Alexander McQueen's new creative director is yet another white man Despite good intentions, fashion has a problem with inclusiveness

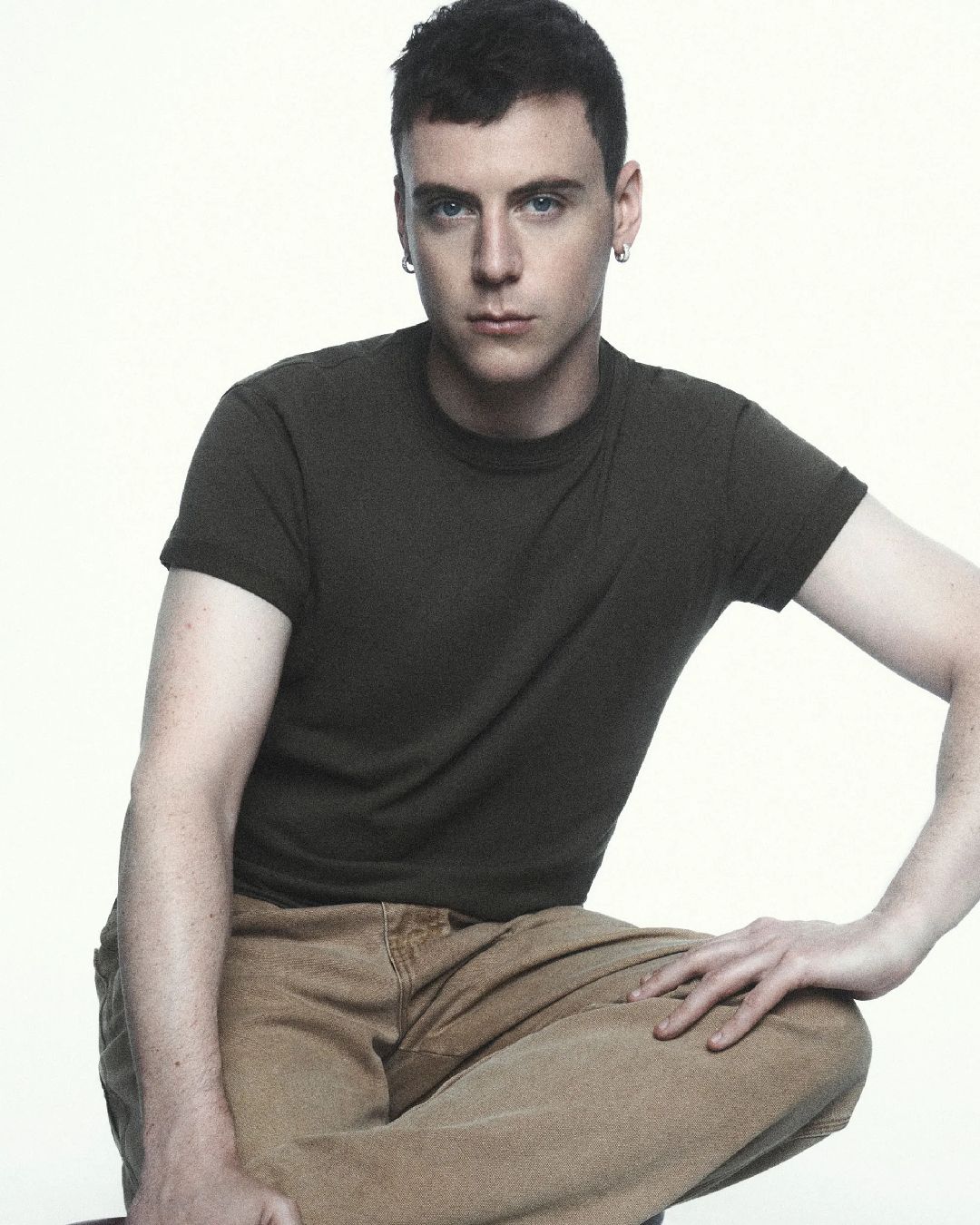

The new artistic director of Alexander McQueen, the brand that this week had to bid a final farewell to Sarah Burton, is Irishman Sean McGirr, former head of menswear at JW Anderson. McGirr is an alumnus of Central Saint Martins, retains a passion for photography and London street style, has previously worked in the ateliers of Dries Van Noten and Burberry and has written for the trend forecasting agency Stylus. Although McGirr's is an established talent, given the references that appear on his CV, his first projects at the helm of McQueen will see him confront an audience of sceptics, disappointed by Kering's choice to bring another white man to the top of the artistic direction of a historic maison. On the eve of Fashion Month, a month before Kering made McGirr's appointment public, all users of High Fashion Twitter had begun to share their fish on the names of emerging designers who might have been considered for the post. Many had set their sights on Dilara Findikoglu, the Anglo-Turkish designer responsible for looks similar in historical references to those of Lee McQueen, others had predicted the handover to a white man, as the latest decisions of the other luxury conglomerates suggested, turning out in retrospect to be right. Some time ago we extolled the need for greater female representation at the top of fashion, and today we find ourselves reiterating the same concept.

creative directors of brands under fashion conglomerates:

— chloe (@chloeikennedy) October 3, 2023

LVMH:

- 22% white women

- 16% men of color

- 0% women of color

Kering:

- 0% women and/or poc

Puig:

- 0% women and/or poc

* one genderfluid cd: harrison reed

Richemont:

- 0% women and/or poc (as of gabriela hearst exit)

During the first week of Fashion Month, the Vogue Business platform published the results of the Success in Fashion survey - who has the right to succeed in fashion? Today this question has an obvious and disappointing answer: white men. With McGirr's new appointment as artistic director of McQueen and Gabriela Hearst's departure at Chloé, the artistic portfolios of Kering and Richemont have lost their only pink quotas. As of now, Francois Pinault's group and Jerome Lambert's group join the list of luxury companies whose creative directors are all white men, the ultimate proof of the huge steps backwards taken by the haute couture leadership over the past year and the ambiguous message that continues to be put forward by the industry's media, a narrative of inclusion that certainly does not correspond to the facts. Fashion is a hobby for women, but a job for men? According to last month's findings, yes. In the very Vogue Business survey, sexism and racism were brought up as the main reasons for the lack of representation in the fashion industry. 