«I wasn't just making clothes, I was creating bodies» - Interview with Sébastien Meunier On Martin Margiela, Ann Demeulemeester, and especially himself

Dressing a body. This is the fundamental act underlying the operation of an industry that, in Italy alone, generates over 102 billion euros a year: dressing a body. And thus determining its perception, creating an entire narrative through a material medium, sometimes even a world, if we are willing to see it. This is how women discovered miniskirts, reclaiming their sexual liberation in the swinging '60s, and how men, with the same function, discovered the same garment 30 years later. But it all starts with the body, with how much we want to conceal or reveal, with the perception we want to evoke in others by dressing it one way or another. For Sébastien Meunier, this has been the case from the beginning, and it wasn’t just the body that had to be at the center of everything; it was his own body, in an obsessive quest that began during his university years, with the victory of his skinny punk boys at the Hyères Festival in 1998. From his role as head of menswear at Martin Margiela to the creative direction at Ann Demeulemeester, the French designer's work has taken on different nuances over the years, sometimes more subtle and romantic, crossing paths with Belgian fashion and its anonymous masters for over two decades. Today, that youthful obsession returns—because it never really went away—with his eponymous brand and a studio that draws inspiration from Arte Povera, from a work jumpsuit that can be assembled and disassembled at will, adorned with prints marking the key moments in Meunier's biography. "My work is much more sensual than it was with Ann and Martin," says the designer, speaking from the turquoise walls of his home-studio, behind him an imposing marble cross, a photograph of Marina Abramović and Ulay screaming at each other, and a rack of printed T-shirts. One reads "Holy Shit," another "A rose is a rose," and yet another features an image of a satyr, taken during a trip to Pompeii with Margiela himself ("It was then that I fell in love with Italy," he confesses). The conversation was abundant; attempting to summarize it is a necessary sin, but in that ever-changing atmosphere, surrounded by the memorabilia of a lifetime and the capsule collection marking a new chapter, Meunier revealed himself as a designer, a man, once again a boy, always in the most "instinctive way possible."

You spoke about the strongly autobiographical intent behind your eponymous brand. For years, you lent your vision to two maisons that made fashion history, perhaps blending your vision with that of an already established house. How does it feel to create a brand with absolute freedom?

I never really felt uncomfortable working for another brand and integrating their codes. But it's more interesting for me, at 50, to recreate my brand because I can return to a more personal way of working, talking about my experiences, my sexuality, my obsessions. In the past, I did this in a very generous, genuine way, without limiting myself. I performed, I presented a more androgynous man 25 years ago, presenting a way of thinking that didn’t yet exist in fashion. Today, I'm happy because my idea of man or woman has made its way into the system, but in these years, I’ve worked for other brands, perhaps expressing myself on the subject in a more conceptual way. My vision, however, is instinctive.

In a 2021 interview for Vogue Greece, you said, "I want my girls to protect my boys." That phrase stuck with me.

I've always seen the protective power of women and a greater fragility in men. I liked the idea that it was the girls who defended the boys I dressed, not the other way around. I can’t say for sure that my brand will go in that direction because it’s constantly evolving, but I do know that this time I don't want there to be differences between men's and women's clothing. But obviously, when you put a garment on a woman rather than a man, it doesn't have the same impact, it doesn't give the same feeling. In the end, each piece adapts to the person wearing it.

I sense a greater sense of "sexuality" in this project compared to the past.

My work is much more sexual than it was with Ann and Martin. I think Martin was aware of the sensual energy I could infuse into a garment, and he was happy that I started designing for him because he wanted to add a bit more sexuality to his world. And I think Ann also discovered this side of me over time. When I worked for her, there was always this tension that I tried to introduce into every piece. In the end, I pushed this aspect further, trying to do things I wouldn’t have done for myself, perhaps because it was too early or not the right time.

You said, "Martin liked my awareness of the body." An awareness that might be connected to the idea of performance, which is really important for the brand at this moment, from your passion for ballet, which extensively inspired your work at Ann Demeulemeester with Nijinsky, to your collaboration for gay propaganda with artist Slava Mogutin. Always different ways of understanding a body.

