When Alexander McQueen was the creative director of Givenchy And respect was a matter of creativity

During his career, Alexander McQueen had more than one empire. An eponymous brand, whose aesthetic and narrative codes continue to be deeply tied to his unique experiences; a maison with a burdensome historical-cultural heritage, still fueling the expectations of the entire fashion system as we know it today; and the creative direction of Givenchy under the LVMH conglomerate headed by Monsieur Arnault. A role that, perhaps, should be more correctly defined as an adoption. These were the same years when, to provide a minimal historical context, Rei Kawakubo was showcasing the controversial collection “Body Meets Dress, Dress Meets Body”, Martin Margiela presented one of his most conceptual collections inspired by Stockman atelier mannequins, Nicolas Ghesquière took the reins of Balenciaga, and Marc Jacobs of Louis Vuitton.

@form.community Alexander McQueen Interview on Fashion Television (1997) In the captivating interview on Fashion Television by Jeanne Beker, Alexander McQueen reflects on the state of fashion following his Givenchy debut in 1997. Lee shares a thought-provoking perspective on the industry, stating that he does not see clothes as inherently important, viewing them simply as garments rather than objects of veneration. McQueen challenges the seriousness with which the fashion industry often regards clothing, emphasizing the need for a more balanced and nuanced approach tied to his sexuality and lived experience. Shop now at FORM.SPACE

original sound - FORM

It was 1996: McQueen had recently graduated from Central St Martins in London, the academy from which John Galliano also came, who was the creative director of Givenchy until that year. McQueen had already gained two work experiences, besides having already launched his brand in 1992. In 1986, after seeing a TV report about the lack of apprentices on Savile Row, he decided to approach the royal tailors directly and got a job; a few years later, he was in Milan, working as a pattern cutter for designer Romeo Gigli - «Alexander McQueen appeared before me one morning in Corso Como», recounts the Italian designer. «I took him under my wing. One day I had him make a man's jacket. I had him redo it 4 or 5 times. On the final fitting, I removed the lining and inside the garment, I found he had written in large black marker “Fuck you Romeo”» - He was 27 when he became the creative director of Givenchy. «Someone like him, coming from a working-class family, known for his crazy, iconoclastic creations, was chosen by one of the most prestigious Parisian maisons: all the English celebrated the event as if they had won the World Cup» recalls Ian Bonhôte, one of the directors of the documentary focused on the life of the designer released in 2020.

