There's a logo, but you can't see it Logo? No logo? Why not both?

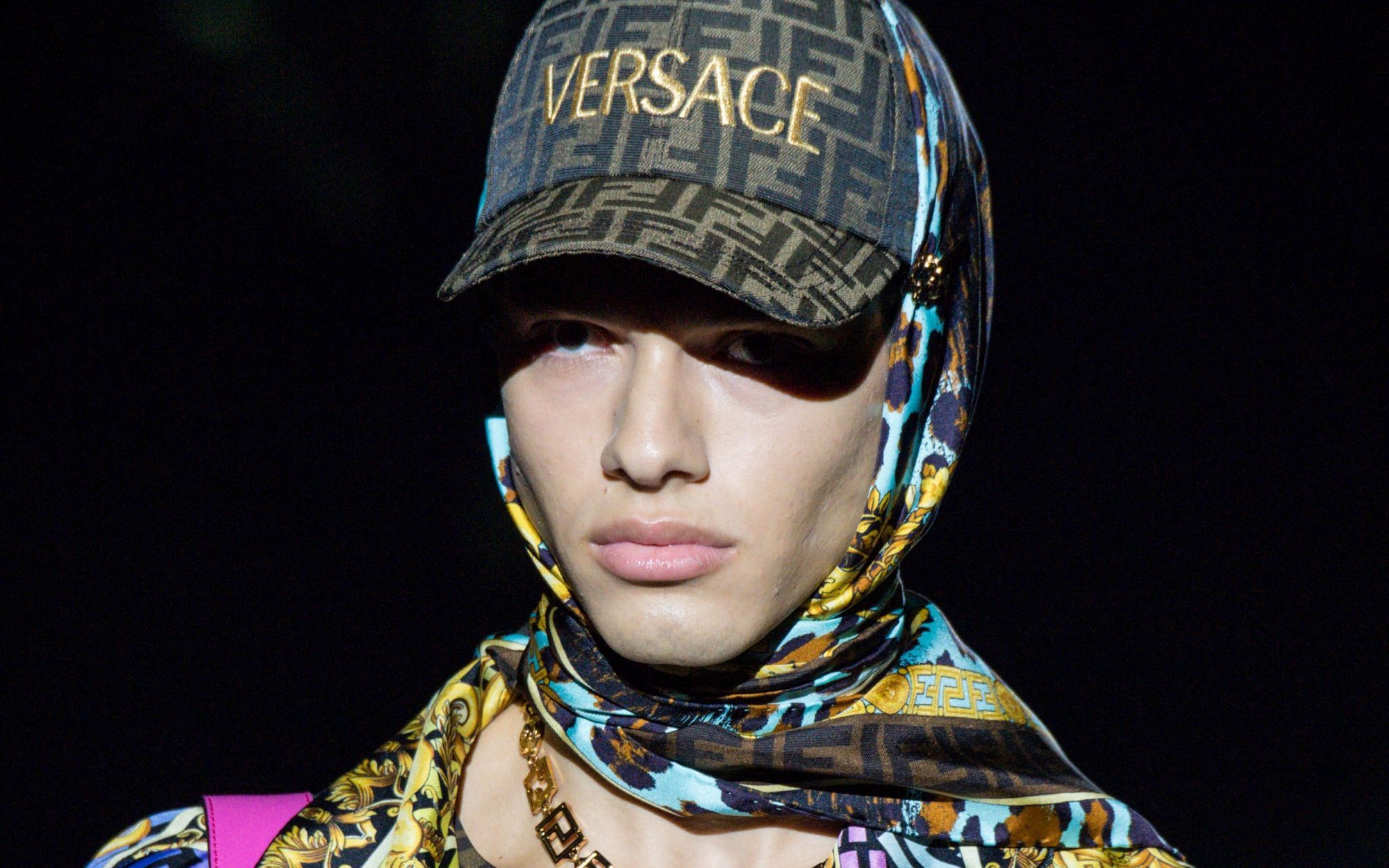

It is well-known that fashion is cyclical. And the constant shift in styles also affects logos. Ten years ago, the fashion world re-explored them in all their exuberance, sometimes transforming them into all-over prints where superficiality often exhausted the entire design. "Logomania" was the term used at the time to describe this trend, driven by Virgil Abloh and his post-modern reinterpretation of the logo, by Alessandro Michele from Gucci and Demna from Balenciaga, and especially by Gosha Rubchinsky, whose career was rightly cut short but who actually helped normalize this specific type of ostentation. In any case, for a certain period, logomania was everywhere—so ubiquitous that it quickly became tiresome. After the lockdown, the fashion community emerged changed, craving comfort but above all craving creativity, material quality, and innovation. Thus began the era of logos with unexpected placements, vacant or non-existent, of material luxury that had to speak for itself—a period perhaps refreshing but somewhat dull. And just now, at the turn of a new period, logos seem to have returned but in a different form: semi-visible, prominent yet discreet at the same time. This is the era of quiet logomania. Among the various looks that could be cited as examples from recent shows, the most emblematic might be a lime green leather dress from Gucci, seen at the last fashion week, where the logo was embossed only under the top edge of the dress: invisible from afar but the first thing you notice up close. Elsewhere, almost every look from Dior’s latest women's show featured a tiny white logo printed on the right hip; at Loewe, there are plenty of leather tags that don’t even indicate the brand's name, placed at strategic points on jackets and sweaters, often behind the neck, which is also where Prada has begun placing distinct triangles, or triangular cutouts, recognizable as logos for those who know.

