Nessun dorma: exploring Pavarotti's style How the Internet turned the tenor into an unexpected style icon

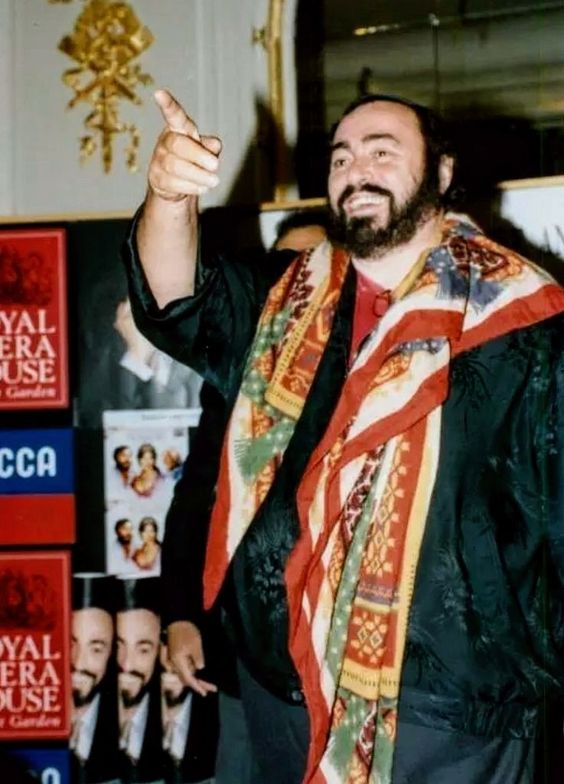

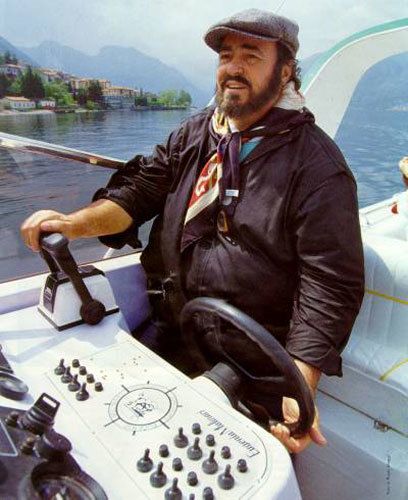

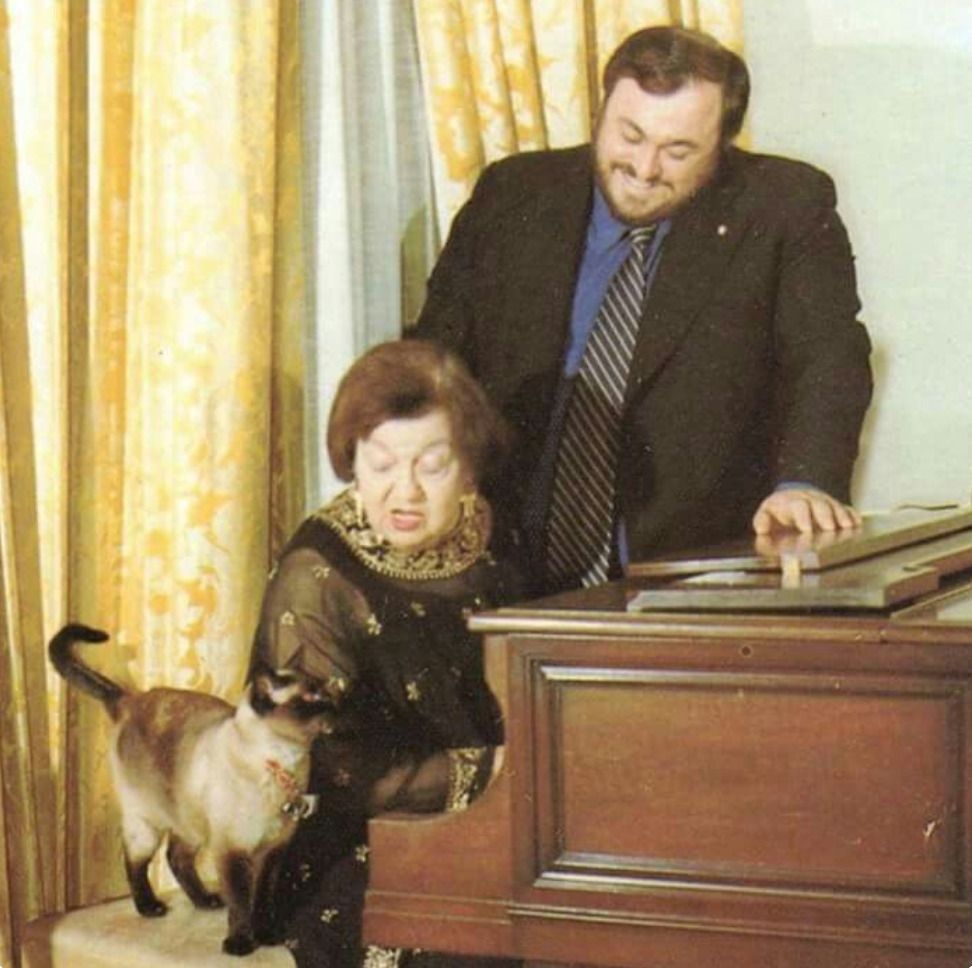

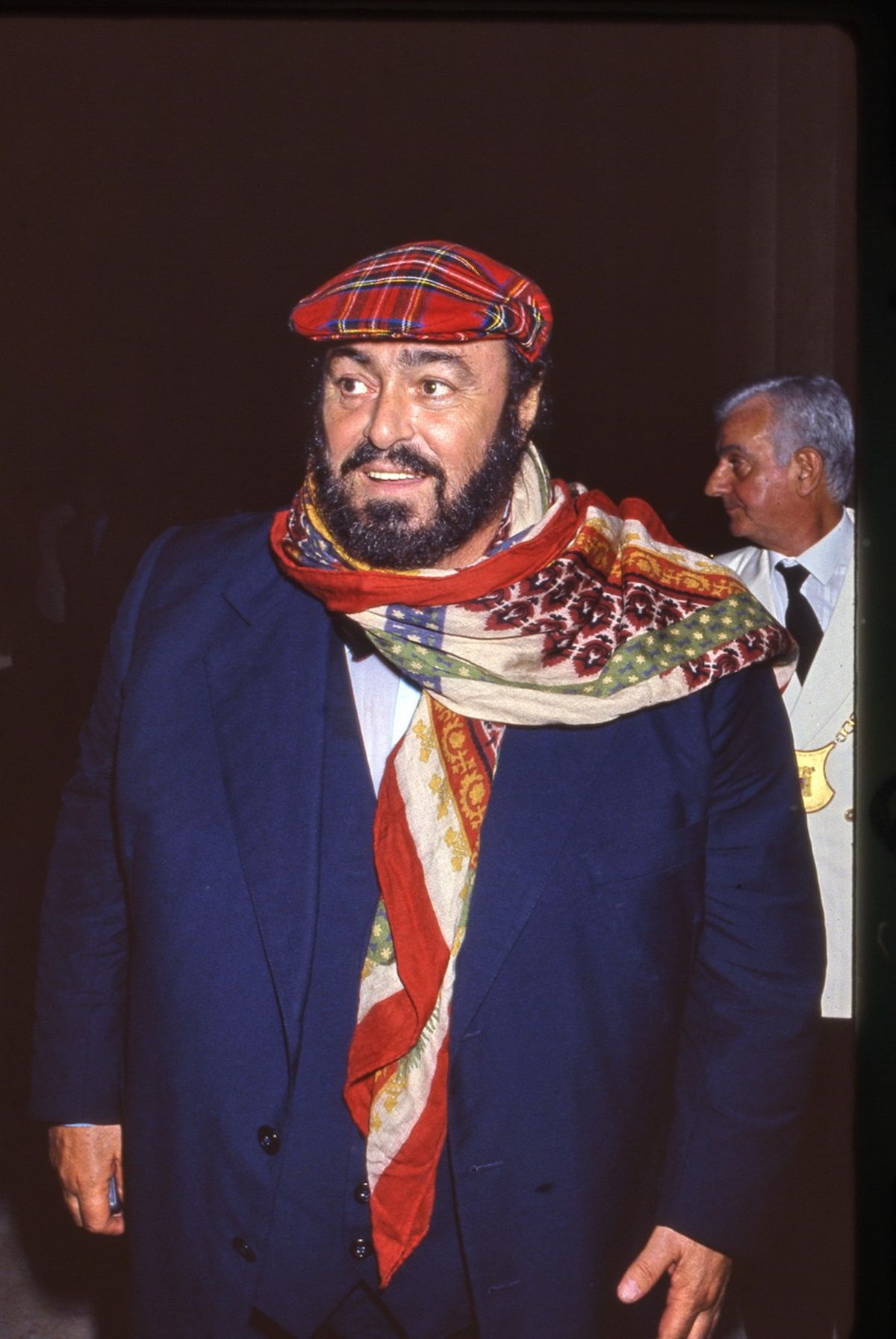

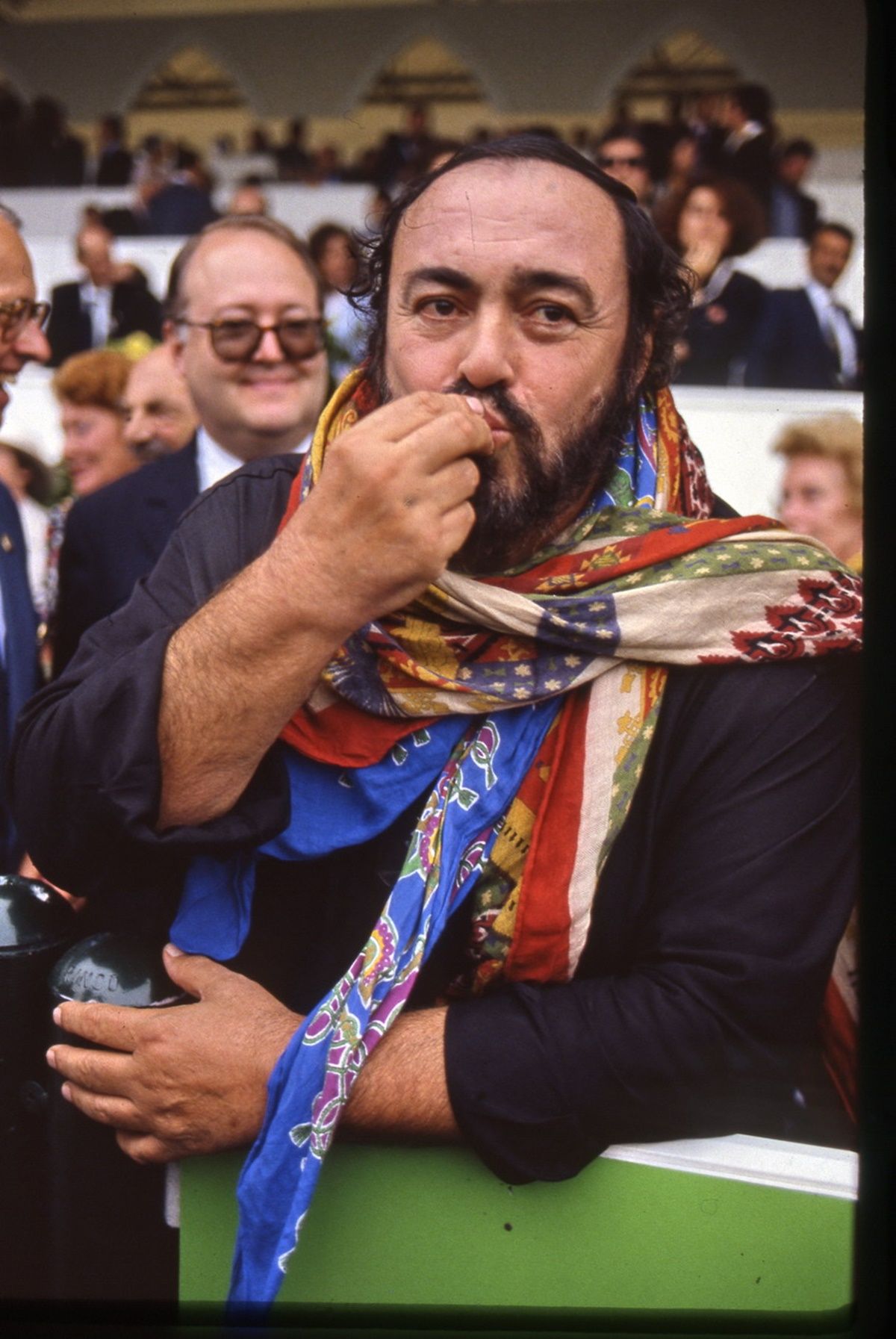

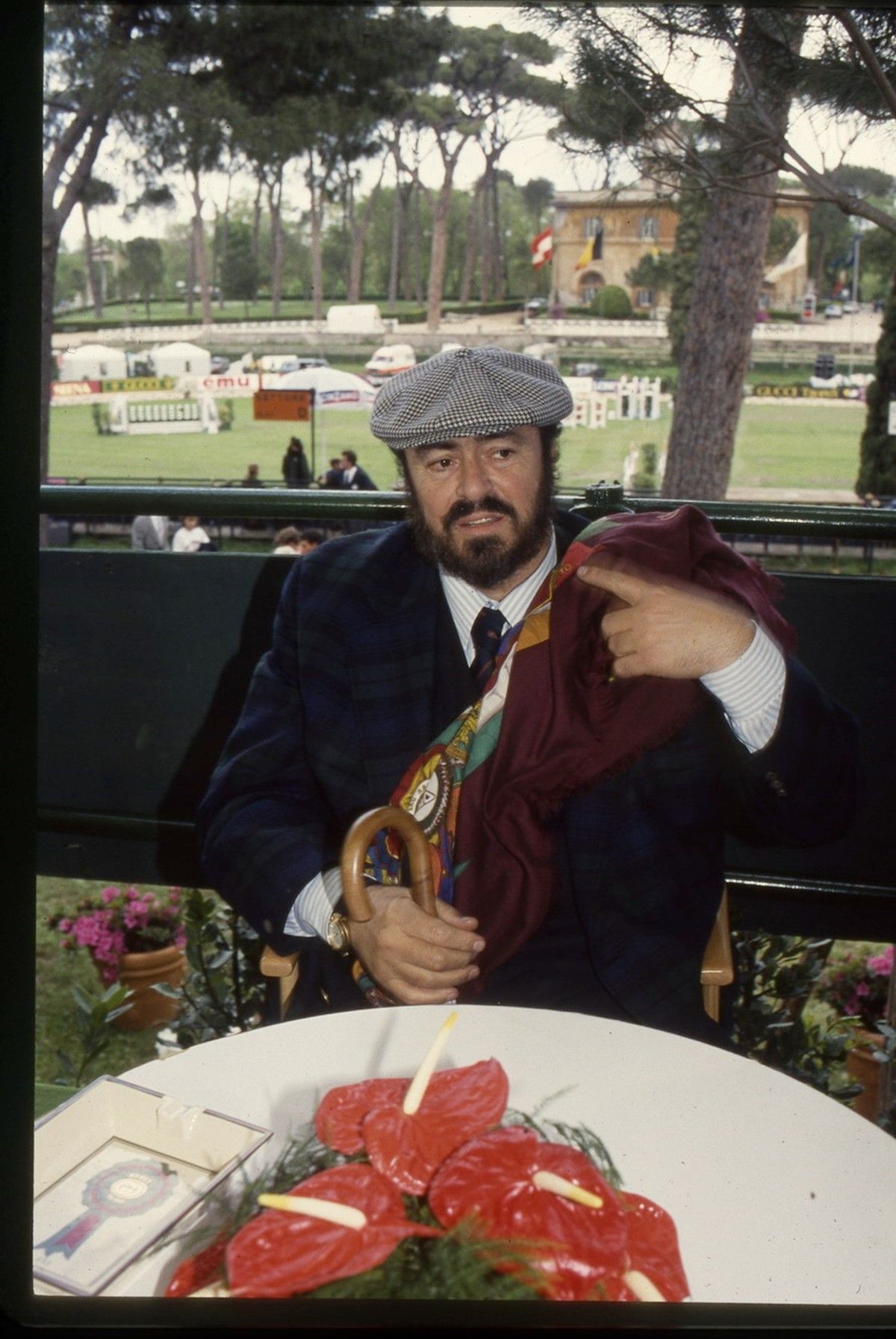

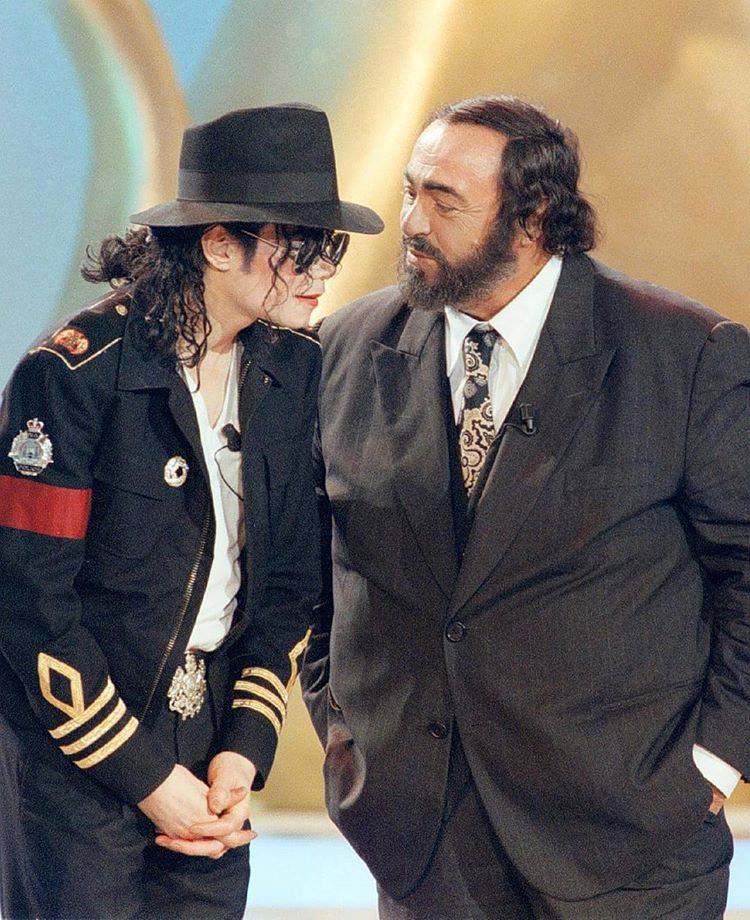

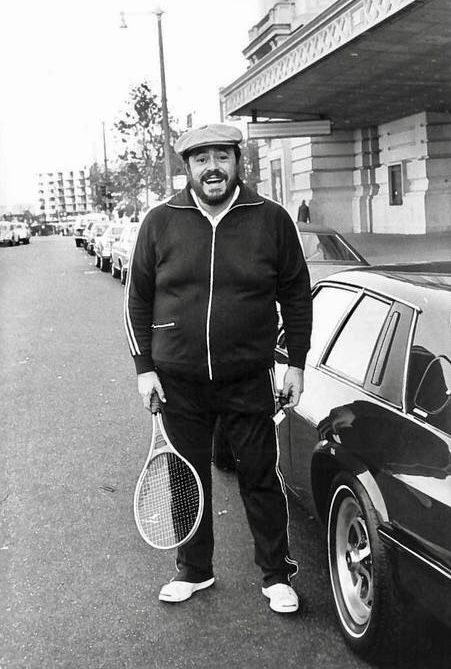

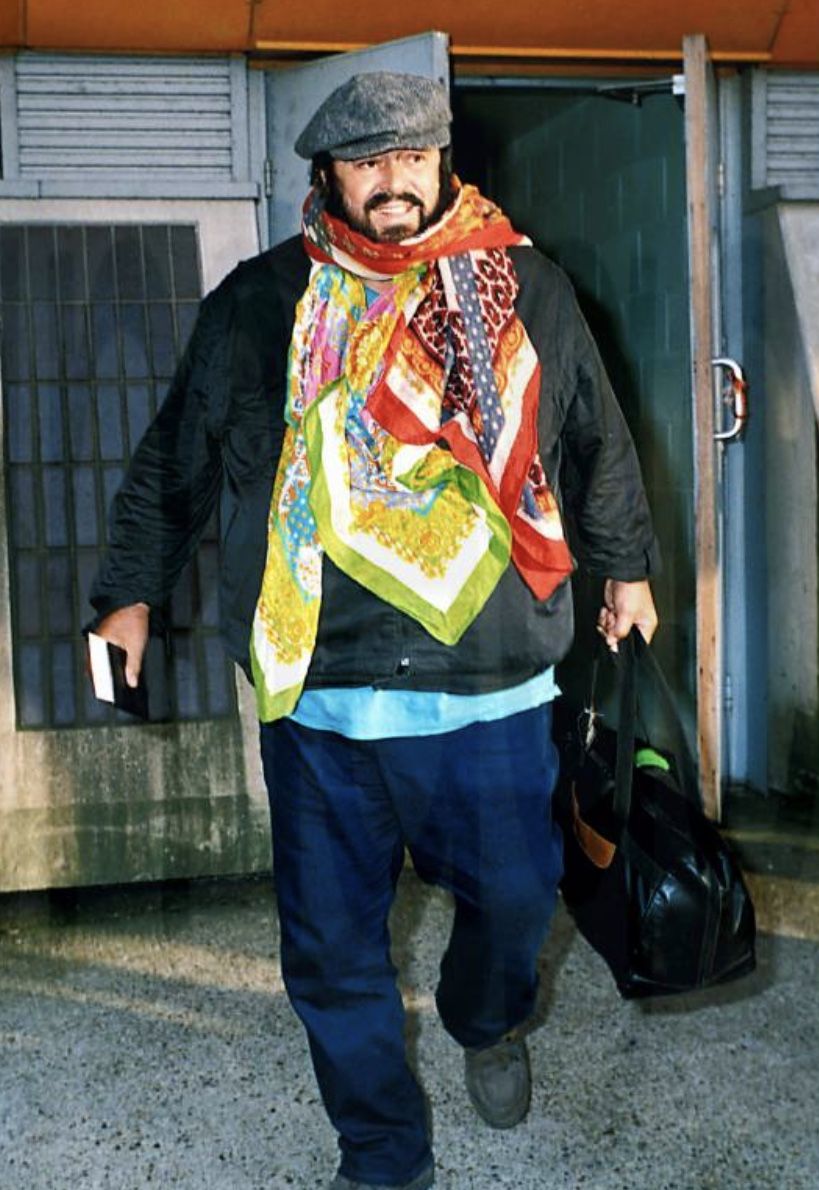

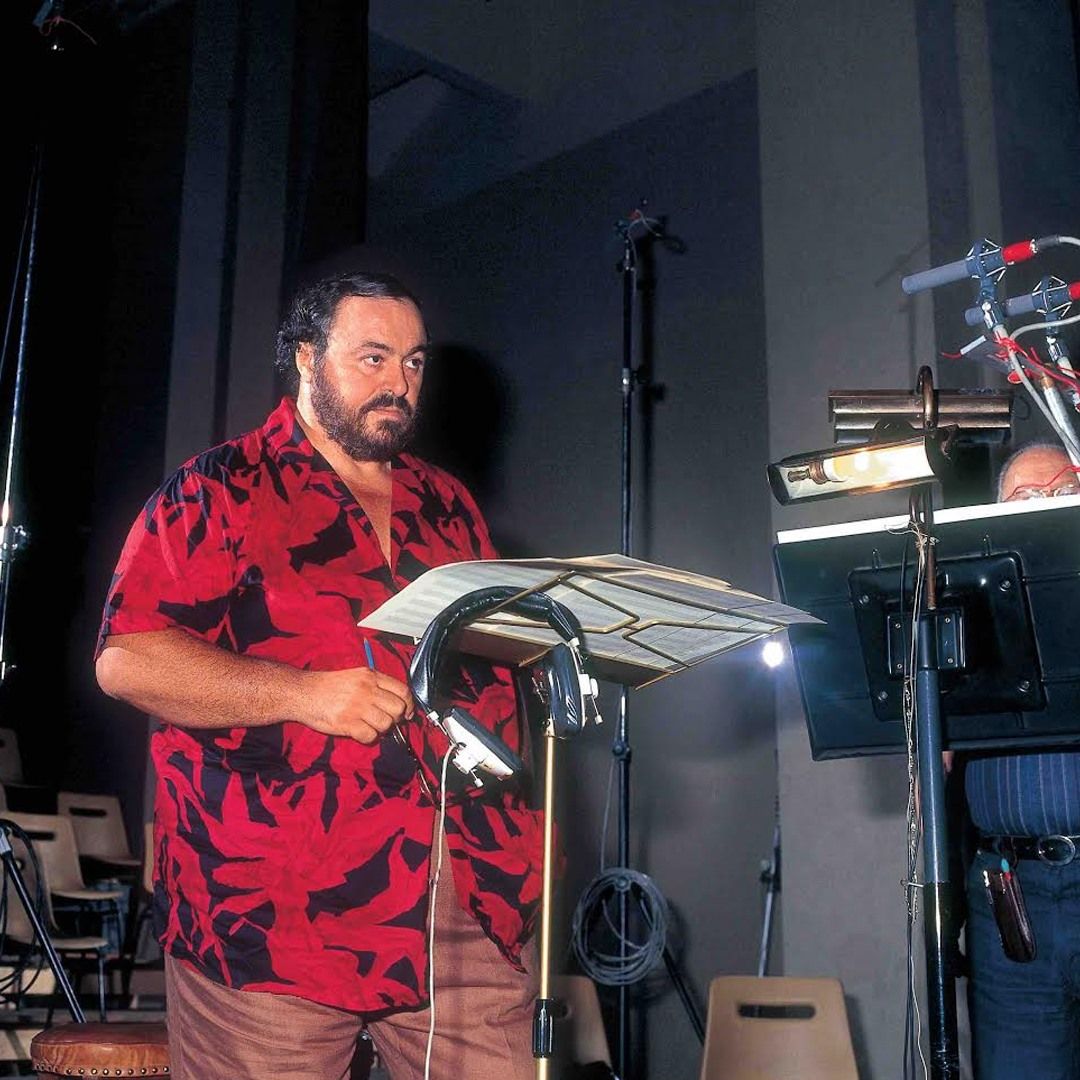

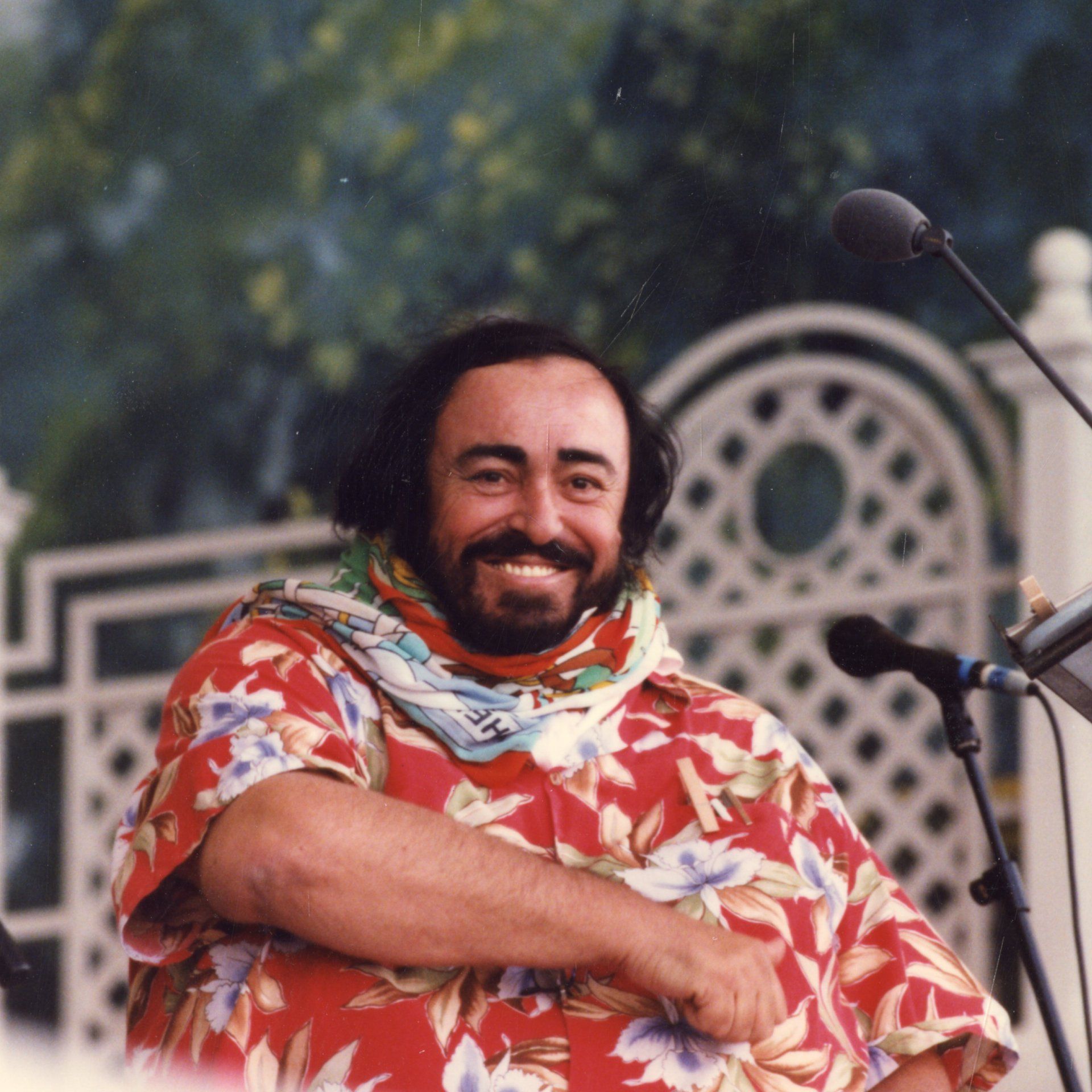

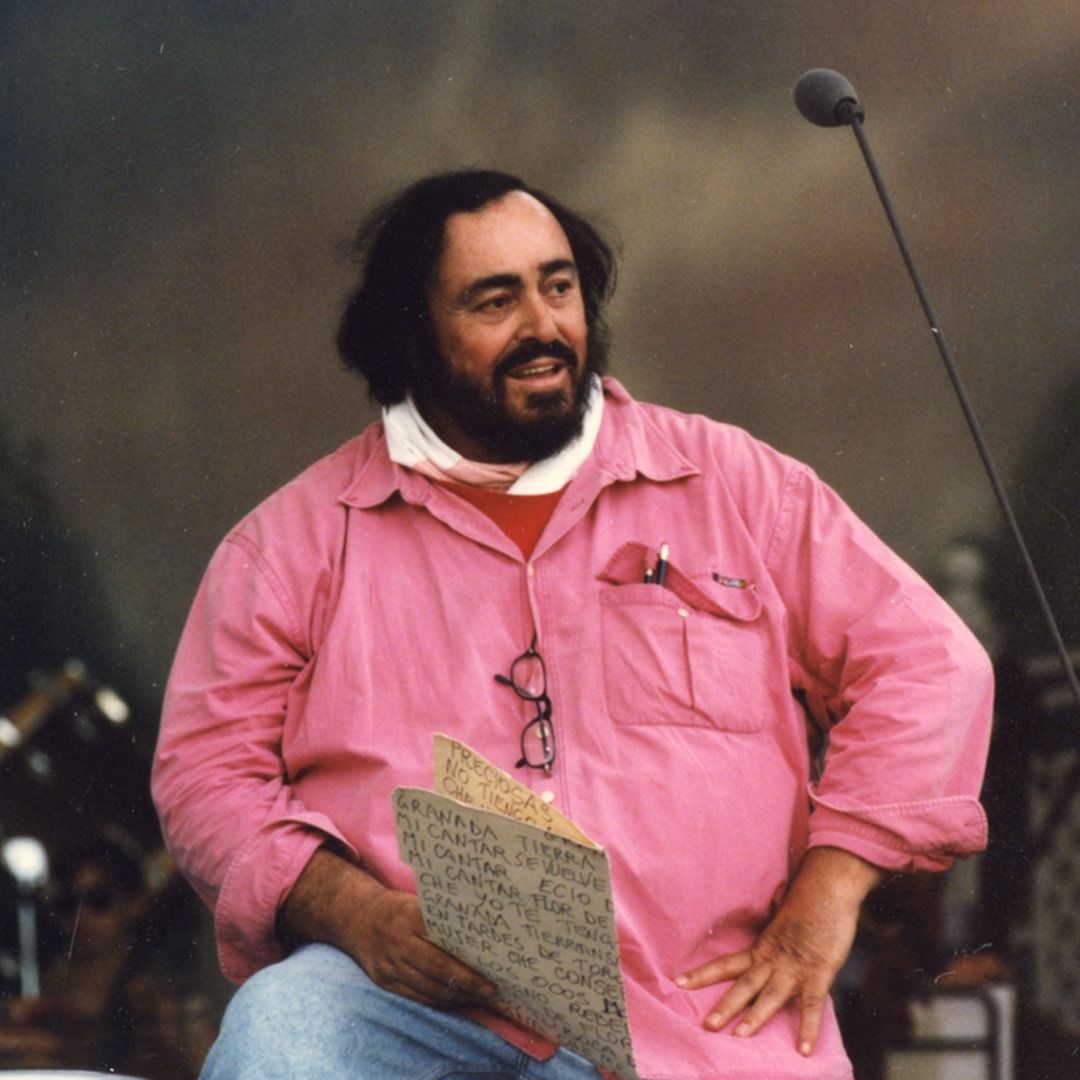

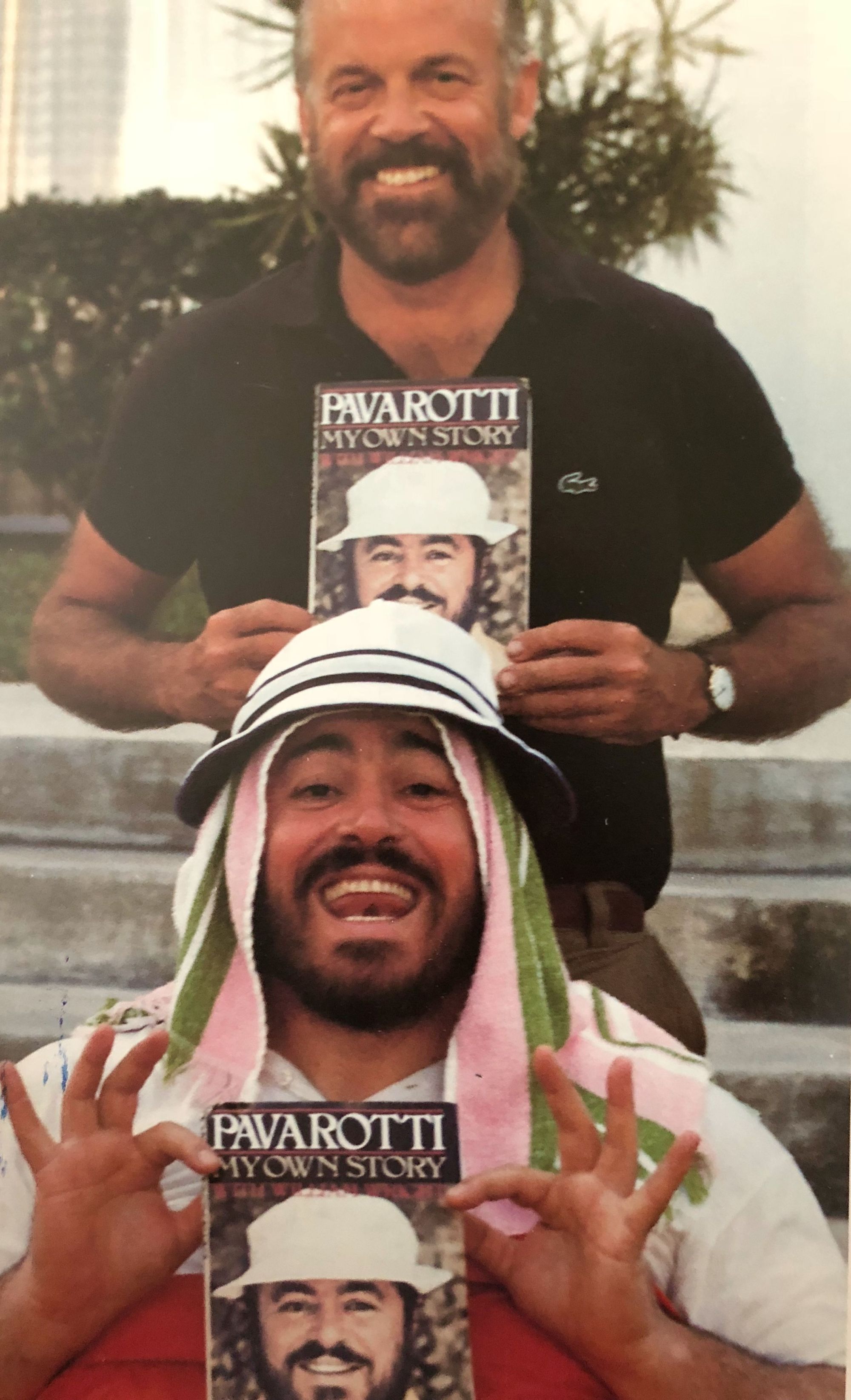

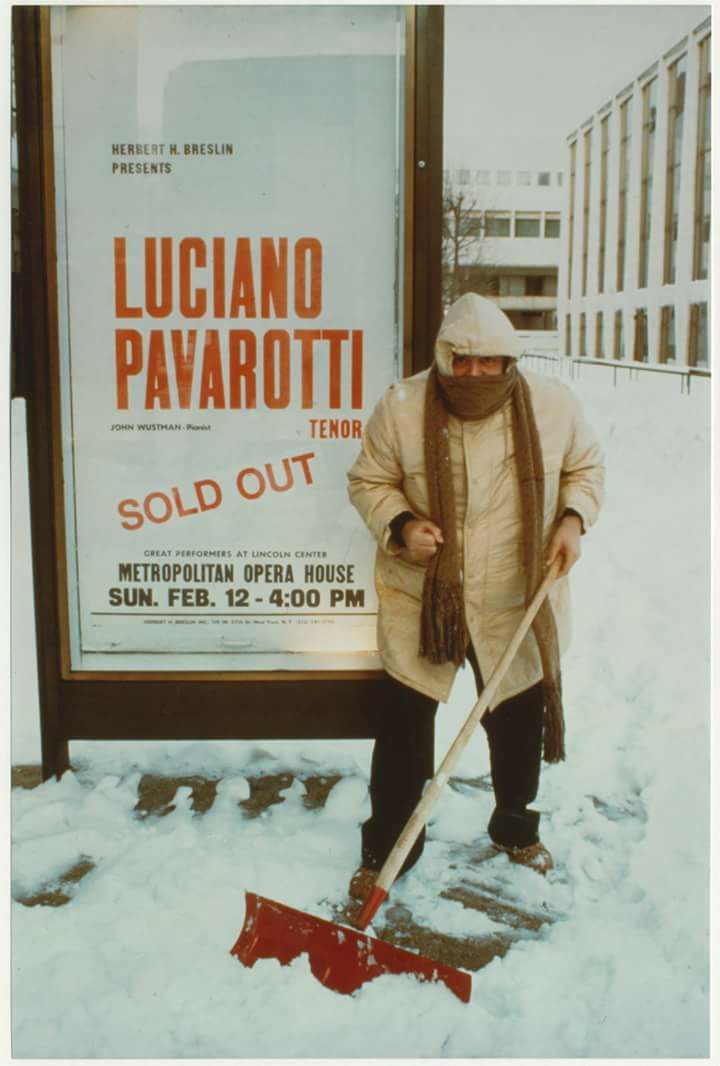

