Men's fashion according to Alexander McQueen The forgotten history of menswear created by fashion's enfant terrible

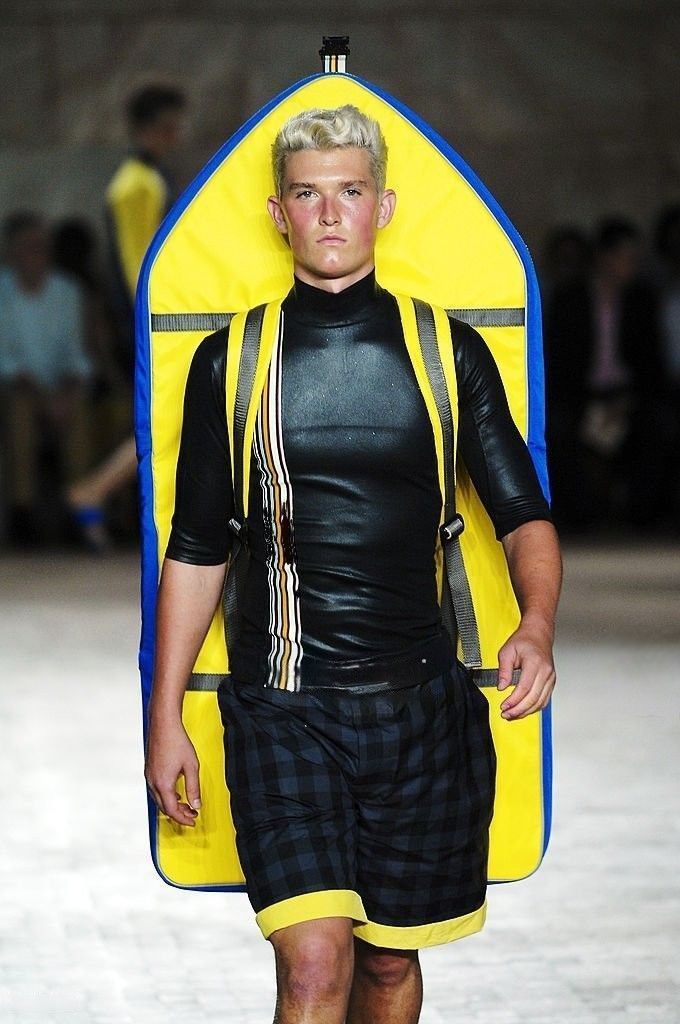

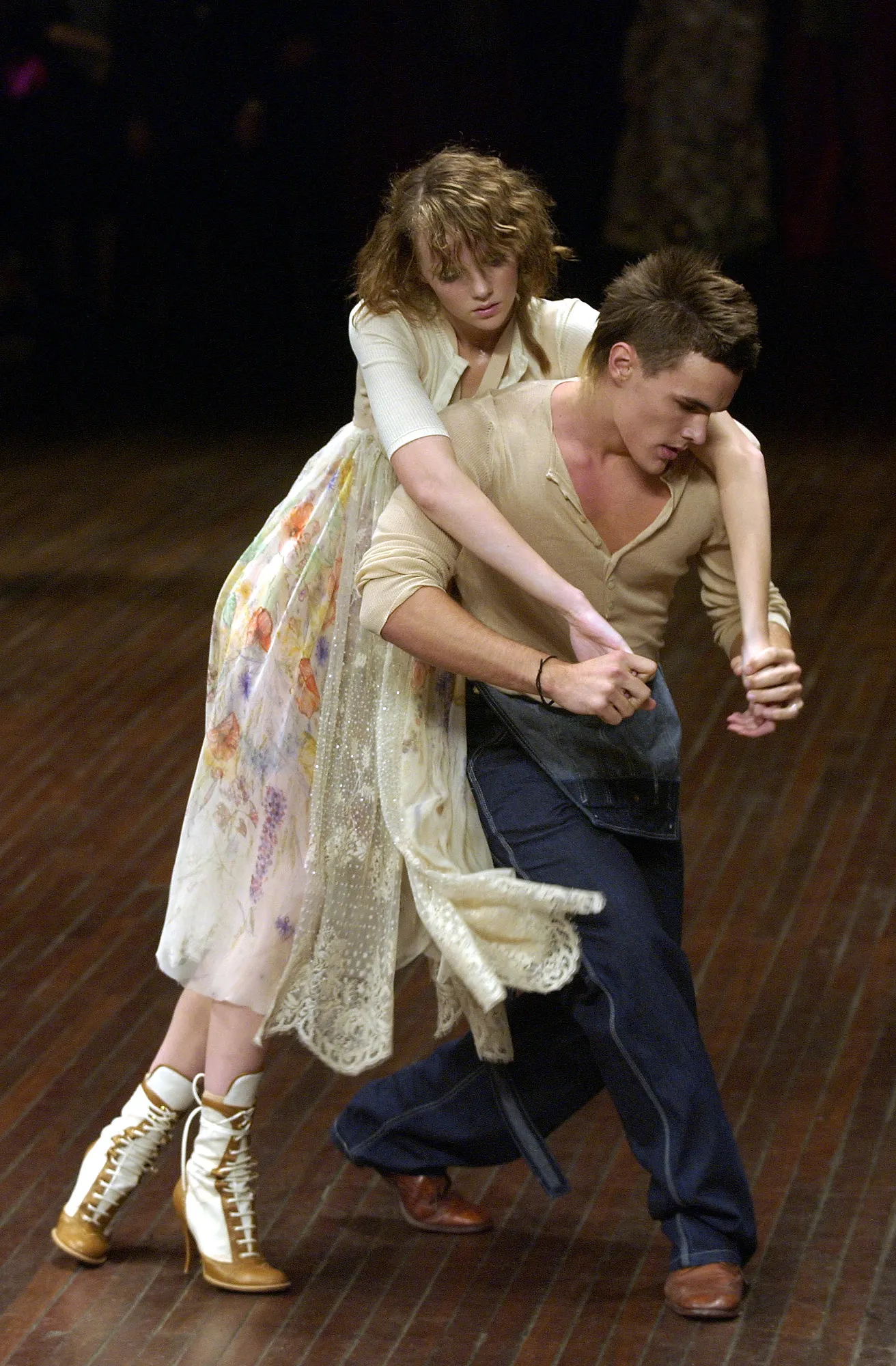

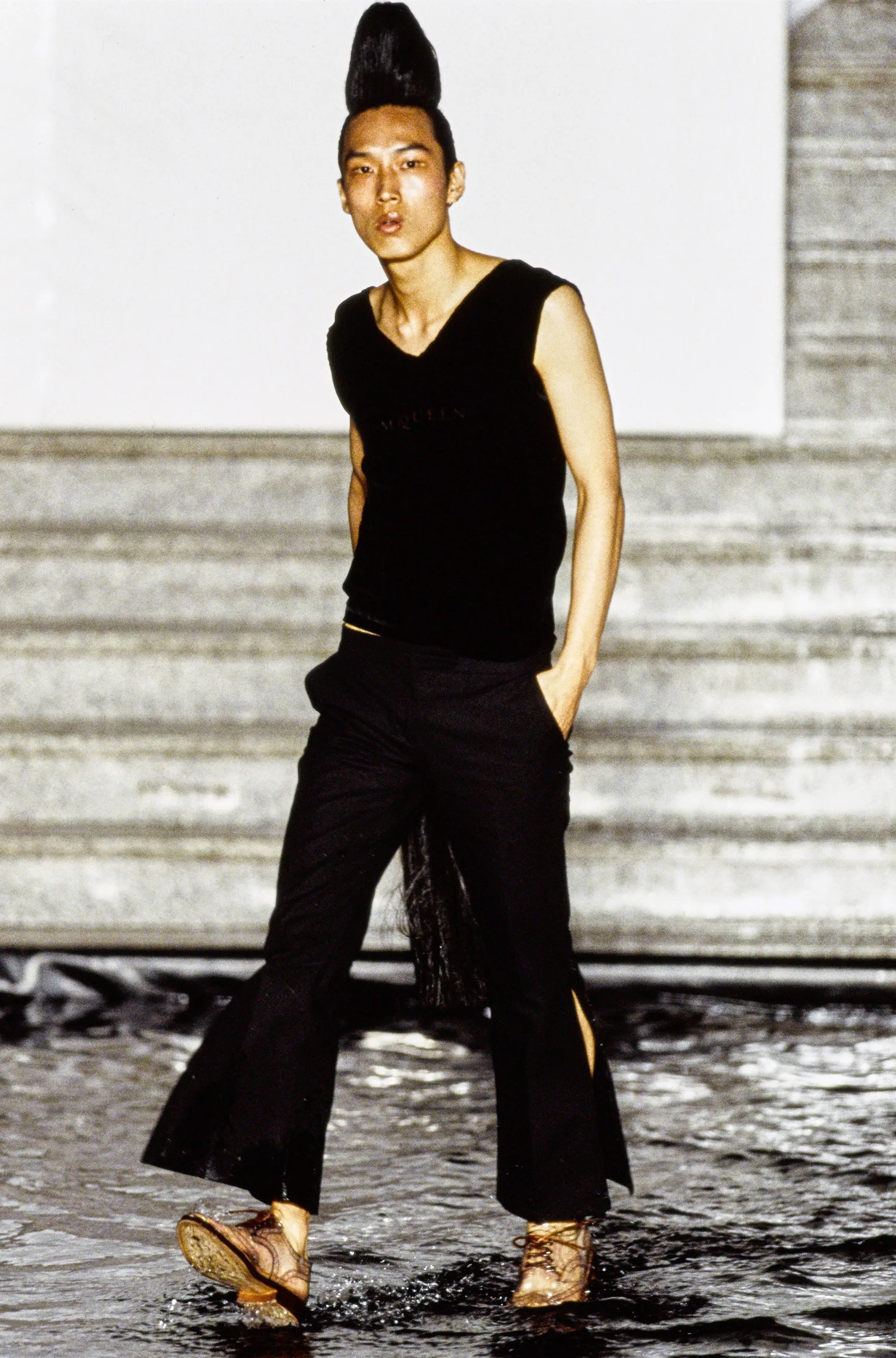

«Menswear is about subtlety. It's about good style and good taste», Lee McQueen once said. Words frankly too vague to represent an entire poetics. If the British designer wanted people to be scared of the women he dressed, the same cannot be said of men - a category for which he rather wanted to «demolish the rules but to keep the tradition» and which, at least for the collections from '96 to '98, in which there was a minority of male looks, were almost an extension of the much more daring womanswear concepts. And even when McQueen officially launched a proper menswear line in 2004, setting up residence at Milan Fashion Week, everyone's attention remained fixed on the women's collections. It was after the brand reached considerable stature, and after McQueen's own death in February 2010, that the two lines, men's and women's, settled on a more common and commercial lingua franca - before then, McQueen's 'canonical' collections were still only considered women's. Yet, McQueen had cut his teeth among the discerning tailors of Savile Row, Anderson & Sheppard and Gieves & Hawkes, who even produced suits for the men of the royal family (McQueen once recounted having sewn the phrase 'I am a cunt' into the lining of a jacket of the current King Charles III) and then modelled theatrical costumes in the tailor's shop Angels & Bermans. And it is clear that while women's clothing was for him an unprecedented field of artistic experimentation as well as a form of escapism, men's clothing represented a more directly biographical project, anchored in reality, subject like everything to «the fragility of romance».

