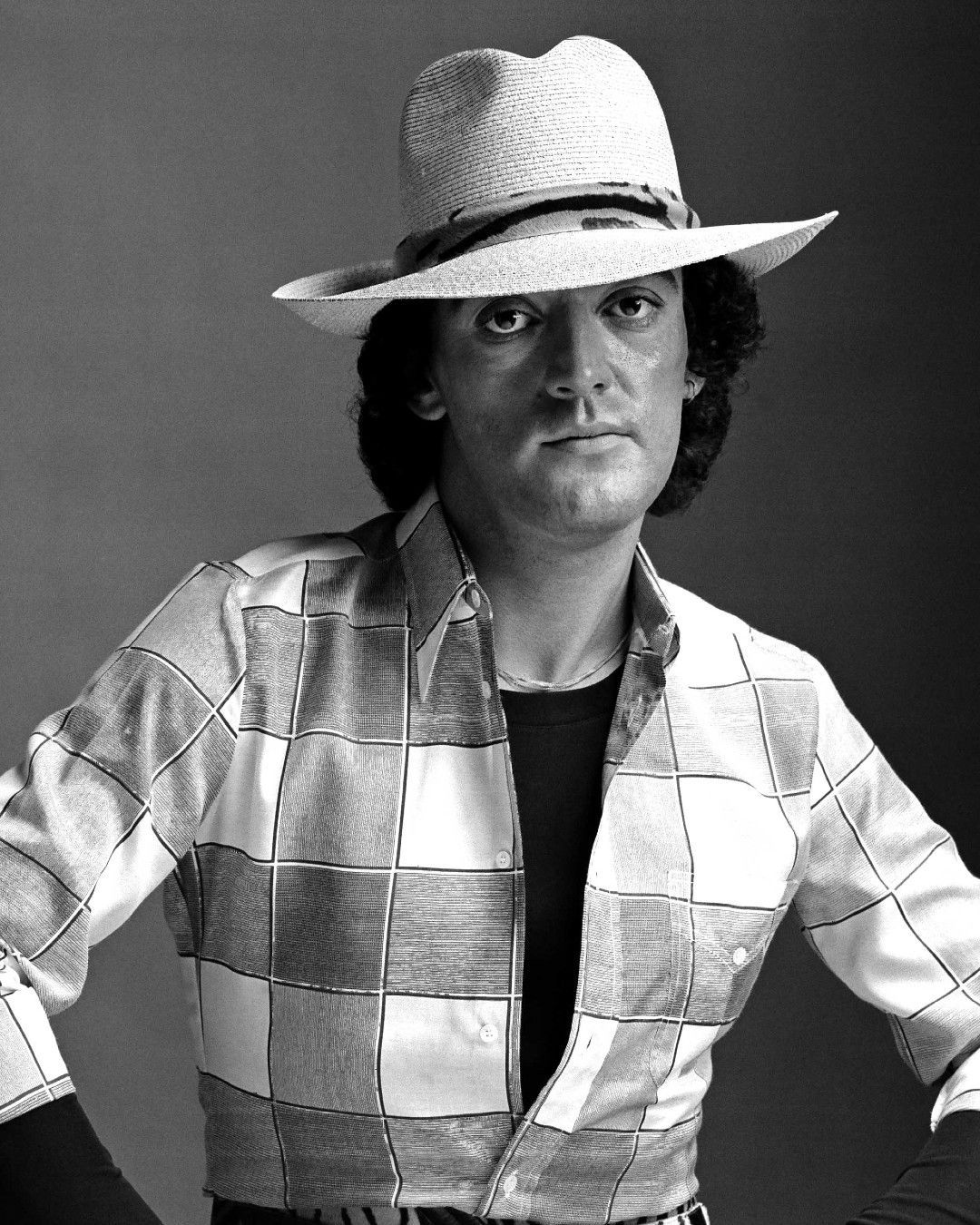

Walter Albini and the issue of "fashion revivals" Is it better to have an old brand or a new designer?

The Italian fashion world has enthusiastically welcomed the news of the Walter Albini revival announced last May 9. On the one hand, there is the obvious opportunity to rediscover the work and importance of a revolutionary designer thanks in part to the collaboration of archivists and brand experts; on the other, one wonders what will happen when such an appreciated and celebrated creative legacy has to bend to the inescapable laws of marketing in order to sell. We are, of course, in the realm of pure speculation, not meant to discredit but, as they say in America, «hope for the best, prepare for the worst». From the earliest communications, however, those behind the revival have made it clear that respect for the archives will be utmost and that this is (we take the term) speculation with heart. Indeed, the personalities involved are a guarantee of authenticity: the major investor Rachid Mohamed Rachid is the current CEO of Mayhoola for Investments and the chairman of Valentino and Balmain, the consultants are all people close to Albini's work, and so the philological value of the operation should remain intact. All the more so if Alessandro Michele really were to become the brand's creative director as many say. But, Michele's presence aside, as pointed out by Fabiana Giacomotti of Il Foglio, these revivals have some entrepreneurial disadvantages since they require investment in the restoration of brand awareness and run the risk of being made to rag on by the press, pundits and purists at the first misstep. To this we might add a third risk, which is that of following the archive too slavishly by questioning the very modernity of the operation. But with any hope, and given the caliber of archivists and consultants involved, the Walter Albini revival will focus more on repurposing an approach and a point of view than on passively reproducing an archive from over thirty years ago. Indeed, as specified by Rachid himself, forming a team of the right caliber to lead the brand is the number one challenge at the moment. In general, however, it must be said that in fashion for every successful revival (see Schiapparelli) there are ten that could have been avoided.

