Against nostalgia: interview with Michele Ciavarella «Without innovation there's no fashion», the journalist said

Now that, in 2024, the perceived serenity of the Western world seems increasingly at risk, amidst demagogies, wars, and the troubling culture of post-truth, it is natural for society to seek refuge where it usually goes when neither spirituality, art, nor even metaphysics offer comfort: the past. A lesson that many former branches of culture, now turned industries, have learned – making a transition that, especially in fashion, has transformed creatives into talent, creativity into content, and educators into media. It is precisely this transition that Michele Ciavarella set out to immortalize with his book Game Changers, in which he offers twelve personal stories of the main designers who have been the architects and protagonists of this shift. A book that is not a history but a window into the continuous state of flux in which fashion, whether it likes it or not, finds itself – a book from which the message emerges that the very notion of nostalgia should be avoided. And to better understand what the author thought, we went directly to ask him. «Nostalgia is a feeling that arises from the fear of change», Ciavarella explains to us, «and it works against innovation. But by doing so, it denies the very essence of fashion, which in itself is innovation. If there is no innovation, there is no fashion». However, nostalgia is not just an issue affecting fashion; it is more a general context in which individuals and societies find themselves immersed, scared by a present that, in becoming the future, reveals itself as unrecognizable. This resistance to change is the hallmark of what Ciavarella defines as «the nostalgic culture» of our days, which, far from concerning only fashion or even the creative world, also extends, for example, to the economy. «Markets are by their nature conservative and therefore nostalgic» since in economic logic, a winning horse should never be replaced. However, such an attitude blocks our path in the course of history: «Every time we notice resistance to change, we must ask ourselves if there is a problem of nostalgia: if we cannot detach ourselves from what we liked and therefore anchor ourselves to the past, then we are nostalgic because we are not willing, not to say accept the new and study it, but not even to observe it».

@nssmagazine @Michele Ciavarella recounts meeting Yves Saint Laurent: you can read this story and more in his book, "Game Changers: La moda tra due secoli”published by Politi Seganfreddo Edizioni. #fashiontiktok #tiktokfashion #fashiondesigner #creativedirector #storytime #storytelling #fashionstorytime #yvessaintlaurent Pieces of Redemption - Carlos Carty

