The darkest hour for indie fashion Limited for now to the UK, disaster can be averted

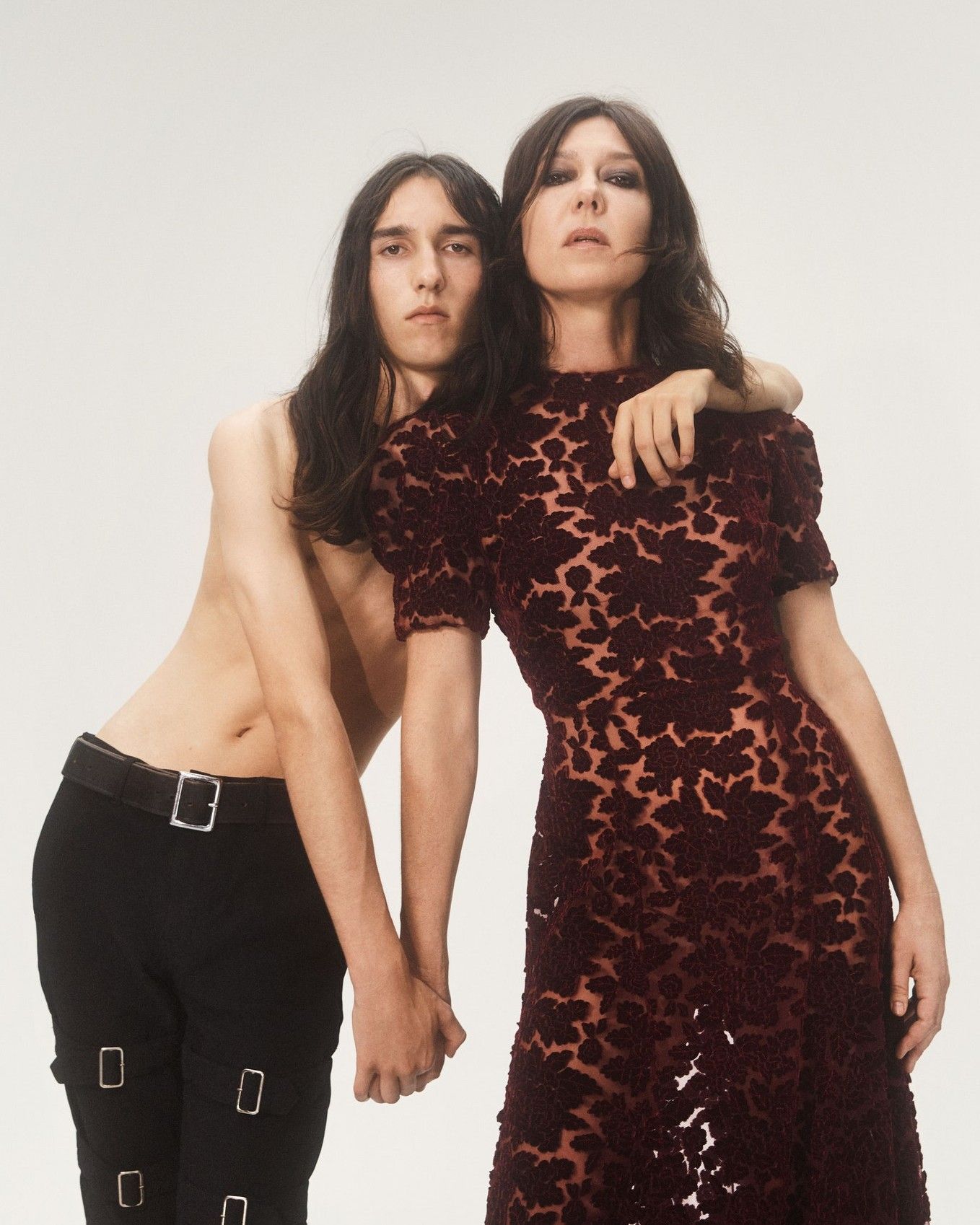

In English, catastrophes and natural disasters are often referred to with the somewhat fatalistic term “acts of God.” But while it’s debatable whether gods from this or that pantheon spend time sending hail and hurricanes to earth, what is happening to independent fashion brands these days indeed seems like the beginning of the end. Randomly: Dion Lee calls in administrators to manage insolvencies that already seem terminal, Roksanda gets bought out to avoid bankruptcy, Calvin Luo announces the gradual closure of his brand to be finalized by the end of the year, while Mara Hoffman and especially The Vampire’s Wife announce their closure outright. Not to mention how two other young cult brands, Puppets & Puppets and Mia Vesper, have decided to abandon runway shows and fashion week entirely to focus on handbags and jewelry respectively. If it is usually said that one clue is a clue, two clues are a coincidence, and three clues are proof, this week has given us irrefutable evidence that independent brands worldwide are literally fighting for their lives. And in times when even industry titans, LVMH and Kering, are suffering significantly due to the collapse of consumer spending, market saturation, and the financial collapse of major e-commerce platforms, it can be expected that, miracles aside, the situation will not improve.