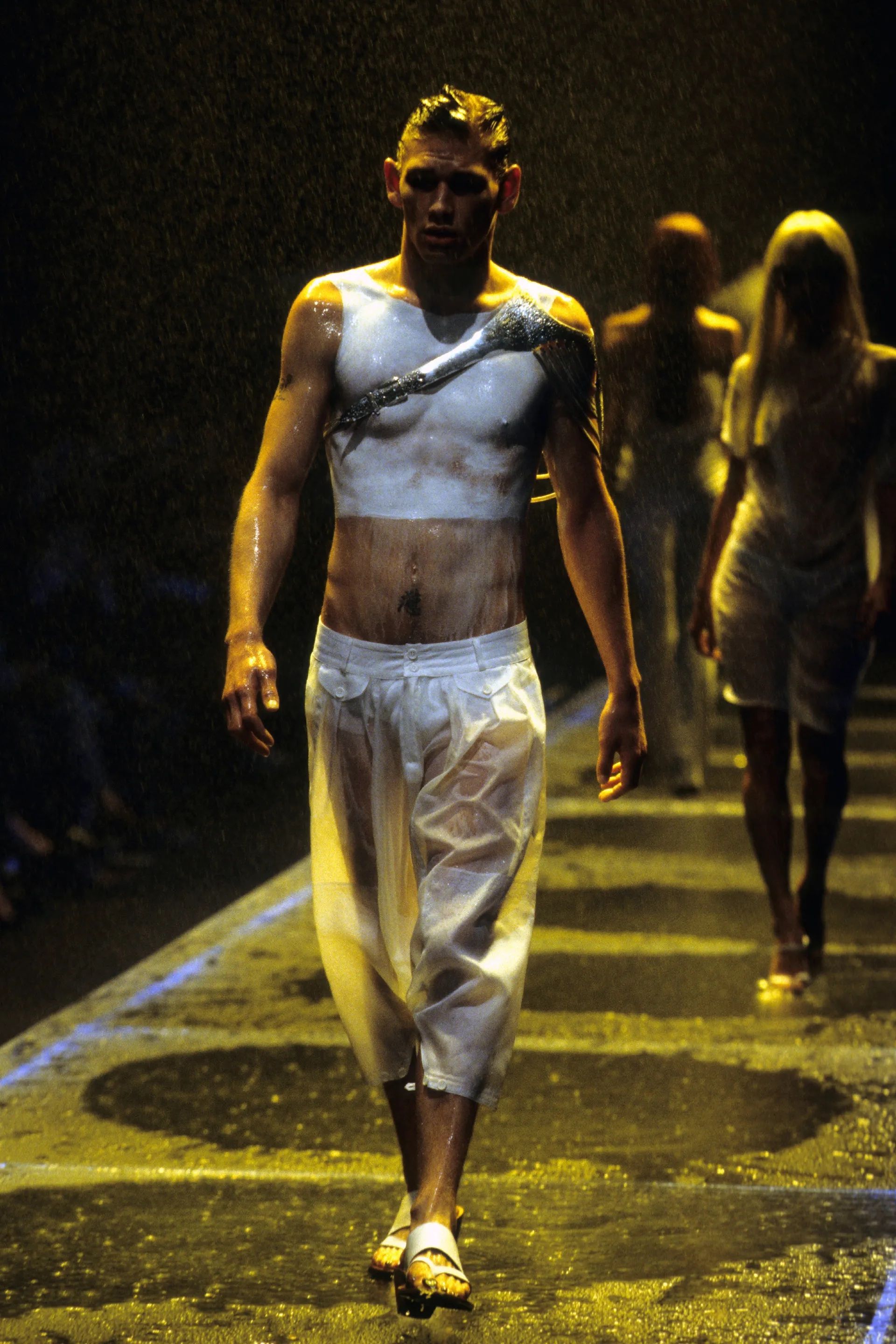

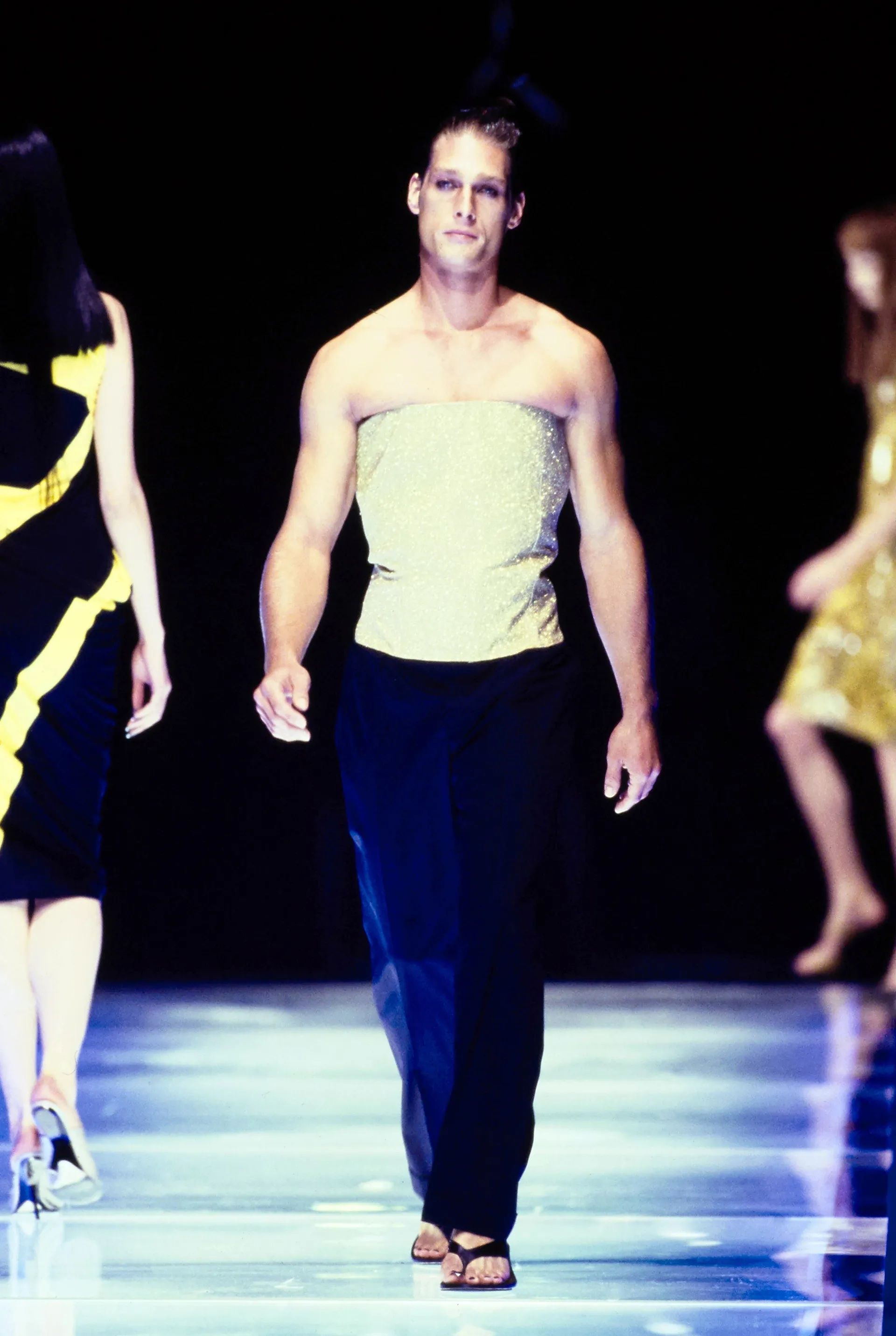

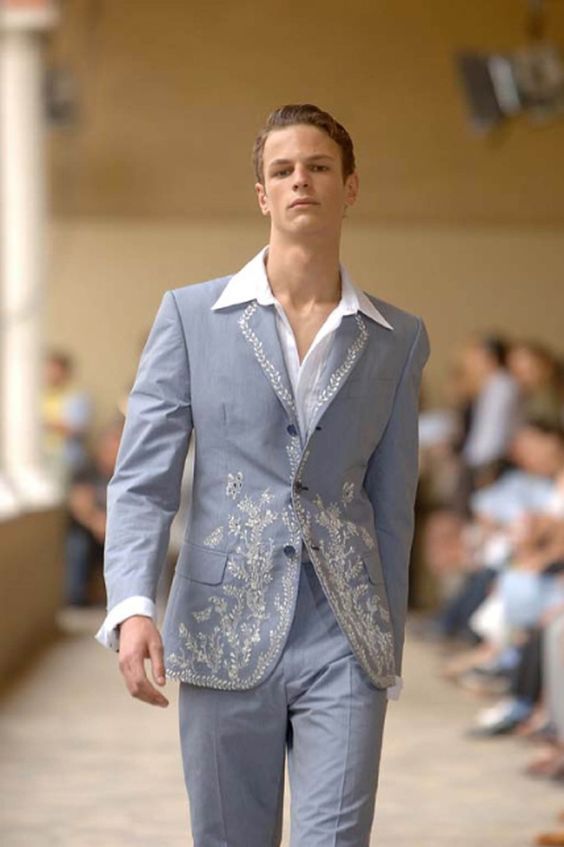

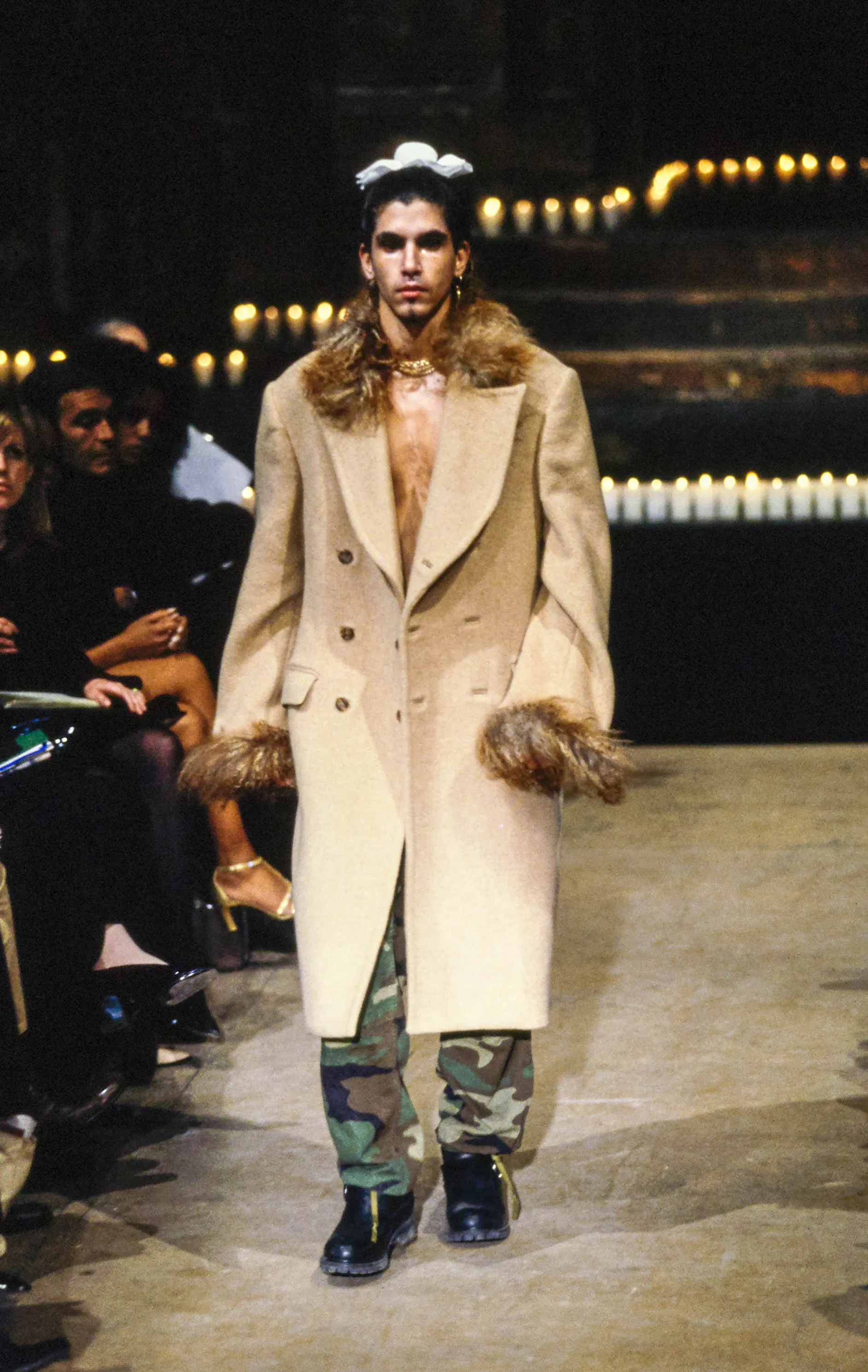

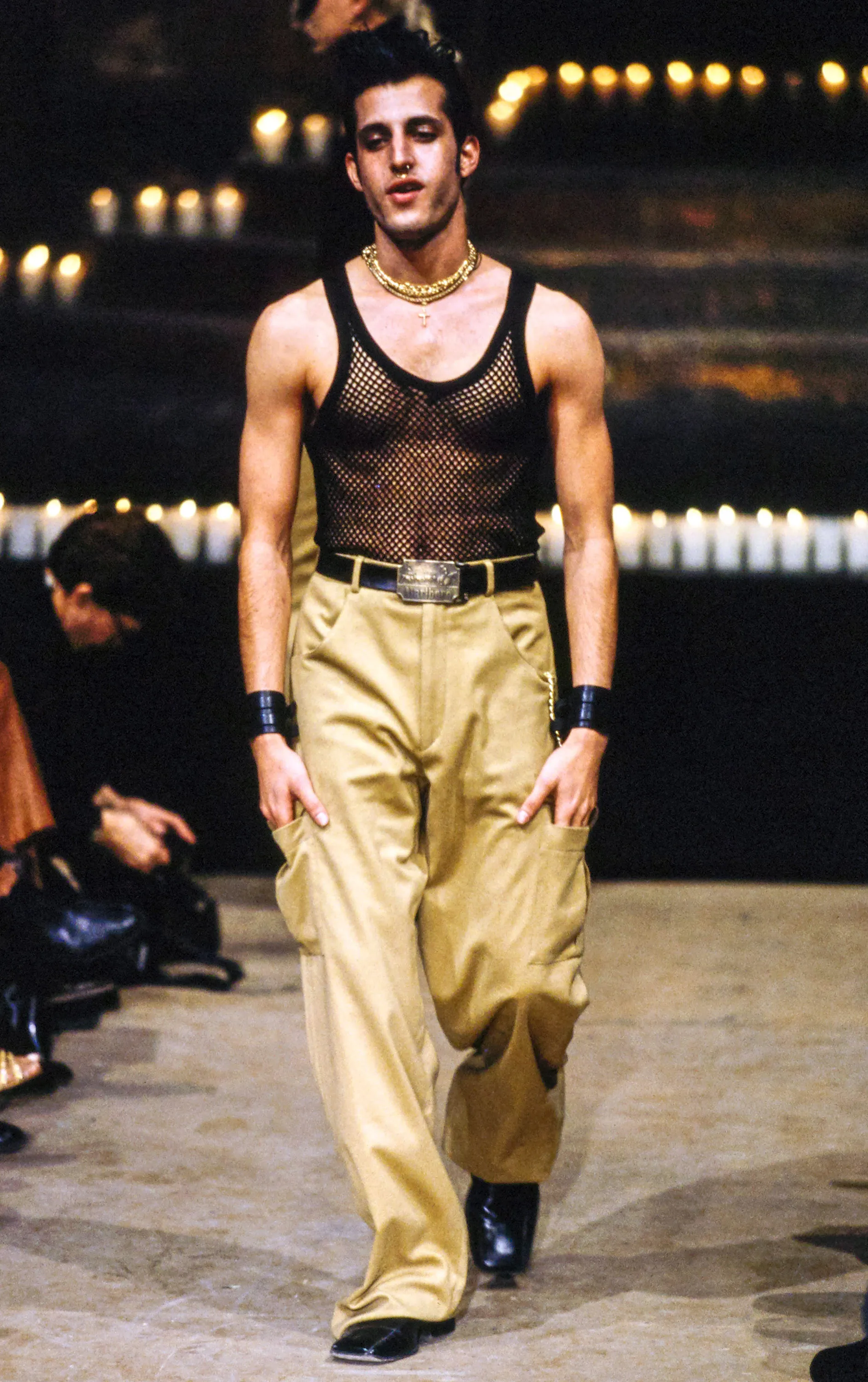

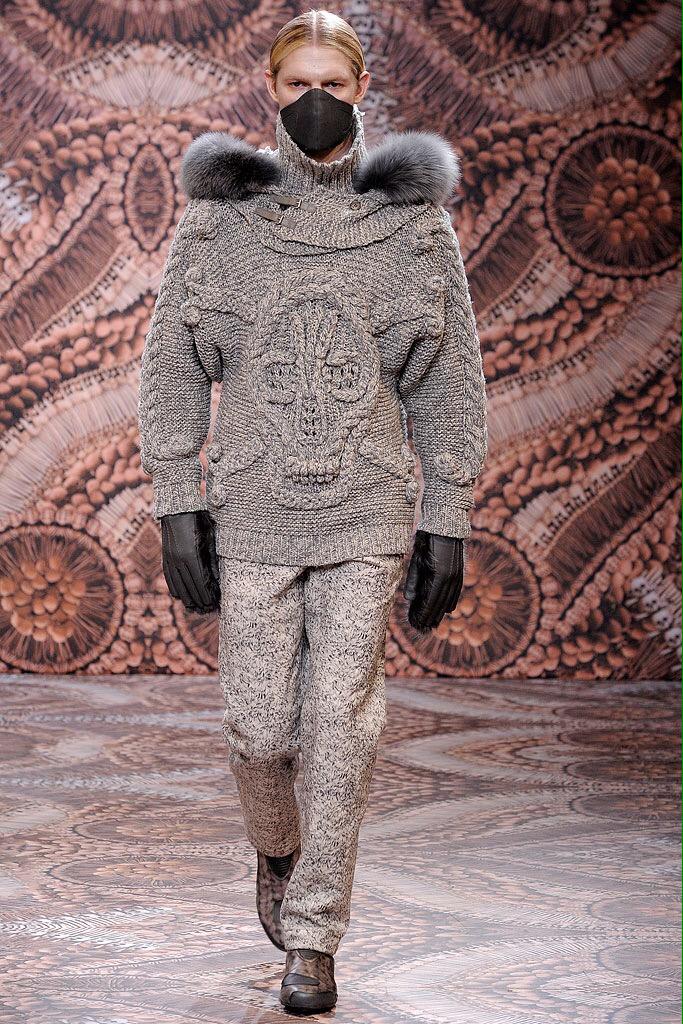

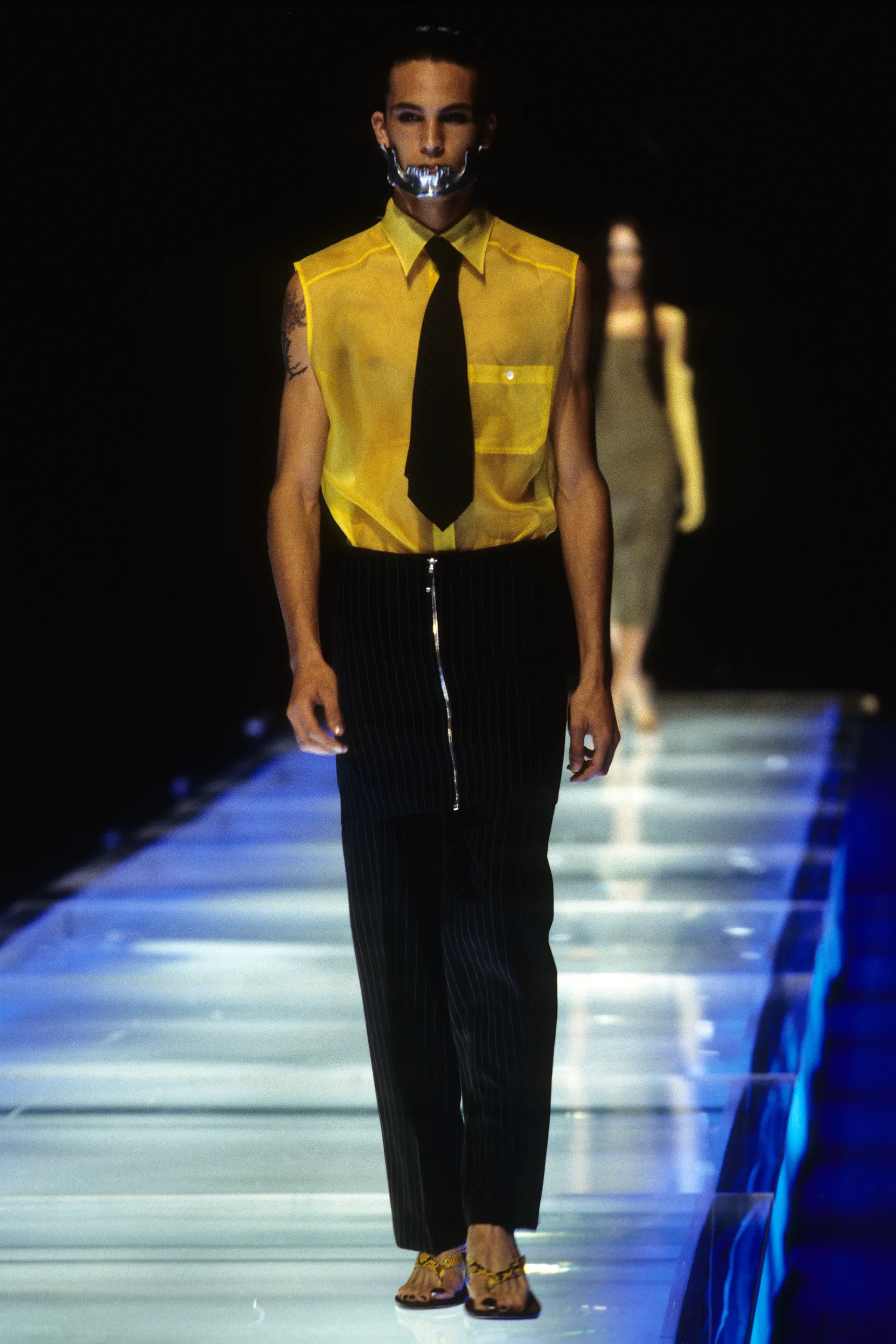

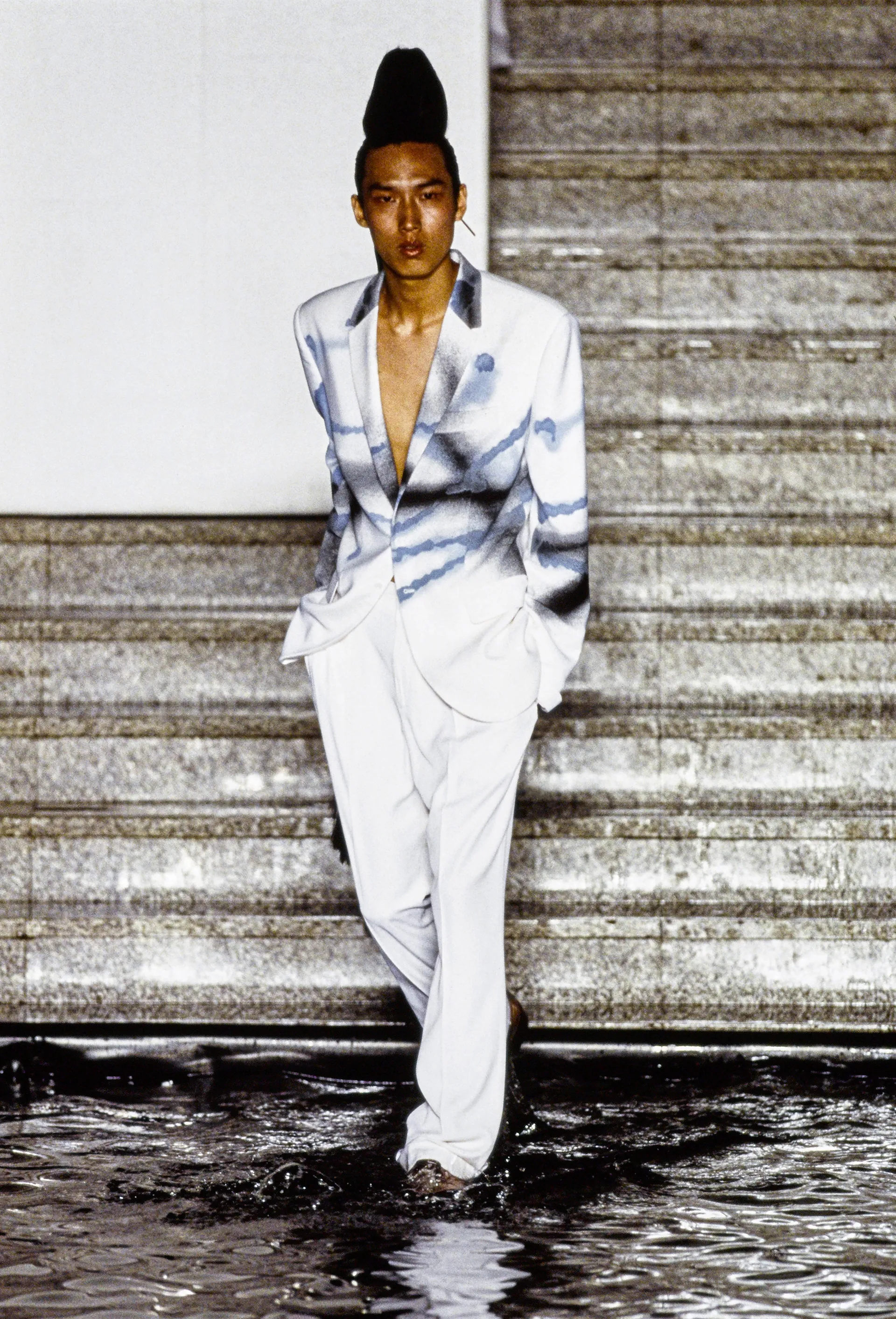

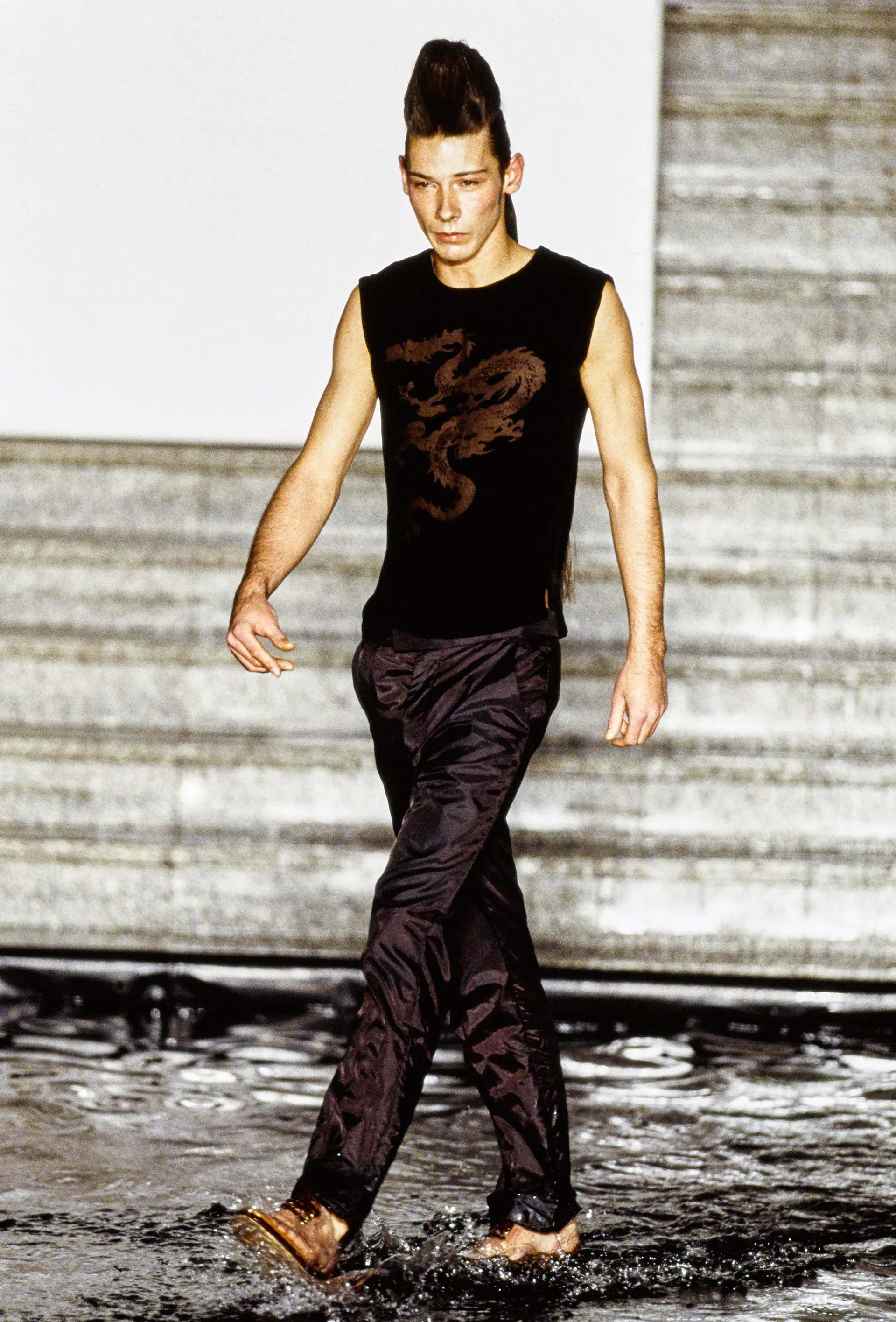

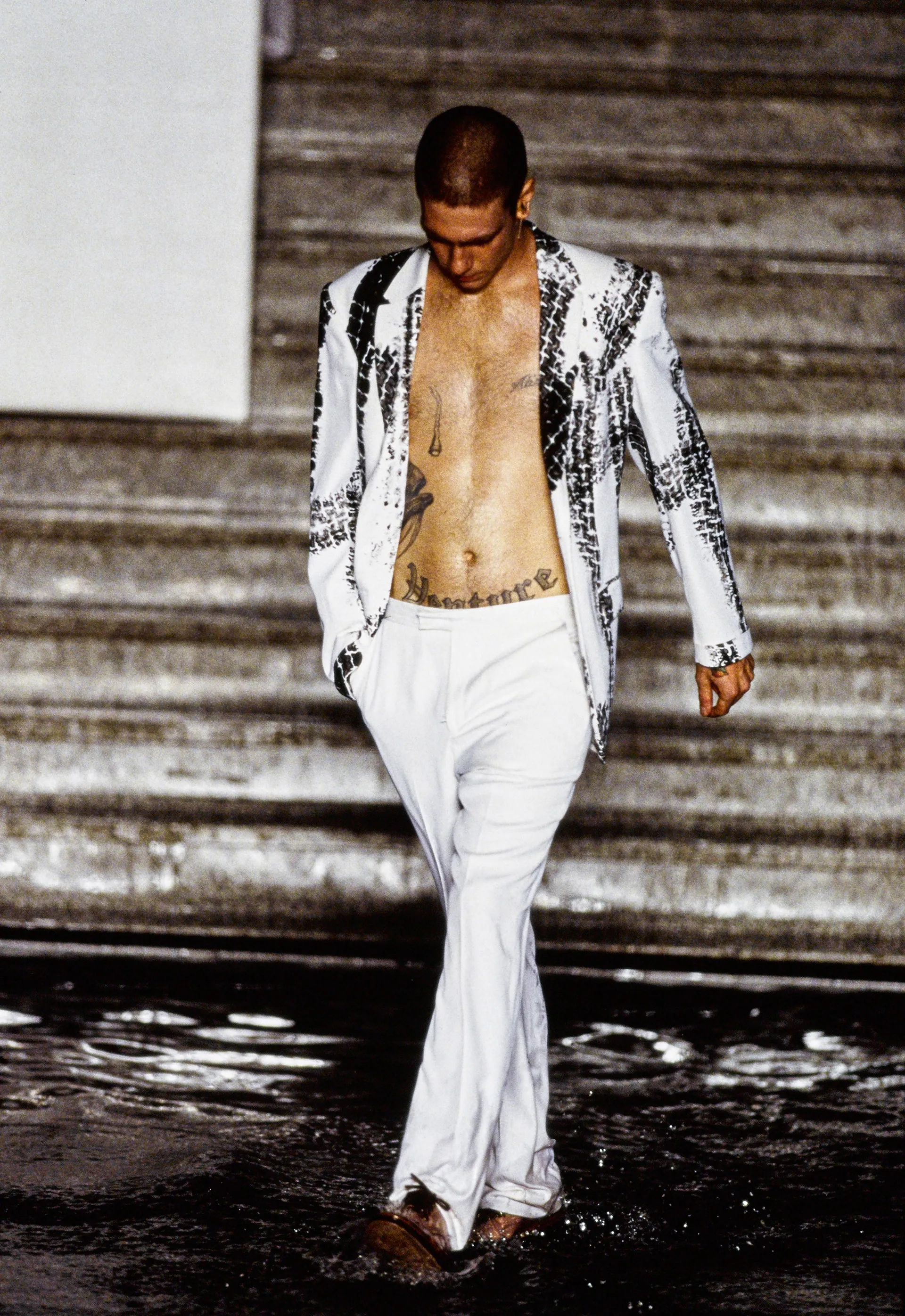

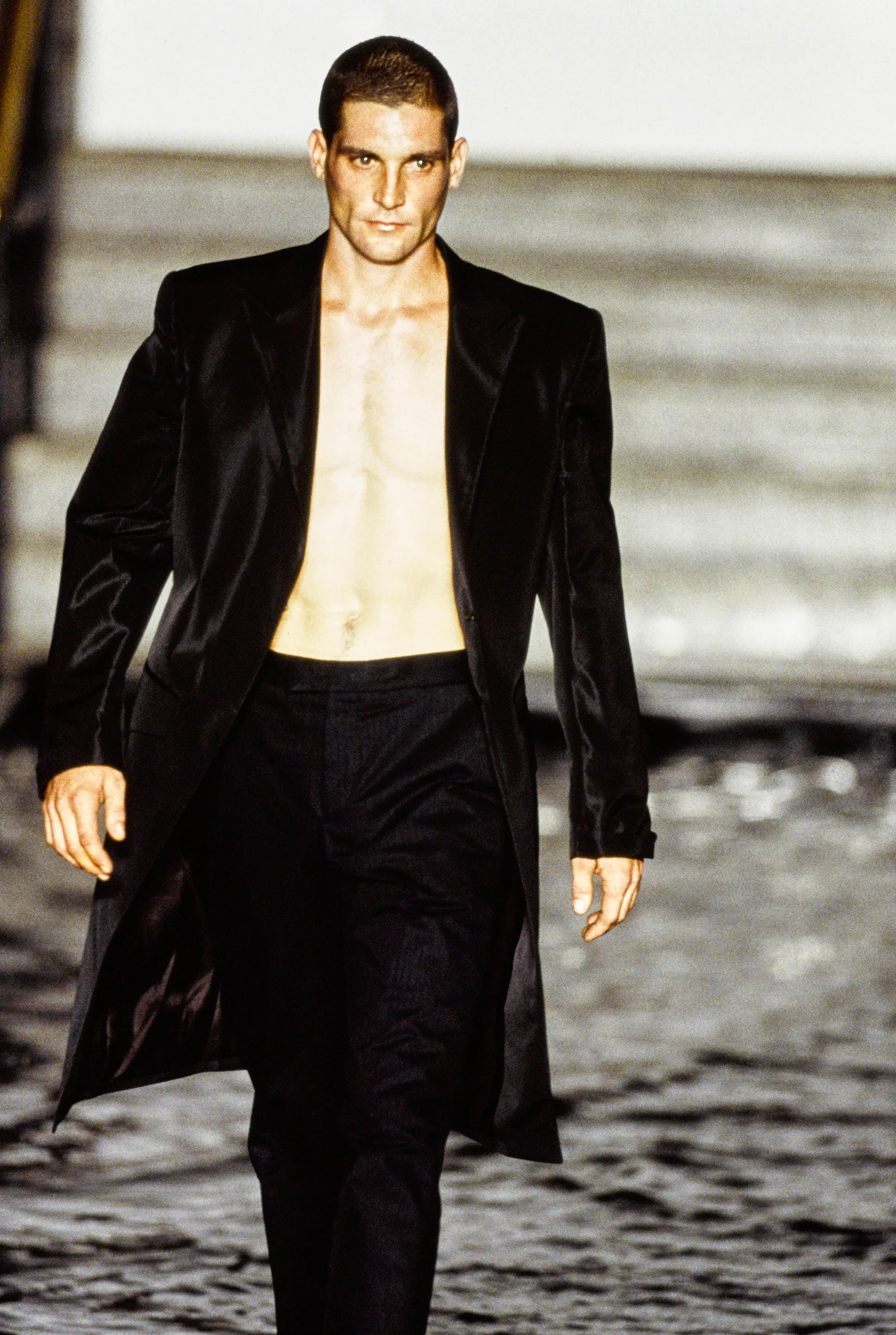

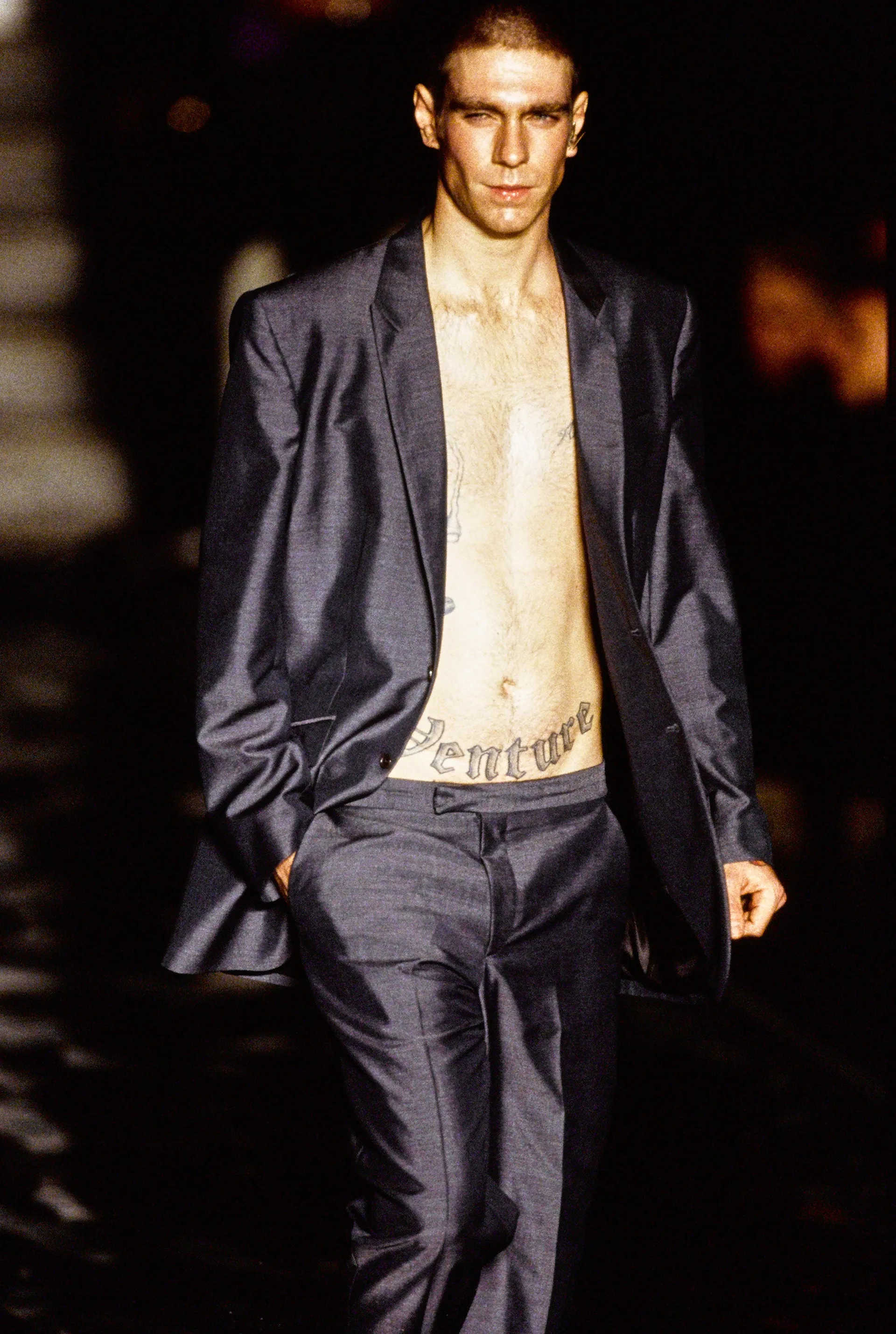

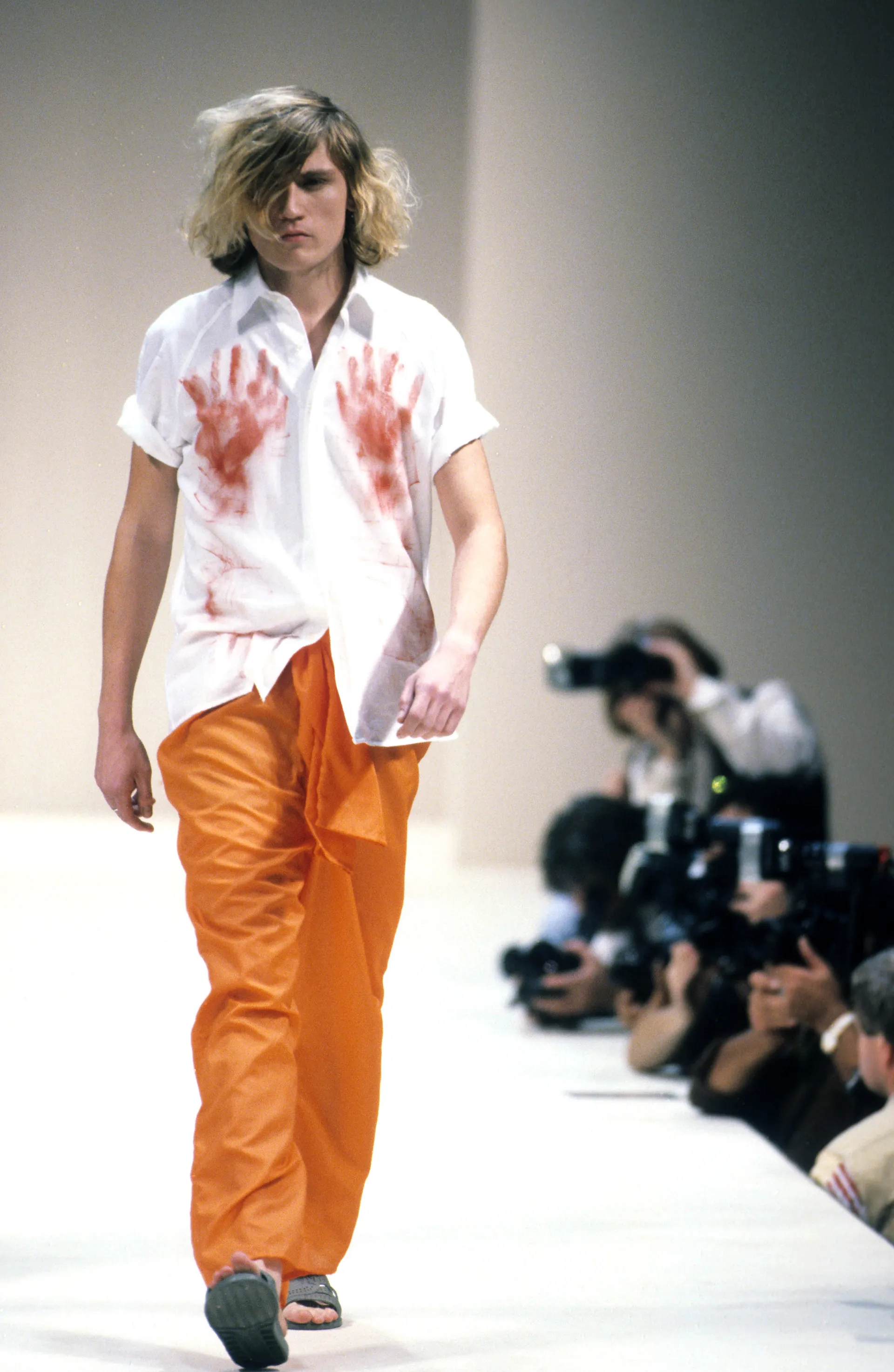

But what was McQueen's man like? The designer questioned classic gender norms with great subtlety: while his designs were always quite masculine, it was in the tailoring that the innovations were hidden. For the very first experiment in menswear, a line of twelve bespoke looks co-signed with