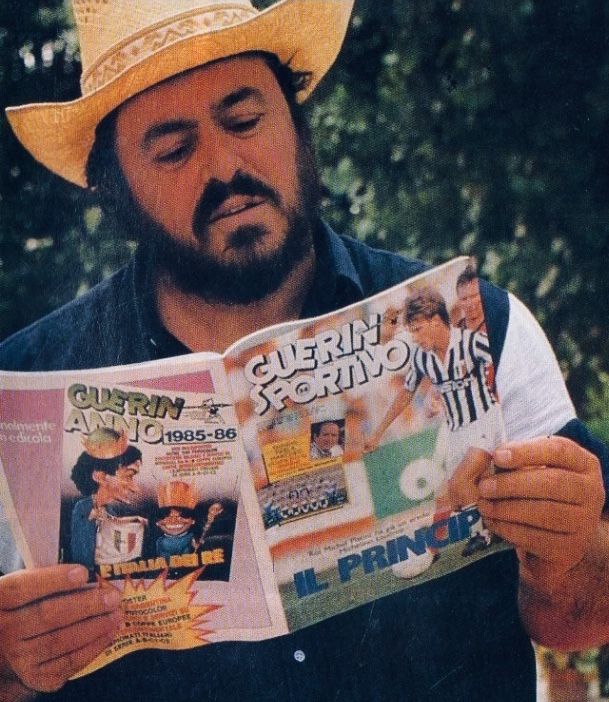

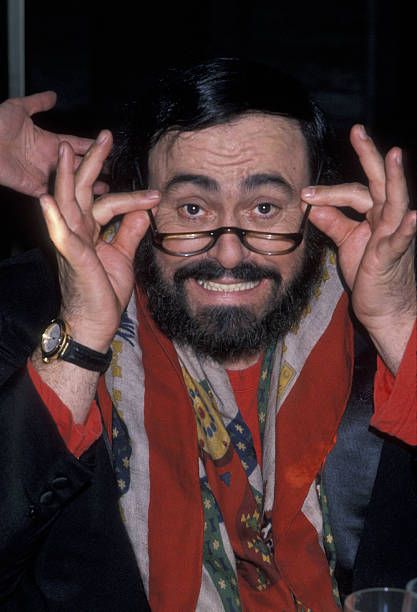

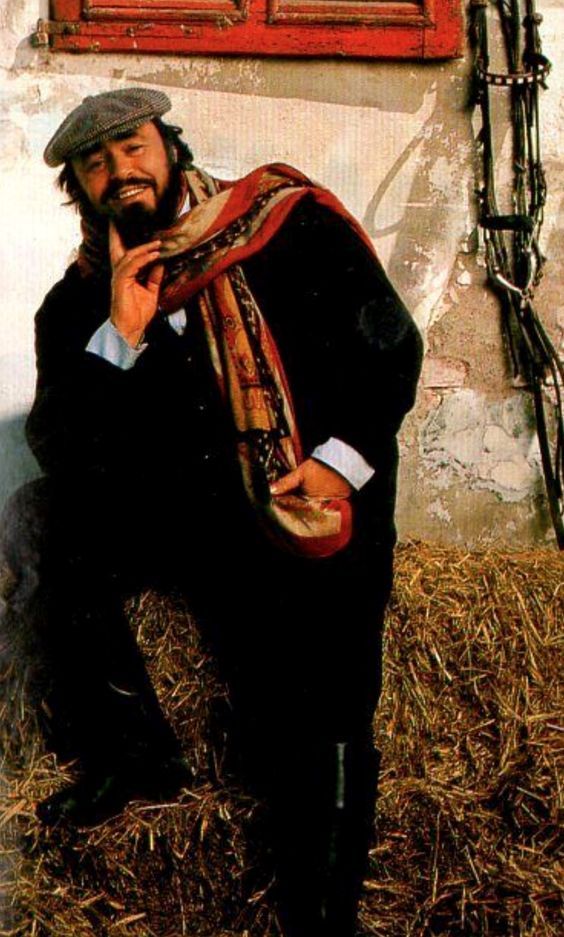

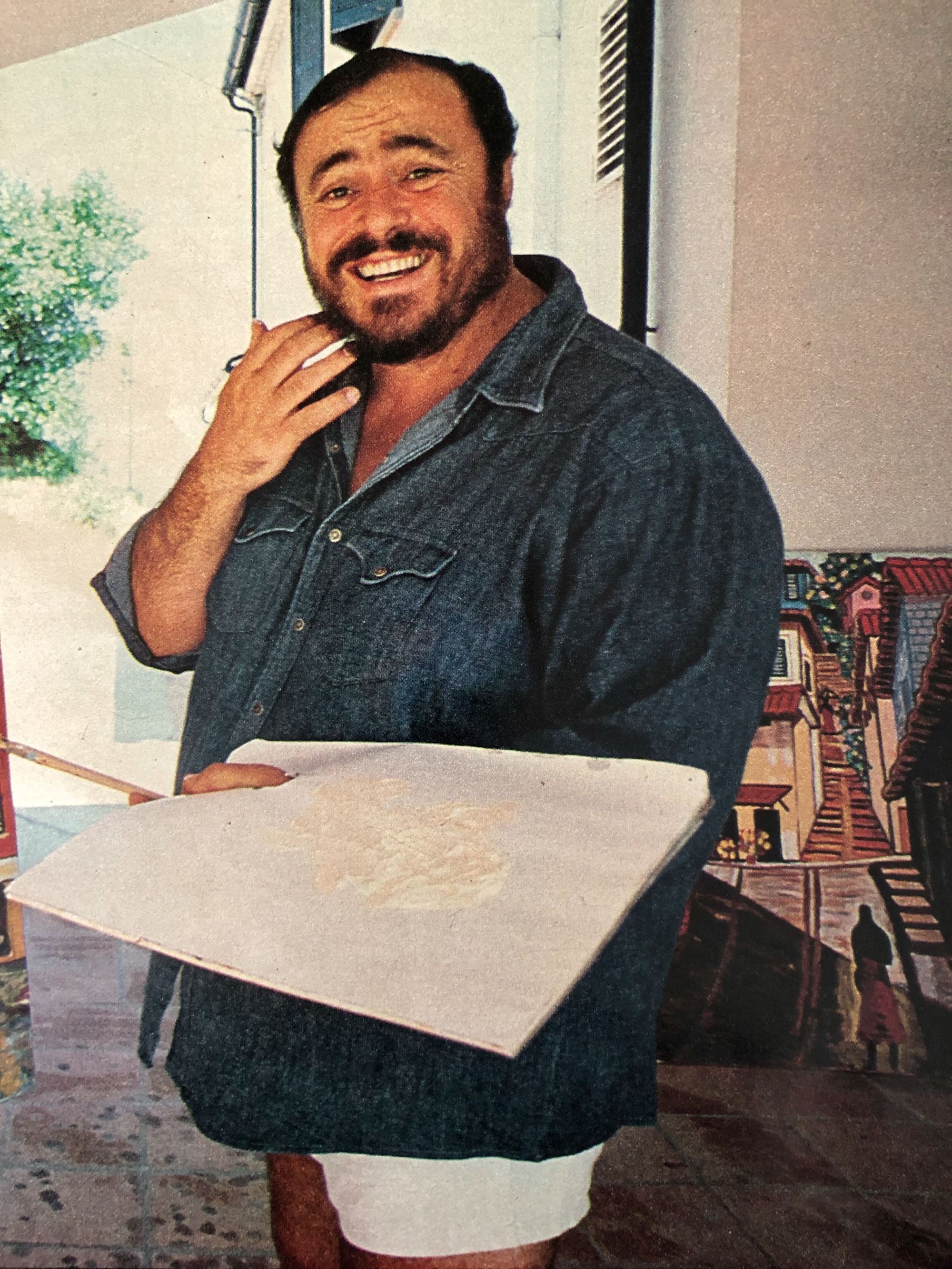

In the history of music, as well as in that of pop culture and real life, Luciano Pavarotti was a larger-than-life figure. Perhaps the primary one, along with Maria Callas, responsible for re-establishing the connection between the aristocratic world of bel canto and popular culture. In 1982, Time described him as «the first tenor of modern times who not only pleases the devotee but also wows the masses». The polarity between the theater and the stadium, so to speak, between operatic and popular music («there is a meeting point between the two», he said in 2000 at the Sanremo Festival, «when the music is beautiful, it's beautiful»), between the elevated and the pop, somewhat defined his very long career, along with his commitment to social causes. But this is hagiography, not pop history. For those born and raised in Italy in the '90s, for Millennials in general, Pavarotti is one of those figures populating the collective imagination without a specific role: young Millennials, not particularly aficionados of classical music, knew he was a tenor but did not fully grasp the world of opera. They remembered his unmistakable appearance with a beard, large black eyebrows, and eyes accentuated with eye-pencil, along with the ever-present smile. He was a paternal figure in his own way. The creation of his persona was also heavily based on his style, which, more than personal, was unmistakable: the classic white scarf, a symbol of all opera singers who take care of their voice; the bottomless collection of Hermès scarves, large as nautical sails, that accompanied him constantly; the Panama hat alternated with the newsboy hat; the vivid opulence of the 1980s colors he wore. Sixteen years after his passing, Pavarotti is an icon, not only of bel canto but of the good life: everything about him, from the unforgettable performance of "Nessun Dorma" to the photos of him riding a scooter on his estate, speaks of a sincere and very Italian vitality.

