Morphology of mannequins On why they change and what they say about us

Mannequins are a constant in the history of fashion, an element that, like trends, is in continuous evolution. If the clothes we wear represent us, the fashion we aspire to embodies our ideals. Not just political or philosophical (like rejecting fast fashion or embracing minimalism, for instance), but also physical: clothing is a means of expression, the body its canvas. What we see on the runway is nothing more than the final sedimentation of all the socio-political events that preceded it. For example, after World War II, shop mannequins became thinner due to the crisis and two centimetres shorter, while in the '80s, they started sporting abs. Faced with a world torn apart by wars and late-stage capitalism, fashion responds to public uncertainty by offering a false sense of security through ready-to-use aesthetics that tap into nostalgia, such as Cottagecore, Dark Academia, and Indie Sleaze. Even mannequins have fallen victim to this simplification: with the rise of quiet luxury, collections oversaturated with accessories, and straightforward product designs (making them easier to sell), mannequins are becoming indistinguishable, sometimes disappearing from shop windows altogether, replaced by minimalist hangers or art installations. So, don't blame a brand for using mannequins that are too thin—they're merely a sign of the times we're living in.

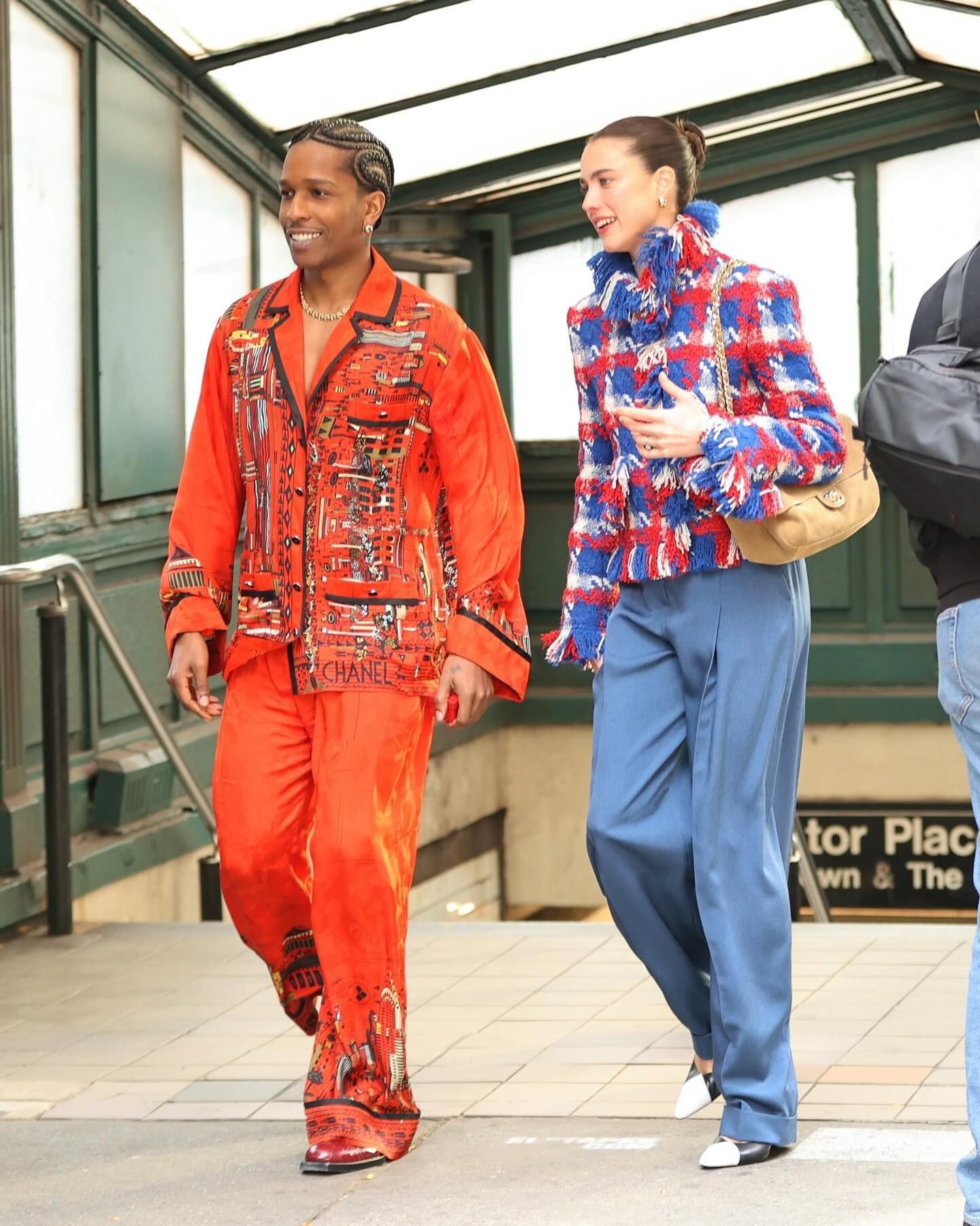

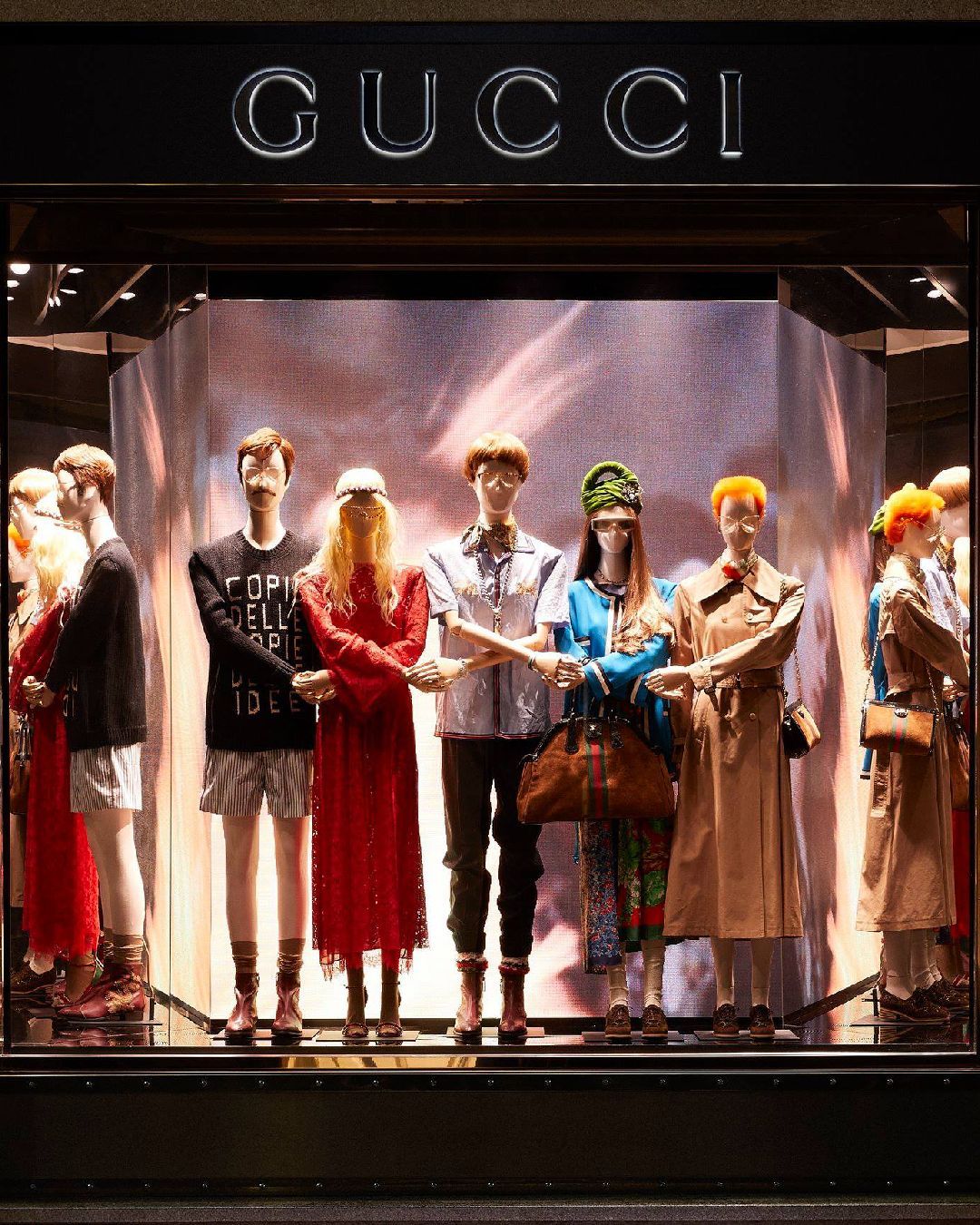