H. Huntsman & Sons (described by the designer as the best tailors on Savile Row) were created suits described by Vogue in July 2002 as follows: «Narrow waists, wider lapels and [...] gold buttons and pink and yellow diamond tie pins and cufflinks». There was of course a more overt subversion, especially in the SS98 show which saw men wearing corsets and flip-flops with a small heel, but the sartorial representation of queerness was, indeed, in the tailoring and often flew under the radar. Looking at McQueen's men's looks today, the structural and semantic complexity of their construction is only partly perceived - the suits only look like suits and one struggles to make out, underneath the jackets, the cardigans subtly covered in sequins, the leather welt covering the hem of a jumper, the functional but strangely low waist for a traditionally masculine trouser, the fur decorating the sleeves and collar of a man's coat.

During an online Q&A twenty years ago, in 2003, and published on SHOWstudio, he was pointed out that menswear was taking on the same variety, colour and style as womanswear and, when asked about his ideal male image, he replied: «Menswear is I think fundamentally designed by men themselves. It's the hardest part of any house to design, because it's such a resistant audience. Men don't like being dictated to like women». And so the ambiguities and nuances of queerness were incorporated and dissimulated in the longilinear structure of suits, in the narrow shoulders, in the way the construction of jackets and trousers accentuated the curve of the back and glute msucles, in the way seams, pockets and structural elements focused their attention