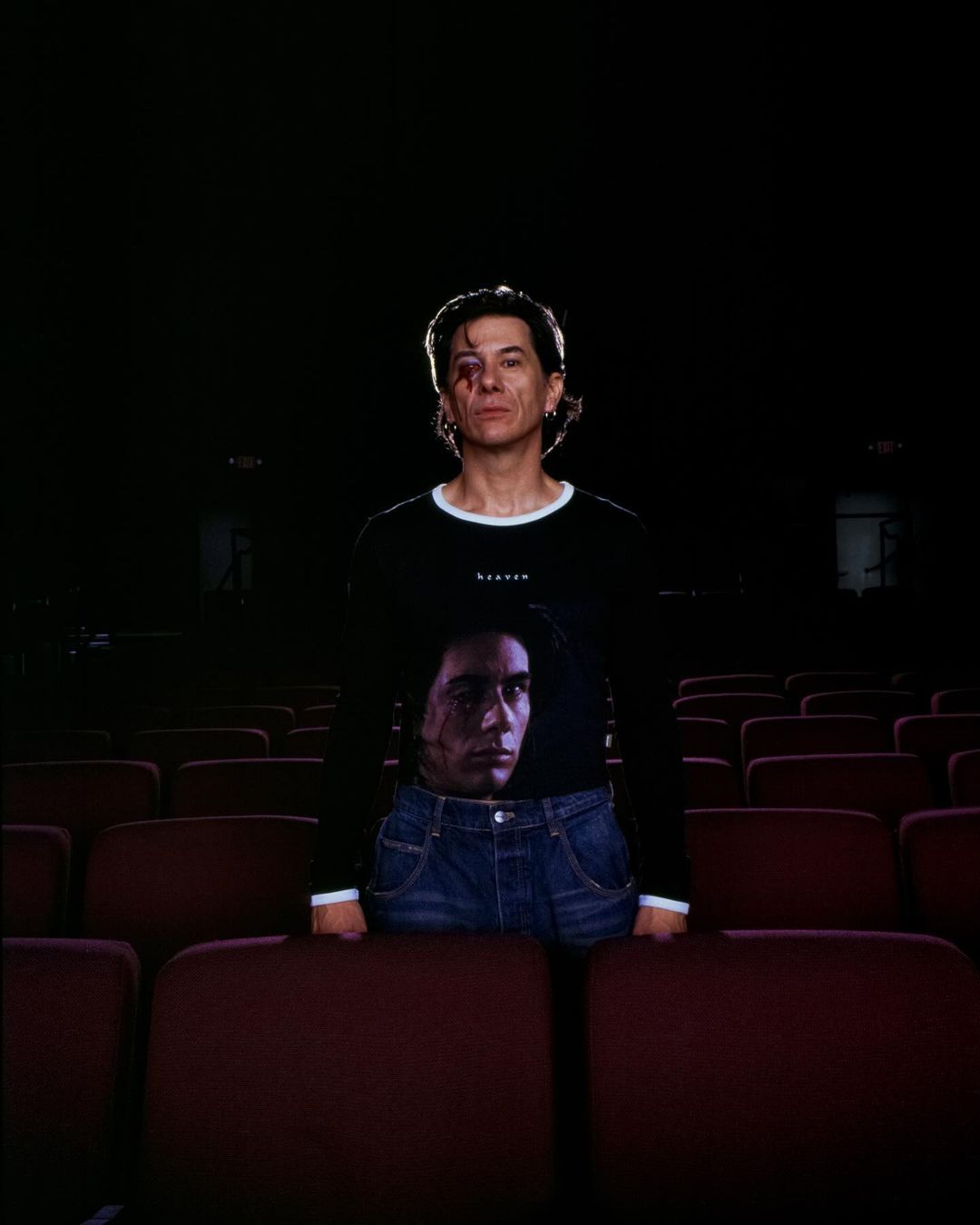

The Heaven by Marc Jacobs collab for Donnie Darko recalls a timeless cult hit «Why are you wearing that stupid man costume?»