Greta Tafel, former WW Visual Merchandising Designer for Gucci, vividly remembers the maximalism of Alessandro Michele's tenure as creative director from 2015 to 2022. Recalling some of the most unusual windows she worked on, she mentions «that time we had to recreate a swimming pool» and another when she dressed «aliens, real works of art.» The days of expressive castings and collections now feel distant, as do those when mannequins told fantastical stories that captured the attention of passers-by. Those were the years when diversity was celebrated, and "distinctive" beauty became marketing’s best friend. From 2020 onward, after a period when fashion tentatively dipped its toes into the diversity trend—in 2017, a study found that 100% of high street shops in London had "underweight" mannequins, while two years later, Nike launched its first plus-size and para-athlete mannequins—brands halted the process of “resizing” their models. However, Tafel explains, this wasn’t a complete reversal but rather a kind of «flattening.»

«Generally, there’s now more of a shift toward minimalism, and the postures and attitudes of mannequins are much more standardised. I think they can be seen as a neutral mirror: seeing clothes on something so abstract and refined ensures you’re not influenced by the body, gaze, or hairstyle wearing it.» Moreover, by eliminating all cultural references, creative directors and luxury houses have managed to escape the grip of cancel culture that once held sway during the era of inclusive fashion. «Once, I had to consider '80s wigs for mannequins,» Tafel recalls, «but we encountered many issues—American colleagues warned us that any hairstyle vaguely reminiscent of Afro styles was highly discouraged and frowned upon.» Essentially, removing mannequins' "bodies," facial expressions, and even their hair has granted brands complete neutrality, both commercially and politically.

The theory behind the "political neutrality" of thin mannequins now appearing in shop windows worldwide also has a scientific basis. Given that the shape of a mannequin, like store interior design, can influence consumer purchasing trends, a study from the University of South Carolina found that people are more inclined to shop when surrounded by semi-realistic mannequins due to «a lack of distinguishing details that could introduce bias.» Although Gucci’s example shows how introducing cultural references in displays can expose brands to the risk of cultural appropriation, some brands in the past have proudly danced along the fine line between bad and good publicity. In 2015, American Apparel displayed mannequins with thick pubic hair in its New York windows—a look that sparked hate but also earned the brand new fans who appreciated the statement during a time when the U.S. was grappling with the misogynistic rhetoric of future President Donald Trump. This shows that, although for now the "political neutrality" of slim mannequins offers a safe haven for brands, the time will come to lift anchors, unfurl sails, and take risks again.

