What is rapwashing? This year's unusual rap turnout at Sanremo Festival

The world of hip-hop culture, and in particular rap as its most widespread and successful expression, has always been the subject of great debate. Since its large-scale diffusion, there has been endless debate or solution as to what is or is not true rap, what ideals it puts forward, how it relates to violence, poverty, social injustice, wealth disparity, illegality, what are its aesthetics, how far it is or is not allowed to be mainstream and to contaminate itself with other genres and styles. Opinions may be more or less extremist, but what emerges from objective analysis is ultimately not consoling for genre purists.

Gli articolo 31 sono il rap zarro con cui sono cresciuta negli anni 2000 che poi tutto a un tratto si lasciano e ritornano a cantare insieme anni dopo a sanremo ammettendo le loro colpe e dichiarandosi amore fraterno

— mic (@qwasisenzatesta) February 11, 2023

Me li immagino così i one direction tra dieci anni#Sanremo2023

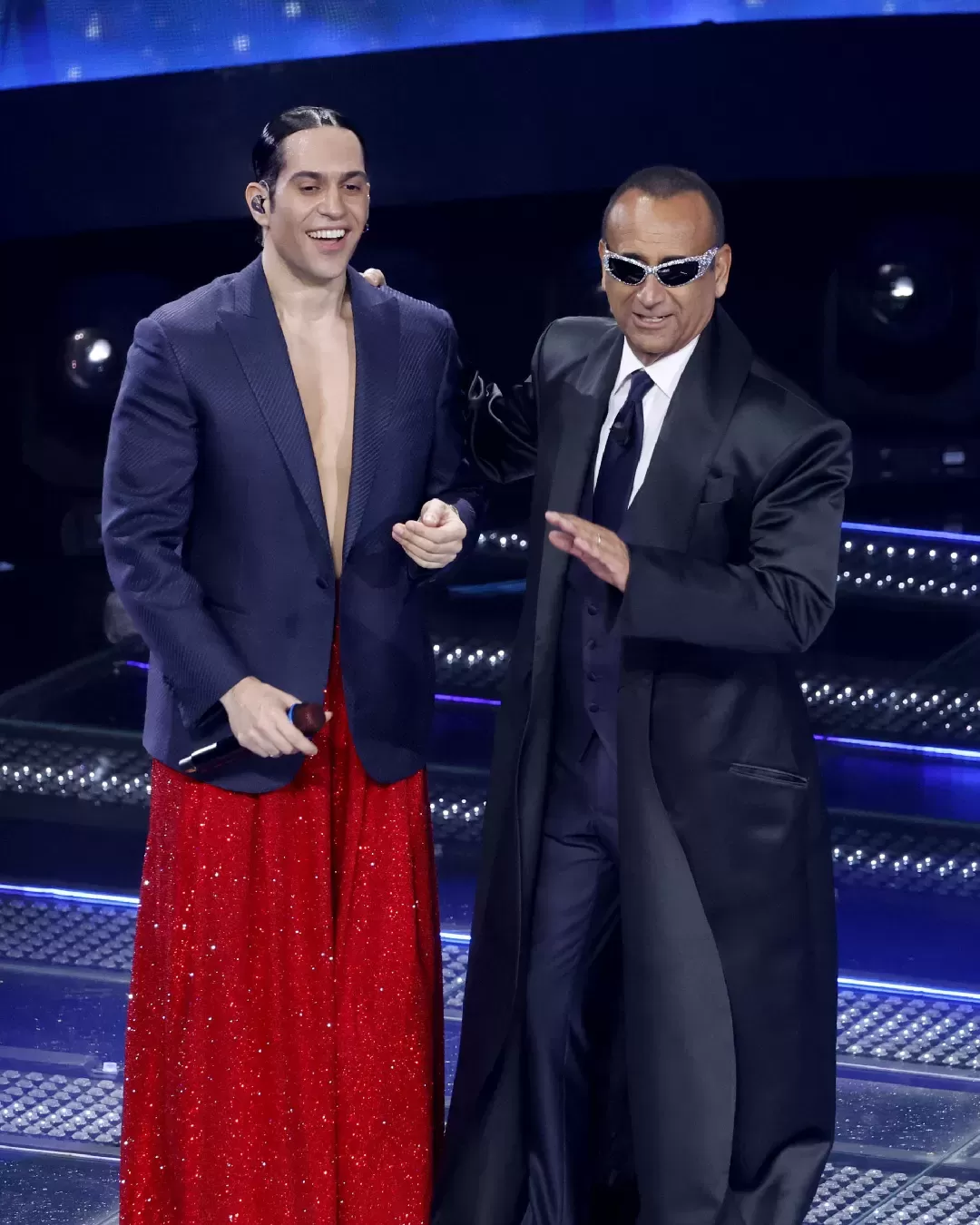

It seems impossible for rap music to escape the big mainstream and commercialization machine, although according to Guè, for example, resistance still exists. In Italy, as everywhere else, there is a growing feeling that rap has completely abandoned its origins and socio-cultural specificities to become a musical genre like any other, sellable and performable everywhere and by anyone on par with pop music, as all it takes is the right look. After all, the same process, only a hundred times faster, has also recently happened to trap, as UFTP began to explain very well in "Trap - Dystopian Stories of an Absent Future" for Agency X. This is not to say that discussions have died down in the face of this overwhelming realization, but quite the contrary: the Sanremo Festival reignited them. At a superficial glance, last year several artists of the rap sphere have performed on the prestigious Ariston stage, as contestants and guests. Madame, Izi, Lazza, Salmo, Fedez, Gue Pequeno, Big Mama, Articolo 31. Between old and new rap generations, in a commonality of hearts ideally appreciated by anyone who has approached Italian rap in the last 20 years. Lazza, with his Cenere, has even managed to come second, declaring among other things: «Hip hop has won». In the edition that is about to start next week, rappers are still on the rise: Geolier, Ghali, La Sad, Mr. Rain, Rose Villain, Tedua, Il Tre, and these are just the main ones among those we will see, guests and contestants, on our television screen this year. A revival of the genre? It doesn't look like it.

