A Bursting Bubble: What is the Parallel Market of Luxury? Investigation into the Secret that Could Lead the Industry to Collapse

A Bursting Bubble:

What is the Parallel

Market of Luxury?

Investigation into the Secret that Could

Lead the Industry to Collapse.

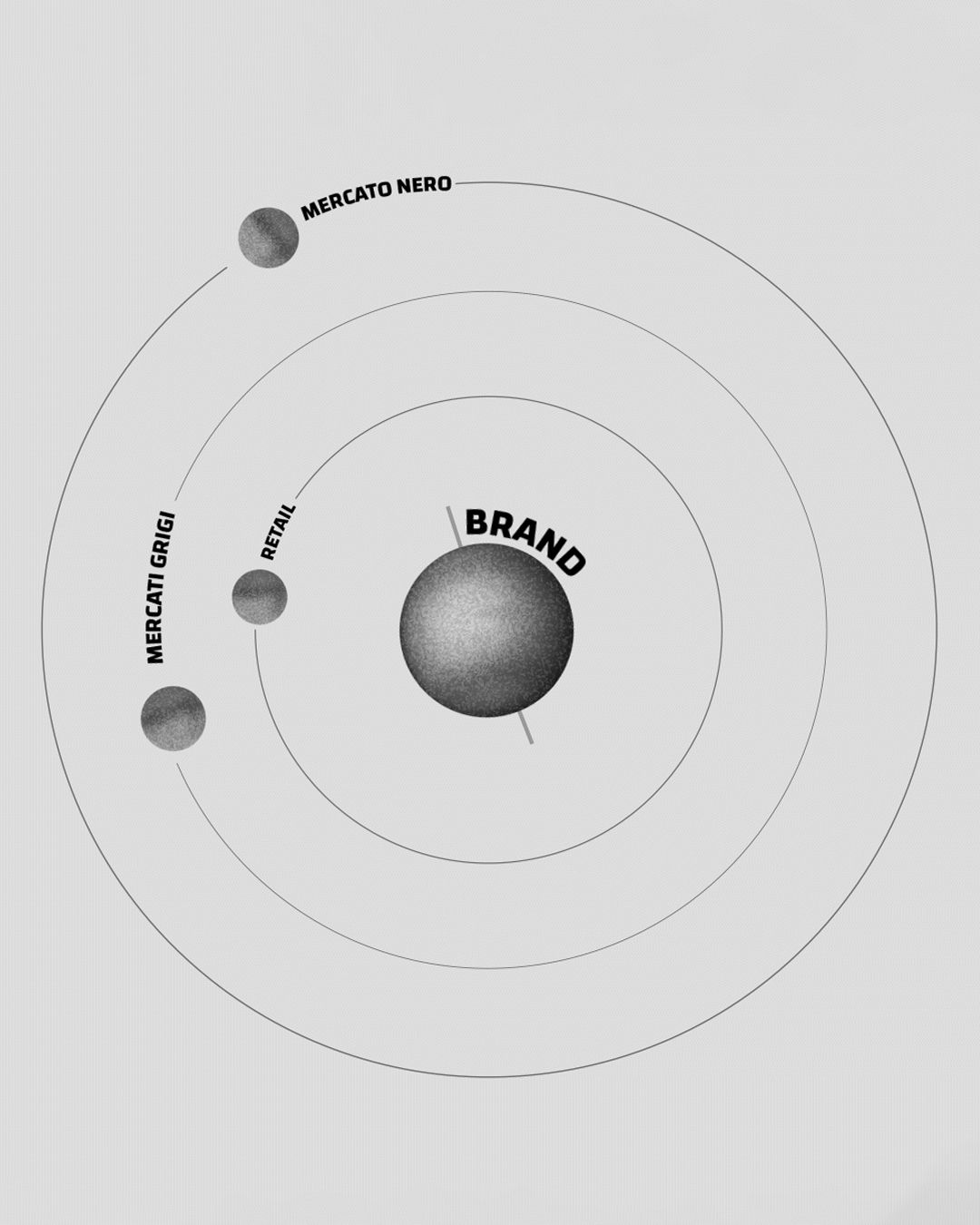

Last April, while presenting its quarterly results during the traditional video conference with analysts, the top executives of LVMH expressed concern about the phenomenon of "daigou", private buyers who import goods purchased more or less indirectly to evade taxes and resell them through unofficial channels, practicing prices contrary to brand listings and fueling the so-called luxury gray market. «For your image, there is nothing worse," commented Bernard Arnault, «it's dreadful». But what is the gray market? If the black market concerns stolen, counterfeit, or untraceable goods, the gray market deals with goods purchased in areas where distribution happens either through direct retail or multi-brand stores. At the same time, the brand is scarce due to its exclusive distribution. It's no coincidence that LVMH, along with Kering, Prada Group and others, «are very, very careful in their contracts with retailers», explained an industry insider who shall remain anonymous. «A thousand clauses specify that the merchandise must be sold only at retail, only in-store, or only through their own website to the end consumer. But they started protecting themselves only because, in the past, the situation had slipped out of their hands». The parallel or gray market (technically called "the parallel”) is a secret that «no one talks about», as other sources have told us, a symptom of «a system that is leaking from all sides» keeping the margins of retailers high despite the retail crisis, and helping brands record healthy sales growth percentages by falsifying the actual performance of all parties involved.

How did the parallel market originate?

«The parallel market originated in the 1990s for the Japanese market,» explained the manager of a retailer who shall remain anonymous. «The Japanese went crazy for Italian brands that were completely closed in those years. So they came to Italy and bought, bought, bought, and then resold them in their country through various channels that could be unofficial physical stores, websites, or even teleshopping in some cases». Over time, the market has evolved from individual buyers to entire companies managing huge cargoes and million-dollar turnovers. Margins for those selling to other sellers are calculated in tens of millions. The channel moves from Italy to Asia: «from here, the goods are shipped to Hong Kong», our source explains, «and from Hong Kong, who knows. Everything goes to China, Korea... who knows where else». Another retailer talks about routes all over the world: «Before China, there