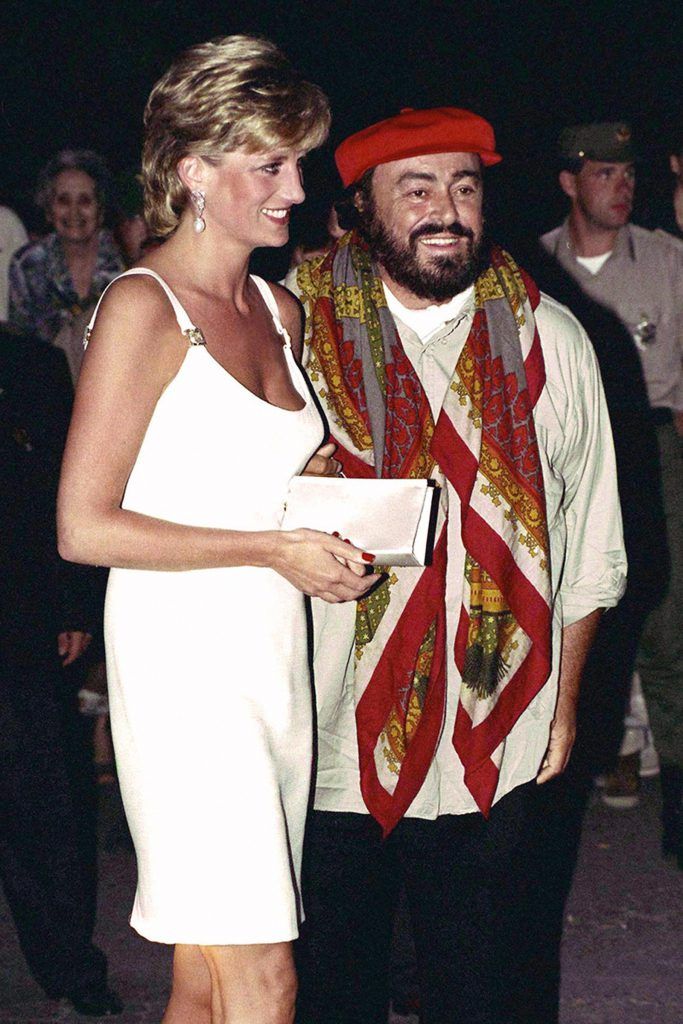

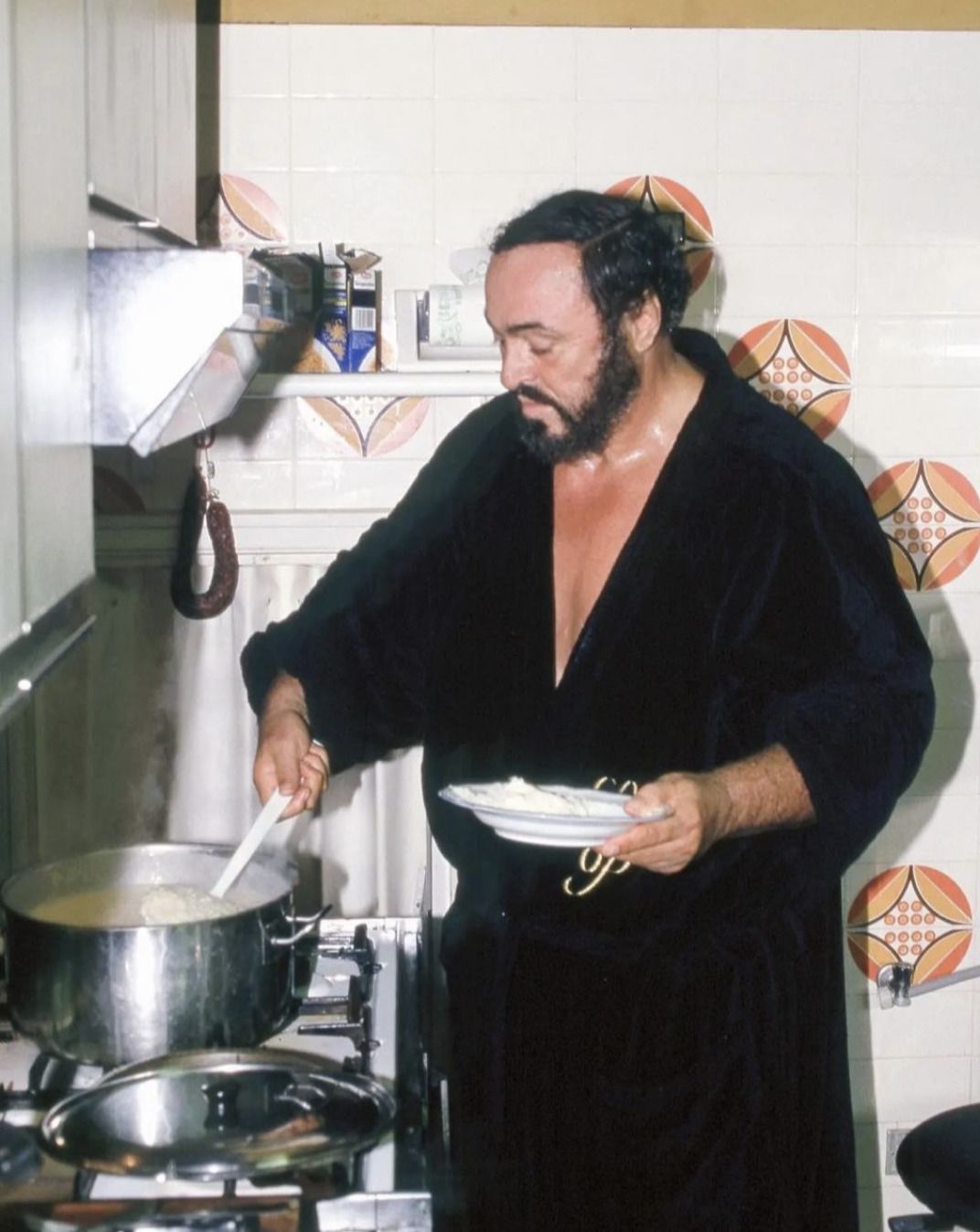

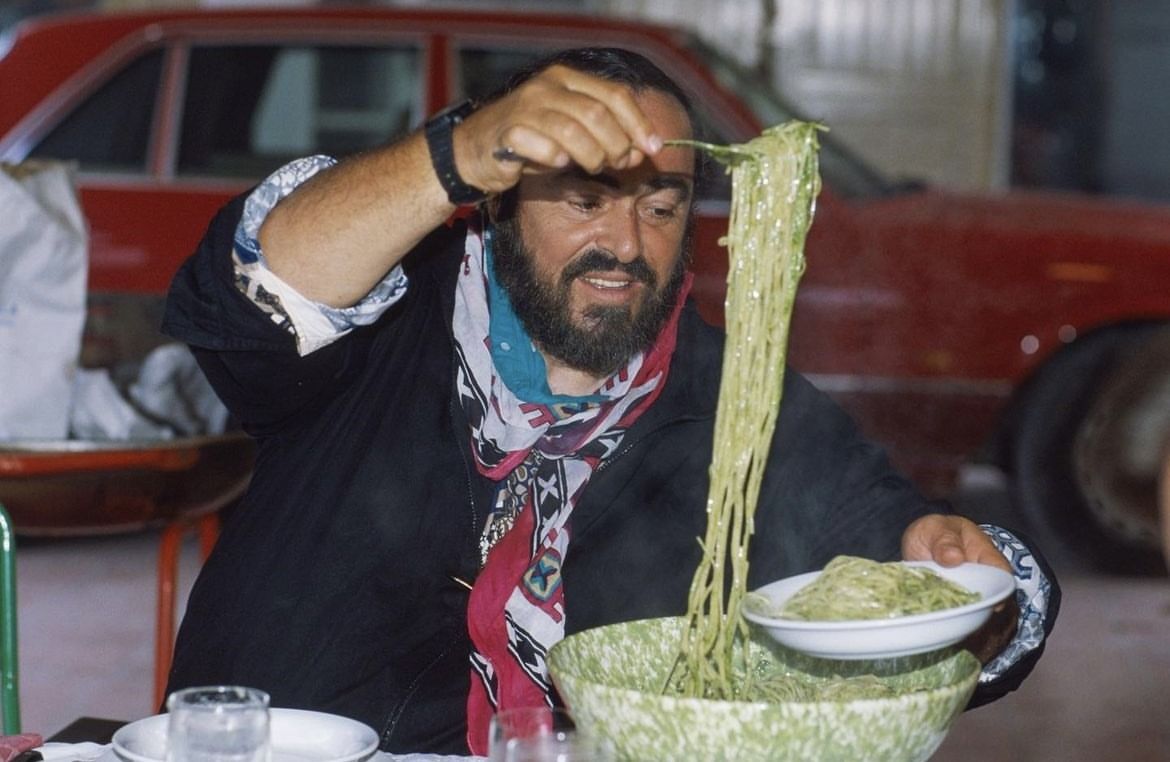

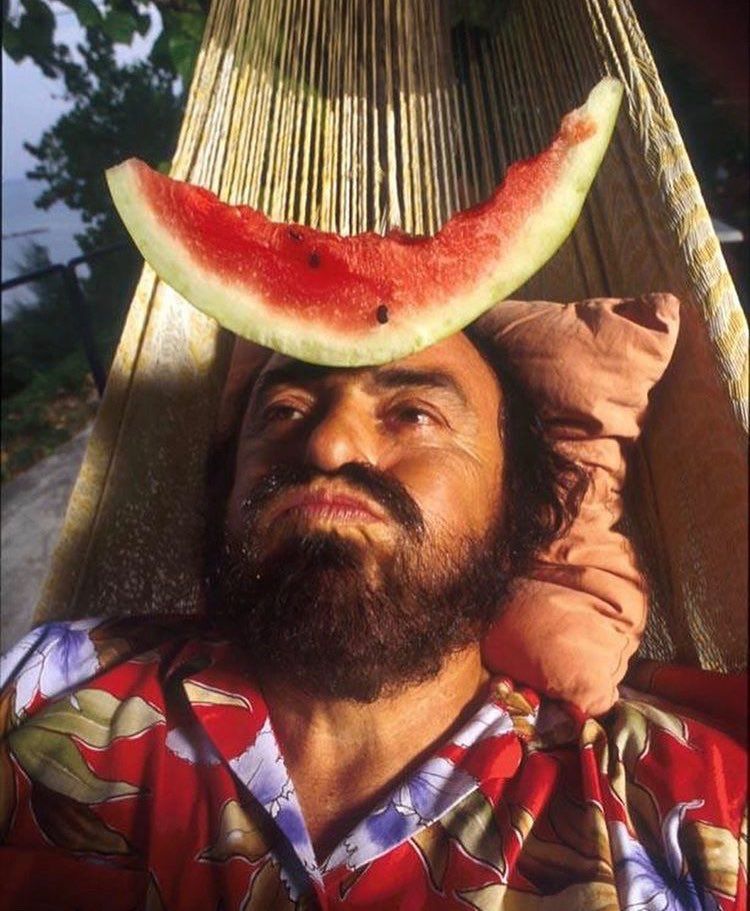

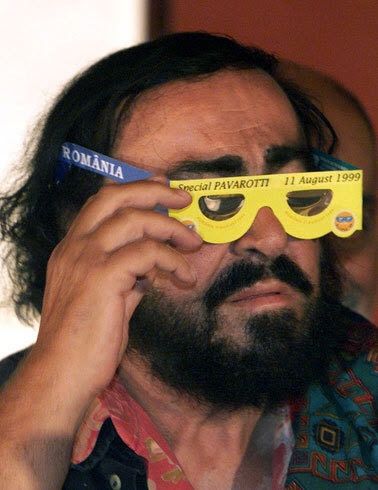

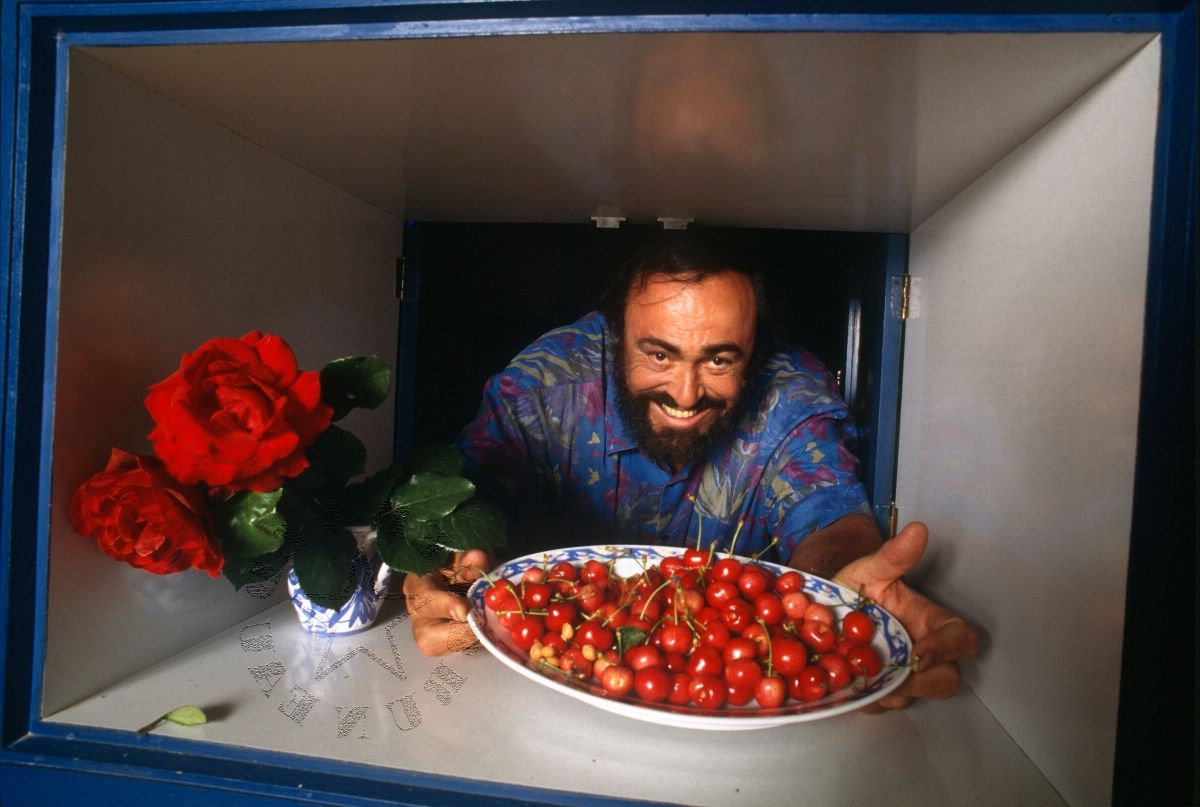

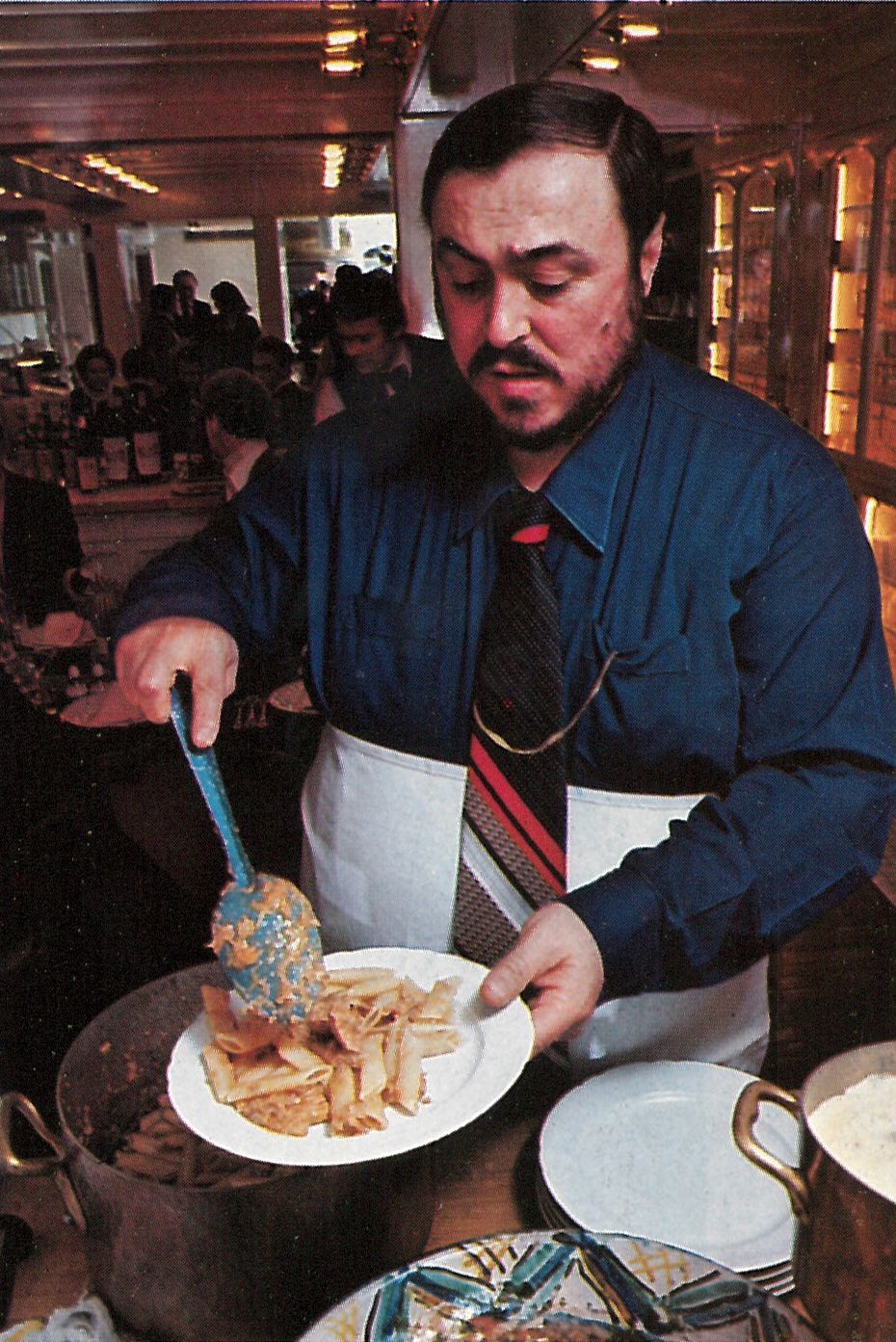

His connection to the collective Italian pop imagery was fueled, outside of his art, by his love for cuisine, of which there are countless anecdotes: the time his robe caught fire while preparing breakfast; the field kitchens set up in the suites of his hotels, with mini-fridges stocked with Parmesan, cured meats, and pasta; the hot chicken consommé waiting for him in the dressing room; the time he forced a crew to "deviate" from Los Angeles to Italy after a concert because in the next destination, Tokyo, they wouldn't have the ingredients for penne all'arrabbiata; or the episode where he tasted Lady Diana's shrimp pasta with his fork, she sitting next to him. One detail from these many anecdotes connects the taste for cuisine, Pavarotti's art, and his personal wardrobe: the large Hermès scarves draped around his neck were meant to hide slices of apple, a fruit that stimulates salivation and has astringent properties that aid singing.