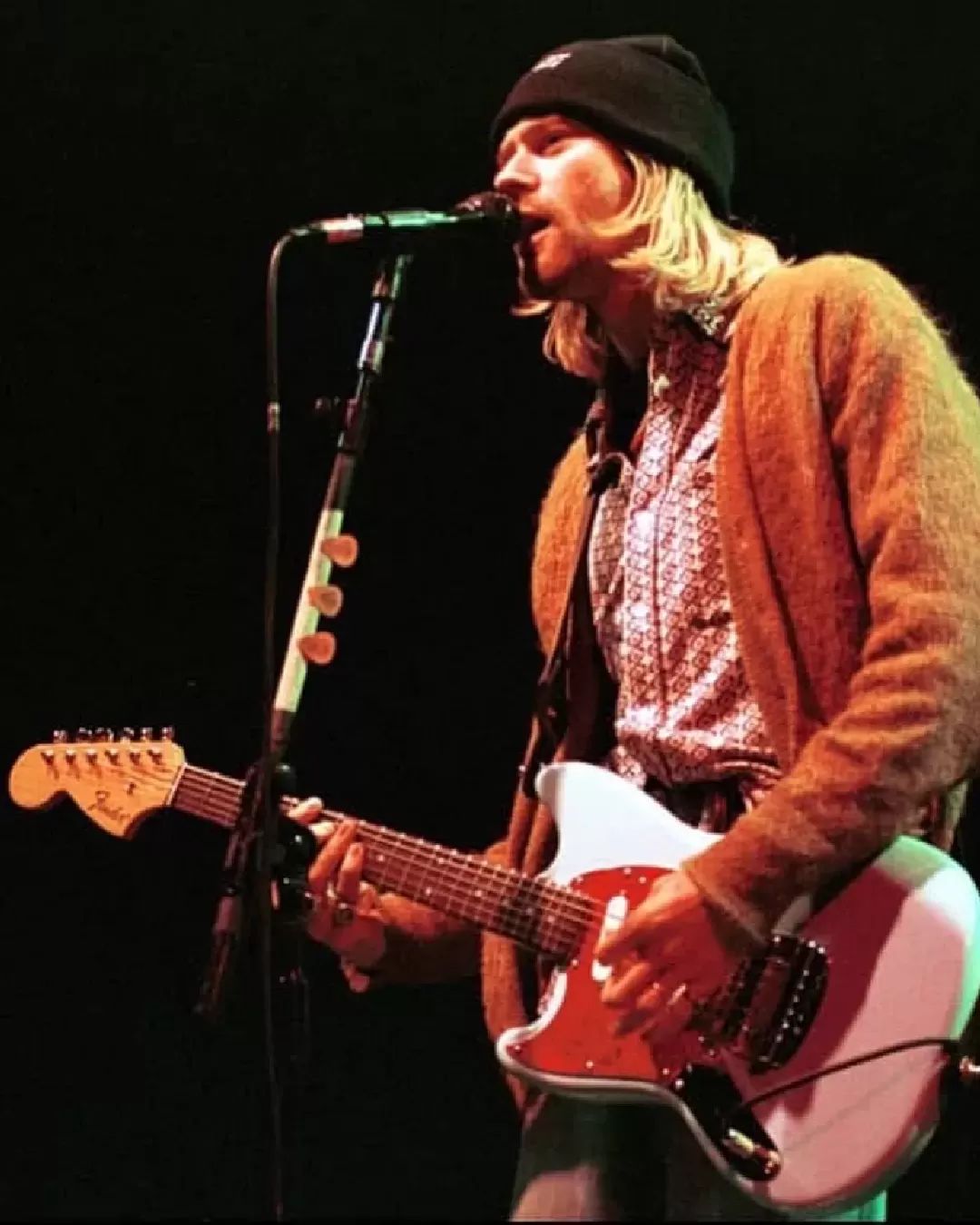

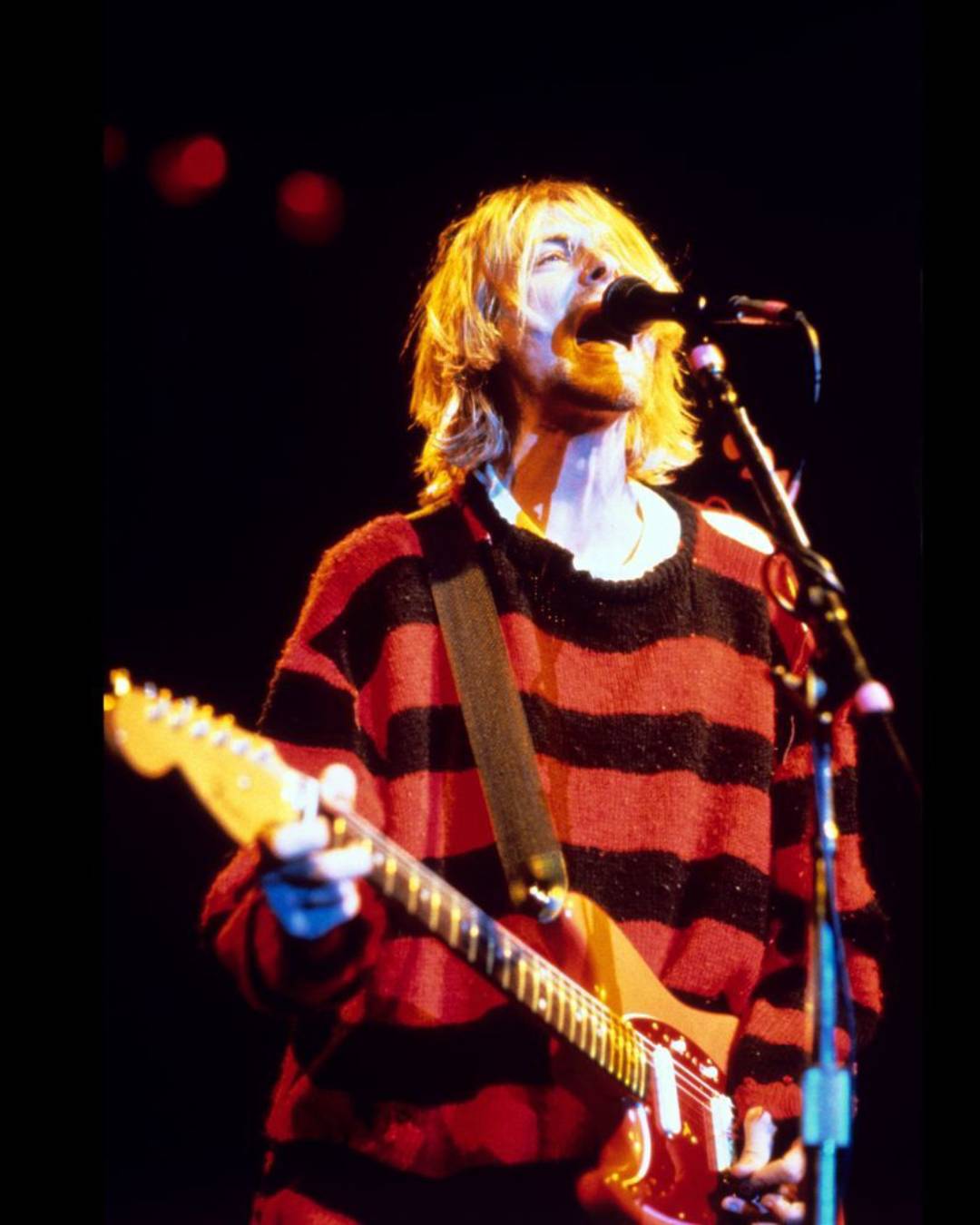

There was a time when the kid who wore black to school, flaunting angry attitudes and a certain love of the macabre, was just the classic freak, one of those 80s archetypes immortalised in John Hughes' The Breakfast Club who inevitably ended up correcting himself by the end of the story. But at the beginning of the 2000s an anti-hero arrived on the scene (and with a very strange film) that metalheads, emo ante-litteram and outcasts of all kinds could look up to: it was Donnie Darko. Starring in a somewhat incomprehensible but aesthetically immaculate film, this sad teenager, prophetic as he was schizophrenic (in the clinical sense of the word), picked up the banner of the angsty character that Kurt Cobain had dropped with his suicide just under a decade earlier. Since then, after a box office failure and a rapid cultural resurgence through video rentals, Donnie Darko not only became a cult film on par with those of Gregg Araki's and Harmony Korine's, but also launched Jake Gyllenhaal's career to unprecedented heights. Now the film has become the star of a Heaven by Marc Jacobs capsule featuring its protagonists (the first