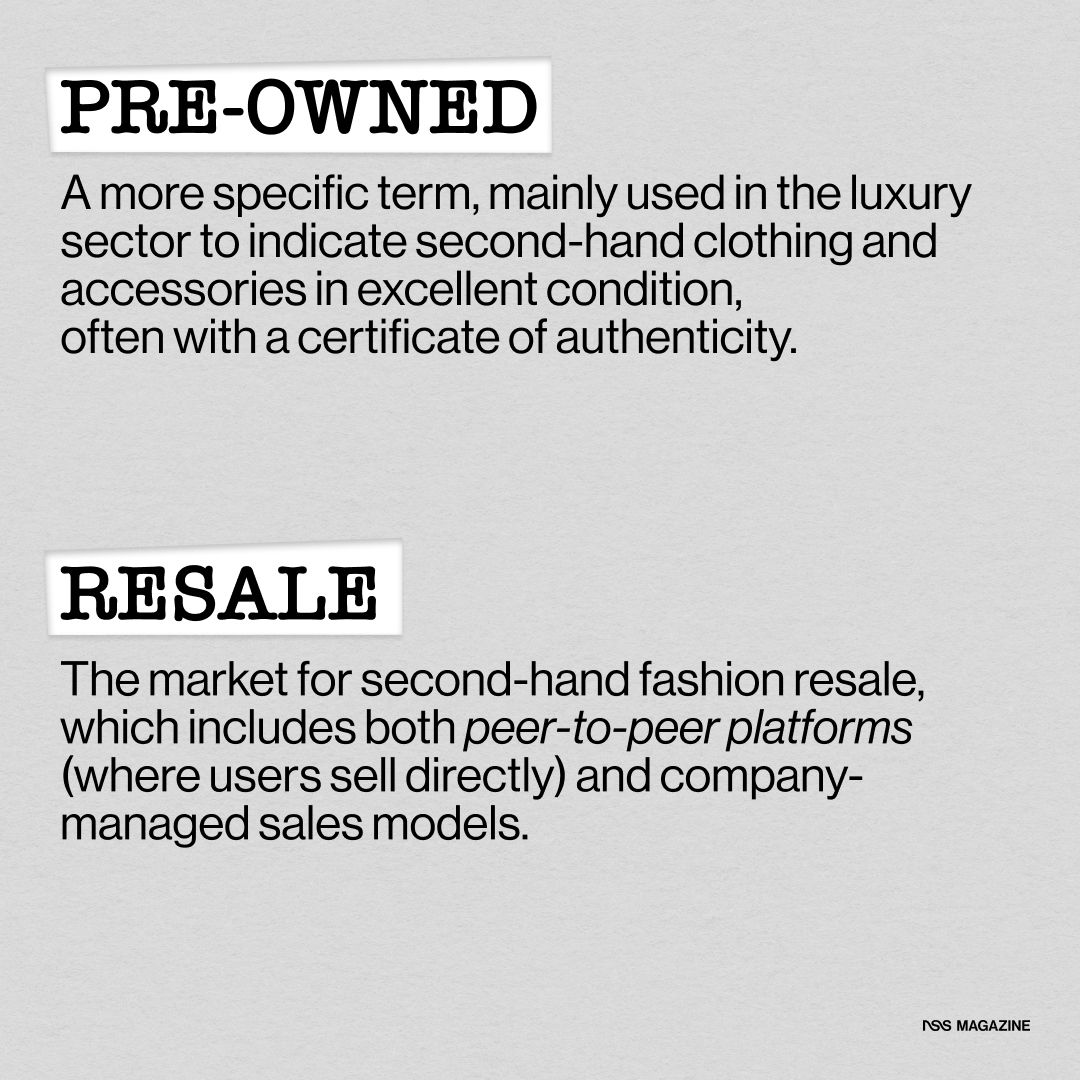

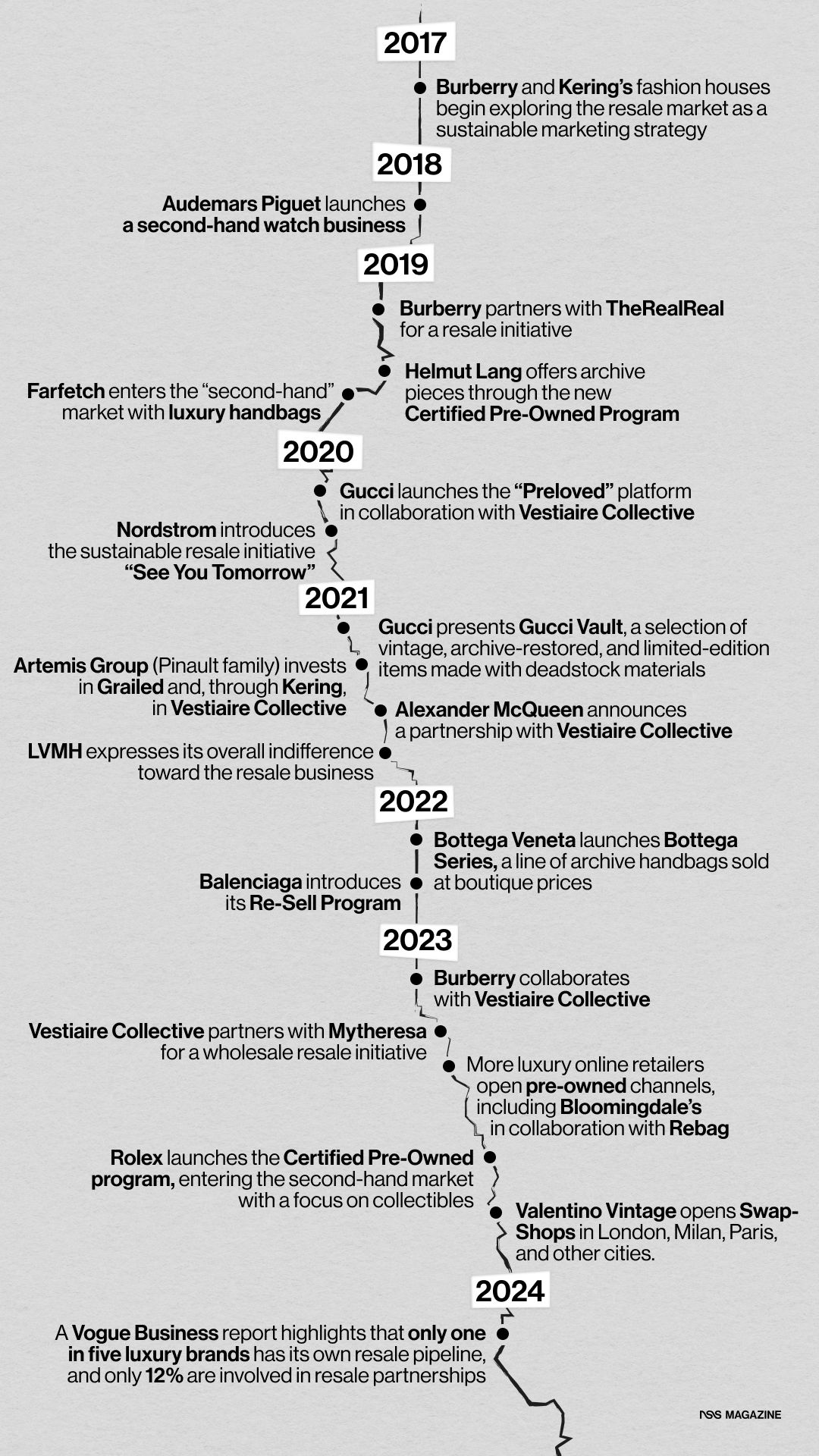

Luxury brands, of course, have seen significant development in the resale market, which grows four times faster than the primary luxury market, according to a study by the Luxury Bocconi Student Society. While the luxury market grows annually by 3%, the resale sector grows by 12%. According to estimates from that report, the luxury secondhand market is already valued at 24 billion dollars and is expected to reach 64 billion dollars this year, with luxury goods in the resale market doubled the growth of the entire fashion industry. In response to this trend, many brands are experimenting with ways to exert control over this expanding market to ensure their products maintain value and desirability. Beyond the issue of sustainability, which is important but may no longer motivate consumers, the reasons for this growth are twofold: the first is that resale products have more honest prices than luxury, which has now gone into overdrive; the second is that many buyers are attracted by the authenticity and uniqueness of the items available on resale platforms, such as limited-edition or vintage goods, which are often no longer available through traditional sales channels. Attempts by institutional fashion to capitalize on this trend have been varied and remain on the level of single experiments. Usually, they are collaborations with resale platforms offering store credits or exclusive experiences for customers who trade in their items. Some have taken more drastic solutions: Richemont, for example, which owns brands like Cartier and Piaget, acquired the resale platform Watchfinder in 2018, gaining the power to directly influence the resale market for their luxury watches and counteract the sale of fakes, but most importantly giving Richemont control over the sales process to prevent damage to the brand’s image.