It was precisely on this statement that some of the Italian press focused, and a debate ensued (or was reborn) on the forms of "mainstream" rap, on what it means to bring hip hop to a stage that nevertheless remains traditionalist, and on what one is willing to sacrifice in order to do so. Rockol, for example, didn't mince words. According to Claudio Cabona, what we saw on Rai 1 was anything but hip-hop, in contamination with pop and with the category that could be defined as "of Sanremo", which was not appreciated. In the same vein, Soundwall spoke of rapwashing, a term that takes its cue from pinkwashing and greenwashing, using the term for the first time, at least in Italy. In general, it seems that, in last year's edition, Fedez's freestyle on the cruise ship and Big Mama's performance with Elodie on the notes of American Woman were appreciated. Not liked instead was Izi's choice to perform, with Madame, Fabrizio De André's Via del Campo without adding anything of his own. Not even mentioned, then, was Sangiovanni, in a cleaned-up-cosplay-version of Gianni Morandi as a young man. It is not hard to understand why he was not mentioned, after all, he comes straight from the school of Maria De Filippi's Amici, but it is impossible not to notice the decisive turn in music and image, probably a harbinger of a deeper change in Sangio's character.

Soundwall speaks of rapwashing in an even more subtle way than is commonly understood when speaking of "washing", arguing that rap has been used by the Sanremo Festival to make headlines, to make itself look young, talked about and that in the process it has been contaminated, undersold, filed down and emptied, especially in terms of themes, vocabulary, and messages. There is truth in this: such a communion of hearts between an event of this caliber and Italian rap would have been unthinkable only a few years ago. Fabri Fibra knew this very well. His Andiamo a Sanremo, dating back to 2007, should guarantee him, due to the rawness of the lyrics and the names and surnames given, at least another five or six years away from the city of flowers. Rapwashing, however, transcends the festival itself to spread like wildfire across all fields of mainstream entertainment. In recent years, in fact, the world of Italian entertainment, with television in the front row, has decided to cash in on the destructive aura of rap, swallowed and rehashed, ridden, and then shot down. Again, the parable of Sangiovanni comes to mind.

Rap, however, even if its origins say otherwise, is no longer considered a social issue. Not in the last thirty years, and not in Italy. The Sanremo Festival, then, is an engulfing monster by nature, as is any fame and sales mechanism of that size. If rapwashing does exist and granted that it can be linked to greenwashing and pinkwashing practices, definitely pre-dating February 2023, it is attributable to the extreme fluidity of the music industry and the way it has been changed by social networks, the virality mechanism, and the change in the listening habits of younger generations. Part of the responsibility, then, can perhaps also be attributed to the natural tension to change, to adapt to a market, namely the music market, that is always on the move and in close dependence on the tastes of the public and, finally, to the nature of the genre, so rooted in its time that cannot last forever without changing. Whether one likes it or not. Lazza himself admitted in 2021 that he did not want to rap forever.