time Richard Kelly's film has been explicitly featured in a fashion collection), but the impact the film has had on pop culture, just like its uncanny appeal, is as vast as it is subterranean. During an episode of Actors on Actors, talking to Gyllenhaal, Lady Gaga said: «In the world of music, but also in the world of fashion, Donnie Darko is a religion.»

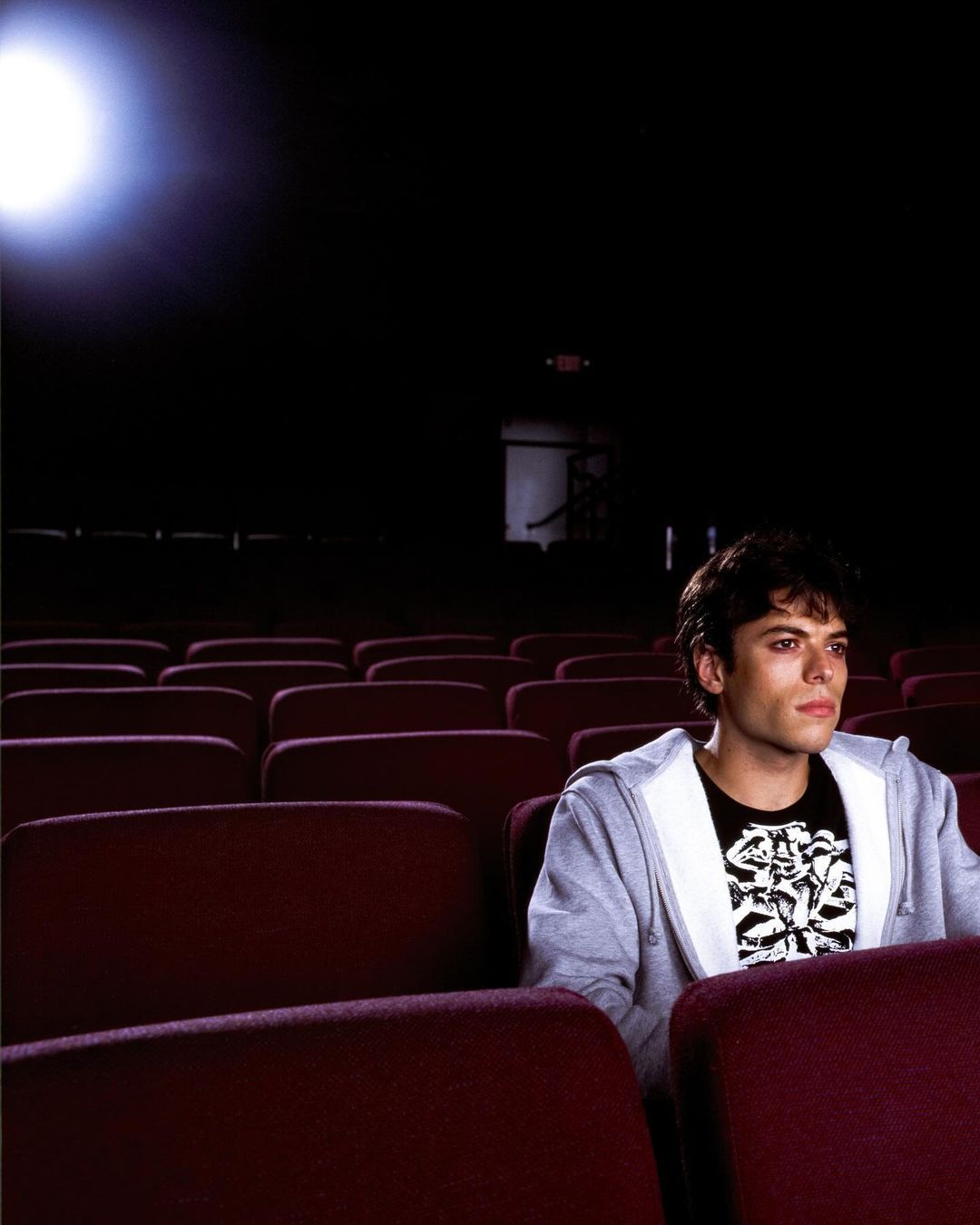

Now, if in the fashion world the most explicit reference to the film one can think of is the Skeleton Intarsia Sweater created by Anthony Vaccarello for Saint Laurent's FW18 (the garment did not appear on the catwalk but remains to this day one of the most iconic pieces, together with Stefano Pilati's FW12 Razor Blade Sweater), the real contribution of the film was to give a definitive codification to the teen goth archetype. Thanks to Donnie Darko, the melancholic and idiosyncratic musical atmosphere of the youth discomfort of those years was freed from the paramilitary paraphernalia of metal, from the flannels and ripped jeans of grunge, to be placed in a suburban dimension where a grey hoodie is worn over a Halloween skeleton costume. The rigour of school uniforms is only the extension of an exclusively black and