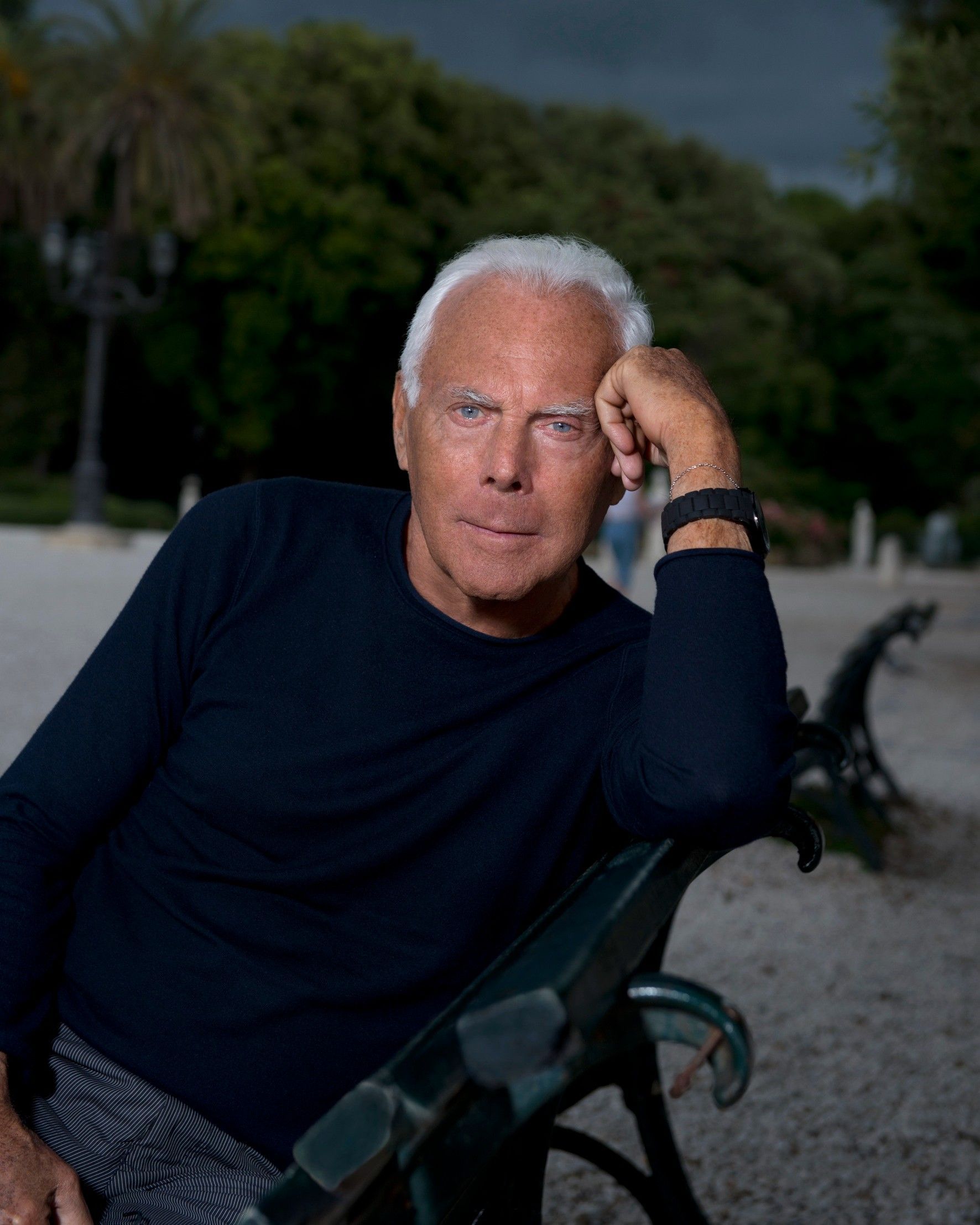

Is Armani right in saying that fashion today lacks substance? «Everything is very, very superficial», the designer said to the Financial Times

The massive machine of the fashion system is creaking. In the last twenty-four hours, two different articles in two different newspapers have lamented the sterility that is plaguing an increasingly aseptic, robotic, and risk-averse fashion industry. One is The Fashion World Has a Talent Problem, written by Cathy Horyn in The Cut, the other is an interview by Silvia Sciorilli Borelli with Giorgio Armani for the Financial Times. In both pieces, the journalist and the designer express similar points of view, criticizing the gentrification of an industry that, at least in theory, produced its best cultural results when its ecosystem existed in its natural state, so to speak, and not under the current form of intensive breeding. In particular, Armani has been critical of large conglomerates such as LVMH and Kering: «These French groups want to do everything, I don’t get it . . . it’s a bit ridiculous. Why should I be dominated by one of these mega-structures that lack personality?» Adding that producing fashion is «very hard nowadays because what young people like today, they won’t like tomorrow . . . and this underworld of [VIPs] set trends, there’s a lack of culture, of substance».

