How fashion turned into merch From the end of subcultures to the hype culture aftermath

There was a time when merch was confined to the world of music, limited to groups of fans who loved wearing the albums of their favorite bands. The only message that a t-shirt with a band's name aimed to communicate was an individual's passion for that artist, the burning desire to show the world that on that tour date marked on their back they were actually there. There was a time when merch transformed into a luxury item, a status symbol for a few lucky ones. No longer an aesthetic manifestation capable of personifying a subculture in the form of clothing, it morphed into a golden ticket in the eyes of those those who, in front of their favorite artist, do not sing at the top of their lungs but pull out Instagram to take a story. Although it may seem that the value of the original merch (recnognised by concerts and fans) is different from the current one (governed by brands and drops), both have always traveled the same wavelength: the scarcity factor, popularised in the fashion world first by streetwear titans like Supreme, then by luxury giants like Louis Vuitton. After all, in the world of Hype Culture, the same rule as the concert industry applies: first come, first served, and so on. In the early 2000s, Supreme forever revolutionised the way we see merch, although it didn't know it would also forever change the way we sell it.

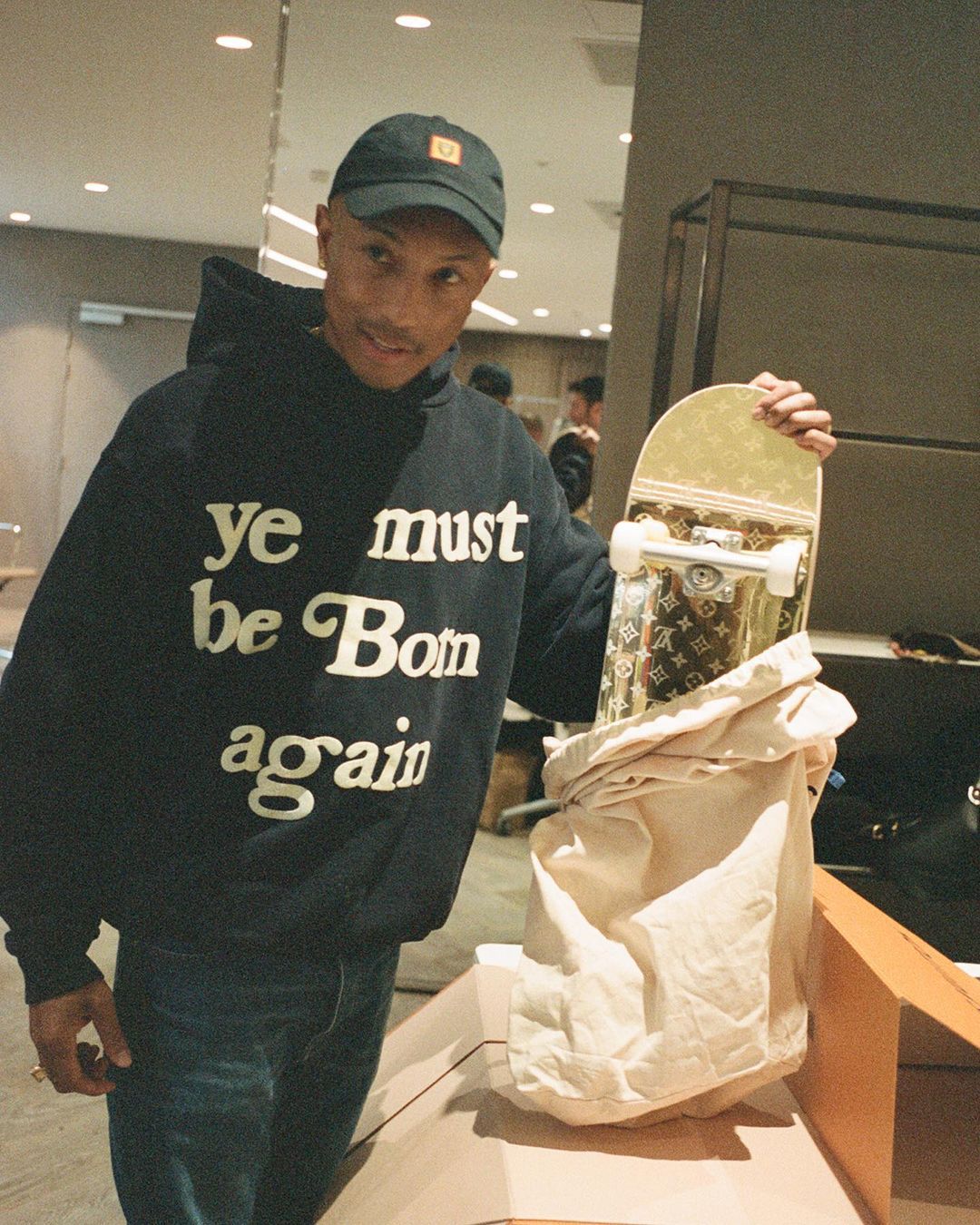

In 2021, Highsnobiety called the culture of merch as the only true star of the fashion industry “MerchTainment,” a force that today seems to have managed to encompass everything, even historic it-bags like the Louis Vuitton Speedy. In “Everything is Merch,” Ana Andjelic and Eugene Rabkin describe the Millionaire made by Pharrell for his first show as the creative director of Louis Vuitton Men as the ultimate exemplary stage of the transformation of fashion into merch. «The need to signal one’s goods has not disappeared, but rather, in the world of social media, it has increased,» write Andjelic and Rabkin. Offering examples that range from Nike Jordans to Balenciaga potato chip bags, they argue that «everything can be turned into merch if it is infused with enough symbolic value and cultural capital» and that it can be divided into the following categories: toys, puns, simulation, fantasy, winks, kitsch, and camp. In a drastic categorical subdivision that manages to differentiate JW Anderson’s pigeon bag from the same brand’s asparagus bag (the former is a toy, the latter is a pun), fashion thus becomes reducible to an object capable of projecting the wearer into the middle of a community that speaks the same language, without the need to go to any concert. And to think that we once believed fashion could free us from conformism in the name of self-expression.

Amid all the negativity brewing among those writing about the “end of merch” - some blame luxury, some blame cinema, some blame restaurants, and some blame the entire sector together - a question arises: why, if the essence of the concept of merch lies in its value of rarity, do we feel that brand merch is less authentic than the merch “of the past”? As often happens when searching for the reason behind a phenomenon influencing the fashion world, the answer must be sought in the streets where it was born. In Supreme stores, at the dawn of the revolutionary Hype Culture, among the customers jostling to get their hands on those logoed shirts were not multi-millionaire rappers, owners of private jets and entourages. Of course, there were some famous artists, but they came later: the first clients were the kids, the skaters, and the artist communities hanging around the store. Even earlier, the popularity of Nirvana t-shirts did not arise because some model wore it at Coachella in 2016, but because twenty years earlier, obtaining that shirt meant pushing and shoving - and perhaps even more - with some other fan of the band at the end of the concert. What makes an ordinary t-shirt an icon is not a cute graphic or a celebrity photographed wearing it, but the underground story of how it was born. Which is why, despite all the likes and views it may get, it's still hard for a maison selling bags for a million euros to make us believe that its logo is the coolest in the world. The best merch will always be the one that is sweaty and wrinkled, torn from another fan's hands at the end of a concert, not the freshly ironed and brand new shirt that the sales assistant has folded in eight pounds of embroidered paper.