LVMH declared itself essentially indifferent to this business as early as 2021, but in the last five or six years, both Burberry and the maisons of Kering have started flirting with resale based on a marketing strategy strongly focused on sustainability. In 2019, Burberry collaborated with TheRealReal; in 2020, Gucci launched its "Preloved" platform in collaboration with Vestiaire Collective, and the following year created Gucci Vault, where vintage or refurbished archive items were sold and offered limited-edition products made from deadstock materials. The project worked in some ways, such as highlighting the beauty of historical products and bringing young brands and designers to the forefront, but it did not become a true resale platform as it was dedicated to a few collectible pieces sold at boutique-level prices – thus eliminating the economic advantage that is somewhat the foundation of secondhand. In 2021, Artemis Group, the Pinault family became an investor in Grailed and, through Kering, invested in Vestiaire Collective, with which Alexander McQueen announced a partnership. In 2022, Bottega Veneta launched Bottega Series, offering archive bags, but still at boutique prices, and Balenciaga launched its Re-Sell Program. In 2023, Burberry collaborated with Vestiaire Collective, while last May, another experiment (this one seems successful) took place in the wholesale world with the partnership between Vestiaire Collective and Mytheresa, the opening of pre-owned channels on luxury online retailers, and also with the one between Bloomingdale’s and Rebag. Last September, Rolex presented the Certified Pre-Owned program, which gave access to the vast secondary market for luxury watches, but with a focus on collecting. But, as mentioned, at least in classic fashion, these have been experiments. As stated in a Vogue Business report: “only one in five luxury brands has a resale pipeline owned by the brand, while only 12% are involved in resale partnerships.”

A matter of convenience

