The crisis is in fashion, not luxury When Fashion Week loses its meaning

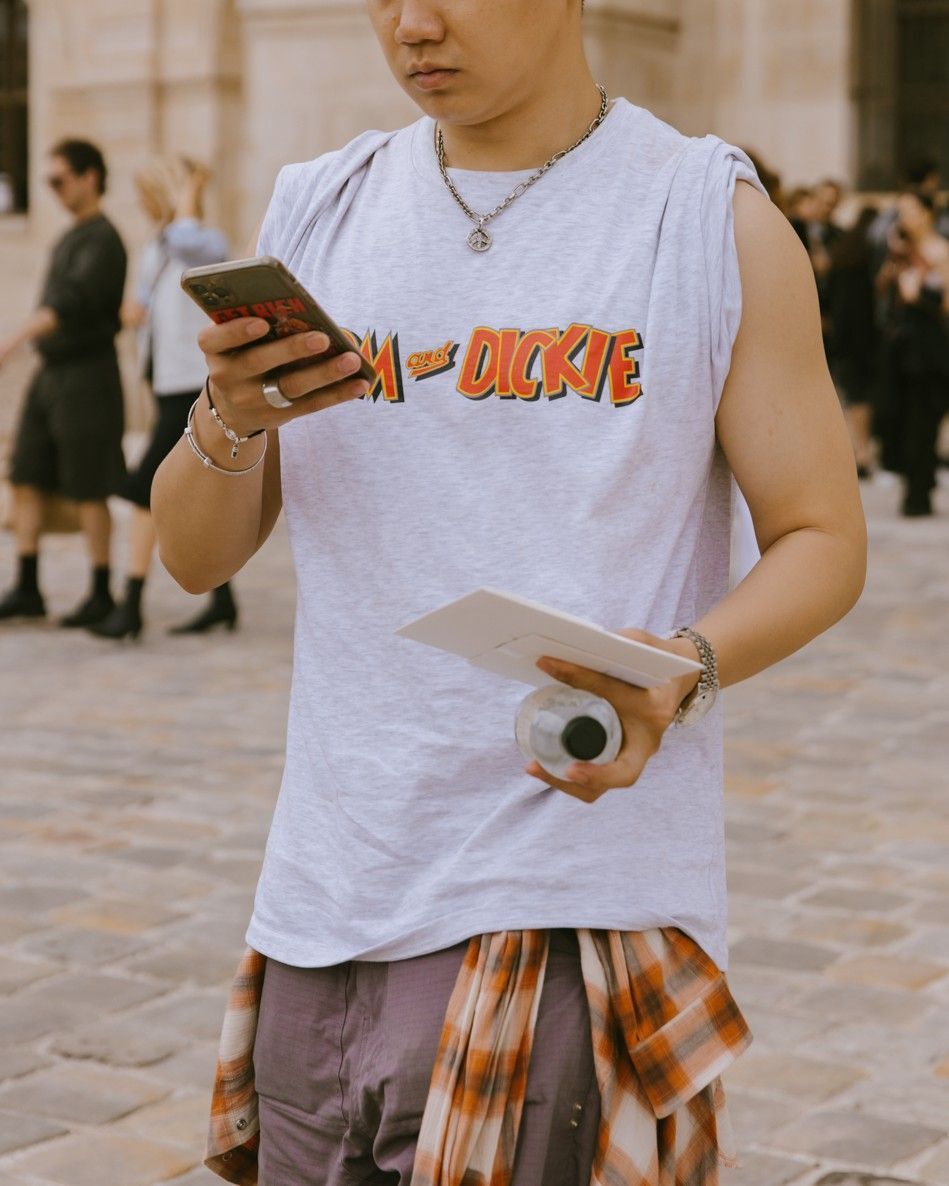

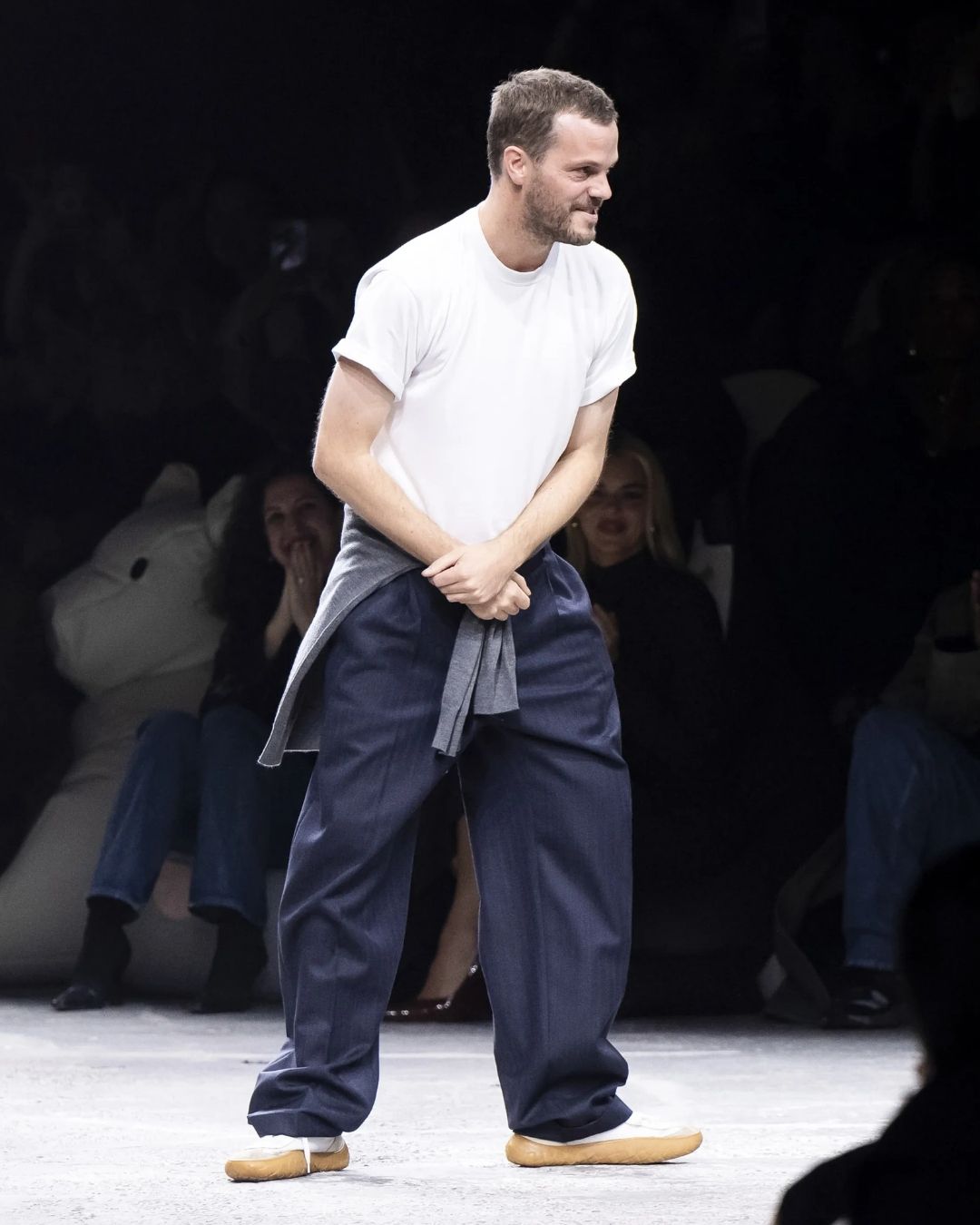

One of the occurrences that has characterized this fashion season has involved two designers most beloved by critics, Peter Do and Glenn Martens, who walked the runway with their respective "corporatized" brands, Helmut Lang and Diesel, but who have chosen not to organize shows for their more independent projects, namely Peter Do's eponymous brand and Y/Project. This happened in a season where even in Milan several independent and highly appreciated brands such as Cormio, Act N.1, or Andreadamo preferred presentations over runway shows - a strategy also followed in Paris by brands like Rochas, Quira, and Paloma Wool. All choices can be interpreted as the desire to invest differently the considerable funds that usually end up being poured into a show of about twenty minutes. This is relatively normal for smaller brands in an absurdly saturated fashion market but becomes something anomalous when a big brand decides to forego such an event: a case that truly occurred this week when Dior canceled the destination show it had planned for Hong Kong for «commercial reasons» not specified, which would have cost a whopping 12 million dollars, involving over a thousand VIP visitors and their entourages.

Oh dear...

— NightMarket (@Night_Market) February 24, 2024

"Source familiar with company says management of French luxury brand decided to postpone event in face of China’s economic uncertainties."

