How to become a fashion curator Interview with Valerie Steele

In the documentary Catwalk (1994), which follows the model Christy Turlington throughout a Fashion Month, when André Leon Talley is asked whether fashion is art, the journalist responds bluntly: «Absolutely not. Fashion is hard work, it's not glamorous.» The debate over whether clothing can be considered worthy of being displayed in a museum for admiration has polarised art historians for decades. However, today, the public at large recognises the true artistic value in the most majestic creations preserved in costume and fashion museums or even in the archives of collectors, to the extent that spaces like the V&A in London, which holds the world's largest fashion collection, and the MET in New York are packed with a real sense of «hunger for fashion.» This is how Valerie Steele, a pioneer in the study of costume history, curator, and director of the Museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology, describes it, who throughout her career has observed and influenced the changes in the role of the fashion curator. While entering the field may already seem like a complicated challenge, becoming a fashion curator is even more daunting for those without the right connections or support, compounded by both the exclusivity of the art world and that which the fashion industry tries to maintain. To the question "How does one become a fashion curator?" Valerie Steele responds, in summary, that it is hard work.

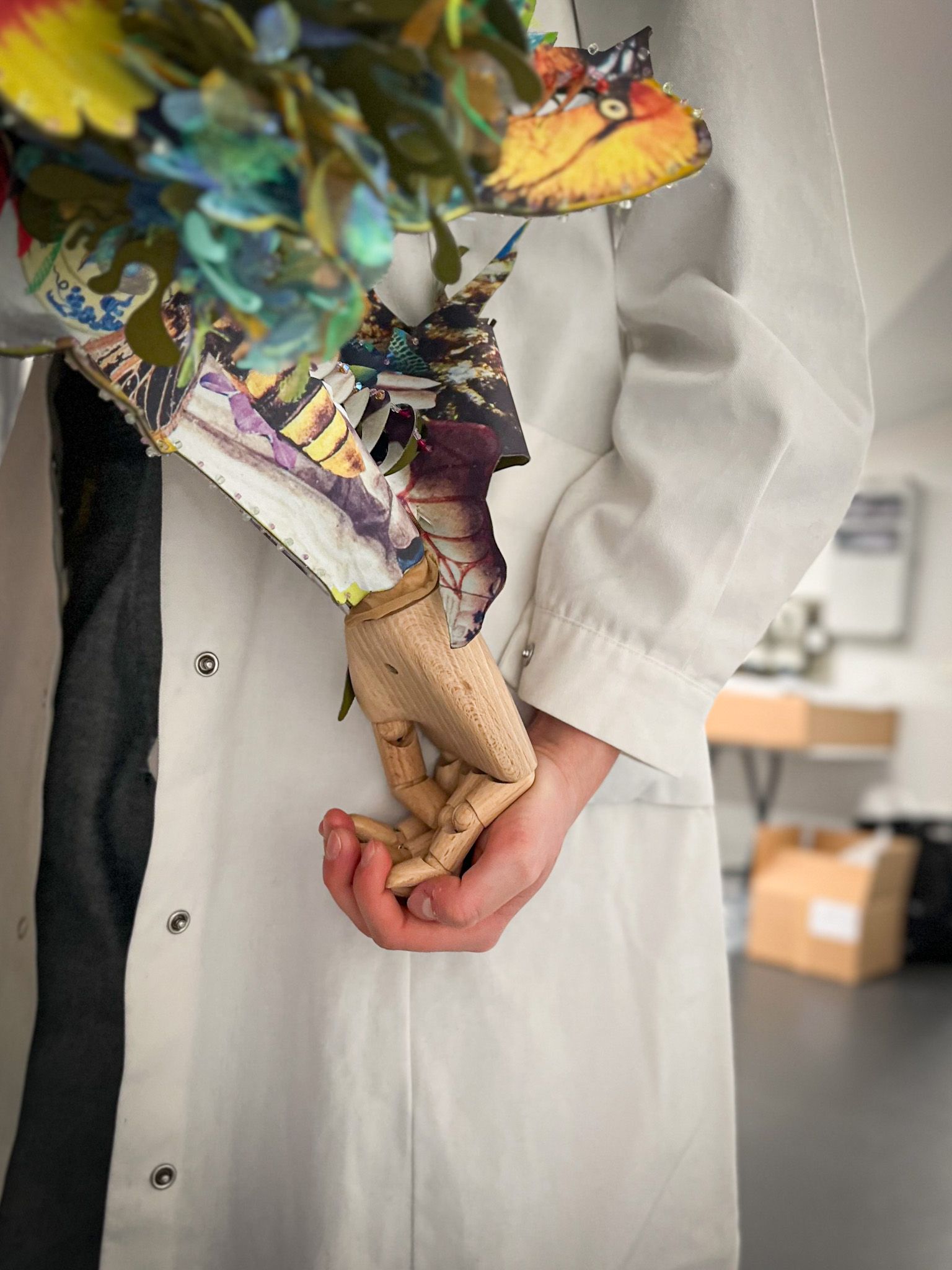

We met the historian in Trieste, on the occasion of the awards ceremony of the ITS Contest. A competition born to support the new promises of fashion, the ITS Arcademy project has been supporting emerging creatives for over twenty years, showing their works in a permanent exhibition. As Steele explains, including contemporary costume in museology allows us to observe clothing from a new perspective. «Exhibition spaces provide a very special kind of way to look at fashion,» she adds. «We normally look at fashion either with people sitting across from someone, on our little screen or in a store. When we see things in a museum space, you get a chance to look at it through a more aesthetic lens and as an object in society.» But the importance of fashion curation doesn't stop at anthropology: for Steele, museum work has the task of educating as well as «inspiring designers and people to imagine,» the main goal that anyone dreaming of curating an exhibition should pursue. «Everyone can identify with fashion,» Steele adds. «It helps the industry, but it also helps the wider culture appreciate how fashion is a creative art.»