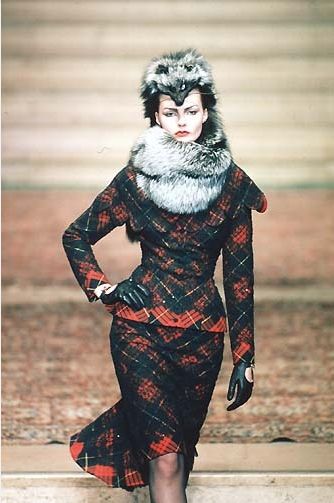

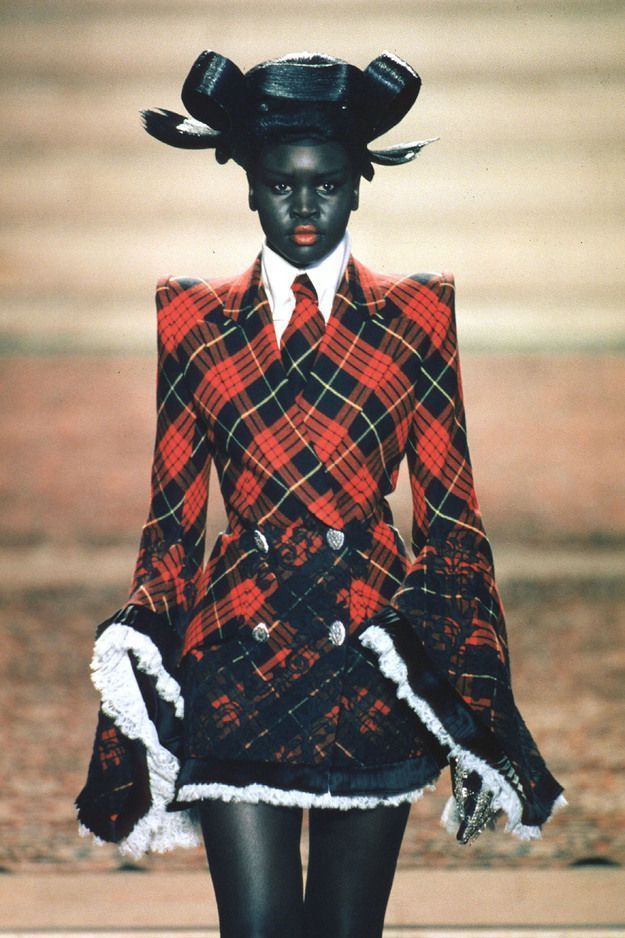

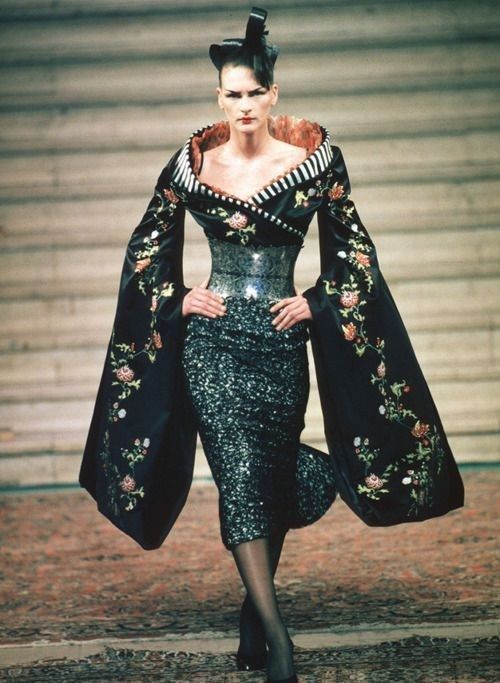

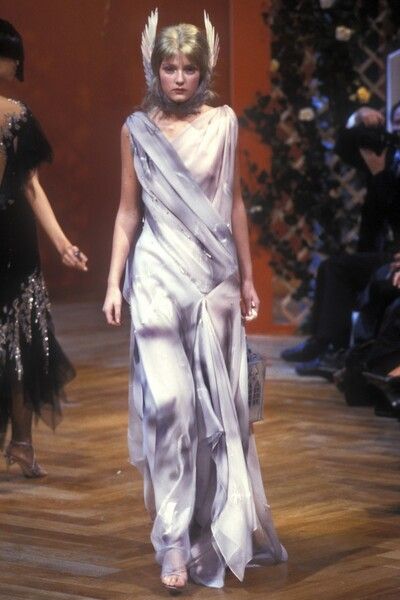

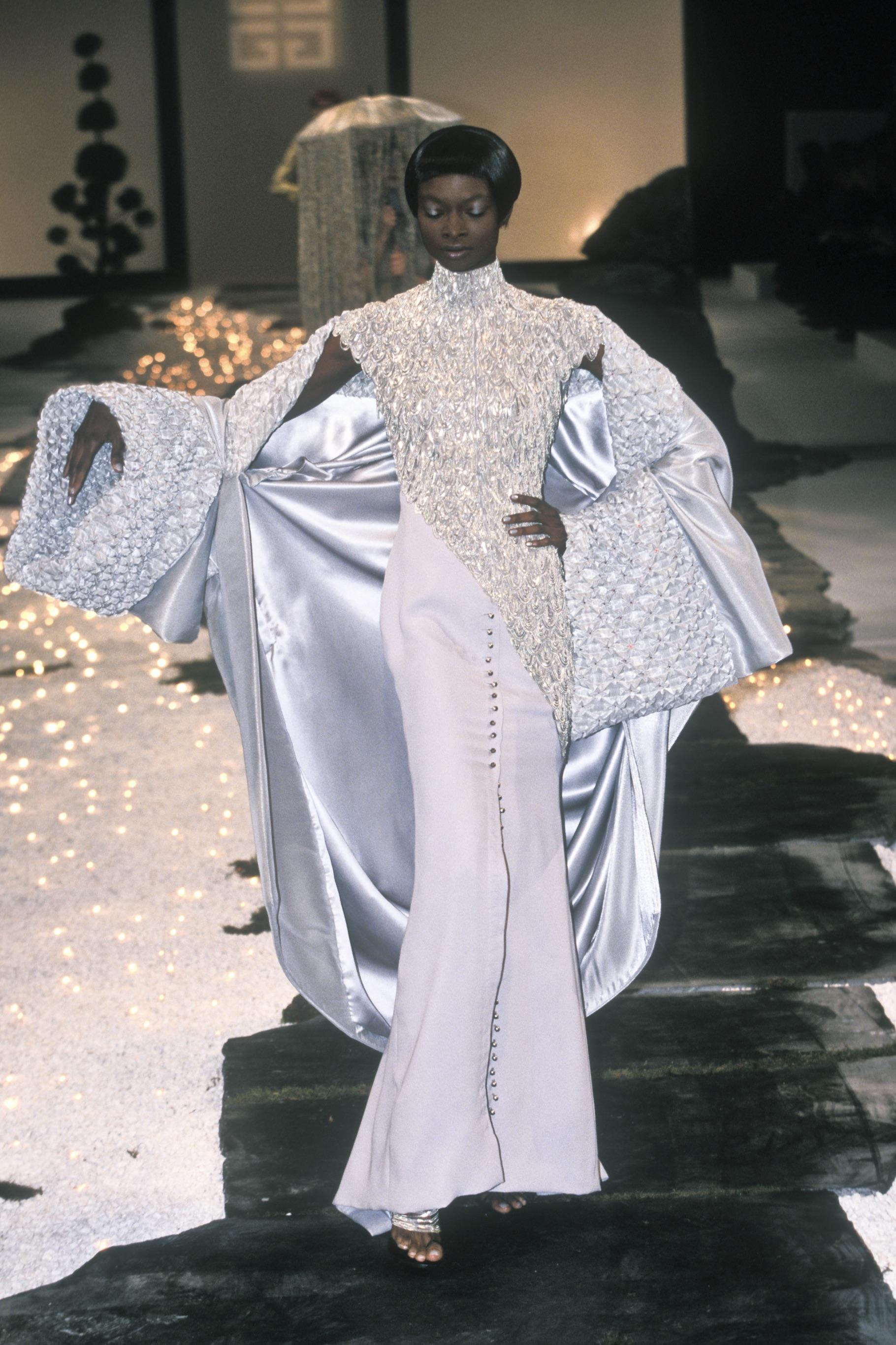

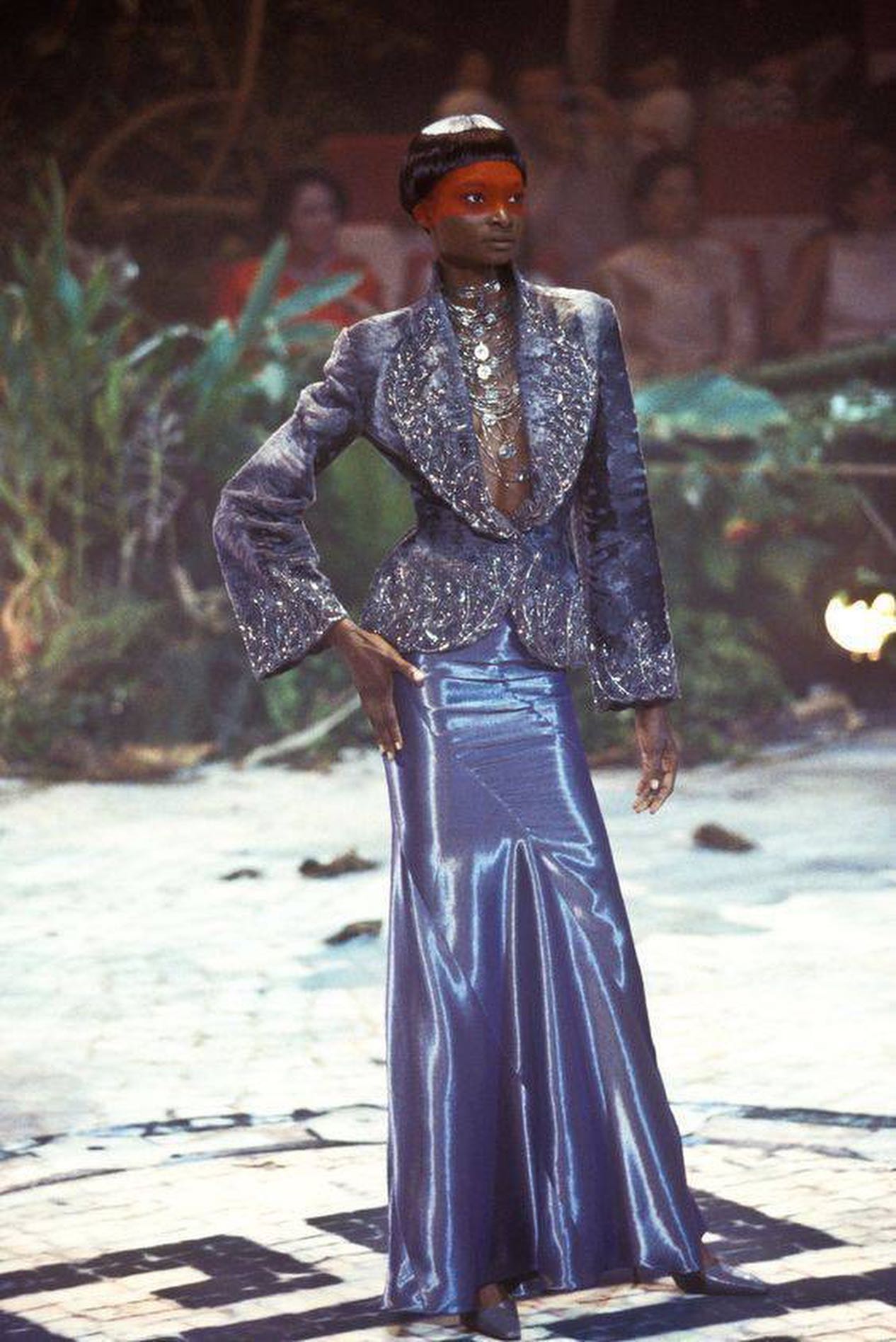

At Givenchy, the stakes were incredibly high. McQueen wanted to strip couture of its more stereotypical and glossy parts to bring it to a common ground for reflection without neglecting his aesthetic identity. «I am not intimidated by the exponents of Parisian haute couture. I am not afraid of them at all. I want to bring back that sophisticated ease that is unique to Givenchy, that’s what I want to do. Staying true to myself, without a doubt» the designer declared in some old interview retrieved from the web. The first collection he designed, within the philological work conducted by Vogue's editorial team, marks