In 2013, fashion was a circus. And now? The eternal return of discord

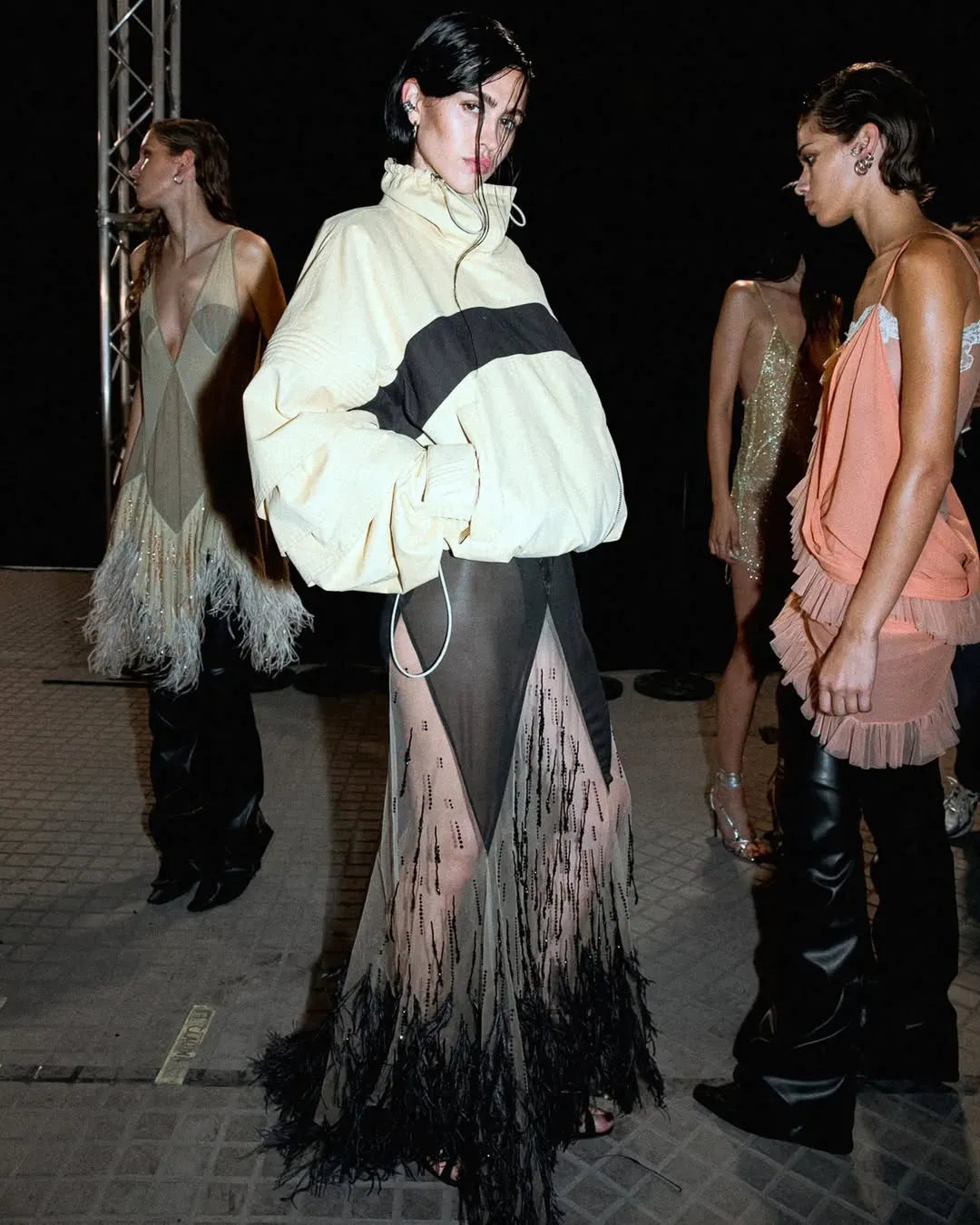

In 2013, fashion journalist Suzy Menkes published an article in the Style section of The New York Times that, even in the title, aimed at the recovery of critical thinking: in The Circus of Fashion, Menkes, contrasting the image of a peacock comfortable in displaying its brightly colored feathers with that of a crow, perpetually frowning in the privacy of its black plumage, spoke out about the media upheaval that saw the opposition between bloggers and journalists. Today, this divide, like an open wound in the collective consciousness of intellectuals, media, and populists, continues to evoke criticism. We are in the years when Anna Piaggi's Doppie Pagine naturally fade away, Chiara Ferragni begins to plan the elements of her media empire from the keyboard of her blog's WordPress, The Blonde Salad, or Bryanboy decides it's right to endorse Marc Jacobs products because they are well-received. Blame it on fame or, as Suzy Menkes puts it, "more accurately on the world of fashion and that circus composed of celebrities famous for being famous. They are known for their Facebook pages, their blogs, and the fact that photographer Scott Schuman has immortalized them on his site The Sartorialist." The publishing industry, despite reserving a dose of life-saving snobbery, had sensed the revolutionary impact of digital, even trying to translate the codes of print into the like-grinding language of the web and social media. Bloggers, however, realize that a carefully crafted image is far more readable and understandable than a word sedimented on the web: some change their skin and become influencers, finding on Instagram the perfect stage to showcase filters, sponsorships, and hidden advertisements.