was Russia. Probably in the future, there will be India, while now the 'parallelists' are focused on South and Central America and South Africa». But do all orders start from Italy? Oftentimes, yes. «The parallel is a purely Italian phenomenon», explains one of the retailers we interviewed. Others mention Germany and Canada; others still blame the USA, but all of them happen to accuse large multi-brand e-commerce, with Farfetch leading the way, opening an entire new category of issues for them.

Going back to Italian territory, the perhaps shocking fact is that the parallel market sustains the life of stores with a ghost economy without which they could not even exist. «A false economy within Italy», as defined by the creative director of a Milan-based brand. «The reason is, unlike all other countries in the world, the presence of numerous multi-brand stores: in Italy per se, we have three or four hundred. Their totality makes 70% but also 90% of their turnover abroad. There are provincial boutiques that invoice seventy, eighty million in sales – who do you think buys all that merchandise?» says another. Faced with the situation, retailers are half accomplices, half forced: «The budgets and data are given to us by the brands», explains a source, «the company has to meet targets, and so we have to meet them too. The system forces you to double up, even if you don't want to. Many historic Italian stores have to maintain seventy, eighty million in turnover. Keeping those numbers is an Olympic sport».

A Game Where Everyone Wins

According to the professionals we interviewed, all of whom claim to engage in this type of sales for at least 25% of their turnover, the entire ecosystem of the country's multi-brand retail exists only thanks to extremely wealthy foreign companies that indirectly purchase to sell with advantageous mark-ups and without substantial taxes. The merchandise sold is «80% accessories, not clothing. The parallel market goes where there are accessories and where there is a logo on clothing», says one of the retailers. This excludes a whole series of brands that already have more or less widespread distribution or are famous in Europe but remain niche. An emerging designer fairly well-known in Milan, for example, said she had «never really seen a case of parallel on our products. There was a season where some stores surprised us, but I don't think it was really parallel, or it was at very insignificant levels». The brands targeted by the parallel market are always the most famous, often enormous, commercial, immediately recognizable, although another source told us that «even the parallel market has evolved a lot; it's not just fixated on those big brands anymore. Korea, for example, is a more sensitive and attentive market to independent brands, so there is a lot of demand for emerging or more niche brands».