A feeling shared by many, to be honest, as also demonstrated by Horyn's article in which Sydney Toledano himself, one of the industry's highest-ranking big shots, at whose feet LVMH's Fashion Division stretches in all its vastness, says: «I’m not in nostalgia. Because if you are nostalgic, you will be frustrated. [In Galliano's times] Dior was a small company; we could talk every day and fix problems as they arose. And we had the mentality of the artisan. But the need today might be different». A thought that has assailed many this week, which has seen up-and-coming designer Peter Do present a bland collection for Helmut Lang's revamp, no doubt at the behest of Fast Retailing's apprehensive managers, and Sarah Burton leave Alexander McQueen, a brand whose founder was one of fashion's greatest geniuses and whose vision has been freeze-dried and reduced to a few meager exterior components, a synthetic formula that has never seemed as alive and pulsating as the savage beauty that Lee McQueen has brought to the catwalk for years. With sublime and ferocious irony, Louis Pisano wrote on Twitter that Burton's most enduring contribution to fashion was those Oversized trainers, which, however, are arguably the flagship product in the brand's financial reports (which are never published in detail). A symbol, if you like, of the paradox whereby, on the one hand, fashion culture, turned into an industry, has transformed an artistic heritage into a commercial phenomenon, on the other hand, that same commercial success has allowed the brand to outlive its founder. Assuming this is a good thing.

fashion by nature is elitist, them spending money on pretty popular people to wear their clothes isn’t alienating people who can’t access it, it’s creating more desire. Also access to fashion isn’t a human right…. https://t.co/VwV5mjLR02

— LOUIS (@LouisPisano) September 12, 2023

According to Armani, luxury groups lack personality - which is true since every brand now produces every single product category to penetrate every stratum of the market. Armani also says he took a picture with an older lady who «was probably never able to afford any of my designs in her life, and she cried». But today, anyone who cannot buy a couture dress like the lady in question can always buy a foundation, a logo t-shirt from some diffusion line, a trainer, and, in the case of Armani, even a piece of furniture. There are a thousand doors to enter the system, some smaller and humbler than others perhaps, but the only real barrier is price. And rightly so: wearing luxury goods (Horyn, following Eugene Rabkin, makes a dutiful distinction between luxury and fashion) is not a natural and inalienable right, the fashion system feeds on exclusivity and, to quote Pisano's tweets again, «people want brands to focus more on art and not making money but then get upset when brands shutter and designers get sacked because there’s no money - when they’re not even buying anything from said brands to begin with». It is therefore obvious that, with profits in mind, these big houses turned billionaire behemoths work with the same mentality as Zara: churn out new products, keep customers coming back to the shop, offer them everything they could possibly want, from evening gowns to ping-pong paddles, from mascara to upholstery. Paradoxically, the strategy works as Inditex has seen its sales increase by 16.6% in the first half of 2023 and even plans to raise prices, effectively imitating the luxury industry. Strangely enough, and readers may pass the term on to us, luxury is being 'zarified' while Zara is being 'luxified'.

@fashionxrhiannon The best Prada loafer dupe I have ever seen #pradaloaferdupes #loaferstyles #outfitstyleinspo #loaferoutfitidea original sound - fashionxrhiannon

«The thing is that today’s designers draw inspiration from the past and it’s not like they are inventing anything unless they do a mattana [something crazy, i.e.]», continued Armani, echoing the disenchantment that hovers in the corridors and antechambers of industry, where half-voiced insiders conclude each reflection on the creative fatigue of the system with a philosophical: «But it's all been done, we've already seen it all». And indeed, how often can one reinvent a sweatshirt, a blazer, or a skirt? This also reflects the new requirements of creative directors, fewer designers and more curators, aggregators of pre-existing signifiers, recyclers if you like, and playlist composers. Curiously, the greatest innovator of the last ten years, Virgil Abloh, also claimed that it was enough to alter an existing design by 3% to make something completely new out of it. In effect, it creates a shift in values: from the efficient excellence of the past to the excellent efficiency of today. But what happens when the engine of this car loses efficiency? Recently Bernard Arnault spent €215 million to buy shares in LVMH, whose value dropped by 14% after a financial report showed weakening sales in the key markets of the US and China. At this level of magnitude, strangely enough, the slightest cough from the giant sows agitation and terror in investors, an anonymous and endless mass that inevitably dilutes the leadership of any company that has to bow to it.

Perhaps then there is hope for degrowth, if not as happy as the one dreamt of by Professor Latouche, at least capable of bringing an industry that has become so large as to ballast itself to its senses.