on the pelvic region of men, in the pagoda shoulders of certain suits that emphasised the profile of the trapezius muscles - «constellations of contradictory themes» which Icon explained well, many years ago, in an interesting in-depth study called Kinky Suits that shows how much technique was hidden in McQueen's work.

Seen today, those looks do not really seem to represent non-binary as we think of it today. More than a discourse on dressing conventions, however, McQueen used to narrate himself, his impressions and tastes through his menswear. In Alexander McQueen: The Life and the Legacy, Judith Watt notes that while early experiments in menswear up to 2002 were produced with an ideal customer in mind, from 2005 onwards McQueen designed with his personal taste as an ideal reference. As Keri Rowe writes in her essay Elevating the Other dedicated to the designer's SS06 'Killa' collection: «Having spent much of his career defending the strength of women in his collections, it is fitting that in approaching menswear, he would defend his own vulnerabilities. McQueen often stated that his collections directly referenced his own life». Certain elements recur frequently: the formal suit, the transparent top, the sleeveless knit, the corset, the baroque embroidery. But if this culturally omnivorous sense of decorativism reflected McQueen's artistic passions and obsessions, the real revolution took place in the minutiae of construction - just as in the case of the current King Charles III's jacket, the designer's message was deeply concealed in the structure of the clothes, one could perhaps sense it but not clearly discern it. In the 1990s, Karl Laferfeld said