However, the most extreme luxury, that of the world's most coveted brands, is less available for the gray market. Distributed through their own retail networks, through mono-brand stores and therefore not available through both physical and online multi-brand stores, the products of these brands are not purchased wholesale: you have to buy them at full price and then resell them with a margin that is usually thirty percent, making their unauthorized trade less profitable. One of our sources speaks of an «unreachable trinity»: «Chanel, Louis Vuitton, and Hermès. Recently, even Dior has tightened its policy, and then Prada, which has always been the most careful and selective in terms of distribution». The market, however, has a cyclical life: «There are years when brands reduce wholesale distribution, and years when everyone opens it. Clearly, it's something that is convenient for companies, whether they are twenty or a hundred million. They don't do it directly; they use a wholesale channel. And what happens on that channel, officially, they don't know». Another perceived advantage for companies is in sales: «The brand today has an interest in growing, right?» suggests one of our sources. Adding that «the price on the parallel market gives you a measure of how much your brand is desired». One of the most important retailers we interviewed also defined the parallel market as «a healthy activity, if we want to call it that, as long as it is controlled by the brands, that is, when it is a small percentage compared to what is the turnover of a large brand. It can be done differently: some do it directly, some do it through partners, some do it through retailers».

How Does the Parallel Market Work?

There are two ways to engage in the parallel market, and both revolve around the figure of the "parallelist", a wholesaler conducting «regular but unofficial» transactions. The first method is the so-called pre-order, and the second is that of the actual daigou. In the first case, the "parallelist" contacts one of the authorized stores of the brand and participates in its order as a kind of invisible partner, buying several million worth of merchandise that is then purchased at Italian prices and introduced into that vast semi-underground network that takes it to the four corners of the world. In the second case, that of the daigou, a single agent goes to a store «and maybe buys fifty thousand euros worth of merchandise. So the boutique gives him a discount of twenty, thirty, or forty percent, and he takes everything home tax-free. Remember that in all markets outside Europe, brands apply geo-pricing to retail prices, which are on average 20% or 30% higher depending on the country and market: a figure that takes into account the local spending power, the desirability of the brand in that country, but also customs and import duties. Gray market operators buy their merchandise in Europe, reselling it with an average markup of 20%, which keeps their margins similar to those of official retailers». Now, these numbers may sound abstract to those outside the logic of retailer trade (which we will return to shortly), but to give an actual measure of how vast this underground market is, according to a report by Re-Hub, the Chinese daigou market has grown by 40% from 2019 to today, reaching an impressive turnover of 81 billion dollars.

While some of our interviewees consider the parallel market to be something endemic («It will always exist,» pontificates one, «where there is exclusive distribution, there is a parallel market»), one of them blames the brands: «It's the CEO who decides from the beginning. They lower margins for big brands. Everyone wants to get close to Chanel, do direct distribution, control the price from start to finish. They increase their margins at the expense of multi-brands that need to sell with a mark-up of 2.5 or more. But big brands markup at 1.9 or 2 with a constrained product and on which VAT must be paid. Companies raise prices and lower margins, retailers don't profit from it, to do so, they would have to sell at the pace of a baker.» It all takes on grotesque tones when «the CEO or the commercial director makes direct parallel agreements to control prices in both markets».