Although, compared to London or New York, Italy seems to lag behind in the field of fashion curation, it is simply fragmented. Being unified very late, notes Steele, the distribution of creative hubs, and consequently exhibition spaces, is much more scattered among various cities like Milan, Florence, Rome, and many others. Museums of fashion are not lacking in Italy, such as the Ferragamo Museum, the Museo dell’Archivio Gucci o Armani Silos, but there is a tendency to isolate the history of brands when there is an opportunity to tell them in juxtaposition. As Steele recounts, one has influenced the other over the course of costume evolution. «I think designer exhibitions are beautiful and also serve an important purpose,» Steele explains. «But I think it's nice when you can have comparative exhibitions where you look thematically, not just at one designer.» This is where the curator's profession comes into play, which must be able to explore a theme and present it in an inquisitive manner, to represent a narrative that elicits questions beyond wonder. Using the example of Judith Clark, a curator capable of turning a few cubic meters into a narrative loaded with critical thoughts, Steele explains that creating a great exhibition requires experimenting with what you have. «I find that some of the most creative things happen when you take two different fields and smash them together,» Steele tells us. «The best fashion exhibitions have a really good idea.» Among the advice that Valerie Steele would impart to a young creative aspiring to become a fashion curator are simple rules, but ones that require discipline and dedication. «People have to be very, very self-directed because this is an extremely competitive field,» states the curator, lamenting the problematic nature of unpaid internships that unfortunately newcomers often have to endure before being appreciated by a potential employer. «The curator is just one face,» she adds. «There are educators, conservators, exhibition makers, media officers; it's like making a film, you have to try to understand not only what you like to do, but also what you're good at and what makes you stand out.»