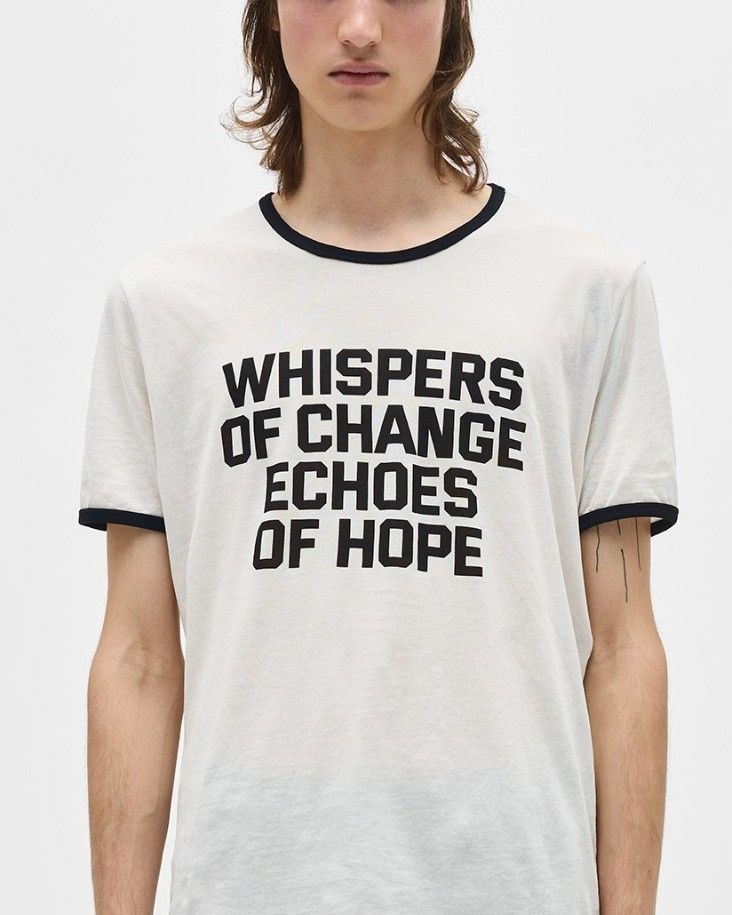

It all started with my first collection for the Hyères Festival. I had this obsession with the body, so I necessarily had to recreate one while making garments, almost conceptually. I wasn’t just making clothes; I was creating bodies. There were these skinny punk boys, covered in red and black leather, with well-defined muscles, conveying an almost pornographic tension. This was also reflected in the jewelry: I made many pieces inspired by bones. I was obsessed with the body, even with my own, in a way. Probably because I was young and exploring my sexuality. Today, through social media, people easily express their physicality. At that time, it wasn’t possible, so I had to sublimate this need through the models. But I also wanted to show myself, and I remember once deciding to model myself, dressing and undressing in front of the audience to showcase the entire collection. But then, after discussing it with the team, we realized it would take more than 20 minutes, too long for a show. In the end, I reduced the time to ten minutes, hiring two models and keeping the act of dressing and undressing. Later, I started exploring the concept of performance in fashion, collaborating with choreographers and artists, photographing and printing parts of my body on invitations and garments. I began to see fashion as a form of performance art.

You’ve mentioned obsession many times in this interview. I believe the most important creative minds of our century, or even of the world, are like that precisely because of obsession, in a sense. So, what are your obsessions?

It’s true, I think that a creative mind, in general, repeats something and repeats it in their own way because the life of a designer or an artist depends on it, in a sense. There’s this strong sense of urgency, and it’s this that makes it an obsession: because it’s a thought that constantly returns to your mind, an action you can’t help but do. By expressing this urgency, you can sometimes connect with other people and share something you couldn’t express in a conventional way. Maybe this is my language, my way of speaking, in a sense. Fashion is the only thing I really know how to do. My concerns translate into my garments.

I was thinking about the 2005 "Homme Sandwich" performance, where models represented different stylized characters, each with a paper bag over their head printed with your face in different guises. You yourself walked the show dressed as Superman: on your bag, it said "megalomaniac." You’ve talked about the idea of exposing your body as a creative necessity. A concept that seems at odds with the spirit of the brands you collaborated with for over twenty years, which built an entire narrative on anonymity. The dilemma has always been whether or not to expose oneself as a designer, but with the advent of social media, the issue seems to have become even more complicated, right?

It’s an interesting question because it touches on a topic that concerns me a lot. I’ve worked with people who prefer to remain anonymous, but I wanted to express myself first and foremost through my clothes, probably because I didn’t know how to express myself otherwise. After twenty years of working with this type of designer, I realized that I also enjoy working in the shadows, without seeking exposure like a star or an influencer. I just want to find myself through my clothes, like a writer who talks about themselves in their books. I feel very uncomfortable with social media, even though I find them both fascinating and dangerous at the same time. I think they should be a means of expression, but not an obligation to make oneself known. When I was young, this opportunity didn’t exist, and sometimes I’m a bit jealous of the young people today who can showcase themselves so easily. But perhaps if I had had this shortcut, I wouldn’t have felt the need to express myself through clothes. It’s important to have difficulties that force you to think more about what you do and make you stronger in what you express.

Can limiting oneself create new possibilities for one’s art?

I’ve always tried to impose restrictions on myself voluntarily, and I find a lot of inspiration in Arte Povera. I’ve always worked on prints without using the computer. Even today, I don’t use it much, except for emails. I’m very old-fashioned in this sense; I still work with photocopies, cutouts, manually reconstructing images. I only draw when necessary, not because I particularly enjoy it. I work with what I have available, often feeling uncomfortable with new technologies.