When bringing a defunct brand back to life (the craze for polite euphemisms that are now the rule would dictate the use of the adjective "sleeping") a reinvention is always necessary and therefore, in the absence of the original designer, and in a completely different historical and commercial context, that of the founder is likely to remain just a name on the door, an intellectual property, the mask disguising the identity of another designer altogether. But then why not cut the middleman and try to fund the work of creatives with their own brand and name? The history of the last decade, for example, tells us that launching a brand from scratch may take longer to create a reliable heritage, but it leads to the most solid successes: the big names of European luxury, for example, are now joined by the relatively young The Row; in recent years, then, the intrinsic sense of novelty brought by Jacquemus to the industry has attracted droves of fans, the same could be said of Peter Do, ERL, Nensi Dojaka, Heliot Emil, and Marine Serre, to name a few. But even the new brand of an already celebrated designer like Phoebe Philo is generating huge levels of anticipation without being the revival of anything, even if tied to the obvious nostalgia for the "old" Céline. In a rather strange case then, the excellent duo behind GmbH achieved great results with their own independent brand but struggled with a heritage as heavy and difficult as Trussardi's, so the path marked out by the corporate handbook that many CEOs follow even too much to the letter did not prove effective. In fact, the existence of a long pre-revival heritage is both a great attraction and a hard limitation: the same pre-existing brand awareness that seduces investors often also represents a bias about what the brand can and cannot be on the part of the public. That bias can often prove fatal.

If only the cash injected in fashion revivals were spent on strengthening younger brands people actually care about and know.

— @PAM_BOY (@pam_boy) May 9, 2023

According to a BoF article from almost a decade ago, the appeal of revivals from an economic perspective is precisely about that pre-existing heritage, which is the first and indispensable ingredient of a brand that wants to position itself in luxury. Again the same BoF article, speaking of the Paul Poiret revival, wrote: «The fact that these brands are largely forgotten outside of expert circles, means that […] the investor who decides to revive the brand has significant creative room to manoeuver. In fact, [the] model depends on a degree of forgetfulness on the part of the consumer, who will ideally perceive the ‘revival’ of a brand». That is to say, once you get the rights, you can whatever you like with the designer's name. The model, however, did not work for Paul Poiret, who stopped posting on Instagram in 2019: it obviously did not make much sense for a Korean company and a Belgian businesswoman to employ a Chinese designer to bring back the name of a French couturier who retired in remote 1944 because other designers like Chanel had surpassed him in terms of innovation. In that case the operation was dead on arrival. The same can be said of Vionnet, which took one of the most celebrated names in the history of couture and used it to sign sneakers and fully forgettable dresses and ended up shutting down again in 2018 in an unapologetic and somewhat humiliating silence. The list could go on, especially with the difficult case of Halston - but the existence of so many failures does not prohibit a successful fashion revival from actually happening.

@fordmodels Ford Models at the @pucci show in Florence #FORDmodels #AmarAkway #AwarOdhiang #EvieHarris #QisiFeng #Steinberg #Pucci #InitialsEP #Model #Runway som original - fordmodels

Two examples demonstrate how a possible way forward is through hyper-specialization: one is Moynat, owned by LVMH, which opted for a quiet relaunch in 2021 under the leadership of Nicholas Knightly; the other is Franzi 1864, a historic Milanese leather goods maker resurrected by Marco Calzoni and Stefan Oelze. Both of these brands are working on a single category, the very high-end handbags, proceeding with great caution, establishing a language based on a distinctive and recognizable product without unnecessary fuss. Getting to huge sales volumes will take time, of course, but what matters is that the product is credible. Things get more complicated, however, when you have to move out of the single merchandise category and into the full look. Pucci's recent revival, for example, has been fairly faithful to the archives and follows a prudent policy that does not want to juxtapose it with other industry giants-no less, at times when the brand breaks away from the original prints and wide silk chiffon garments, it begins to falter. Do the brand's archives have enough creative gasoline to fuel years and years of collections? Elsewhere, however, Courregès's platform has been great for bringing Nicholas di Felice's talents to the fore even if the original designer's name is now associated with basic logoed garments with pronounced collars and a workwear vibe-all things for which the use of Courregés's name is somewhat superfluous. But so what to choose between an old brand and a new designer? Karl Lagerfeld, who once provoked a journalist by telling him that after his death they should throw away all his archives, was a fan of "new is always better" and once said: «There is nothing worse than bringing up the 'good old days.' To me, that's the ultimate acknowledgment of failure».