Also, very weird that people who clearly value appearing richer than they are would scoff at secondhand when TheRealReal, Vestaire Collective, Tradesy, Re-See and Designer Revival have ALWAYS been the secret to how the fashion girlies get our designer...secondhand.

— Lakyn Thee Stylist (@OgLakyn) October 20, 2022

Such initiatives align with the growing desire for sustainability but are actually about accessibility or, in other words, saving money. The State of Fashion 2025 indicates, for example, that over a percentage between 60% and 75% of consumers in both the USA and the UK are looking to save money on fashion "often" or "as much as possible." As consumers, particularly those in the premium market, seek so-called value-for-money, meaning they try to avoid inflated fashion prices by looking for bargains, resale could become a channel to attract and retain customers – but only if brands approach the resale of used items as an off-price channel and not at full price. The resale business revolves around savings, and therefore if a brand intended to resell used and refurbished products with a 30% discount on the original retail price, every initiative would be a failure – but there are significant customer loyalty benefits if the two channels are kept properly separate. Notably, according to The State of Fashion, 23% of premium shoppers already use resale platforms to save money, and many prefer to buy fewer items but of higher quality rather than more cheap items. But while acquiring new customers via resale channels is difficult, it is still possible to retain existing ones. Many of the Pre-Owned programs that have appeared in recent years, without a true systematic approach, allow customers to trade in unwanted items in exchange for new purchases or store credits. Valentino did something similar with the Valentino Vintage initiative, for example, which dealt with almost archival items and could almost only interest collectors – interesting for wealthy regular customers but irrelevant in the vast sea of the second-hand market where price-cutting is in play, and the margin game doesn’t work.

