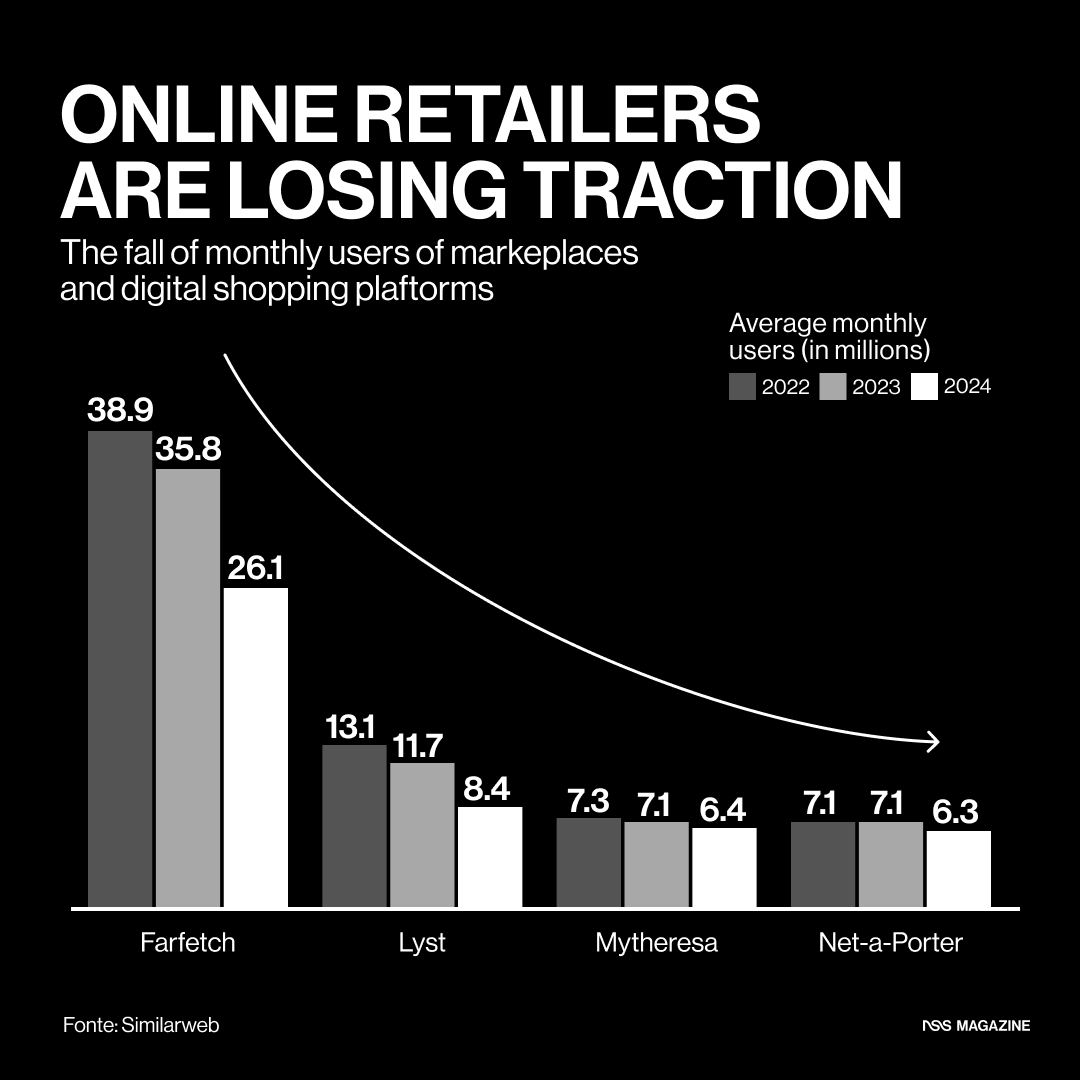

The bubble has burst: the collapse of luxury gray markets It was addiction, salvation - and with its collapse it could drag many away with it

Last year, when the triumphant march of fashion growth continued stronger every quarter, one of the industry’s most hidden secrets came to light: that of the grey markets. The semi-underground network of legitimate products distributed through unauthorized channels or by multi-brand wholesalers or original manufacturers, often sold at prices 15% to 35% lower than those intended for the target market. The existence of these channels, as we wrote in our first investigation on the subject, «keeps retailers' margins high despite the retail sales crisis, and helps brands register healthy growth percentages, but falsifies the actual performance of all parties involved». Currently, the practice is not strictly illegal – thus making these markets “grey” in the eyes of the law. Yet, despite attempts to contain the phenomenon with distribution clauses present in contracts with retailers, the brands themselves have started to foster this practice which for years created the illusion of healthy growth and now, with the luxury sales crisis, threatens to collapse and change industry dynamics.

The evolution of the grey market: from wholesalers to direct sales

We spoke with two digital consultants who work with numerous brands and platforms about what has changed within the mechanisms of the parallel market: «Today, the grey market has changed because wholesalers' demands have changed. The product is sold directly to customers through digital channels. Marketplaces today represent the new parallel», explain the experts who preferred to stay anonymous. In short, retailers are being forced to place very large merchandise orders to meet a budget threshold that allows them to keep purchasing, even if the products aren’t selling. To offload these luxury goods, retailers «are channeling and distributing them through platforms that used to be three and are now two hundred, diversified across all areas from China to India, Australia, South America, and the Middle East». In the past, retailers selling on the grey market did so to other resellers who essentially bought merchandise in bulk from them, allowing retailers to recover their sales investment while freeing up unsold goods, all while keeping commercial channels open with brands. But now that brands want to sell much more to fewer retailers, an accumulation has occurred which, following the collapse of luxury spending, needs to be cleared not through wholesale orders but through retail sales via platforms where these luxury goods are sold at steep discounts through multi-brand e-commerce «where no one knows who buys or sells the product».