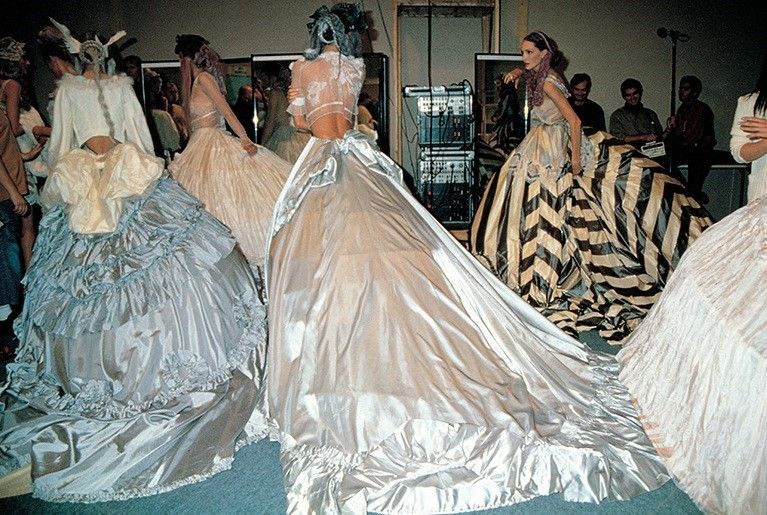

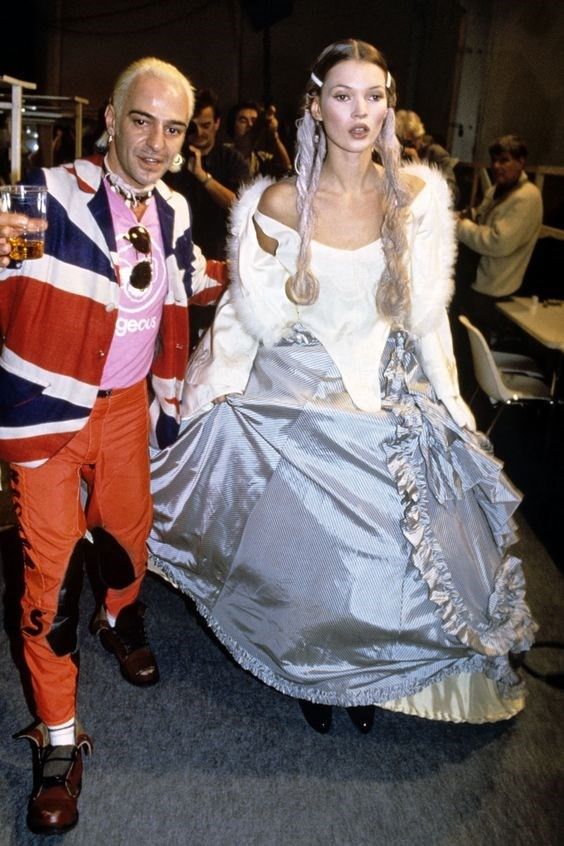

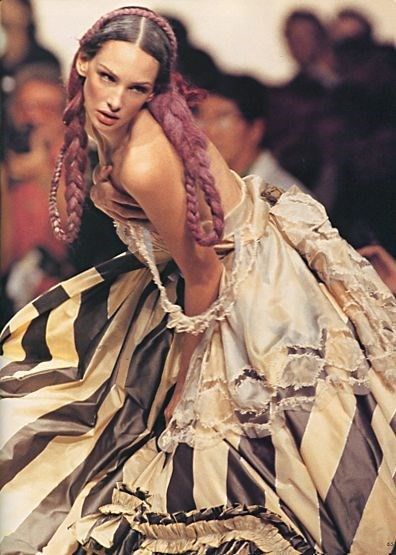

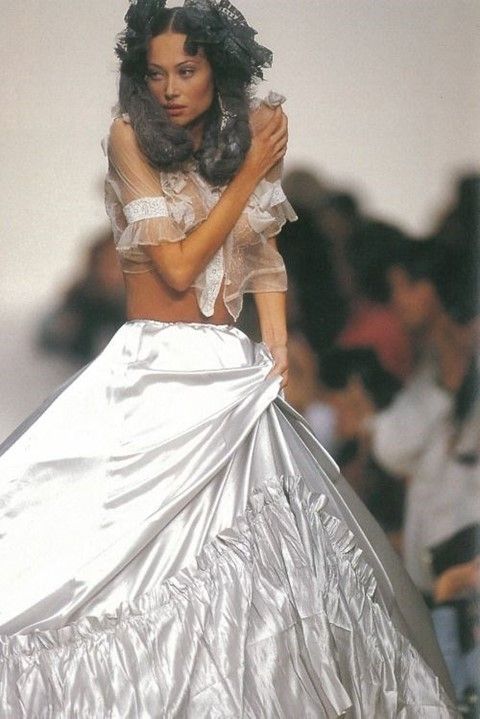

The last topic we address together with Valerie Steele is the value of fashion history in relation to cancel culture, just days after the release of the documentary about John Galliano, High & Low. In this case too, studying the past proves useful. «In a world where things tend to be very polarised, I think it's necessary to understand the kind of pressures people were under. The industry was ferocious; I remember hearing the videotape of Galliano—it was absolutely horrible and despicable, but it was also clear, in many ways, that he was very, very sick,» says Steele. In Steele's completely comprehensive and attentive view, art can be separated from the artist, because just as we still listen to Wagner or appreciate Picasso, we can still recognise the enchantment and richness of the creations Galliano made in those years of terrible downfall. It was indeed a collection by the former creative director of Dior that André Leon Talley referred to in the documentary dedicated to Turlington, the SS94 by Galliano that told Tolstoy's Anna Karenina with extreme poetry and drama. "One word: the master technician of the twenty-first century," then-Vogue artistic director had announced, foretelling the recognition the creative would receive thirty years later. Because fashion is art, especially when it is colored by strong emotions like the need for redemption.