Influencers vs editors at Fashion Week in the early 2010's https://t.co/3V3OEiiXFr

— EJ Samson (@ejsamson) June 11, 2021

According to Suzy Menkes' analysis, fashion shows have become zoos for two orders of reasons: first, part of the blame is to be attributed to "the crowd of spasmodic exhibitionists eager to be chosen by photographers," while the rest of the responsibility is to be laid on "the way brands, in an attempt to regain control lost due to the evolution of multimedia ecosystems, have entered the game." Ecosystems that, having started with blogs and proto-Instagram, initiated a process of relocating the action from inside to outside the show, now land in complete democratization, involving all social platforms: everyone talks about fashion. From fit checks and get ready with me on TikTok to informative content created by fashion editors and journalists, the weight is almost identical with the aggravating factor that, for those trying to build a career in fashion publishing, there is the risk of encountering long-term classism and precariousness. Given that the balance of power and media influence has shifted from specialized magazines to self-produced content by luxury brands, it is self-evident that the space reserved for fashion criticism has become almost nonexistent: those with the expertise think twice about the possibility of talking about fashion in a certain way because they fear repercussions in terms of image and public relations with fashion houses. After all, doing fashion criticism means entrusting written words with the task of tracing semantic paths that connect the composition label of a garment to its interdisciplinary exegesis - how does it marry with fashion in its purest form of entertainment?

@bellagerard Wait til the end Editors that freelance and influence on the side are industry Hannah Montanas for real @Belle Bakst | NYC Shopping #editor #fashioneditor #nyclife original sound - Bella Gerard

Probably a matter of formats. However, 2023 has taught us that even the work of creative directors, those mythologized and put to the test by the mass consumerism of the fashion industry in the '90s, could be thoroughly questioned by CEOs and managers who are relatively uninterested in fashion. Fashion campaigns, produced indiscriminately by a luxury brand or a fast-fashion one, become problematic when dealing with cognitive biases, conspiracy theories, and functional illiteracy. In summary, we were and still are totally unprepared to face a corporate crisis on the online front. Not to mention the editorial field: in May 2023, the Vice Media Group, valued at $5.7 billion in 2017 with a business model based on the free consumption of digital content and advertising revenue, filed for bankruptcy. Highsnobiety, a German media platform founded in 2005 and acquired by Zalando in June 2022, stated to BoF that it has laid off 10% of its staff "rationalizing our global structure to align with ongoing changes." A realignment that, a few months ago, also hit the Condé Nast editorial group in the form of a 5% layoff of its employees (about 270 people), mainly from the video division. "Although Condé Nast's short-format video channels have helped drive audience growth, the publisher has struggled to monetize engagement. Seeing a decline in advertising revenue in print, over the past ten years, several publications have tried to diversify their revenue streams, with titles like GQ and Vogue investing in video content and launching subscription programs," explains BoF.

Blame it on metrics, once again — it's all a matter of measures and weights. The eternal debate between journalists and influencers found an unusual interpretation when a fashion critic of the caliber of Cathy Horyn, h ired as a model by Balenciaga for the SS24 collection, came under the media spotlight, just like Kim Kardashian in the role of curator for the SS23 collection of Dolce & Gabbana. Although the former uses newspapers, pens, and keyboards, while the latter perfectly embodies the switch from senior influencer to international celebrity, their function has been salvific for different brands and scenarios: shielding them from a crisis. It's strange, or perhaps it should simply be framed in this kind of reconstruction, to hear from two creative directors like Stefano Gabbana and Domenico Dolce that "we were the only ones not to work with influencers, we made them walk but never paid anyone. For a year and a half, we have changed our approach, we have returned to working with masters like Meisel and Klein and some models. We like fashion, and who better than them can express this concept? The photographer, like the journalist, has a profession for which he has studied, has a culture, you can have a dialogue on an equal footing," they added before the debut of their latest fashion show in Milan. But who is really investing today in the quality of information as well as in fashion pieces? Among the brands, so obsessed with grabbing media coverage full of looks and red carpets, who has opened its doors to emerging fashion critics? Which fashion house has chosen to support a fashion academy or a university in structuring an interdisciplinary program focused on fashion studies?

Criticism does not aim at engagement, nor does it aim at profit. It is neither a metric nor a performance; it needs time and, above all, space. Perhaps it is time to give it, without succumbing to the instinct of distancing oneself from an evolutionary process of the media for which everyone has been responsible and actors over these ten long years. It would be enough to start with self-criticism, for example. Weighted, sensible, constructive to the point of realizing that the vocations of influencers and critics are completely different. And that, without winners or losers, they could find themselves in the condition of being front row or cell mates, glued to an Excel file of an editorial plan. To try to build a system once and for all, even among those who want to tell fashion in their own way.