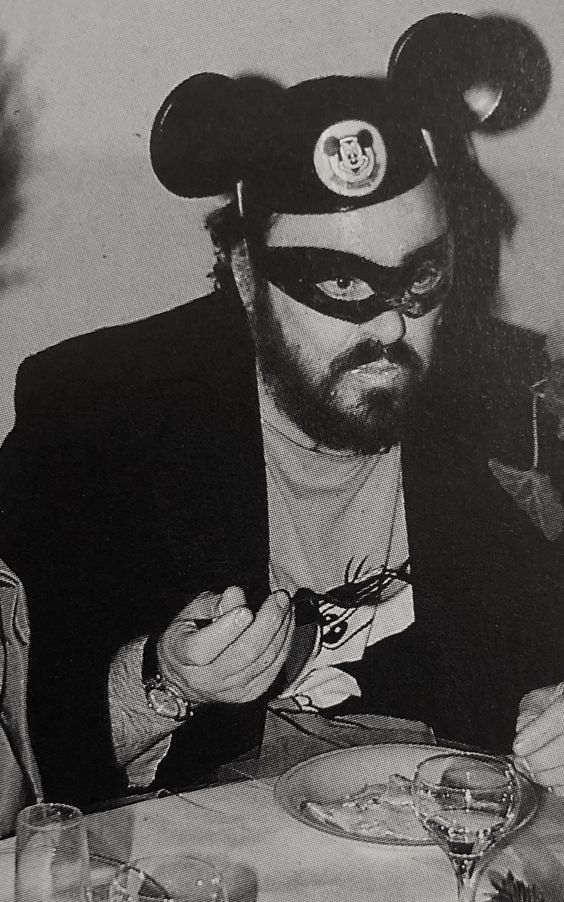

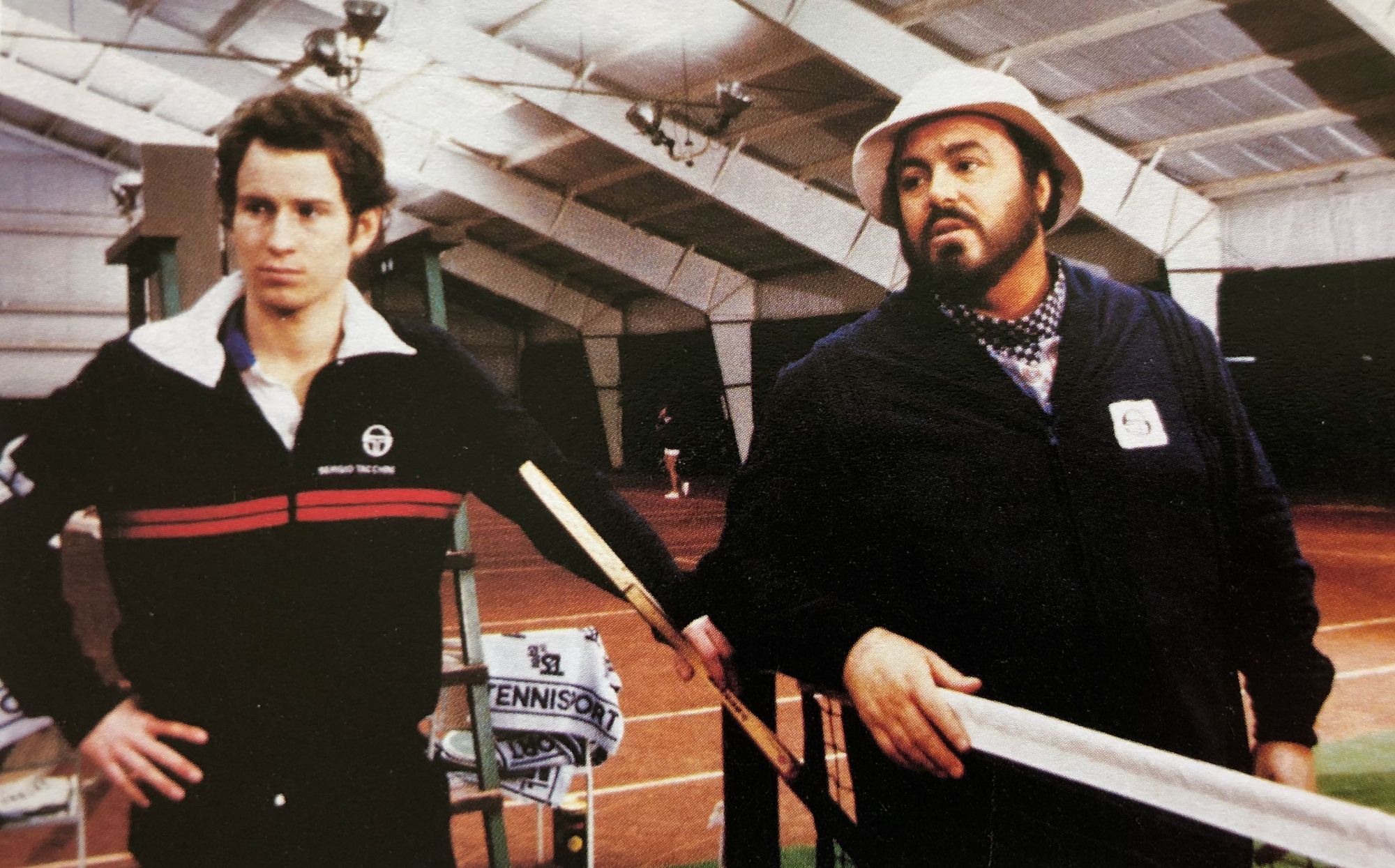

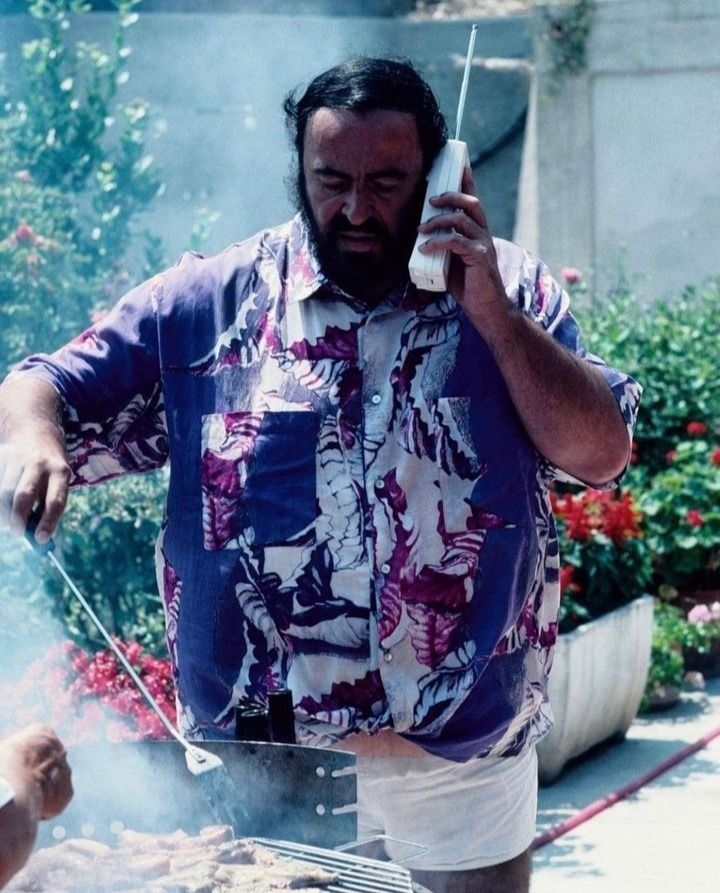

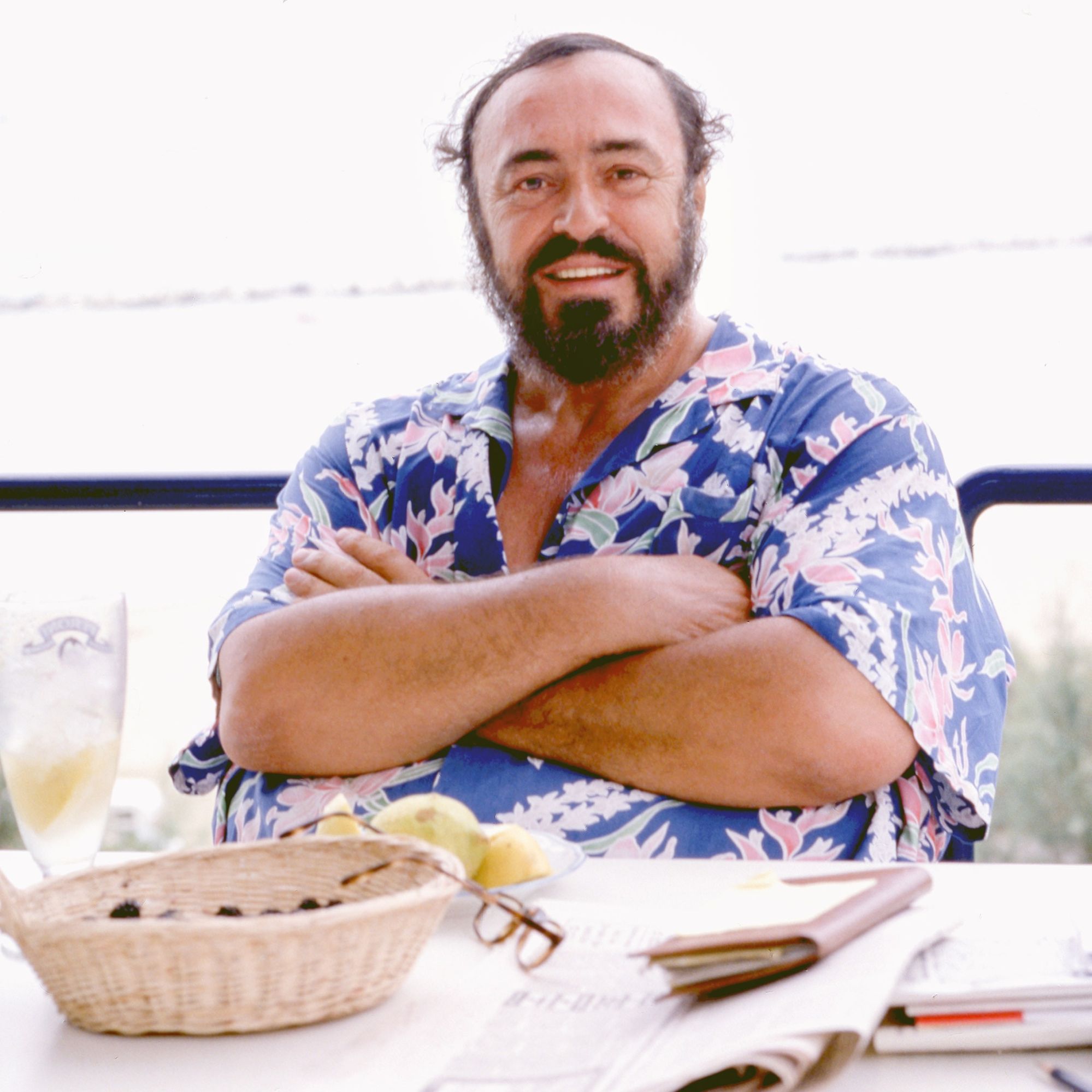

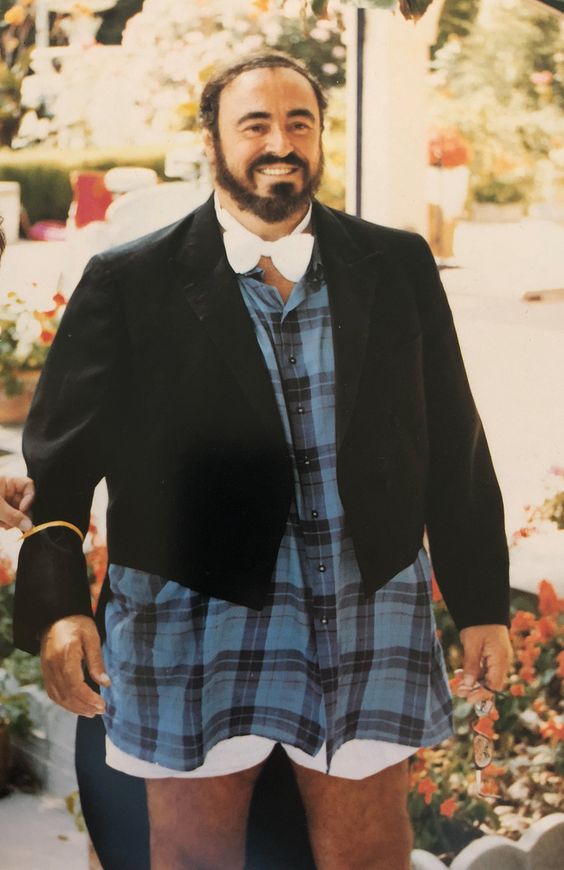

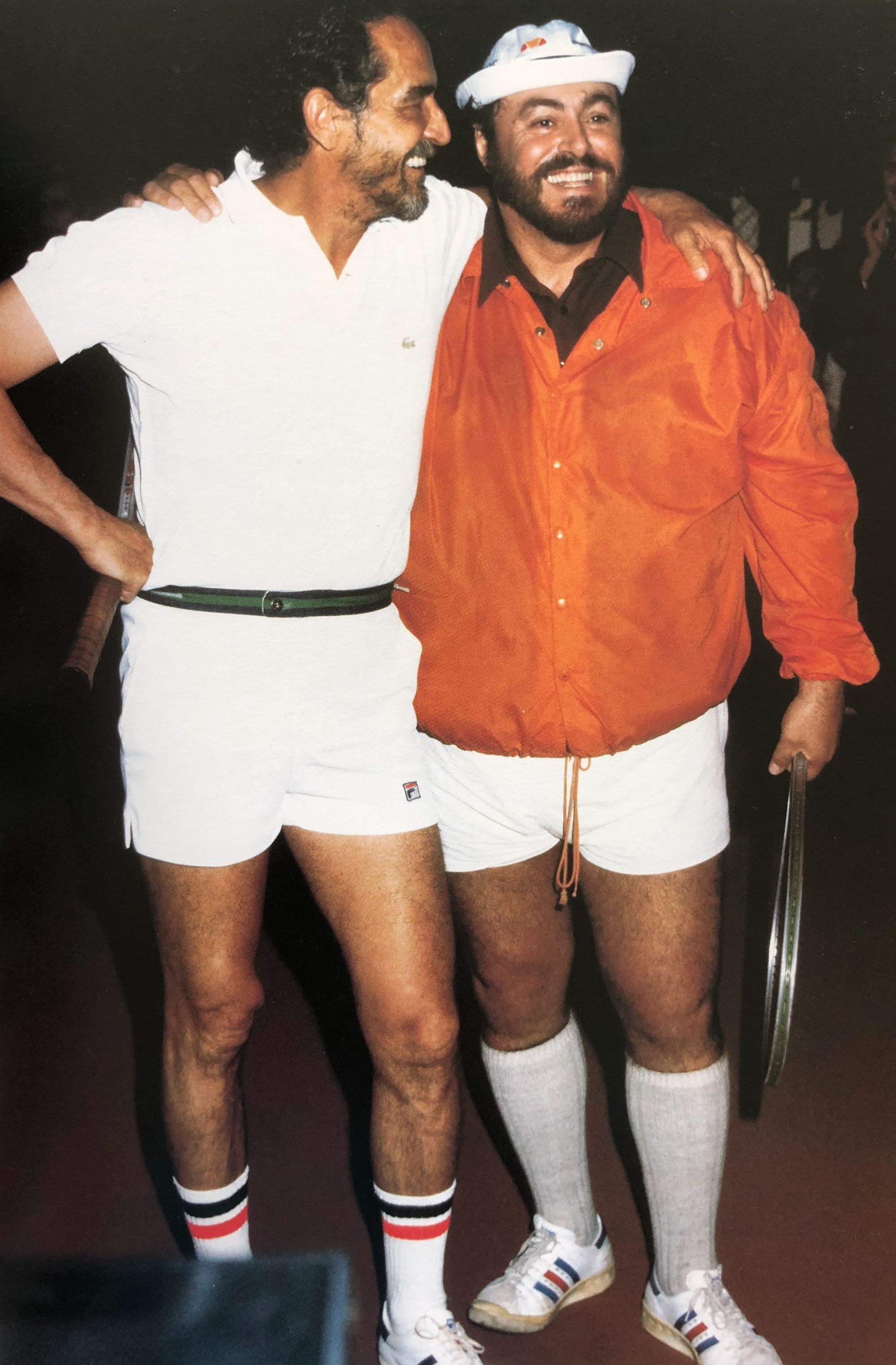

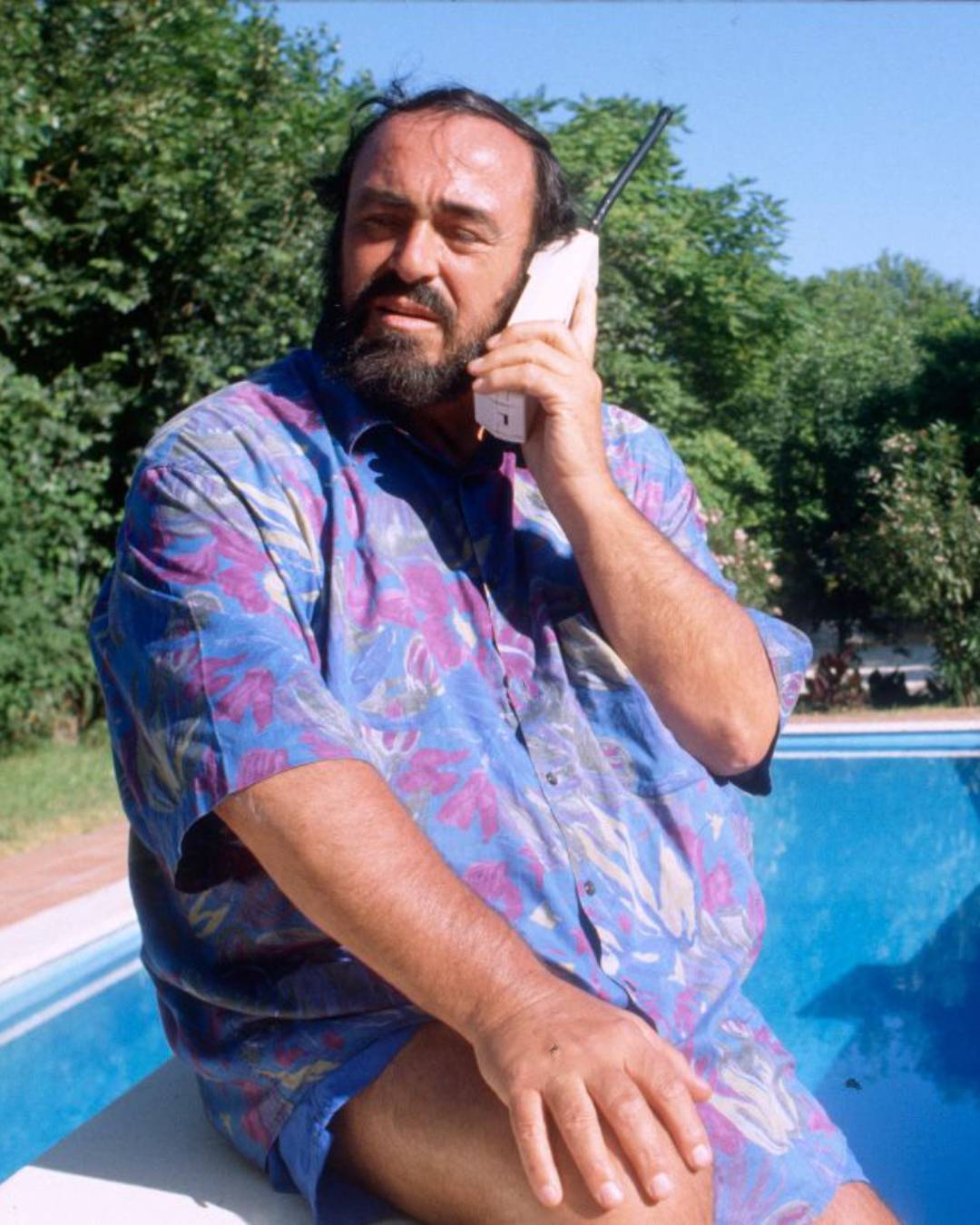

His casual wear, on the other hand, was an anthology of different signifiers that told the story of his personality: the omnipresent scarf identified him as an artist; the thick wool suits in which he was portrayed strolling in nature or in the countryside painted him as a gentleman of the people, as did the wide smiles and affectionate expressions often seen in photographs; the large shirts, with sleeves often rolled up and a pen in the pocket, spoke with the colors of the exuberance of his personality and, with their nonchalance, indicated the practical and active nature of a worker who wants as few hindrances as possible; the occasional red robe testified to refined taste with a touch of flamboyance. That's the point. Offstage, Pavarotti was exactly like any other Italian dad: he often wore a blue tracksuit with white stripes on the sleeves for tennis or horseback riding, loved the practicality of a track jacket, put a napkin in the neckline of his shirt, and sat at the table.

If another opera superstar like Maria Callas presented herself as a regal, almost hieratic figure, absurdly chic even in moments of tranquility, the tenor from Modena cooked live on American talk shows, had himself photographed by Time while swimming in the pool, and was always surrounded by relatives and dinner companions. The only concession to opulence he made was those huge and colorful scarves, almost