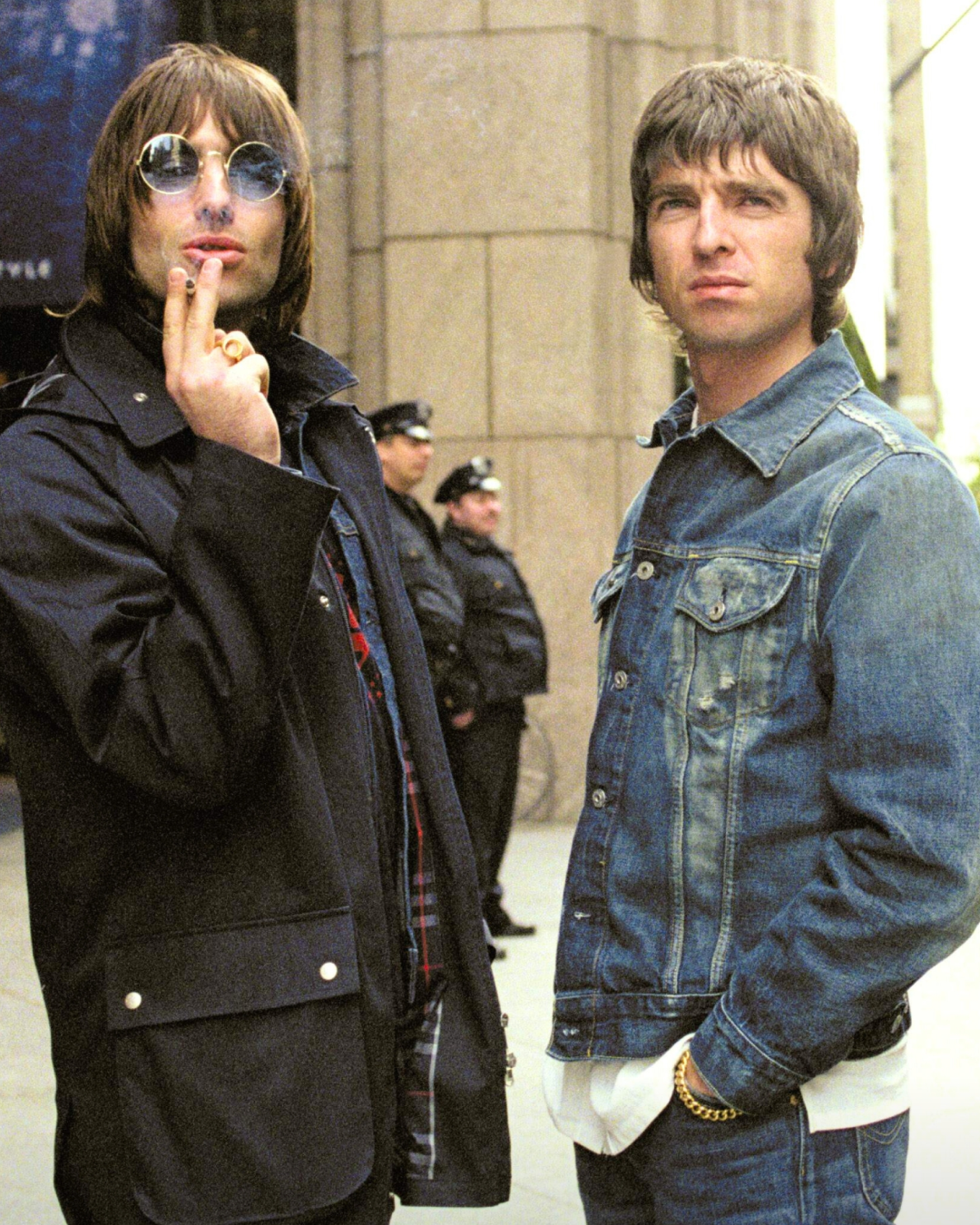

At the moment, the epicenter of the crisis appears to be London, where the disastrous implosion of Matchesfashion has created a void of unpayable debts towards brands that, moreover, cannot even get their hands back on their unsold stock. To clarify the situation, Matchesfashion owes half a million pounds to Burberry, one hundred thousand to Paul Smith, seventy thousand to the small jewelry brand Alighieri... the list continues with several brands that have been dragged down by the vortex of dying e-commerce platforms. These brands, in fact, relied almost entirely on these multi-brand e-commerce platforms for their distribution without having an independent distribution network as a backup resource. And this year, multi-brand retailers like Matchesfashion, Farfetch, Yoox Net-a-Porter have seen their businesses crumble: they were models that didn’t always function properly, inflated by parallel market trades, plagued by continuous returns from the public, and by out-of-control discounting that displeased both brands and individual retailers. Even in Italy, recently, the multi-brand retailer Modes filed for admission to the “reserved” arrangement procedure to manage insolvencies. To return to the UK, however, fashion has been severely penalized: besides the economic problems caused by Brexit, which impacted household spending power, the abolition of tax-free shopping for tourists four years ago has heavily penalized retailers as many tourists and residents prefer to shop on the continent. Faced with the death of brands and commercial difficulties, a group of names associated with London fashion has emigrated to Italy for this season: Martin Rose, David Koma, and Dunhill will organize their shows in Milan, while Paul Smith will do so in Florence.

This generalized “famine” was foreshadowed last year with the closure of Christopher Kane and, for some, predicts even greater disasters. «Fashion is an ecosystem, there is always a chain reaction», said Olya Kuryshchuk, founder of 1Granary, to The Guardian. Meanwhile, Sarah Mower of Vogue wrote that «what’s happened at Matches isn’t something that can be seen in isolation. It feels like a bellwether for what’s happening across the industry». Also on Vogue, Sarah Schultz says that «Matches is a symptom, not the root cause. That the collapse of a single retailer could cripple so many businesses signals that there was not enough industry support to begin with». But perhaps here lies the first conceptual problem: several articles from authoritative publications call for further government assistance which, according to them, should take care of an industry that brings 60 billion pounds annually to the UK's GDP. Indeed, taxes are the main burden on small businesses, along with online advertising expenses and the multiplied costs of having to follow two logistical operations at home and in Europe. But if the problem is the unsustainability of a business or a business system, why think that the government can solve every problem by reaching into its metaphorical wallet? Government foresight and economic subsidies are only a palliative, a temporary measure while independent brands (and the entire fashion industry) seem currently trapped in a Malthusian trap.