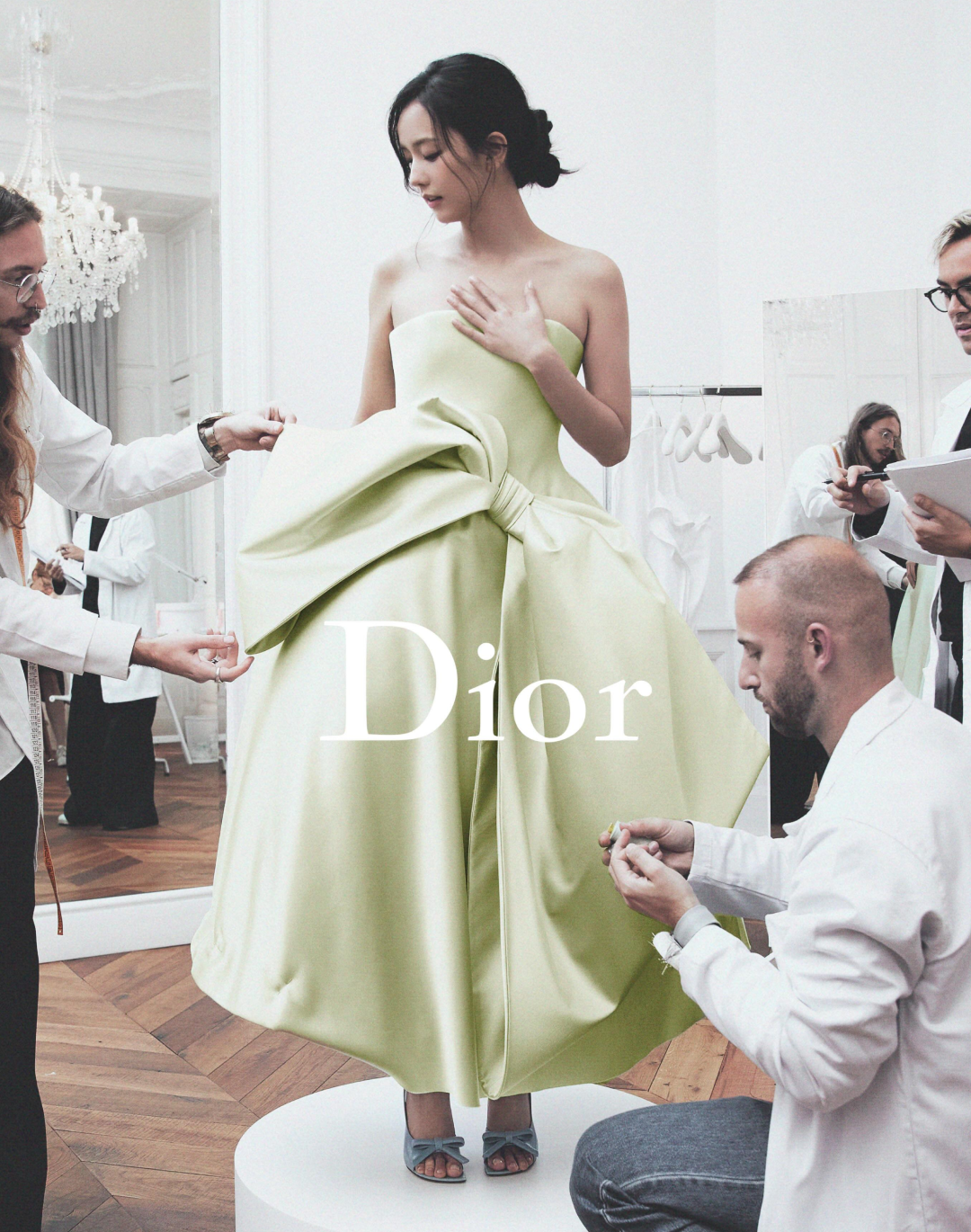

For Ciavarella, however, the problem has worsened in our times but did not originate now. «Perhaps fashion in the second half of the 20th century was born from a nostalgic feeling» he notes, reflecting for example on how even Dior's New Look, which in 1947 single-handedly revived the fortunes of French fashion «despite being contested by the right-thinking, brings the image of women a bit backward, with that torso hidden in the rigidity of the Bar jacket and that full skirt. In my opinion, it was precisely that skirt that gave the female figure a romantic and somewhat retro look, even exploited by mass advertising to portray the image of the “wife and mother” of all the 1950s». Perhaps a change was seen with Yves Saint Laurent, his revolutionary Rive Gauche, the concept of unisex and prêt-à-porter «but then already in the following decade, we started talking about revivals of previous ones... The entire 1980s, with Reaganite hedonism and baroque rock, were one citation after another even of recent years». It was the era of large acquisitions, in which today's luxury conglomerates arose, in which small artisanal ateliers became factories, in which human designers became de-branded brands that «nostalgia became a powerful narrative through the construction of the myth of archives and DNA». And the word Ciavarella uses, “myth”, is not accidental: «The archive should not serve to give continuity to a line or a shape or a volume. The archive is the historical memory in which many stories of a brand are preserved. Archives do not guard any DNA. One day someone will explain to us what the DNA of a fashion brand is and how fashion could survive the passage of time if it were bound by the chains of a DNA». And since we were previously discussing Dior, Ciavarella takes up his example: «Let's think about how many memories are kept in the Maison Dior archive: that of the founder plus those of Saint Laurent, Marc Bohan, Gianfranco Ferré, John Galliano, Raf Simons and now Maria Grazia Chiuri. Of which of these many memories should we be nostalgic?»

But here the problem becomes more complicated. The culture of fashion rests on two pillars: those who create and those who wear, the creator on one side and their audience on the other, the object and its spectator. In short, nostalgia is a double-edged sword – especially in a hyper-visual, hyper-fast civilization like ours, where all the past seems flattened on an indefinite backdrop. «The same nostalgia that today makes many, even the very young on social media, say that when the founders made fashion, it was better and which can be summed up in the phrase “the founder is turning in their grave”. Which is very stupid because no one knows what the founder would have done today. No one knows what that genius Yves Saint Laurent would have done today», explains Ciavarella. «To the new generations, everything can appear new. The same social networks often propose photos of past fashion», he continues. «There are many accounts called “Tribute to…” and in reality, they convey a retro sentiment that is a real trap for young people whose first approach to fashion comes from continuous and fast scrolling on a device screen. It is not wrong in itself to propose images from the past, it is wrong to propose them as better than those of the present». This creates a spiral of repetitiveness for those who make fashion and do not just observe it – as fashion is as much a creative as it is a commercial dimension. «Those who regulate and command the markets, like commercial departments and especially marketing, propose products in continuity with previous sales and consumers fall into this trap because having worn a dress that matched their need and image, they think of perpetuating it for convenience. Or also to avoid self-destabilization».

i feel bc of this reason fashion has become so repetitive and boring, overall. nobody is designing out of passion and love, just for sales, but i also think is a cultural problem, we pay more attention to bland looking celebs and tik tok starts, people who do nothing creative -

— vi (@mcqueenwitch) November 23, 2020

To better illustrate this contradiction, Ciavarella uses the image of roots: «Nostalgia corresponds to the roots that force plants to remain fixed in one place. People do not have roots but origins, and with those, they can move anywhere. Origins can be remembered and used to find new and unexpected solutions - they do not impede innovation. Thus, archives preserving memory or historical memories are the origins, not the roots». But what is, concretely, the risk of nostalgia? For Ciavarella, the evidence is before our eyes, specifically we can find it in the enormous emphasis given to the wearable product in the latest fashion seasons. «Just think about how many times the so-called “formal wear” has returned to the male wardrobe, that is, what was born from the bourgeois revolution, with more or less innovative names, from normcore to quiet luxury. […] And the female image? The re-editions of the ladylike look are countless... And it is no coincidence that among the many revivals there are more bourgeois looks than avant-garde ones». The result is that «most of the fashion promoted in stores around the world is conservative, therefore nostalgic. I hope that the future will be able to develop something new and non-nostalgic. But with the system in the hands of financial powers, I really see it as very difficult».