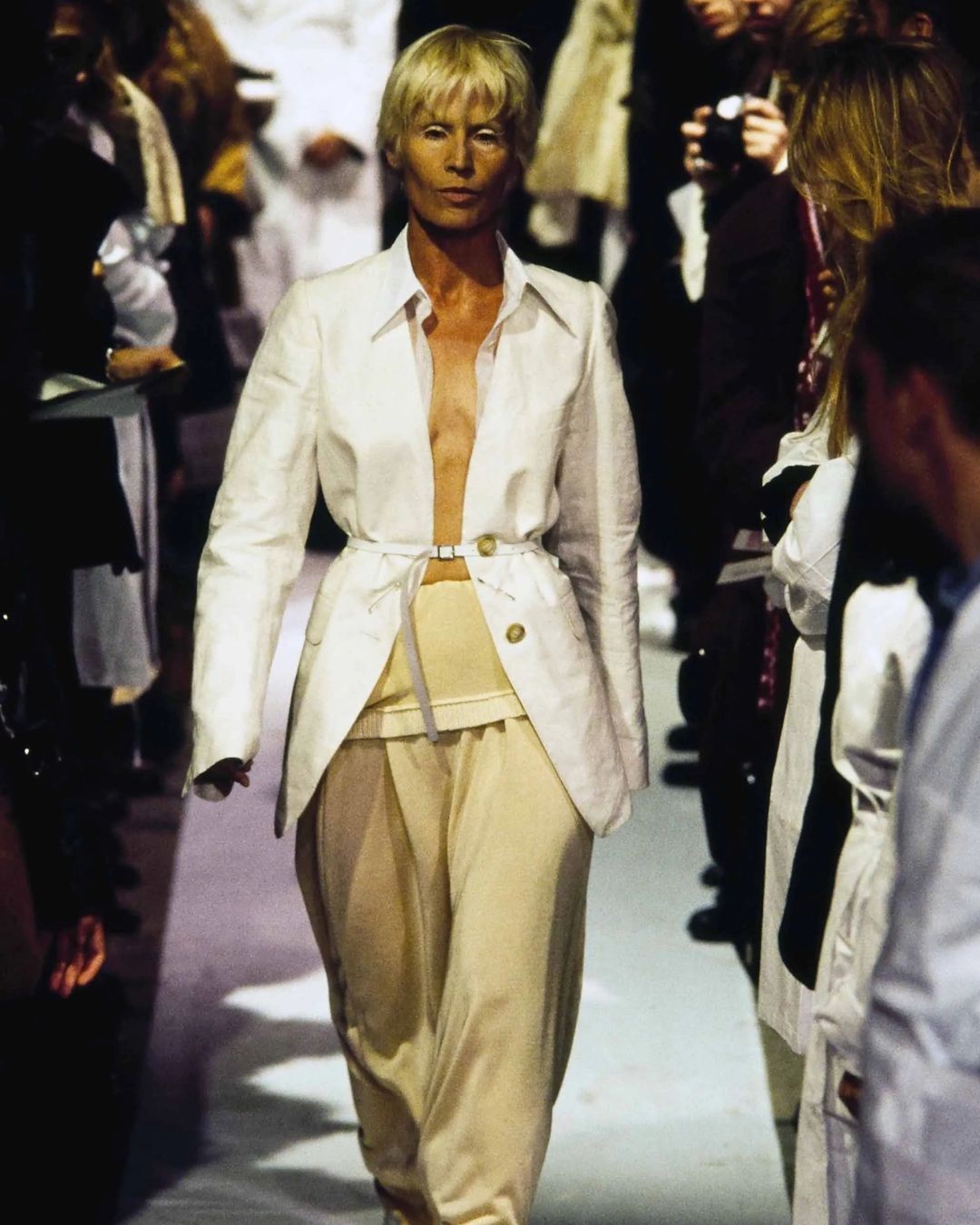

The last questions I want to ask you are a bit nostalgic. What is your dearest memory of Ann Demeulemeester and your collaboration?

When I met her for the first time, it was at Maison Guiette in Antwerp. We talked for hours, much longer than expected. We even went out to eat together—falafel at a kebab place in Antwerp—and in the end, they took me to the station. I was still on the train when Patrick Robyn, her husband, called me and said they wanted to work with me. She introduced me to PJ Harvey and Patti Smith, and the Le Corbusier house, a UNESCO World Heritage site, soon became my studio. It was the start of an incredible experience, a collaboration that lasted ten years.

And what about Martin Margiela?

Martin. My most cherished memory is working with him. I think he is the most generous person I’ve ever met in my career. During meetings, the team would gather around the table, and each of us would present our ideas for the season. He would naturally share his vision, but we also contributed what we had discovered during our research, without having a precise direction to follow. There was total freedom in expressing ourselves, and suddenly, everything took shape with everyone’s contribution. I never felt like he imposed a specific direction on us; rather, he encouraged us to freely express our creativity and to be fully aware of our sensibilities. With just a few words, he always managed to guide us in the right direction, the one he desired, of course, but there was a certain magic in the way he did it. I never had any difficulties working with him; he was always generous and free of tension, which is rare in the fashion world.

Managing Editor Maria Stanchieri

Editorial Coordinator Edoardo Lasala

Fotografo Vincent Migliore

Videomaker Giulio Pipolo