52% of the respondents said that their ethnicity had negatively influenced their career, while some women said that the climate of camaraderie usually established between men in the workplace had severely impacted their career path. Similarly, repeated occurrences of sexism made them feel inadequate, forcing them away from an ideal position for career advancement. A month before McGirr's appointment was announced, the survey perfectly explained why journalists and fashionistas are taking to social media these days to highlight the lack of minorities in art direction, pointing out how the portrait of contemporary fashion that we see on the catwalk and in advertising campaigns still does not match the one that lurks in the ateliers and business offices.

@newestcool Sarah Burton hugging Anna Wintour, Cate Blanchett & Edward Enninful after taking her bow for her final @Alexander McQueen show #NewestCool #sarahburton #alexandermcqueenss24 #ss2024 #spring2024 #springsummer2024 #ss24 #edwardenninful #annawintour #cateblanchett original sound - nixra6

The problem is not the lack of talent of the newly elected artistic directors, nor that of women or BIPOC people in the fashion industry, but the opportunity gap that marginalised groups still have to contend with, in order to reach the same level as their privileged counterparts. The null percentage of minorities at the helm of the artistic direction of the Kering and Richemont groups shows that there are still barriers to be broken down in the system, as the inclusive casting of a campaign does not automatically guarantee the diversity of the internal structure that is promoting it. Governments, fashion councils, and the CEOs of the conglomerates themselves must do more, they must continue to choose talent like McGirr but remember that in the hyper-competitive marathon that is the fashion industry, everyone has a different starting point. As long as the opportunity to work alongside Pierpaolo Piccioli and Jonathan Anderson is not available to women and BIPOC people in the same way as it has been for the newly elected to lead Gucci and Alexander McQueen, the appointment by a luxury giant of a white male creative director will continue to be an anachronistic and counterproductive choice.

If fashion is praised today as one of the most diverse sectors in the world of the arts, it is thanks to the minorities who have entered the system, not because of those from above applauding their tenacity. Proof of this phenomenon are creatives such as stylist Law Roach and designer Tremaine Emory - despite the fact that they themselves have had to retire from the scene, tired of an industry still succumbing to systemic racism - or the indisputable talents Wales Bonner and Martine Rose. The privilege of those who now find themselves at the helm of the world's most famous luxury fashion houses is obvious, it will continue to be so in the years to come, and the only ones who can actually change the system are themselves part of the problem. The Vogue Business survey and the recent appointments of luxury creative directors say that only men can succeed in fashion, but the talent and perseverance with which minorities continue to impress the fashion industry prove otherwise.