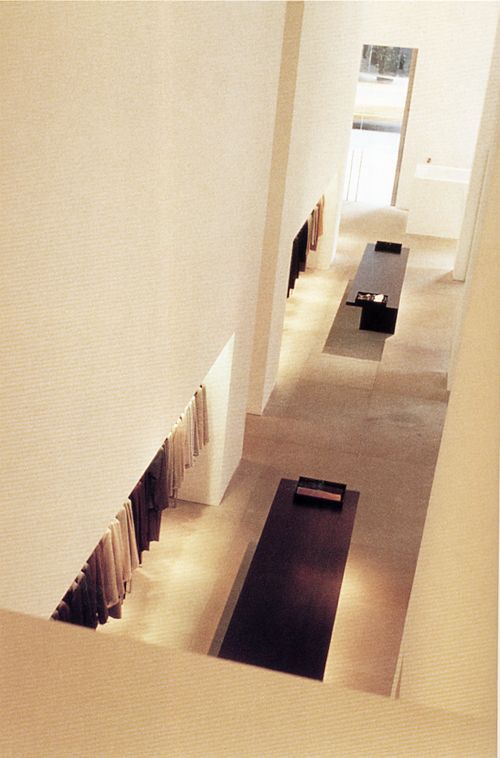

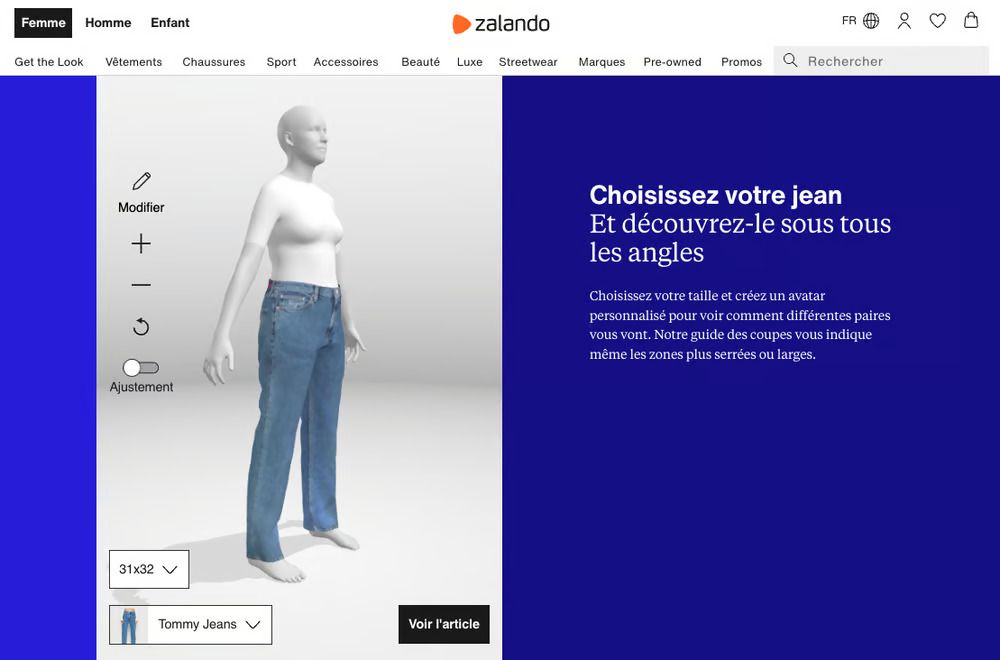

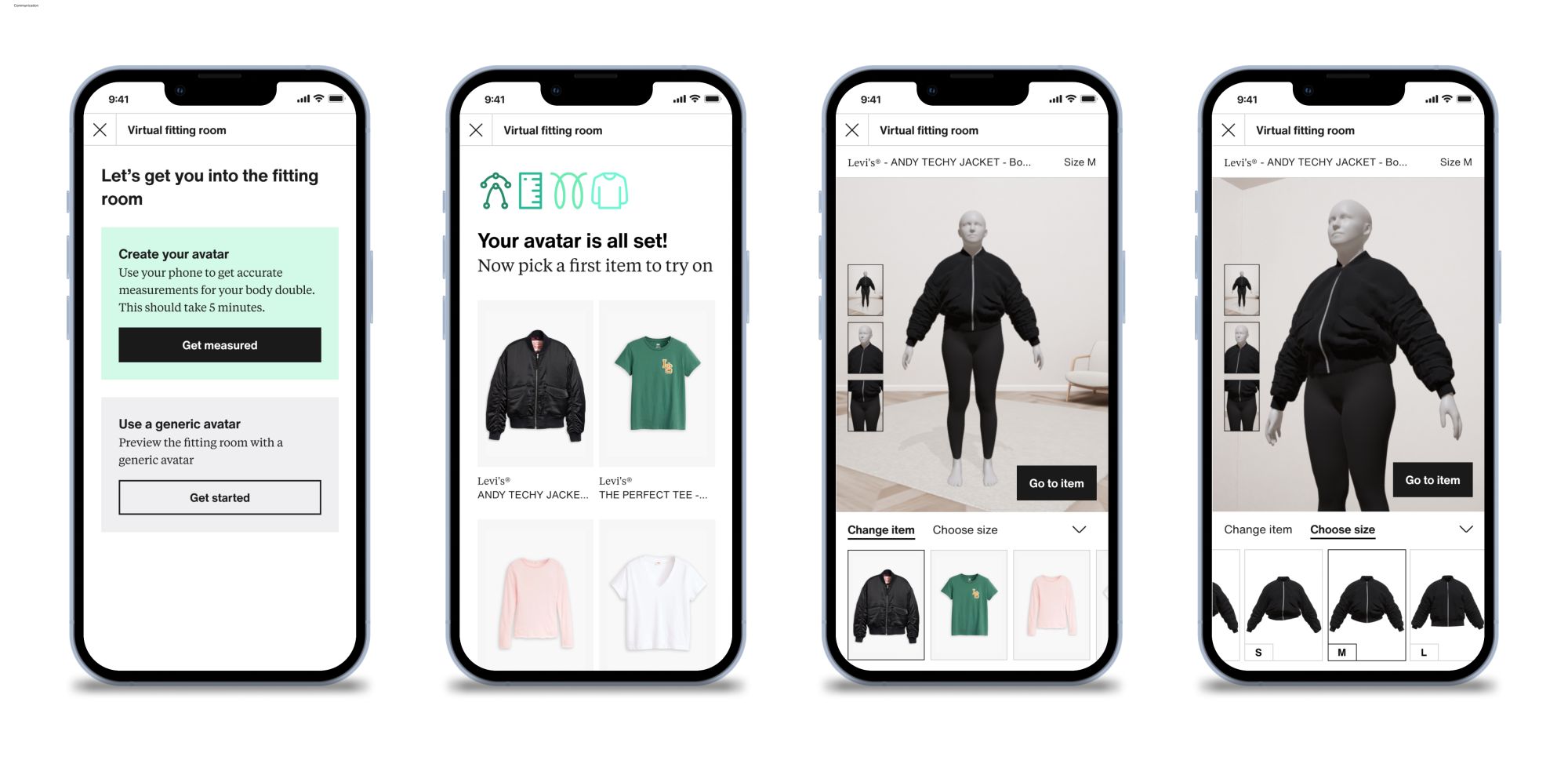

«I wouldn’t rule out a future where shop windows become LED screens with fake 3D projections, holograms, and who knows what else,» says Tafel, convinced that while mannequins are getting slimmer, they will never disappear. «It’s often more practical to hang clothes on racks or fold them for customers to touch or try on, but sometimes, with smaller collections, having a mannequin adds dynamism; it all depends on the brand’s strength,» she adds. A glimpse into the future of mannequins comes from Zalando, the e-commerce platform that recently launched virtual fitting rooms, where shoppers can view clothes on a mannequin with their exact measurements. Given the buzz around this new technology—spurred by a Zalando survey showing that fitting rooms cause anxiety and frustration—we might soon see mannequins in boutiques with our precise size. Only then, after years of diets consisting of quiet luxury and other prepackaged aesthetics, mannequins will finally have something tasteful on their plate: our personal style.