an unprecedented turning point. Condé Nast's flagship magazine speaks of "Couture Clash” alluding to both a generational and cultural clash centered on Avenue George V. Just over three months spent designing the first Couture collection for a luxury maison associated with well-rounded figures like Audrey Hepburn, ninety days to make something meaningful out of a fashion house's archive beloved by the press - the theatrical device, already adopted by Galliano, comes in the form of a reference to the myth of the Argonauts with The Quest for the Golden Fleece, McQueen's first show for Givenchy. White and gold, a tribute (or perhaps not) to the Maison’s Bettina blouse, Naomi Campbell adorned with a golden horned headdress, plastically winged corsetry to simulate the folds of a Hellenistic statue, dresses à la Maria Callas, Renaissance madonnas with capes matched with sheep horns (a couple came from Isabella Blow’s herd), ear cuffs bordering on the structure of masks and nose rings: for the press it was a «mess», for the premiere d’atelier Catherine Delondre «when we saw the pieces leaving the atelier, we thought, this is really couture». Setting aside his grunge plaid uniform, McQueen donned a pinstripe suit, perhaps to not excessively disturb the French clientele and press; as fashion critic Hilton Als reported in The New Yorker, the creative director clarified he did not want to dress Anne Bass «in bloodstained clothes….The reason I do it is because I am 27, not 57.» English fashion began to assert itself as a school of thought clashing against French standards. McQueen's first collection for Givenchy represents a historic shift, perhaps comparable to the work initiated by Charles Worth a century earlier.