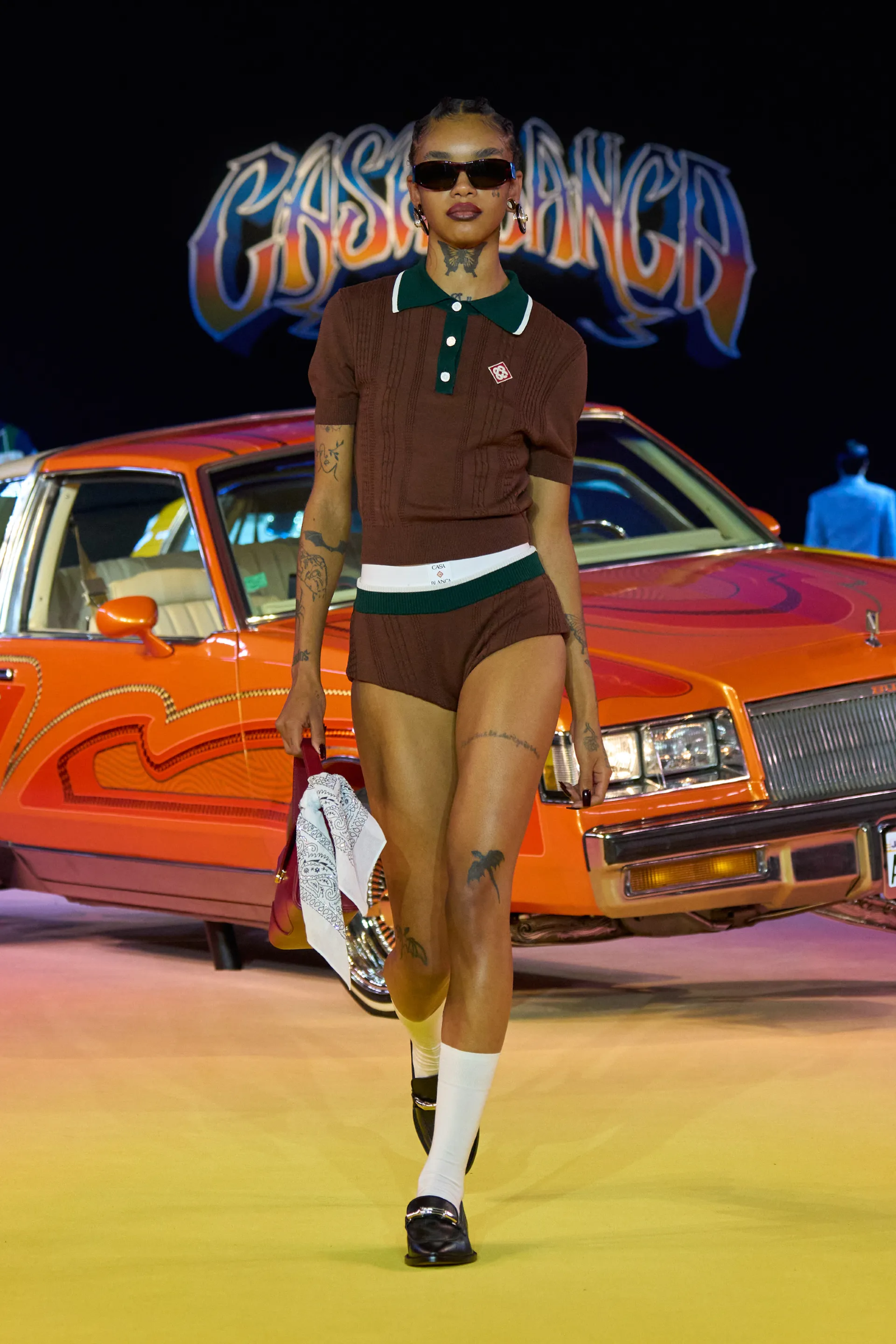

But there are many examples: logos embroidered in discreet places on a white dress by Chanel, or transformed into abstract graphics like Marine Serre or Amiri, and even placed on labels reminiscent of certain '90s sportswear or, more classically, on the left chest as Miu Miu and Balenciaga have been doing for some years, along with Valentino and, surprisingly, Louis Vuitton, which nonetheless has not given up on logomania, nor has Gucci. At Off-White or Courregès, logos are very central on the chest but small or tone-on-tone, still not dominant; Charles Jeffrey Loverboy and Louis Gabriel Nouchi, on the other hand, have thought of tags placed on visible boxers that are only noticeable if observed closely; DSQUARED2, for its part, has always placed a tiny logo on the jeans' fly. But the point here is not the disappearance or appearance of logos but rather the compromise found in their placement: they must exist, be visible but discreet, while avoiding turning the wearer into a walking advertisement for the brand. Trends coexist nonetheless: at Prada and Miu Miu, there are both sweaters with maxi-logos and discreet triangles on the back of the neck; at Gucci, subtle branding such as colored bands coexist with garments covered in the GG motif, as is the case at Loewe, Louis Vuitton, Dior, and so on. The public is interested. According to the WSJ, «Net-a-Porter saw searches containing the word “logo” increase by 444%. Mr Porter, which caters to men, recorded a 103% increase over the same period» while «since the end of July, Mr Porter has recorded a 400% increase in searches for Loewe logos, including the brand's anagrammatic motif composed of four spiraling cursive “L”s». The reason for this comeback is actually easy to understand: when a customer buys a simple navy blue cashmere sweater for nearly two thousand euros, they want at the very least for it to be clear which brand it belongs to.

The presence of these logos, therefore, retains its original function of elevating ordinary designs and justifying their price, as well as signaling status. Their widespread use is also related to the rise of dupe culture, and thus products that simulate the aesthetic of branded items without counterfeiting the brand itself; with the somewhat obsessive relationship modern fashion consumers have developed with the visual aspect of products, that is, what can be communicated through social media; and above all, with the bet that brands are making on what, quoting a 2010 study, the WSJ describes as “horizontal signals”, i.e., recognition elements that allow people of the same social class to communicate with each other – while “vertical” signals like mega-logos or monograms serve to communicate status from the bottom up. Interestingly, this type of branding, especially in the form of a small chest logo, is primarily associated with Polo Ralph Lauren, which just last week reported very strong financial results ($1.7 billion in sales for the second quarter of the year alone) and indeed represents a unique case of a brand that speaks to various market segments through different lines without diluting its appeal. In short, if a garment is branded, it may not be immediately visible, but it absolutely must be recognizable – for everything else, there's Uniqlo.