Moreover, as early as 2021, surveys from McKinsey revealed that 9 out of 10 consumers who buy second-hand luxury goods are also buyers of new products, indicating that resale is not cannibalizing full-price purchases, but complementing them. The same study reveals that a percentage between 75% and 80% of traditional luxury customers are not interested in reselling – a figure that is confirmed in The State of Fashion 2025 by comparison. In the most recent report, it is stated that those over 50, or “Silver Spenders” will drive 48% of global spending this year, and therefore, fashion brands should focus particularly on them. This customer segment does not follow trends, is interested in the functionality of products, but most importantly does not have the same core motivations as Millennials and Gen Z, whom fashion has been paying attention to so far: specifically, the report states, "The Silver Generation has 7 to 17 percentage points less likelihood of turning to non-traditional fashion channels, such as resale." In general, therefore, several studies (including those from McKinsey from a few years ago) show that brand equity and existing sales would not be significantly affected by a resale service just as they are not affected by outlets. Generally, the two channels exist on separate planes due to a psychological factor, as regular customers in the luxury sector tend to avoid buying second-hand products because they place great value on the fact that the product is new, unused, and has no previous history. The perception of exclusivity, freshness, and uniqueness is fundamental to them and represents an essential element of the prestige tied to the product – incidentally, these concerns match those of luxury brands who, for example, do not want to see their products sold by others without control and margin over the price, and without the dedicated customer experience.

Me on vestiare collective https://t.co/HwQ9QbQ3RW

— Lys (@inherlane_) January 31, 2025

The decision to enter the resale market is not without challenges. On the sustainability front, for example, Delphine Williot, head of Fashion Revolution policies, said in an interview with Time Magazine that in order for resale to be effective in reducing environmental impact, brands must reduce overall production. Offering resale platforms, luxury brands must also face concerns like authentication, storage, refurbishment, and setting up (we assume) an e-commerce service or a physical location like Gucci Vault was years ago. The financial implications for brands deciding to enter the second-hand market are not few. While partnerships with resale platforms like The RealReal or Vestiaire Collective relieve brands from the logistical burden of creating their own platforms, the model offers lower profit margins as resale platforms typically charge commissions ranging from 20% to 40%, which can erode brand revenues. On the other hand, creating one’s own resale platform would keep margins and profits high but requires investments in logistics, authentication, and supply chain management – not to mention the presence of third-party partners. This seems, in part, to be a double problem that currently keeps the two markets separate: on the one hand, fashion does not want to lower prices, and if they do, not by much, and does not want to distribute its products far and wide; on the other hand, there is the second-hand world that operates based on economic convenience and, in essence, on selling branded products at premium brand prices, if not fast fashion. It is the nature of the two markets that assign different values to the margins of each sale and, in some ways, their respective limiting characteristics coincide with the value propositions both markets offer to customers.

Two different profit ideas

@georgejeffersonn Should you sell your clothes on Depop or Vinted? #depop #vinted #resell #georgejeff original sound - George Jefferson