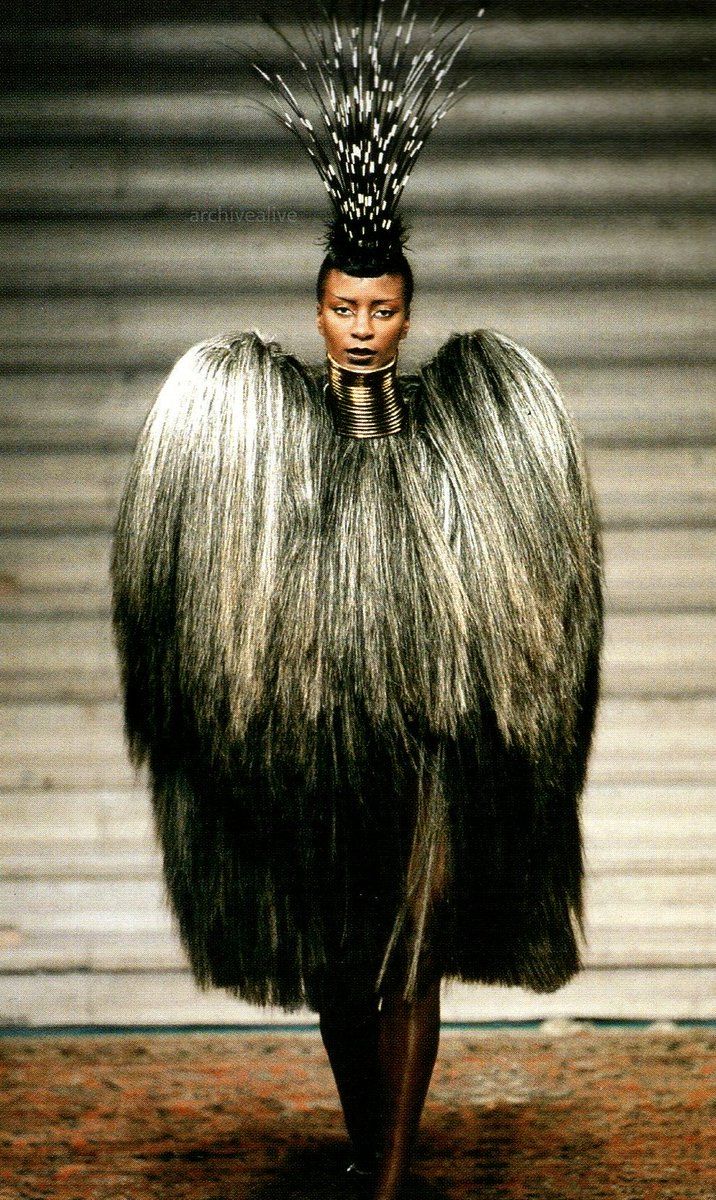

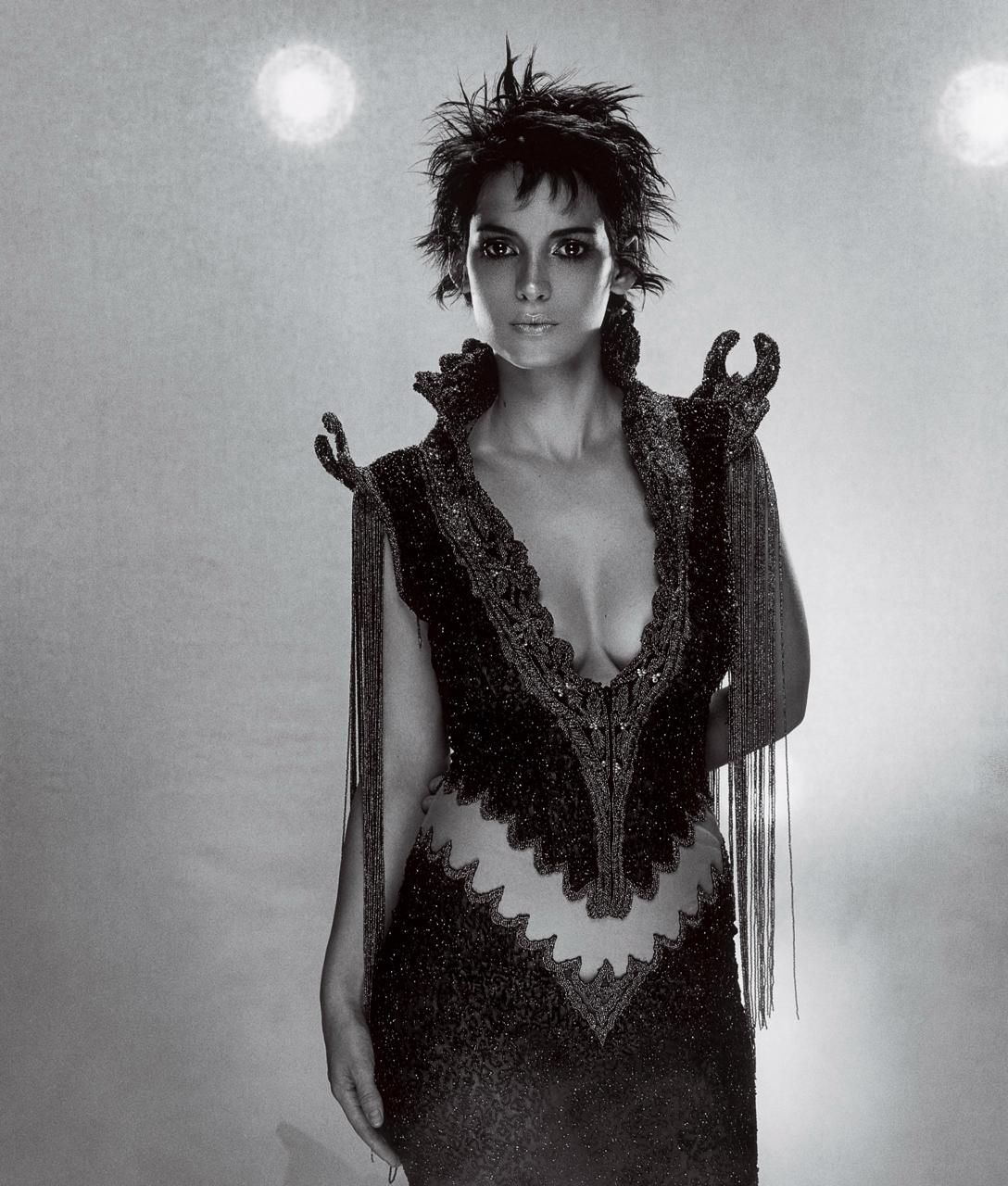

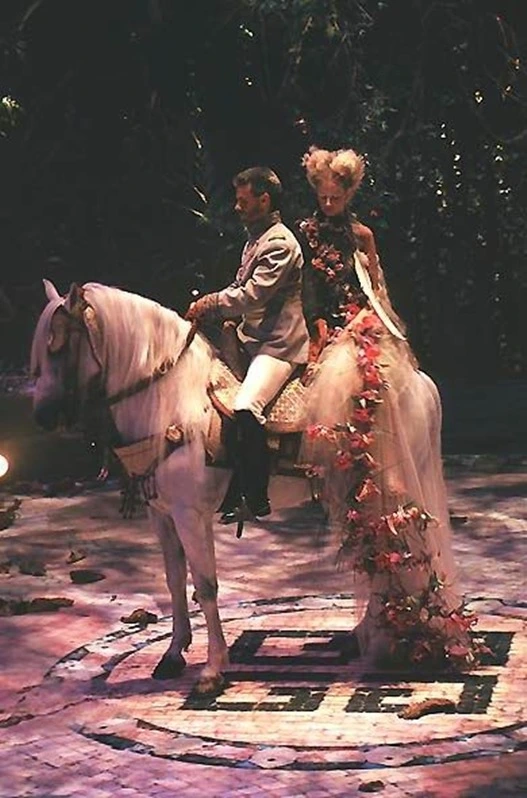

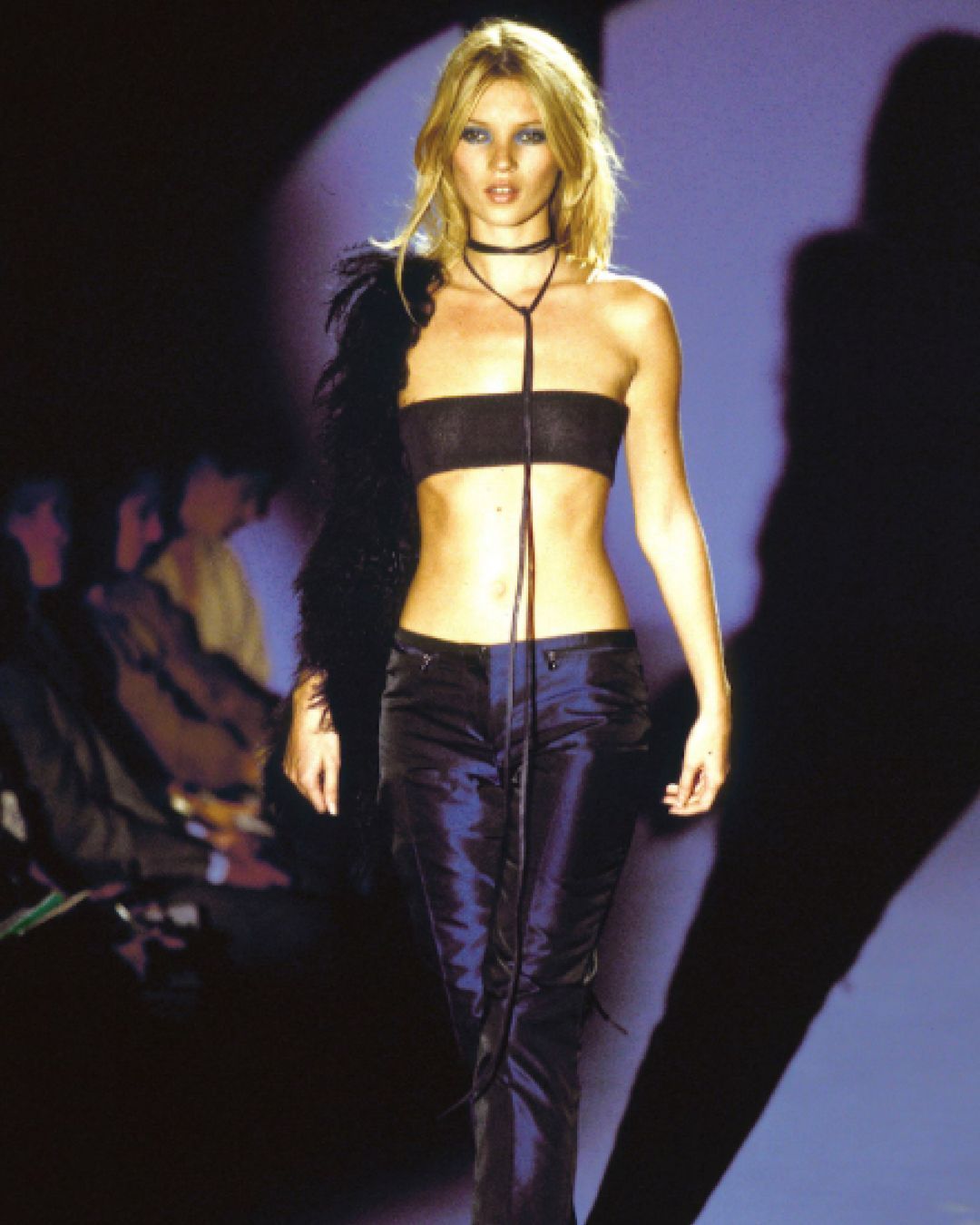

If with Couture McQueen's work managed to shock a generation of fashion editors attached to the front row who «would have been better off continuing to wear their black sunglasses» - as written in the essay The Artful Dodger by Ingrid Sischy - the ready-to-wear scenario was no different. The designer, who until now had never engaged with the world of haute couture, wanted to restore the realistic and commercial dimension of Couture by imagining addressing not only wealthy mothers but also their daughters. For this