Why we need more female designers A short eulogy to women in fashion

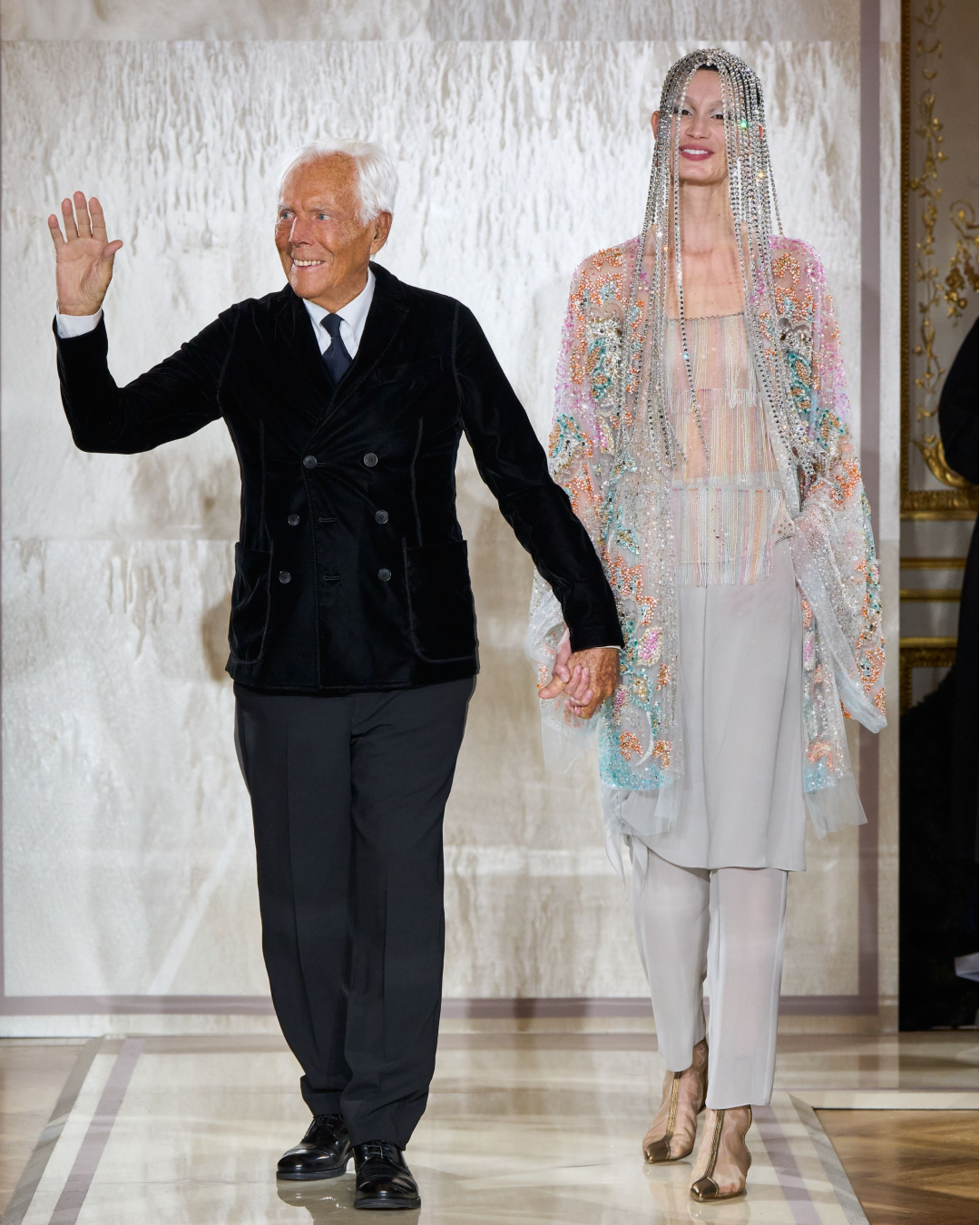

The fashion world shows that there is room for everyone, from Giorgio Armani to Martine Rose, from Maximilian Davis to Maria Grazia Chiuri, but women's climb to success in the fashion industry appears to be still more difficult than that of men. A recent study by EUIPO shows that in Italy only 25% of designers are women - a gender gap that, according to the current growth rate, would take longer than 50 years to close - and that in Europe, female designers have an average salary 12.8% lower than their male counterpart. According to the stereotype of The Devil Wears Prada, Sex And The City and even Cruella Demon, the fashion world revolves around powerful and fierce women, but the truth of the matter seems to be quite different.