a residue of the costumes from Rigoletto or Turandot, worn as a king would wear his ermine. His constant joviality did not diminish his popularity around the world, even in the face of his tax problems, from which he was acquitted every time but which followed him for years: in 2000, he had to negotiate a whopping settlement of 25 billion lire, the check for which the tenor himself handed over to the then finance minister Del Turco in front of the press and photographers. After depositing the enormous sum, the tenor managed to joke, «I feel lighter in spirit and not only...» burying a potential debacle with humor. In our country, nothing is forgiven to a politician, everything to a comedian.

How much did style play a part in creating this myth? Maximum and minimum. Minimum because, in his years, it was easier to see Pavarotti on stage or in a tuxedo than in his personal looks, and thus his style emerged from TV programs or photos in magazines but without that impact, as it was a common look at the time and little considered compared to his singing work; maximum because precisely those photos, in the era of the internet, began to circulate again, suggesting a familiar, fun, and very approachable image, often quite detached from the Maestro's stature in the field of opera. What people appreciate about him is the excess and abandon that those photos testify to; even the neglect of many of his outfits has become appreciable. In this sense, if Pavarotti's work belongs to the highest art, his outfits and the appreciation for them are pure post-modern camp. Which of the two Pavarottis will survive longer in collective memory? We hope for both, but perhaps we cheer for the first.