reason, he brought to the stage mountaineers, Asian princesses turned amazons, Dolly Parton fringes, the fragility of his aunt Patsy, cyber women or Blade Runner - his narrative anarchy sought to reconcile escapism typically associated with fashion with the constant gravity of reality, leaving no form of sugar-coating except in the viewer’s expectations. If with the FW97 Haute Couture collection, Eclect Dissect, McQueen had imagined the decadently triumphant resurrection of women previously killed by a sadistic surgeon, passing the baton to stuffed animals, geishas, Spanish lace, Burmese necklaces, and Eastern folk dresses decorated with feathers, with FW98 he closed the show with a lace bridal dress and pants (worthy of Queen Marie Antoinette) capable of synthesizing a temporal crasis between Rococo and 90s grunge.

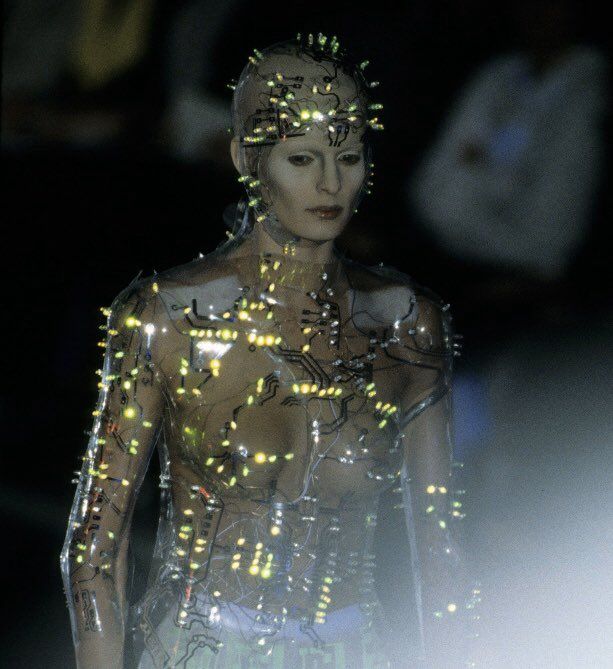

Moving to the field of prêt-à-porter, it is with the FW99 collection that McQueen gave shape and substance to what has gone down in history as “Cyborg Couture”: computerized Swarovski studs, microchip patterns, dresses made of circuits and LEDs in collaboration with Studio Van der Graaf fueled the batteries of the upcoming millennium. «It wasn’t a fashion show, it was performance art» as Vogue wrote about the SS99 Ready-to-Wear collection, etched in everyone's collective memory for the robot blitz that, armed with only paint, spattered the body of model Shalom Harlow helpless in a strapless broderie anglaise dress, cinched at the waist by a leather belt. In one of his last Couture collections for Givenchy, FW99, McQueen conceived a sort of art exhibition made of fiberglass mannequins illuminated only by spotlights - taking inspiration from a 19th-century painting by Paul Delaroche depicting the execution of Lady Jane Gray, a great-granddaughter of Henry VIII. In 2001, when the liaison came to an end, McQueen had already secured a commercial deal with the Gucci Group, which acquired a 51% majority stake in his brand. Thus, fashion’s hooligan could continue to love fashion in his own way.