Despite the volcanic growth of the second-hand market, profitability remains a difficult goal to achieve for all major companies in the sector that, in general, struggle to generate profits, despite the continuous expansion of the market. The problem is that in the second-hand fashion sector, companies often prioritize growth over profitability, leading to significant capital investments that have not yet produced profitable results, and therefore, the high costs associated with reselling used goods often exceed potential revenues. As explained by BBC last March, the main example of this problem related to a marketplace dynamic similar to Farfetch's (which also didn’t work) is Depop, acquired by Etsy in 2021 for $1.6 billion, but in 2023 it posted a net loss of $69 million after Etsy decided to devalue Depop by $898 million in 2022. Similarly, ThredUp faced similar difficulties: the increase in operational costs associated with selecting and processing individual products is one of the main reasons for these difficulties that the expansion of operations and business has not been able to solve. According to Financial Times, The RealReal is in the same situation: despite an 11% increase in revenue in the third quarter of 2023, the company remains unprofitable and is not expected to reach net profit before 2028, according to analysts at Visible Alpha. Even eBay generates 80% of its revenues from new products, rather than second-hand items. The only fully profitable company example is Vinted which, in 2023, recorded a net profit of €17.8 million, after a net loss of €20.4 million the previous year. A recovery driven by a 61% increase in revenues, reaching €596.3 million in 2023, which experts attribute mainly to its business model, which does not charge sellers commissions, allowing the platform to attract a broad base of sellers and buyers. Furthermore, Vinted generates revenues through alternative streams, including advertising, shipping services, and payments. This model has allowed Vinted to carve out a niche in a highly competitive sector, while its expansion into new categories, like electronics, offers the potential to further diversify revenue sources. Additionally, Vinted's extraordinary growth led to a €1.5 billion increase in its valuation in the past three years, bringing its current value to €5 billion.

One of the factors that weighs heavily on costs is the labor-intensive nature of handling and selling products, a highly inefficient process that starts from the digital and physical storage of the products themselves and the evaluation and authentication processes – all manual so far. The volumes of products do not help: the enormous amount of fast fashion clothes makes it harder for resale platforms to differentiate and get higher prices for the items they sell, so much so that some, like Vestiaire Collective, have completely banned fast fashion brands and others, like Vinted, have created “areas” specialized for luxury items only. In the case of platforms that acquire used products and resell them without entrusting shipping and buying/selling to users, there is also the issue of operational costs and their impact on prices: if one goes into the second-hand world to save, the rising costs to handle and sell second-hand clothing make these deals increasingly harder to find. To address these challenges, several resale platforms have started to adapt their business models.

A third way?

Regardless of these difficulties, the second-hand market has huge potential. As suggested to BBC by Liz Ricketts of The Or Foundation, reducing the excess production of new clothing by 40% could help restore balance and increase the value of second-hand goods. Vinted's approach, which eliminates commissions for sellers, expanding its user base and diversifying its revenue streams, allowing sellers to retain a larger share of the profits from their sales, has proven successful and is being adopted by other platforms, including eBay and Etsy, which have recently eliminated commissions for most private sellers. Thinking of a link-up between luxury and second-hand, it is imaginable that brands and their managers do not want to take on additional management costs as they have already considered how overproduction has devastated their finances between storage and disposal of unsold goods. But it is precisely the unsold product that ties into the problem: so much is produced due to the economy of scale, and if they try to produce less, the damage falls disastrously on the supply chain, which no longer has orders to cover costs, as illustrated by a recent report from Il Fatto Quotidiano. The most immovable obstacle remains the race for margins on one hand and extremely high prices on the other.

@nssmagazine Explore the archive selection at Shop The Story. Discover more in-store at Via Melzo, 10, Milan @Shopthestory #archive #archivefashion #fashiontiktok #tiktokfashion #vintage #vintagestore #cool #archivestore #milano #milan #shopping #portavenezia suono originale - nss magazine

A possibly more sustainable approach could concern “third spaces”, alternatives to the classic outlet and platform – informal vintage shops managed by the brands themselves where the used nature of the items for sale would justify a smaller investment in customer experience, but would still offer a new type of experience more akin to the classic exploration of the vintage shop that practically everyone already romanticizes. If these spaces were placed in urban contexts far from the classic luxury shopping districts (imagine the difference between Montenapoleone and Via Mora in Milan, where various small shops, including Bivio and Cavalli & Nastri, sell products from all the major luxury brands, or in Paris the aesthetic distance between the Champs-Élysées and Avenue Montaigne with a neighborhood like Le Marais) they could not only keep the channels separate but also attract an entry-level clientele less intimidated by the sustainability and relative formality of boutique shopping. However, this would mean for brands reconsidering their prices and margins in this segment, perhaps without completely rethinking their entire business model but certainly thinking about an alternative business model. And given the state of the luxury industry today – an alternative would need to be found.