"Culture & tourism chief Kevin Yeung had counted Dior show as one of 80 mega events slated for first half of year."#HongKong pic.twitter.com/0Mn2maV8Mc

If a billion-dollar machine like Dior gives up on a show in the number one luxury market, China, whose economy is starting to stutter, the reason is simple: it's not worth it for them. But speaking about the Chinese economy is complicated: according to LVMH, leather goods sales alone grew by 30% in December just in the region, customers seem to have doubled compared to 2019, and the domestic luxury market, according to CNBC, has a turnover slightly exceeding 56 billion dollars. One might think, perhaps, that just as in Europe, the gap between the very poor and the very rich is deepening (Reuters, for example, wrote last November that 5% of Chinese luxury consumers represent 35% of sales), following the upward trajectory of luxury prices that boosts revenue but reduces the number of actual customers - in short, fashion is becoming even more elitist than in the past. But as designs become more commercial and prices inaccessible, the fashion industry loses artistic depth and approaches a kind of luxury fast fashion: when profit is the only criterion to follow, you play high with markets but low with intellect - minimal spending, maximum return. The elevation of the everyday, which has been one of the main themes of the latest collections, seems increasingly less a search for artistic essentiality and more the glorification of designs easy to produce and sell at unreachable prices.

These clothes are uniformly out of reach for almost everyone, which can make Fashion Week feel exceptionally irrelevant, even "delirious," as one critic described it. The number of designers who spoke of "reality" during interviews backstage this season is an additional irony, albeit a hilarious one». On The Cut, Cathy Horyn spoke of numerous collections that seem «conceived by a sales manager and not by a creative director». Angelo Flaccavento writes, regarding Milan Fashion Week, that «it's as if fashion, understood as a collective system, is attempting an answer, or perhaps better justifying itself, facing the age-old question: in a moment like this, what is all of this for?». The other day Vanessa Friedman instead spoke of «a restless fashion season, in which too many designers have surrendered to the banal (look! a loden coat!)». Even in the pages of the March issue of Vogue, an article expressing perplexity about a luxury whose prices are no longer justified by the classic formula: «You pay for the brand» has appeared. Not to mention how, last November, both the Financial Times and The New York Times dedicated articles to an out-of-control pricing policy that no longer reflects the actual value of the merchandise.

Now, the critical point here is not so much the rise in prices per se, since luxury is by definition inaccessible, and prices vary also based on costs and interest rates, but the fact that, the more luxury sells, the more fashion finds itself in an identity crisis. The industry has become an environment so economically hostile, and the shows such purely performative events, that precisely the brands that do things differently and operate in a well-defined niche prefer not to show at all, carving out their own spaces that can easily do without fashion weeks. Some examples? Our Legacy, Camper, Marsèll, Studio Nicholson - even Tekla has become a modern cult brand by selling sheets and pajamas. Nevertheless, the legitimacy conferred by fashion weeks remains fundamental in terms of cultural recognition - the paradox is that the brands that could choose not to parade, parade; and those that should, prefer to present. Uninterested in social media, and with a very eloquent statement of intent, the Olsen twins had The Row parade behind closed doors this year, with a ban on taking photos: there may be an element of snobbery, but at least the brand does not pretend any democracy by aligning the elitism of prices and that of communication. Conversely, the other day Saint Laurent presented a collection that is entirely transparent and probably, except for coats and shoes, will not even go into production. But if we're not looking at what we'll buy, what are we looking at exactly?

btw no phones at the show is also a gimmick in the times we currently live in.

— LOUIS PISANO (@LouisPisano) February 28, 2024

Between a market oversaturated with brands and a series of products as replaceable and banal as they are expensive, an evident contradiction has emerged: if it is artistic and creative prestige that justifies high prices, how to maintain it by profiting on increasingly "easy" and commercial products? If prestige is instead qualitative, why do many high-quality brands cost less than luxury ones, or that same quality can be found cheaply in a vintage store? Why have quality and price point become so blatantly disconnected? How can one talk about the "real world" and the "everyday" of clothes when one is moving higher and higher in the strata of the mega-rich? But above all, with the emergence of luxury brands everywhere, what is the intrinsic value of a certain brand or product? Does that value explain why a viscose dress costs as much as a car? The questions accumulate, but nobody wants to give us the answers.