@libbylemonlines I know its on sale at farfetched but surely thats too cheap? I don’t get it

original sound - Lib

But this new practice is much more demanding in terms of time and resources, as well as a strong departure from past bulk orders «because you sell one piece at a time, nor are you paid upfront, as there is obviously a risk it won’t sell», the two insiders explain. Brands «simply link their stock to the platforms, offering their assortment at a very competitive price». This change in workflow demonstrates, to paraphrase the famous saying, that low tide lowers all boats: «The parallel market was very profitable in the past», they say, «it was used to generate margins, but now those margins are gone, so they are trying to get rid of excess stock». Of course, it would be impossible to name the brands adopting this practice – which are nonetheless almost all at the most unexpected levels of the market. «Let’s take an example», the two experts say, «on my official channel, I never discount anything. My product is always perfect, always in place, no sales – nothing. But then I use a specific platform to offload all the items that I can’t sell on my site because 87% of that merchandise consists solely of carry-overs. Many brands have approached us wanting to access these platforms themselves». The notable aspect is that, while brands previously tacitly accepted a practice carried out by wholesalers, now they have taken matters into their own hands. «Today, the parallel market remains profitable if they manage it themselves», they explain. «Brands have found interlocutors in certain areas of the world where their distribution was lacking and have turned to buyers who guarantee volume and market presence».

High Prices, Low Sales, Short-sighted Managers

Besides emptying warehouses discreetly, the grey market is important «because the demand on the parallel market helps to understand how your brand is performing. Today, desirability is determined by the price at which the buyer is willing to pay for that brand». But there has been a «paradigm shift» due to luxury prices getting higher and higher, making the goods unappealing even to those who would buy them at a discount. But just because the demand for luxury seems stagnant, it doesn’t mean that the demand for clothing is exhausted—quite the opposite. Simply put, brand positioning is shifting and customer tastes are changing: «While no one used to wear Carhartt a few years ago, now someone who normally wears Saint Laurent does». The rise in prices has, so to speak, broken the luxury market, giving rise to a segment of brands that the two consultants define as beyond luxury, represented by Brunello Cucinelli, Kiton, Loro Piana, Hermès—for whose extremely expensive products «luxury is clear». For the rest of the brands, things are different: «Can a brand justify a hoodie costing 1200 euros? In the traditional concept of luxury, it should, but now it can’t anymore».

Brunello Cucinelli reporting 9% growth for the quarter, after LVMH reported a 4.4% drop in revenues, suggests that it's the mass-luxury market that is shrinking, while the truly wealthy continue to spend. That's exactly what happened in the 2008-2009 financial crash.

— Christina Binkley (@BinkleyOnStyle) October 17, 2024

By selling banal designs, luxury brands have ended up competing with mass distribution, which obviously wins the comparison since it costs much less. The problem, therefore, lies in this «pursuit of numbers and volumes» which has led the system to first overinflate and now implode on itself. The root of this problem lies in the policy and in those who implement it: the managers. While in the past brands were born from the companies of the producers (think of companies like Zegna and Loro Piana, but also groups like Blufin or Gilmar) which maintained a certain stability for entire decades, in the world of stock listings the turnover is much faster. This leads to greater flexibility but completely destroys strategic foresight: «Normally, managers in these companies last two to four years and earn insane bonuses for growth», explain the two consultants. «So they try to pump sales to the extreme because they know their time is limited—but of course, this doesn’t allow them to develop a long-term strategy».

Unpleasant Antidotes and Useless Palliatives

@guidusguidum kinda fell in love with the balenciaga skirt #luxurysale #fashioninspo #privatesale original sound - milanostreet

Due to this strategic short-sight, caused by managers who change too quickly to support long-term strategies, the immediate solution to the problem of unsold goods has become sales events, which are multiplying and becoming more expensive but also more profitable. One client of the two, who organized one to clear out inventory before renovating the stores, «made as much as they normally make in six months in just thirty days, one million euros, discounting goods by 50%», they explain. «The problem is not that people no longer buy luxury: they no longer buy luxury at those prices. Why is Vinted still growing? Not because people like to buy secondhand. People like buying luxury goods at a price they can afford». For example, it was recently reported that 50% of Burberry’s profits and 30% of the brand's global sales come from its 56 outlets, while our interviewees also revealed that a well-known Milanese brand makes one hundred million a year from a single outlet in Tuscany – «outlets are the real gold mine», they revealed. Despite this, prices keep rising, and the idea of lowering them is taboo.

The solution could be twofold: on one hand, «rationalizing products or reducing production, to limit the number of items available since brands have flooded wholesale to grow numbers»; on the other hand, «if the big groups don’t realize that sooner or later they will have to lower prices, I believe we will enter an irreversible process, and luxury will remain only and exclusively for a very few». In short, the problems of the parallel market are nothing but the problems of fashion itself: these markets have always served as a “thermometer” to understand which product and which brand is most in demand, much like the presence of counterfeits and imitations ultimately signals the success of a certain brand, even if it theoretically harms the business. «There is no future for companies that think they can survive by just cutting costs», warn the two, pointing to the solution to the collapse as «multichannel strategies and lean management of companies». But how can one manage an international empire in a lean way? And especially, in the new world fashion is facing, can luxury be represented by an international empire as massified as McDonald’s or Coca-Cola? The rise of nationalism and the multiplication of fashion weeks around the world, economic protectionism promoted by the USA and China, as well as the thinning out of artisanal excellence, indeed suggests a different future, one populated more by national kingdoms than global empires. And what if the nationalization of fashion were the new globalization of the industry?