in an interview that McQueen's fashion sense was «nearer to Damien Hirst than to Givenchy» referring to the British designer's turbulent tenure as head of the brand's creative direction.

As mentioned, however, much of this vast menswear heritage has now been, if not forgotten, at least overshadowed by the magnitude of the spectacle brought to the catwalk by the women's collections. Soon after McQueen's death, Sarah Burton composed a collection inspired by historical English costumes that still bore a trace of the aesthetic to which the designer had accustomed the public. But the desire to shock was gone, as was that sense of shameless irreverence that, in the aftermath of the acquisition of the Gucci Group (which would later become Kering), led him to respond to those who wondered if he would become more commercial: «It's never become more commercial; it's always been the same. Nothing affects me». Of course, McQueen himself believed in mixing high and low, after all it was he who launched McQ, the brand's diffusion line that still exists today. Nevertheless, it is not hard to believe that a designer so opposed to the establishment and the hypocrisy of marketing would have reacted to the hyper-commercialisation of his menswear and his brand, which, by the way, also ended up producing Kate Middleton's famous wedding dress for the British royal wedding - just think that in his lifetime McQueen, a Scotsman for whom England had literally raped his homeland, had turned down a formal invitation from the Queen of England to a state dinner with the Emperor of Japan. A classic case of «You either die a hero or live long enough to see yourself become the villain».