But if the retailers we interviewed were happy to talk to us, what happens in the brand offices is protected by the most ironclad silence. «Managing the parallel market well from a commercial point of view, holding it tight, keeps the price high and does not affect your official sales», explains one of the interviewees. The situation has reached a point where encrypted sites have even been created where buyers can place online orders, turning the semi-submerged economy of the gray market into a kind of e-commerce. Paradoxically, parallel sellers have also created retail e-commerce sites (appropriately obscured in Italy, France, and Switzerland), whose names have also been published by The New York Times: Cettire, Baltini, Italist. Good luck viewing their homepage; it's impossible if you're Italian. It features everything found in boutiques with a discount of several hundred euros. Specifically, Baltini promises up to a 35% discount on over 70,000 different items, including Bottega Veneta bags, Marni garments, Gucci, and Tom Ford, and all conceivable brands. Observing Cettire's page, you notice a Gucci Jordaan loafer, which costs $920 on the brand's official site, sold for $637. In a stroke of supreme irony, these same sites have a section dedicated to sales.

A Healthy Offspring of Late Capitalism

«There will always be shadows», is the final response from one of the interviewees that could sum up the final responses of all. On this side of the market, retailers' understanding stops at the delivery of goods and the million-dollar profit margin that keeps the lights on in boutiques. And even though the trend towards harmonizing prices, strict contractual clauses, and the overall control that brands demand over their merchandise put the gray market in relative crisis, whose margins have decreased significantly compared to ten years ago, eradicating it seems fundamentally impossible. Each interviewee has a different answer. One of them, as mentioned above, attributes the cause to the flattening of corporate goals on mere profit: «Finance is everything. CEOs only want to bring the numbers home; they don't care about the outcomes of the strategy. They will leave anyway after two or three years», adding that the long processes and commercial rigidity of «a Jurassic reality» like fashion encourage new emerging markets to turn to the parallel to speed up operations and get their hands on the merchandise.

Another indicates a similar cause but a different symptom: «At the moment, there is too much product around», meaning brands expect to sell a lot, but this unrealistic criteria lead to the formaton of large deposits of unsold merchandise needing to be disposed of through unofficial but profitable channels that no one wants to talk about. «At the moment, brands need to produce less. We have a problem of excess product and excess sales and business policy. To avoid it, you have to remove the stock, so today, if they don't reduce parallel and wholesale, they won't go anywhere. This bubble will remain and burst – it already has. There are global retailers who currently have tens of millions of unsold stock; they are crying, they have to sell». Would this be the time to invoke, along with Serge Latouche, a happy degrowth? Certainly, a first step would be to talk about it, address the issue, and avoid continuing with maneuvers that only serve «to continue to get off about stock prices, to compete to have the biggest finance, for sheer ego». It's all air, cotton candy, a number written on a screen. A suspicion, however, emerges: if someone doesn't stop the gear, it will break by itself. And at that point, there will be no cotton candy left.

-

Daigou

A Chinese term referring to a personal shopping service where an intermediary or private buyer purchases products abroad on behalf of a client, often to obtain better prices or products not locally available.

-

Direct distribution

A distribution model in which a manufacturer sells directly to end consumers without involving intermediaries such as wholesalers or retailers.

-

Wholesale distribution

The process of selling products in large quantities to retailers, stores, or other intermediaries, rather than to end consumers.

-

Geopricing

A pricing strategy that takes into account geographical, economic, and cultural differences to determine product prices in different regions.

-

VAT credit/refund

A situation where a company is entitled to tax refunds as the amount of VAT paid on purchases and expenses exceeds the VAT due on sales.

-

VAT debit

A situation where a company has to pay an amount of VAT that exceeds the VAT collected on sales, resulting in a tax debt.

-

Mark-Up

The percentage of profit added to the cost of a product to determine the selling price. A mark-up of 2.5 means that the selling price of a product is 250% of its cost.

-

Parallel market

A phenomenon where products are sold outside of official or manufacturer-authorized distribution channels, such as through unauthorized retailers or online channels not directly affiliated with the brand.

-

Monobrand store

A retail store that exclusively offers products from a single brand or designer.

-

Multibrand store

A retail store that offers a variety of brands and designers within its assortment.

-

Retail budget

The planned financial allocation for retail activities, including inventory expenses, marketing, personnel, and other operational costs.

-

Sale target

The set sales goal that a company aims to achieve within a specific period.