«You can really tell when a designer loves women» is one of the most popular phrases on Twitter during the fashion show months, and perhaps one of the truest. The level of refinement of a silhouette, the attention to detail, the preciousness of the elements woven into the fabric of a dress do not matter, if the finished product does not fulfil its ultimate purpose: to enhance the woman who wears it. For the August 2019 issue, British fashion journalist Sarah Mower dedicated one of her Vogue features to the designers who are «reshaping the industry, not by conforming to male rules but by constantly ignoring them, trusting their instincts, living as they wish and opening up the creative space for an entire generation to flourish.» While it is true that designers like Gianni Versace and Azzedine Alaïa, both men, have in their time celebrated women's bodies in majestic ways, covering - and uncovering - the supermodels of the 1980s and 1990s in all the right places, the way designers like Miuccia Prada, Rei Kawakubo, Vivienne Westwood and Phoebe Philo have portrayed the female universe on the catwalk shows that inventing clothes is not just about glorifying a breast and a bum and enhancing them as much as possible, it can also be a way of telling a story. Historically, clothes serve to look good, to fulfil the laws that by nature entice humans to reproduction - simply put, for sex - but this does not always have to manifest itself in an exaggerated decolleté or a pair of vertiginously high heels; sometimes, to feel beautiful, confident and therefore seductive, a woman needs functional fashion, and these designers' clothes do just that. Think, for example, of Mary Kate and Ashley Olsen, the artistic directors of The Row: none of their collections has ever lacked sensuality, yet the models they send down the catwalk are almost always wrapped in kilometre-long swathes of fabric draped like the petals of a flower.

the row fw14 pic.twitter.com/rUsEyqLgS6

— lua (@anndemeuleprada) April 22, 2023

Wether female fashion designers work differently than men was a question that WWD asked the designers themselves. Mrs Prada explained that «being a woman has taught me to compromise in many situations, both personally and at work. This, for me, is a great achievement because from compromise, one can usually arrive at a greater result without necessarily giving up anything,» while Donna Karan avoided minced words, explaining that it all boils down to the sense of practicality that men lack, almost always stuck in their fantasies. «Fashion is often too young. Not everyone can wear a miniskirt, nor should they. We are not models. There is a reality. It is a basic reality.» To the practicality and compromise of Prada and Karan add concrete sophistication, and you have the Old Celine of Phoebe Philo, the quintessential «Woman Who Designs for Women» who now has more dedicated fanpages than any teen romcom actor. We will not repeat ourselves, and we will avoid reminding you how Philo has managed to perfectly portray through her designs that modern ideal of an emancipated woman, confident in her convictions, chic almost without being noticed - for that, there's this article. The record sales numbers that her garments continue to register on online resale sites, as well as the subculture that her disciples, the «Philophiles,» cultivate online as they fervently await their heroine's return to arms, are enough to prove that she, like few, has been able to interpret the needs of 21st century customers.

Leaving aside for a moment the current pay gap data - in 2021, women working in art, design, entertainment, sports and media earned 87 cents for every dollar earned by men - and adding to the list of designers already named others such as Jil Sander, Donatella Versace, Stella McCartney, Vera Wang - who wouldn't want to marry into Vera Wang? - Molly Goddard and Simone Rocha, the flourishing careers of these female designers confirm the thesis here exposed: we need more female designers, because only those who are part of the female universe can truly translate it into dress. It is as though there's a collective female consciousness that is only translatable to those who are part of it: in the 1960s, Mary Quant had picked up on one of the signals by bringing miniskirts to the catwalk, in the 1970s Vivienne Westwood had offered neo-romantic Punk, and in the 1990s Donna Karan and Miuccia Prada had given women back the chance to dress sexy for themselves, not for men as 1980s fashion wanted. Each of these designers was able to grasp like no other - although Yves Saint Laurent came close, with «le smoking» and all - the needs shared by women of the time. Beyond artistic innovation and the promotion of inclusiveness among the younger generation, mentioned by Mower in Vogue and by all those who, as is right, stress the importance of gender equality in the workplace, this plea for greater female representation at the top of the artistic direction of fashion houses is, to quote another Twitter cult phrase, «for the girls, the gays, and the theys,» that's it, because only them can really know what they want to wear.