white wardrobe in which the gothic soul of someone who looks normal but is not, where a white shirt echoes fantasies of the darkest Byronic romanticism, is hidden. Released in 2001, Kelly's film became the forerunner of the alternative wave that dominated the entire decade, sending shocks through pop culture that continue to be felt. Even today, a pop star such as Phoebe Bridgers dresses as Donnie Darko and the film's soundtrack is considered responsible for the sad cover phenomenon - Gary Jules' Mad World remains a far more iconic track than the original by Tears for Fears. Some, more critically, suggest that the film is the precursor or even the remote initiator of the modern obsession that new generations have with exploring and understanding mental illness, but in truth it was a participatory reflection of it.

If American Beauty and Ice Storm were revelatory products of the shocking nature of the traditional family narrated from the parents' point of view, Donnie Darko was the first and most bizarre film to portray the disconnect between society's laughing façade and the more frightening abyss of madness through the lens of youthful dysfunction. Over the years, Richard Kelly has claimed that the film is all about time travel, but it's hard to believe him: the film is about mental illness, not only with a protagonist who displays many of the classic symptoms of schizophrenia, but with a host of side characters who tell us how our grandmothers, parents, classmates and school counsellors are all prey to personal demons that are perhaps more manageable but no less obscure - the entire society depicted in the film, in fact, seems deeply ill. From a certain point of view, that of culture-as-manufacture, arriving at the very dawn of Internet culture, the film became a little factory of memes and aphorisms repeated like a tam-tam through the first MSN blogs, Tumblr and Flickr and so on. It was one of the first films of that era to gain its cult status thanks to the Internet phenomenon of the early 2000s. So strong was the effect of the Internet that even today many fans of the film say they love the film not for the frankly incomprehensible plot, but for the world it builds for its characters, for the way it manages to transform the classic American small town into a kind of black fairy tale, a mirror of the Millennial malaise that 1980s positivism (the film is set in October 1988) was no longer able to explain.