too many fashion brands, not enough sauce

— ROD (@iimrod) June 2, 2023

The concept of a “Malthusian trap” indicates a situation where the population of a certain area grows more rapidly than the availability of necessary life resources. To shift the concept to the fashion industry, very simply, on the market there are more brands than the clientele can reasonably support with their purchases. So far, the bubble had remained more or less intact, but now, with inflation and rising living costs worldwide, it has burst. Which shifts the problem to accessibility: The Vampire’s Wife’s final sale attracted many people to London, demonstrating that there is a clientele for the clothes if, simply, they cost less. It is no coincidence that sample sales are being stormed these days. In the case of The Vampire’s Wife, for example, the Falconetti dress, the brand’s most iconic model, is priced between 1500 and 2000 euros. Little compared to luxury brand prices that now demand increasingly obscenely high amounts for their products, but still an unattainable figure even for a middle-high income professional who would have to give up half of their salary to buy one. It is clear that there are production costs for ethical work that make quality clothes expensive – nonetheless, if the final product is too expensive, people won’t buy it. The problem, in short, could be identified in the fact that the clientele exists but is willing to spend a third of what many fashion brands, both indie and not, demand. All the more so as the market is overflowing with brands that often those outside the fashion week bubble are not even known.

@andreacheong_ I think the fit is lovely and i like that they have a core offering and its not always newness. But for the price… not worth it IMO #vampireswife #mindfulmondaymethod #howtoshopsustainably #blacktiedress #katemiddletonstyle #howtolookexpensive #sustainablefashiontips #shoppingtiktok original sound - Andrea

Targeting only the rich (a 1500 euro dress and a 1000 euro shirt are for the rich) greatly limits one’s clientele and therefore one’s cash flow: even a high-income individual may forgo a purchase if they see a four-digit price tag on a simple shirt. Meanwhile, the potential customers of that dress go elsewhere. To Elisabetta Franchi, for example, since her dresses cost half as much – so much so that Marco Bizzarri, an expert entrepreneur in sector dynamics, has invested in her brand, almost a symbol of the mid-market in Italy, becoming its president surely predicting its future growth. It is here that with all certainty the gold vein hides, it is here that large masses of customers too savvy to buy fast fashion but too poor for Monte Napoleone are already gathering with wallets in hand. After all, one cannot live on vintage and secondhand alone. It’s just a shame for all those brands that, obsessed with the quarterly chase for market repositioning, wanted to climb the luxury Olympus only to discover that there isn’t enough room for everyone at the top of the mountain.