Fashion wants to be different but is not willing to change In search of a new world

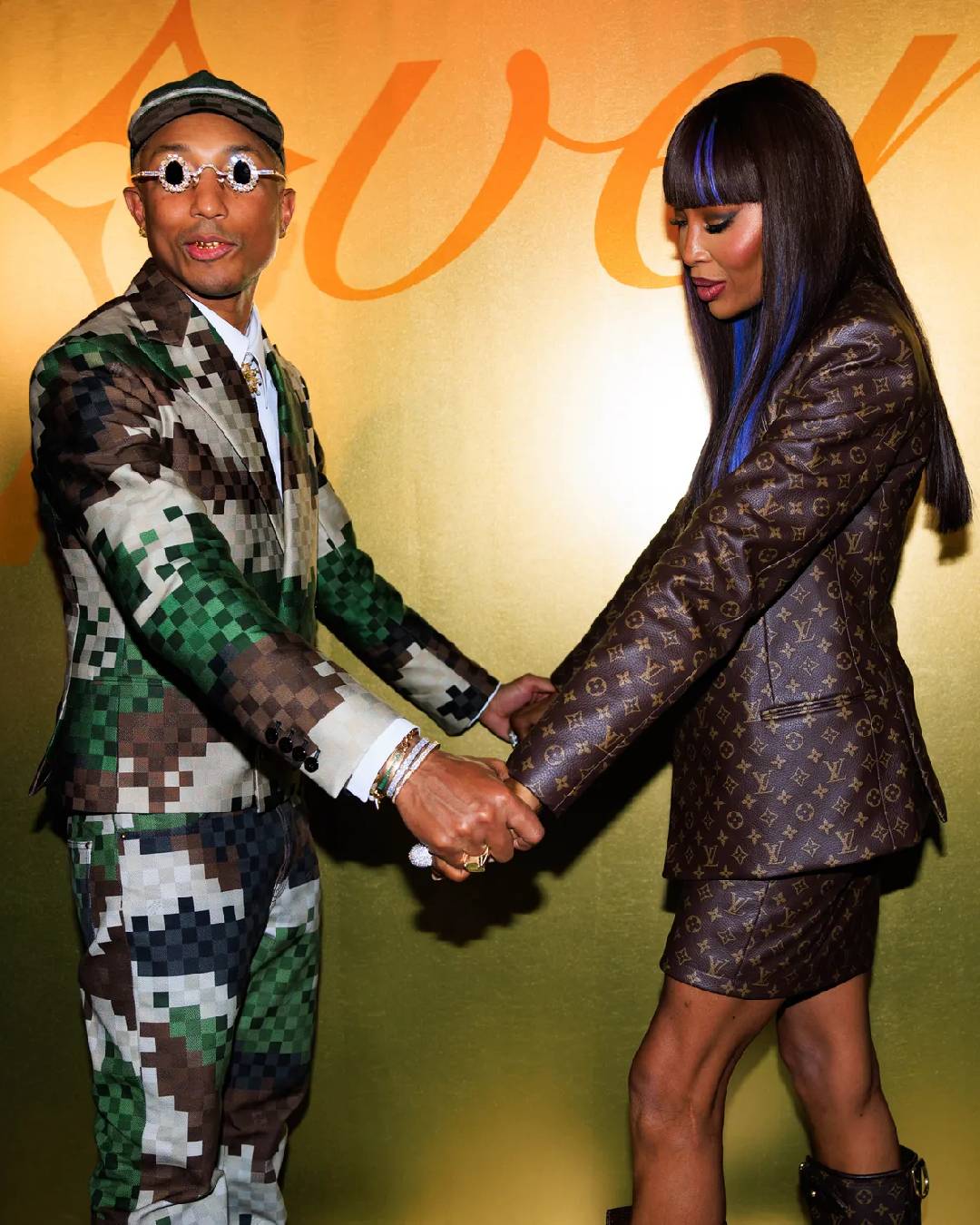

The pandemic, long since over, had challenged the business model on which the fashion industry is still based, seemingly leaving room for change. But today, after three years of debate, the answer to the question "what has changed?" is glacial: nothing. On the contrary, the shuffling of creative chairs at the top of the major groups has helped to exacerbate the confusion that dominates the industry, resorting to hype in the case of people like Pharrell Williams at Louis Vuitton or Future at Lanvin, and playing it safe with established professionals in the case of Sabato de Sarno at Gucci or Stefano Gallici at Ann Demuelemeester. There are no more certainties, it's not clear what the right strategy is to run a machine that requires more and more money, time and abandonment. And yet we all continue to use processes and methods that originated over forty years ago, when pens replaced fingers to write and tell stories, and when fashion shows perhaps really made sense because they were the only way to communicate with one's audience through the press. We change never to change.