@vestico_ Alessandro Michele >>> #runway #fashion #gucci Reverse - Bgnzinho

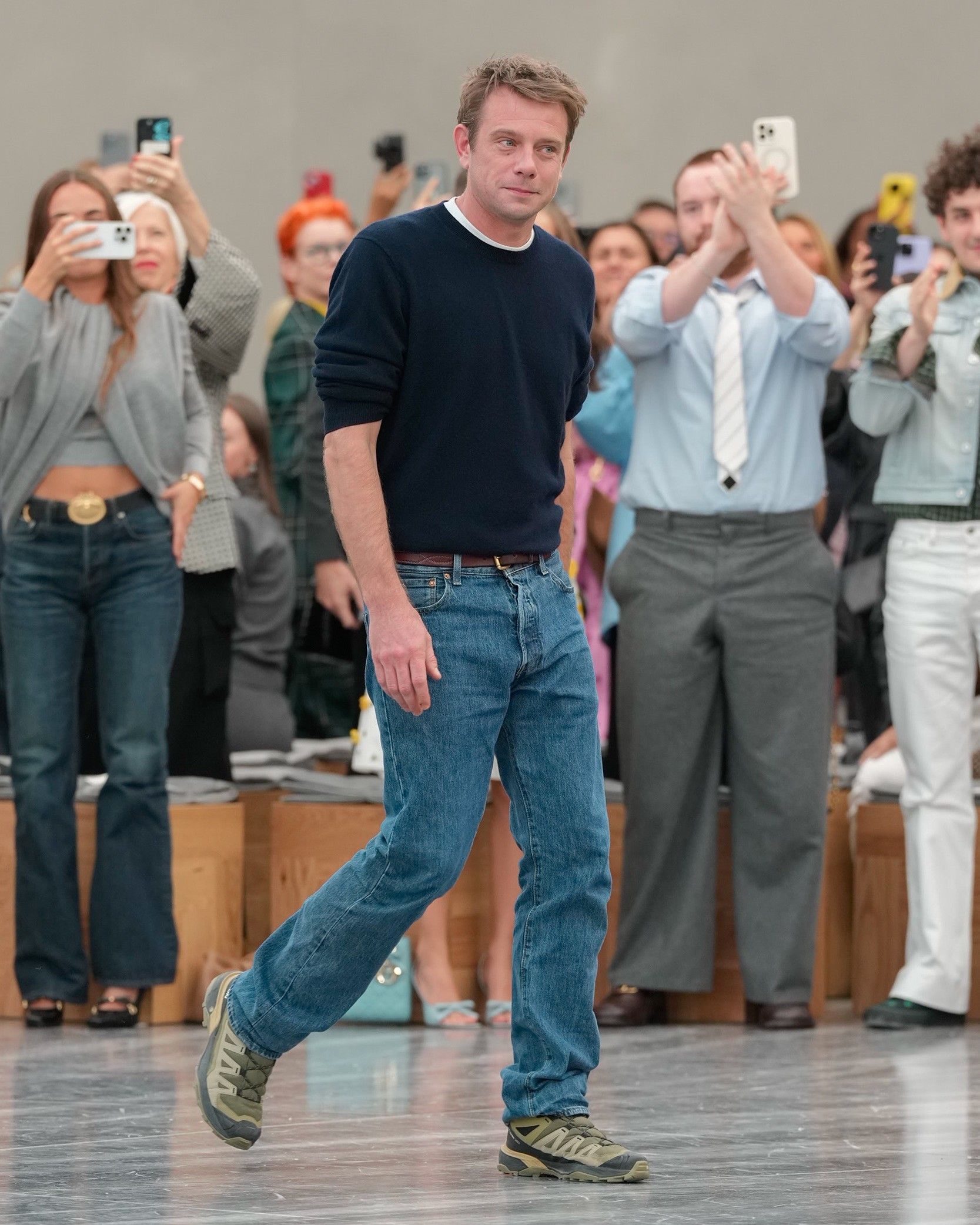

What is the antidote, then, to the tyranny of memories, to the «nostalgic feeling that clings with its harmful claws to many creativities»? After reiterating that «nostalgia is never healthy», Ciavarella pointed to a designer who has a healthy relationship with the past, and that is Alessandro Michele. A prophet of an eclectic style, lover of pastiche and contamination of styles, the creative director of Valentino «has made use of the past that is not at all nostalgic, on the contrary: he used it to build a present that conveyed themes that are still hindered today by regressive and nostalgic ideological parties». A past that, aestheticized, ceases to represent an old model of values and indeed, through the same technique of collage of styles and suggestions crossing epochs, styles, and destinations of use «has conveyed and brought genderless into the social debate to understand how the past can be used not as an engine that fuels nostalgia but as a tool to design an evolutionary idea of the present». Perhaps then there is an escape from nostalgia. Ciavarella concludes: «When historical memory works to produce the new, then the nostalgic feeling is defeated».