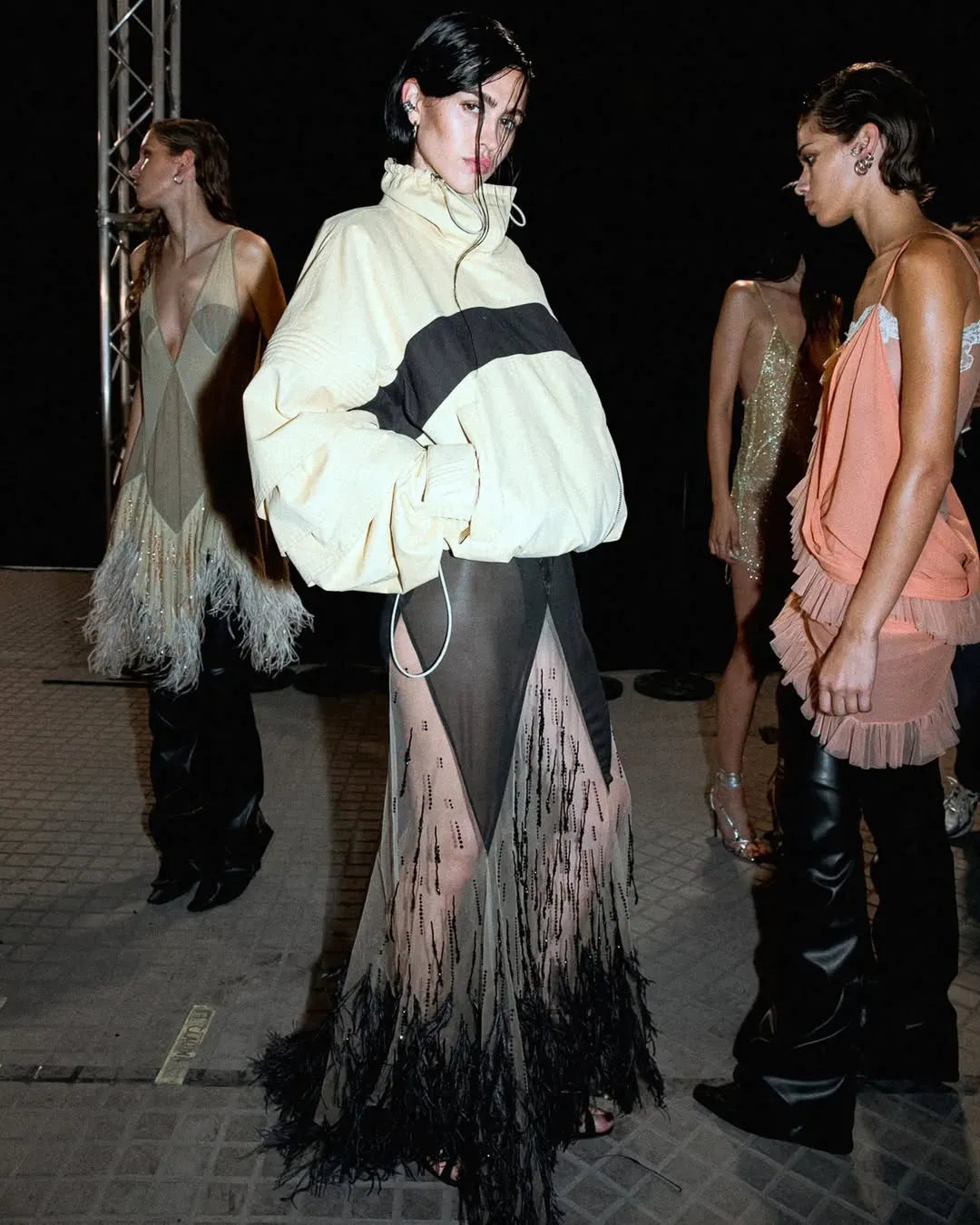

We are all aware that rather than living, fashion today, pursuing a business model based on the quest for ever higher sales, survives, waiting for a sort of universal judgement, the child of the contradiction between the apparent values of the new generations and the demonic allure of fast fashion. Although we are all aware of this, when asked why we continue to do shows, the answer is as tired as it is honest: it is the only thing we know how to do. Fear, laziness and selfishness drive the decision-makers, who are usually too old to understand the needs and wills of a world trying to be new and ferrying creativity towards stale business models. Magliano's triumph and Setchu's success are somewhat reminiscent of Italy's victory at the European Football Championship in 2021: that weak and reassuring illusion that things are changing when everything is standing still, because the real problem is not the lack of creativity, but rather the framework in which that creativity operates. We have seen so many promising designers sucked into a system that prefers them to be profitable rather than brilliant, lost in a labyrinth of showrooms, PR, buyers and shows that push inventiveness aside in favour of sales. And so originally successful brands are extinguished by becoming part of an old, hierarchical, closed and ego-based system, whereas sometimes it would be enough to choose a direct-to-consumer model to save time and costs and, above all, to maintain the magic and direct link with consumers without a superstructure that erases their uniqueness.

The change we all hope for certainly comes through the search for new creatives and contexts in which to bring them to life, but it becomes even more fundamental for brands to cut their bridges with the habits of the past and build a healthy and real community, where there is a dual relationship and exchange. The era of exclusive fashion that looks at its consumer with detachment is over and no longer captures the attention of the new generations who prefer to take refuge in vintage, escape from the present through nostalgia, or support independent brands with which they share aesthetics and values. The need for change is obvious, but the fear of losing one's privilege takes over everything else and so we risk rotting anchored to an old world based on barriers and boundaries. So it becomes legitimate to ask what sense it makes for an entire sector to struggle to survive when different choices could make it flourish. To the new generations the arduous judgement and the challenge to pave the way to a new world, perhaps a truer one, hopefully a better one.